You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

15+ Years of US's Proxy Occupation of Haiti: US Sponsored Coup d’Etat. The Destabilization of Haiti

- Thread starter loyola llothta

- Start date

More options

Who Replied?loyola llothta

☭☭☭

1st U.S Occupation of Haiti (1915)

Here is when Haiti military went from history of glory to the most disgraceful group of men in north América

salute the real zoes

This July 28 marks the 104th anniversary of the US occupation of Haiti (1915-1934). Posterity must remember the Resistance fighters who fought the occupiers and fell as Heroes for # Haiti: Pierre Sully, Charlemagne Péralte, Benoît Batraville and Rosalvo Bobo. # 28Jul

loyola llothta

☭☭☭

How did #Haiti become a client-state?

OTD: July 28, 1915, US Marines invaded and occupied for 19 years, looted the treasury, changed constitution, destroyed the original army to establish a subservient force trained and controlled by US Marines...The #shythole legacy continues.

loyola llothta

☭☭☭

The 19 yrs occupation was made possible by election theft, and the slaughter of 50,000 peasants. State Dept article admits they stole 1914 election. Also admits occupation gave wealth to the neocolonial settler class and left the remaining in poverty. See my pinned tweet. #Haiti

loyola llothta

☭☭☭

The US established a neocolonial army during the 1915-1934 occupation that terrorized the poor in #Haiti until it was disbanded in 1995. It's been replaced with UN "peacekeepers," the national police, and secret paramilitary death squads that continue to massacre with impunity.

https://twitter.com/intent/like?tweet_id=1155572809030127617

loyola llothta

☭☭☭

By decree, I will raise to the rank of Heroes of the Nation the patriots and resistant to the American occupation of 1915, Charlemagne Péralte, Rosalvo Bobo, Benedict Batraville & Pierre Sully, died as a martyr for the Republic, defending the national sovereignty

7:29 AM - Mar 10, 2019

Last edited:

loyola llothta

☭☭☭

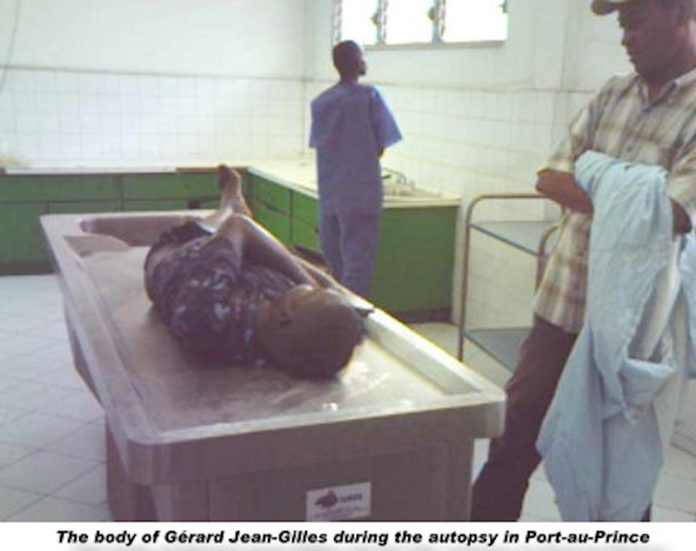

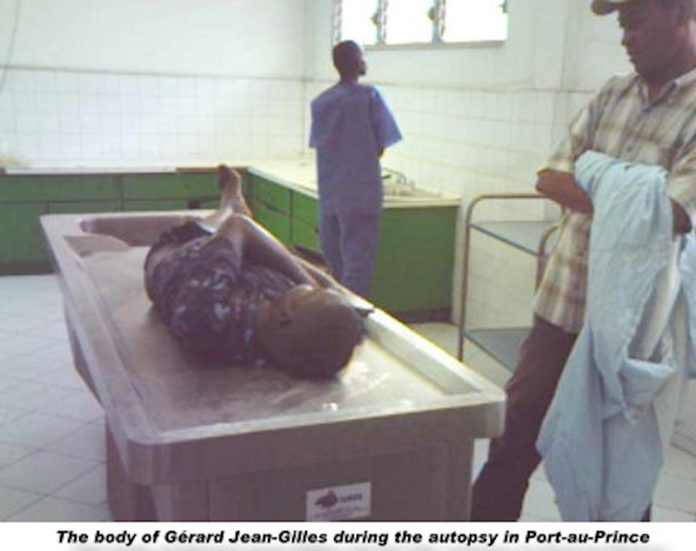

The Death of Gérard Jean-Gilles: How the UN Stonewalled Haitian Justice

September 21, 2011

Faced with growing outrage over an alleged sexual assault by UN occupation soldiers on 18-year-old Johnny Jean in the southern town of Port Salut, the UN is pledging to investigate the incident and bring the perpetrators to justice.

But this promise is belied by the UN mission’s refusal to cooperate with the Haitian justice system’s attempt to investigate the hanging death of a 16-year-old boy inside another UN base one year ago.

Link:

The Death of Gérard Jean-Gilles: How the UN Stonewalled Haitian Justice | Haiti Liberte

September 21, 2011

Faced with growing outrage over an alleged sexual assault by UN occupation soldiers on 18-year-old Johnny Jean in the southern town of Port Salut, the UN is pledging to investigate the incident and bring the perpetrators to justice.

But this promise is belied by the UN mission’s refusal to cooperate with the Haitian justice system’s attempt to investigate the hanging death of a 16-year-old boy inside another UN base one year ago.

Gérard Jean-Gilles ran errands for Nepalese soldiers at their base in Cap Haïtien, Haiti’s second largest city. A Haitian interpreter for the troops, Joëlle Rozéfort, accused Jean-Gilles of stealing $200 from her car. The next day, on Aug. 18, 2010, Jean-Gilles was found hanging from a tree inside the base, a wire around his neck.

The UN Stabilization Mission to Haiti (MINUSTAH) said its internal inquiry found that Jean-Gilles committed suicide. But Jean-Gilles’ family and friends suspect he was murdered, and when a Haitian judge tried to investigate, the UN stone-walled.

The former delegate (or central government representative) of Haiti’s northern region calls the UN “the primary obstacle” to learning how Jean-Gilles died.

In impassioned demonstrations against MINUSTAH this week, Haitians are calling for justice for Gérard Jean-Gilles, too.

“He died searching for a way to live,” said his adoptive father, Rémy Raphaël, whose street merchant wife took in Jean-Gilles as a baby, after his mother died and father went missing.

“He was in school, but my wife couldn’t keep paying for it,” said Raphaël, in the family’s sparse two-room home in a narrow, grimy alleyway. “He never tried to make trouble with people because he understood his situation, he preferred to search for jobs… That’s why he became friends with the soldiers.”

Evens Bele, 17, worked alongside Jean-Gilles on the MINUSTAH base for three years. They earned the equivalent of $10 a month, running errands, cleaning base facilities, and translating for the UN troops during patrols.

“He entered, said hello to me, and told me he had trouble with a lady who lost around $200,” said Bele of the fateful morning. Not long after, “I saw him hung up.”

UN personnel immediately met with the family and local officials. The body was flown to Port-au-Prince, Haiti’s capital city, the same day. But it sat for three days until Haitian doctors carried out an autopsy at the General Hospital, according to Calixte James, Jean-Gilles’ uncle, who accompanied the body.

“They could have done the autopsy the same day because we arrived in Port-au-Prince at 3:45 p.m.,” said James, a heavyset Blackberry-toting lawyer. “In our country, we don’t have the equipment that can detect things in [an autopsy on] a body after 72 hours. So to me what they were doing was already meaningless.”

An autopsy report obtained by Haiti Liberte said no traces of violence were found on the corpse, which the UN uses to buttress its claim of suicide.

But Raphaël, who worked as a dishwasher in the base, believes the UN soldiers “asphyxiated [his son] with gas and then hung him from the tree,” which was “in a restricted spot of the yard behind a lot of containers.”

“He could have fought them because he was strong enough,” Raphaël said, his voice rising. “He wouldn’t let them do that to him. . .To me the autopsy is not clear enough.”

The suspicions of Jean-Gilles’ family and friends swirl around interpreter Joëlle Rozéfort, who had accused Jean-Gilles of stealing money from her car the previous day.

The morning of the boy’s death, “Joëlle came to me while I was washing dishes, saying Gérard shouldn’t have stolen money from her,” Raphaël said. “While she was talking, a soldier came in and told me Gérard had hung himself! Her face stayed quiet… Even when Rozéfort found the money in her trunk, she kept on saying that Gérard was a thief.”

Bele also doesn’t believe Jean-Gilles committed suicide. “He’s dead because of the money,” he said. Shortly after the hanging, Bele and Raphaël both lost their jobs at the base.

The northern region’s former Government Delegate, Georgemain Prophète, represented the Haitian state in its initial dealings with the UN on how to probe Jean-Gilles’ death. They agreed the Haitian judiciary would open an investigation, he said.

The case was given to Heidi Fortuné, a Cap Haïtien investigating judge (juge d’instruction) since 2006.

“The autopsy can only show whether or not he was strangled, but it can’t determine if it was a suicide or if someone else hung him,” said Fortuné. “They sent me the case to investigate if it was a suicide or not – that’s my job.”

Witnesses said that Rozéfort “had a little trouble with her car and Gérard gave her some help,” Fortuné said. “After she started the car and left she realized the money in her bag was missing. She accused and made threatening remarks to Gérard, but Gérard said that he did not take the money. Rozefort promised him she’d report her allegation to the chief of the base,” he said.

Both Bele and Raphaël claimed in separate interviews that Rozéfort had a sexual relationship with the Nepalese chief of the base.

One witness who had seen Jean-Gilles enter the base that morning told Fortuné the boy had displayed no facial expressions or signs suggesting he would kill himself. Suicide is not considered part of Haitian culture and is practically unheard of in the island nation.

“So the next person I need to hear from is Rozéfort herself,” the judge explained.

Fortuné said he issued three separate subpoenas for Rozéfort to testify before him, the last of which mandated the police to arrest her and bring her to him. But MINUSTAH moved her to Port-au-Prince, saying she’d received death threats in Cap Haïtien.

Rozéfort never testified.

After issuing his warrants, Fortuné received a letter dated Sep. 16, 2010 and signed by Edmond Mulet, the former Guatemalan diplomat who headed MINUSTAH at the time. The letter was addressed to Haiti’s Foreign Minister, who sent it to Judge Fortuné.

“It is mentioned in the subpoena that Madame Rozéfort is suspected of complicity in voluntary homicide,” Mulet wrote. “Mme Rozéfort will not be able to comply with the subpoena. . . barring a decision by the UN Secretary lifting her immunity.”

The Status of Forces of Agreement (SOFA) between the Haitian government and the UN provides MINUSTAH members with immunity from prosecution in Haiti under certain circumstances.

But Haiti’s then-Justice Minister, Paul Denis, responded to Mulet in a sharply-worded letter arguing that Rozéfort enjoys no immunity whatsoever.

“I believe it timely to ask you, Mr. Special Representative, to accord one minute of reflection on the definition of the expressions members of the MINUSTAH and contracting parties,” Denis wrote, bolding and underlining portions of the text for emphasis. The SOFA does not provide immunity for the UN’s Haitian contractors. “It seems to me that Madame Joëlle Rozéfort, of Haitian nationality, recruited here, translator by profession, is certainly a contracting party and not a member of MINUSTAH.”

Denis emphasized that the SOFA provides immunity for acts carried out by MINUSTAH personnel in the “exercise of their official functions”. Therefore, “The official and contractual function of Madame Rozéfort consists of translating statements, conversations and documents from one language to another. . . In acting as a translator, Madame Rozéfort cannot in any way be led to kill.”

In an Oct. 8, 2010 letter to Denis, Mulet shot back: “Madame Rozéfort was recruited by means of a letter of nomination issued by the United Nations Secretariat. . . [H]er employment will be governed by the terms of her nominating letter and the Regulations of United Nations personnel. She is consequently an official of the United Nations.”

Mulet did not respond to Denis’ second point, that immunity is only applicable in the exercise of “official functions.” Mulet concluded, “the Secretary General [Ban Ki-Moon] and the Special Representative of the Secretary General [Mulet] are for the moment… not in a position to come to a decision on the request for a court appearance based on a suspicion of complicity in voluntary homicide.”

“Immunities should not be used as a shield to prohibit investigations into potential criminal acts that, if proven, would be clearly outside of the ‘official capacity’ of UN staff members,” wrote Scott Sheeran, an expert on peacekeeping law at the University of Essex who has worked in the United Nations, in an email toHaïti Liberté after viewing the exchange of letters.

“This is particularly so where the UN has not assisted the host government and local law enforcement to reach a view on what occurred,” Sheeran wrote. “It is not a good faith interpretation of the law, and, more broadly, it is not consistent with the rule of law and human rights which the UN is meant to uphold.” Mulet appeared to be claiming an “overly broad interpretation” of a key aspect of the SOFA, he added.

That same month, Mulet argued in a speech to international partners that Haiti’s principal problem is “the absence of the rule of law.” He said Haitians have ceased to expect or demand justice from the Haitian state and that the country suffers from a dearth of competent legal professionals. His role, along with that of the international community, Mulet added, is “not to undermine Haitian sovereignty, but strengthen it. I am very conscious of this.”

Edmond Mulet is now Assistant Secretary-General for Peacekeeping Operations at UN headquarters in New York. A year later, he “doesn’t feel that there was a denial of justice” in the Jean-Gilles case, according to Michel Bonnardeaux, a public affairs officer from the UN’s Department of Peacekeeping Operations.

Former Justice Minister Denis could not be reached for comment.

“I received the copy of a letter signed by Edmond Mulet saying the madam has immunity,” Judge Fortuné said. “But I know she’s a Haitian contractor and only the UN soldiers have immunity. How can Rozéfort be enjoying this privilege as a local employee?”

Fortuné asked: “Did she complain to the chief or say something that could give a occasion to Jean-Gilles’ death?. . . I can’t say with conviction whether or not he was killed by the soldiers, but they don’t cooperate enough to help with the investigation – that’s what is bizarre.”

Judge Fortuné concluded, his voice hushed with disappointment: “The UN is blocking the Haitian justice system.”

Gilles’ family is indignant and angry. “MINUSTAH doesn’t respect the Haitian justice system,” Raphaël said. “They think they are the only force on the planet and they can do whatever they want. . .They’ve only brought us corruption. They are doing nothing good for the country.”

“We don’t have any justice because our leaders have sold out the country to foreigners,” said Calixte James, the uncle. “How can a judge call the woman to testify, and the UN refuses, saying she has immunity. She’s Haitian!. . . Gérard’s family is asking the whole world judge these things that MINUSTAH is doing in Haiti.”

Jimmy Jean, 18, lived with Gérard. “I want them to give him justice,” he said. “At night with some friends he used to sit with me joking until we went inside to go to bed. I cried. I cried a lot – he was my only brother so what’s wrong with it!”

Last October, protestors in Cap Haïtien fought pitched street battles – using rocks, bottles, and Molotov cocktails – with MINUSTAH troops, turning the town into a veritable warzone. Judge Fortuné said he was forced to round up his kids and dash out of his home when it was flooded with tear gas. The protesters blamed the Nepali UN troops (correctly, as scientific studies would later prove) for introducing cholera into Haiti. The resulting epidemic has now killed over 6,100 Haitians.

“MINUSTAH’s refusal to deliver the justice [in Jean-Gilles’ case] that the people demand, and the fact that a MINUSTAH battalion is pointed to as the source of the [cholera] epidemic,” said former delegate Prophète, “when you put all that together, it’s a very toxic compound and that can make anything happen.”

James and Judge Fortuné confirmed by phone this week that nothing has changed in the Jean-Gilles case since last year. They said the investigation could not progress without Rozéfort’s participation.

“I am absolutely not aware of the existence of such a letter which was sent to the judge,” said UN spokeswoman Sylvie van de Wildenberg to this journalist last fall when pressed for information about the case. “You know this is crazy, I don’t know why you are digging into it. Why are you in Haiti – are you here to help?”

Incensed by the news from Port Salut, demonstrators again descended on the area around the capital’s National Palace this week to call for MINUSTAH’s departure. Some held signs saying, “Justice for Gerard Jean-Gilles.” Police responded with tear gas which sent demonstrators and quake survivors running for cover around the makeshift tent camps that crowd the plaza.

The UN Security Council looks set to renew MINUSTAH’s mandate for at least another year before it expires on Oct. 15. While talk of a drawdown in troops is growing, UN officials say the force is likely to stay in Haiti until 2015.

“Let’s be serious,” James said. “The UN says that the judges are not efficient and the justice system should be reformed, while they block us from doing our job! I hope MINUSTAH doesn’t consider all Haitian to be idiots. To keep their positions, some Haitians are selling out the country and signing treaties in the name of Haitian people, but not all the Haitians are the same.”

Link:

The Death of Gérard Jean-Gilles: How the UN Stonewalled Haitian Justice | Haiti Liberte

SPACE IS FAKE

Say No To NASA!

Why is Haiti so important to the west

Secure Da Bag

Veteran

@loyola llothta why not merge this thread and your other thread. It's basically the same thing.

loyola llothta

☭☭☭

This thread is more on the 2004 UN occupation . the other thread is Haiti current situation to finally overthrow the US and the Core Group@loyola llothta why not merge this thread and your other thread. It's basically the same thing.

The UN left afew days ago. This thread is only for the past

loyola llothta

☭☭☭

loyola llothta

☭☭☭

U.S. Gvt. Channels Millions Through National Endowment for Democracy to Fund Anti-Lavalas Groups in Haiti

STORYJANUARY 23, 2006

STORYJANUARY 23, 2006

Link:We take a look at Haiti, which is preparing for upcoming national elections. Independent Canadian journalist, Anthony Fenton, joins us to discuss the National Endowment for Democracy–the US government-funded group–that is pouring millions of dollars into trying to influence Haiti’s political future. [includes rush transcript]

Nearly two years after the overthrow of President Jean Bertrand Aristide, Haiti will be holding national elections next month. Former President Rene Preval, a Aristide ally, is leading in the polls. Meanwhile, a judge has dropped the most serious charges against jailed priest Gerard Jean Juste. Jean Juste was imprisoned in July over the murder of journalist Jacques Roche–killed while Jean Juste was in Miami. After Jean Juste’s arrest, Haitian officials prevented Lavalas–the political movement aligned with Aristide–from registering him as their presidential candidate, on the grounds he was imprisoned. Although he has been cleared in Roche’s murder, authorities say Jean Juste will remain in prison over weapons charges. Amnesty International calls him a prisoner of conscience. Calls for his release have intensified with the recent announcement he’s been diagnosed with leukemia.

Meanwhile, violence continues to affect Haiti’s poorest areas. Last week, two Jordanian troops with the UN mission were killed in a gun-battle in the poor neighborhood of Cite Soleil. Local residents later reported UN troops had shot at a hospital in the area. UN troops have stepped up armed raids on Cite Soleil amid pressure from business leaders and foreign officials.

We want to continue our Haiti coverage leading up to the election by looking at the activities of a government-funded organization that is pouring millions of dollars into trying to influence the country’s political future. The National Endowment for Democracy is one of a handful of state-funded groups that have played a pivotal role in the internal politics of several Latin American and Caribbean countries in the service of the US government.

The NED operates with an annual budget of $80 million dollars from U.S. Congress and the State Department. In Venezuela, it’s given money to several political opponents of President Hugo Chavez. With elections underway in Haiti, it’s reportedly doing the same to groups linked to the country’s tiny elite and former military.

Last week Democracy Now! interviewed Anthony Fenton about NED’s activities in Haiti and across the Caribbean and Latin America. Fenton is an independent journalist and co-author of the book “Canada in Haiti: Waging War On The Poor Majority.” He has interviewed several top governmental and non-governmental officials dealing with Haiti as well as leading members of Haiti’s business community. Last month, he helped expose an NED-funded journalist who was filing stories for the Associated Press from Haiti. The Associated Press subsequently terminated its relationship with the journalist.

Last edited:

loyola llothta

☭☭☭

Transcript

This is a rush transcript. Copy may not be in its final form.

Link:

This is a rush transcript. Copy may not be in its final form.

AMY GOODMAN: Last week, I interviewed Anthony Fenton, about N.E.D.'s activities in Haiti and across the Caribbean and Latin America. Fenton is an independent Canadian journalist and co-author of the book, Canada in Haiti: Waging War on the Poor Majority. He has interviewed several top governmental and non-governmental officials dealing with Haiti, as well as leading members of Haiti's business community. Last month, he helped expose an N.E.D.-funded journalist who was filing stories for the Associated Press from Haiti. The Associated Press subsequently terminated its relationship with her. We go now to an excerpt from that interview. Anthony Fenton was in a studio in Vancouver. I began by asking him to talk about the current situation in Haiti.

ANTHONY FENTON: Well, indeed, obviously, there is an ongoing military occupation there ever since the forced ouster of President Jean-Bertrand Aristide in February of 2004 in a coup d’etat that was assisted and planned by the Canadian government, along with the U.S. government and the French government. Of course, speaking from Canada, Canada played an integral role in the overthrow of Aristide and continues to play an integral role in the post-invasion occupation of Haiti.

They’re leading up to what are now the fourth scheduled period of elections. There have been several postponements. This is due in part — the original intention of the invasion, of course, was to subvert the young process of popular democracy that existed in Haiti prior to the coup, and of course, if Aristide hadn’t been overthrown, Haiti would have already carried out their democratic election, their presidential elections.

And, of course, the fear of the United States and of organizations like the National Endowment for Democracy and the State Department, of course, was that popular democracy would take root in Haiti under another Lavalas government, and they have set about to undermine the popular movement that existed in support of Jean-Bertrand Aristide and the Lavalas Party. And we’re seeing today the consolidation of the elite rule that they have long envisioned for Haiti ever since the fall of “Baby Doc” Duvalier in the mid-80s.

AMY GOODMAN: Anthony, can you just lay out what the National Endowment for Democracy is?

ANTHONY FENTON: Well, yeah, they were formed in the early 1980s under the Reagan administration. Ostensibly, they purport to promote pro-democracy organizations and democratic values across the world. Just last October, President Bush spoke at a National Endowment for Democracy gathering, reiterating the vision of Reagan as he set about to, as they say, “promote democracy throughout the world,” and they were given — they’ve been given various budgets allocated by Congress every year, as you said at the onset. Now their budget stands at $80 million a year. But they are, of course, just one organization among many that are linked to the U.S. Agency for International Development, as I said, the State Department. Hundreds of millions of dollars now, in fact, more money is now being spent than ever before on what they call democracy promotion.

Now, the historical record on the National Endowment for Democracy is very clear, when we look at the work of people like Philip Agee and William Robinson and William Blum, Noam Chomsky and others, and most recently, if we look at the work of attorney and independent journalist, Eva Golinger, who exposed, through Freedom of Information Act requests, the role that the N.E.D. played in attempting to subvert democracy and the revolutionary process that’s unfolding in Venezuela in 2002. The N.E.D. played a crucial role in fomenting the opposition to Hugo Chavez, and they did play a role in the attempted coup against him in April of 2002, and very much the same patterns we have seen develop in Haiti.

On your show, in 2004, you interviewed Max Blumenthal, who wrote an article, an important article for Salon that outlined the role of the International Republican Institute, and when we talk about the N.E.D., we can’t talk about them without also talking about the International Republican Institute and the other affiliated organizations. There’s a virtual labyrinth of these organizations that receive funding that’s specifically earmarked for the undermining of any widespread social movements, any rudiments of popular democracy that should manifest, either in Latin America or anywhere in the world.

So, again, this is sort of the premise of what the National Endowment for Democracy really does, and as we look at what they’re doing in Haiti — and how I was able to learn about what they’re currently doing in Haiti came about through the process of a first documentary reporting trip to Haiti in September and October of 2005, where we spoke to a number of N.E.D. grantees, Haitian organizations that received funding from the National Endowment for Democracy. I returned to Canada and set about to conduct a series of interviews with N.E.D. and any program officer, in particular, with I.R.I. officials, with in-country officials who are managing several million dollars in U.S.-funded democracy promotion activities, as you said also, that are linked closely to the Haitian elite, to the opposition organizations, such as the Group of 184, the Democratic Convergence. These are the organizations that agitated most strongly for the overthrow of Aristide and that were working with the N.E.D. and the I.R.I. in the years preceding the 2004 coup.

AMY GOODMAN: The I.R.I. being the International Republican Institute.

ANTHONY FENTON: Yes. We know that — for example, just the other day, I spoke to a woman who is the leader of an organization called COFEL. It’s an umbrella organization of women political leaders. In the years before the coup against Aristide in 2004, the I.R.I. would bring in, they would bus in or fly in groups of anywhere between 60 and 80 of these women. And, of course, they’re busing in other men and other political figures in Haiti. But they would bus them into the Dominican Republic, because in 1999, at the time, Ambassador Timothy Carney — he was the U.S. ambassador at the time. That’s very important, because Ambassador Carney is the current interim ambassador to Haiti, and he was also a member of the lobby — the think tank in Washington called the Haiti Democracy Project that played an integral role in fomenting this demonization campaign against Aristide.

In any case, in 1999, the I.R.I. was closed down. Their operations were shut down. They were forced to leave Haiti, and until the coup in 2004, the I.R.I. did not have an in-country presence, so they were doing most of their work in the Dominican Republic with people like Stanley Lucas, who is well known as a card-carrying Republican Haitian American who was hired by the International Republican Institute during the first coup period against Aristide in the early 1990s, and he’s the one who sort of helped to build the political opposition from the Dominican Republic and enable the coup to take place. But that process has just followed through since the coup. Well, of course, the International Republican Institute now has an in-country office in Haiti, and through that office they’re able to penetrate all sectors of Haitian civil society in their attempt to undermine the popular movement.

Now, I would like to mention that in my interview, and this is a rare interview with an N.E.D. program officer, and this is the program officer in Washington who is responsible for Haiti currently, a woman named Fabiola Cordoba. She took over in, I believe in, November, as the program officer, and she revealed to me, not only an extensive list of documents that show the N.E.D.'s approved grants for 2005. These are, in a sense, declassified, because these are documents that are not supposed to be published until May of 2006, at least according to another N.E.D. spokesperson. But what's clear in these documents is that the N.E.D. went from, for example, a zero dollar budget in Haiti in 2003 to a $540,000 budget in Haiti in 2005.

What they’ve also done — and many Haitian people that I speak to have told me that Haiti is considered the laboratory for these sort of subversive activities on the part of the United States government. And in the context of this experimental process, they’ve hired, for the first time, an in-country program officer, as you mentioned, Régine Alexandre, who was a stringer for the Associated Press and the New York Times, was doubling, moonlighting as an N.E.D. program officer, and the Associated Press severed ties with her as a result.

Now, Fabiola Cordoba also told me that when she was in Haiti in 2002, working for one of the N.E.D.'s affiliated organizations, the National Democratic Institute, she said a lot of lines were being drawn between Haiti and Venezuela, where although 70% of the population supported Aristide, there was a very fragmented opposition. The rest of the 30% was divided between 120 different opposition groups, so the objective of the I.R.I. and the N.E.D. was to consolidate this opposition to build a viable opposition to somehow break the grip that the popular movement in Haiti had on the political environment there. And she said that Chavez — something very similar was happening in Venezuela, and of course, in 2002, the coup d'état happened there on the basis of this sort of analysis, the basis, this fear that the United States has of popular democracy and the need to subvert any attempts at consolidating popular rule and implementing policies that are in the interests of the majority poor in places like Venezuela and Haiti.

Link:

Last edited:

loyola llothta

☭☭☭

AMY GOODMAN: We’re talking to Anthony Fenton, independent author and journalist who has exposed a A.P. stringer in Haiti, Régine Alexandre, as also being on the payroll of the National Endowment for Democracy. And now talking about those parallels between Haiti and Venezuela, of course, 2002, the attempted coup against Hugo Chavez, what is your understanding of the U.S. involvement in terms of the, you know, dollar amount in Venezuela, putting money into the opposition?

ANTHONY FENTON: Well, it is very interesting, because since the activities of the N.E.D. have been so thoroughly exposed by the likes of Eva Golinger and Jeremy Bigwood through The Chavez Code, they’re very concerned with their perception in the area. So what they’re doing, in a way, they’ve continued to funnel large amounts of money into Venezuela, but they’re doing it also by outsourcing, if you will. For example, they have given a grant to a Canadian think tank called the Canadian Foundation of the Americas, and through that, they’re attempting to go through the back door, if you will, riding the perception of Canada as being a benign counterweight to the U.S. in the hemisphere, in order to penetrate Venezuelan civil society.

This is an important year, of course, not only in Venezuela, but throughout the hemisphere, in the sense that there are many presidential elections taking place. Now the N.E.D. program officer told me that Venezuela, Haiti, Ecuador, and Bolivia are the four top priority countries for the N.E.D. in 2006, looking ahead to 2006 and, of course, Cuba is the perennial top of that list. They’re a special exception, because the Department of State earmarks a certain amount of funds for the N.E.D.’s work in Cuba. In fact, they doubled the amount of money being used to subvert revolutionary Cuba in 2005.

Now, what they’re doing with the Foundation of the Americas is, in fact, on the board of directors there you have a former coup plotter in the form of Beatrice Rangel, who not only played an active role, when she was an advisor to former Venezuelan president Perez in the late 1980s, literally carrying bags of money, according to William Robinson, to Nicaraguan Contras operating out of Venezuela, but she is the person, Rangel, who facilitated this N.E.D. program with this Canadian think tank, and she herself said that, you know, Canada enjoys this perception, and N.E.D.’s outsourcing to Canada is just another way for the N.E.D. to penetrate Venezuelan civil society.

But in the case of Haiti, getting back to that point, what we’re seeing is the N.E.D. works very closely with the International Republican Institute. One of the N.E.D.'s primary grantees in Haiti is a key member of the Group of 184 political opposition to Aristide, named Hans Tippenhauer. He heads up an organization that works with Haitian youth. Typically we see the N.E.D. working with Haitian youth, with Haitian women, but what they're doing — Mr. Tippenhauer, he was one of the first people to call the rebels, the paramilitaries that entered from the Dominican Republic in 2004, he referred to them as “freedom fighters,” and he get grants from, not only the N.E.D., but also the I.R.I., and he also happens to be on the campaign of an independent presidential candidate named Charles Henri Baker, who was also one of the leaders of the Group of 184. He’s a sweatshop owner there and a brother-in-law of Andy Apaid, another leader of the Group of 184, who recently has been pressuring, with other members of the elite, such as Reginald Boulos, for the United Nations [inaudible] to force to enter the poor neighborhoods and commit more atrocities, so as to enable this process of consolidating elite rule in Haiti to take root.

And so, Hans Tippenhauer, as he doubles as a campaign manager for the Group 184 political candidate, the business candidate, basically a candidate that the U.S. is supporting, he is also working to penetrate Haitian civil society on a level that will allow, in the long term, this neo-liberal vision, this corporate vision of Haiti to take root, the so-called democracy, because the National Endowment for Democracy does promote some form of democracy. It’s a very narrow institutional form, kind of like we see in Canada.

It is ironic that we have elections going on here in Canada right now, but we don’t see the National Endowment for Democracy or the International Republican Institute here trying to manipulate the political environment, because we’re already on page with the State Department. We’re already on page with the N.E.D., so we don’t need their guidance, but a place like Haiti, where there were — where popular democracy was beginning to take root, even though in the face of a massive economic embargo and in the face of destabilization by these very organizations, it is very necessary that these organizations are in Haiti right now playing this fundamental role, behind the scenes, I should say, because the mainstream media has not written a single story about what these organizations are doing behind the scenes to effect political change in Haiti today.

AMY GOODMAN: Independent journalist, Anthony Fenton. We will return with him in a minute.

Link:

Last edited: