Good article. No spin. No bias. Just facts.  @FAH1223 @Gil Scott-Heroin

@FAH1223 @Gil Scott-Heroin

When it comes to scrutiny over television ratings, every league has its turn in the barrel — MLB every October that does not include New York or Los Angeles; the NHL in most years; even the NFL a few years ago. Yet there may be no greater spotlight than on NBA ratings, a recurring opportunity to air grievances about the game, its players, and topics far beyond the world of sports.

NBA ratings are once again the center of sports media discussion, making it a good time to once again examine the numbers and see exactly where the league currently stands — not just in relation to last year, or more than a decade ago, but to the rest of sports and television.

The NBA’s declines are discussed largely in isolation, creating the popular perception that it is the only league whose viewership is down, the only league whose viewership is down considerably from a decade-plus ago, and that the decline is disastrous. The first two of those claims are demonstrably untrue, and the other unconvincing.

To begin with, it is worth addressing the suggestion that the NBA’s decline is happening in isolation at a time when other leagues are thriving. To be sure, the NFL is thriving. So too is SEC football and Caitlin Clark-fueled women’s basketball. (Major League Baseball had a good year, but that is more akin to the NBA’s strong 2023 postseason, the result of having the highest-profile teams make deep runs.) The broader landscape is closer to what the NBA is experiencing this season. Men’s college basketball is down 21 percent, women’s college games are down 38 percent (owing in part to last year’s Clark boost), and the NHL is down 28 percent.

Even college football is down across all networks (albeit by a modest single-digit percentage), a seemingly impossible statistic if one only pays attention to the success of the SEC on ABC. Yet the SEC on ABC is but one conference on one network, and if anything has siphoned away viewership from other conferences on other networks (just ask Fox executives about their shrinking “Big Noon” audience).

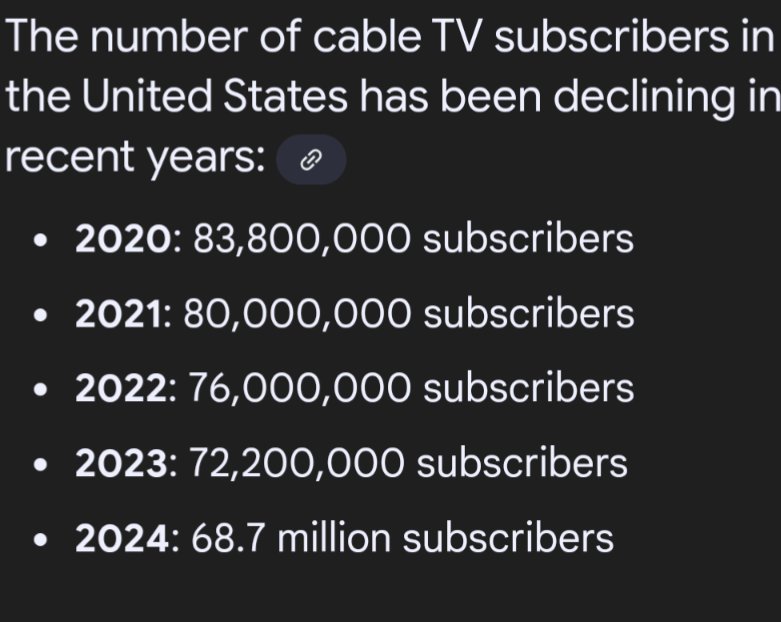

Even if one takes as fact the broadly-parroted 48 percent decline for NBA games from 2012 — a stat that, again, compares this year’s pre-Christmas average to a season that began on the holiday — it is not out of step with the broader trend. Versus the same 2011-12 benchmark, viewership for Major League Baseball, college football and men’s college basketball is down about 40 percent. Perhaps most importantly, people using television is down 52% to fewer than 50 million, and cable homes are down a third. (The NFL, it should be noted, is down just four percent over that period.)

None of the above is to suggest that the NBA is thriving as a television property, merely that the persistent claim that the league is tanking in some unique and unprecedented way remains as untrue now as it was in 2020.

No league makes — or loses — money solely based on the ratings, and for media companies, the ratings are increasingly beside the point compared to having a tonnage of content. The only data points with any tangible impact on the business of the NBA are generally positive, from the financial windfall and increased television coverage of the new media rights deal to the rising franchise values that are now the norm in all sports. (It also bears noting that even the diminished ratings remain a relative strength for the league, which even now is one of the only sports properties consistently generating seven-figure audiences.)

Even if this year’s ratings are part of a prolonged and worsening decline in popularity — and given the fickleness of television viewing, that is impossible to say with any confidence — by the time the NBA might face any financial consequences for the numbers, the entire makeup of the league (and media) will have changed. If leagues are not suffering consequences for low ratings now, it is hard to imagine that will have changed by 2036.

Yet if one is to move forward with that comparison, it is also worth noting a key difference between a political campaign and a sports league. A drop in popularity can be fatal for a campaign, no matter the money raised. For sports leagues, the money is the goal — and it has continued to grow, virtually across the board, regardless of declines in viewership (which are but one measure of popularity).

Much like the league as a whole, the Lakers have a lot of detractors heavily invested in their failure, and thus a subpar start for them is discussed much like a historically awful start might be for another team.

The NBA is undoubtedly off to a subpar start this season, but that is no surprise for a league whose best-known players are pushing 40, whose top teams are short on charisma, and whose games are still — for a few more months — primarily tethered to cable. One might even argue that the ratings indicate a dissatisfaction with the product indicative of real problems with the quality of the game, though to be frank that is an opinion in search of data to back it up. While the league has addressed one of these problems with the new media rights deal, which includes dramatically more games on broadcast television, the other issues will be a challenge to overcome.

Yet anyone who has observed sports media for any length of time knows that ratings ebb and flow with rarely any practical effect. Every single league has slumped for a few years and bounced back, then slumped again. The NBA in particular has surged and slumped every few years for the past four decades, and each trough has been accompanied by concerns about the future of the league — from the “Why the NHL is hot and the NBA is not” Sports Illustrated cover in 1994 to the “thugs and punks” gripes of 2004, to the present day. Paired with the new rights deal, prognostications of disaster over the current ebb seem premature at best and — especially coming from those who promised that the league would soon go ‘broke’ — hard to take seriously.

@FAH1223 @Gil Scott-Heroin

@FAH1223 @Gil Scott-HeroinWhen it comes to scrutiny over television ratings, every league has its turn in the barrel — MLB every October that does not include New York or Los Angeles; the NHL in most years; even the NFL a few years ago. Yet there may be no greater spotlight than on NBA ratings, a recurring opportunity to air grievances about the game, its players, and topics far beyond the world of sports.

NBA ratings are once again the center of sports media discussion, making it a good time to once again examine the numbers and see exactly where the league currently stands — not just in relation to last year, or more than a decade ago, but to the rest of sports and television.

Where NBA ratings currently stand

Through Saturday, NBA games were averaging 1.4 million viewers across ABC, ESPN and TNT — down 19 percent from last year (with NBA TV included, the decline swells to 25 percent).The NBA’s declines are discussed largely in isolation, creating the popular perception that it is the only league whose viewership is down, the only league whose viewership is down considerably from a decade-plus ago, and that the decline is disastrous. The first two of those claims are demonstrably untrue, and the other unconvincing.

To begin with, it is worth addressing the suggestion that the NBA’s decline is happening in isolation at a time when other leagues are thriving. To be sure, the NFL is thriving. So too is SEC football and Caitlin Clark-fueled women’s basketball. (Major League Baseball had a good year, but that is more akin to the NBA’s strong 2023 postseason, the result of having the highest-profile teams make deep runs.) The broader landscape is closer to what the NBA is experiencing this season. Men’s college basketball is down 21 percent, women’s college games are down 38 percent (owing in part to last year’s Clark boost), and the NHL is down 28 percent.

Even college football is down across all networks (albeit by a modest single-digit percentage), a seemingly impossible statistic if one only pays attention to the success of the SEC on ABC. Yet the SEC on ABC is but one conference on one network, and if anything has siphoned away viewership from other conferences on other networks (just ask Fox executives about their shrinking “Big Noon” audience).

The longer-term trend

One might wonder why so many viral NBA ratings posts compare today’s viewership to 2012. That was the lockout-shortened season which began on Christmas Day and generated the highest NBA viewership average of the post-Jordan era, part of a short-lived viewership boom occurring after LeBron James signed with Miami. It is not necessarily unfair to compare present-day viewership to a past peak, but it is certainly misleading to omit key context about that 2011-12 lockout season, in which there were no games in October, November or most of December — widely accepted as the weakest points of an NBA season. (It would be impossible to compare this year’s current viewership average to the same date in the 2011-12 campaign, as there had been literally no games played.)Even if one takes as fact the broadly-parroted 48 percent decline for NBA games from 2012 — a stat that, again, compares this year’s pre-Christmas average to a season that began on the holiday — it is not out of step with the broader trend. Versus the same 2011-12 benchmark, viewership for Major League Baseball, college football and men’s college basketball is down about 40 percent. Perhaps most importantly, people using television is down 52% to fewer than 50 million, and cable homes are down a third. (The NFL, it should be noted, is down just four percent over that period.)

None of the above is to suggest that the NBA is thriving as a television property, merely that the persistent claim that the league is tanking in some unique and unprecedented way remains as untrue now as it was in 2020.

What do the ratings mean?

For the NBA, which is in the final season before a new, 11-year media rights deal worth a total of $77 billion, ratings may matter less now than at any point in league history. Many of the same people trumpeting the NBA ratings decline this season were predicting that the league would take less money in its media rights negotiations, as opposed to the tripling of rights fees that actually occurred.No league makes — or loses — money solely based on the ratings, and for media companies, the ratings are increasingly beside the point compared to having a tonnage of content. The only data points with any tangible impact on the business of the NBA are generally positive, from the financial windfall and increased television coverage of the new media rights deal to the rising franchise values that are now the norm in all sports. (It also bears noting that even the diminished ratings remain a relative strength for the league, which even now is one of the only sports properties consistently generating seven-figure audiences.)

Even if this year’s ratings are part of a prolonged and worsening decline in popularity — and given the fickleness of television viewing, that is impossible to say with any confidence — by the time the NBA might face any financial consequences for the numbers, the entire makeup of the league (and media) will have changed. If leagues are not suffering consequences for low ratings now, it is hard to imagine that will have changed by 2036.

What do the ratings really mean?

Of course, it would not be entirely realistic to expect that discussion of NBA ratings is related to concerns about the league’s financial viability. The spotlight on NBA ratings has always been linked to broader societal issues. So it is that the NBA was recently compared on-air to the Democratic party, no real surprise considering that a lot of anti-NBA sentiment stems from the league’s unusually overt social stances in the progressive fervor of summer 2020. There may be something to the idea that the NBA, much like the Democrats, remains intrinsically linked with widely unpopular social stances, even as the league has largely dropped its 2020-era messaging.Yet if one is to move forward with that comparison, it is also worth noting a key difference between a political campaign and a sports league. A drop in popularity can be fatal for a campaign, no matter the money raised. For sports leagues, the money is the goal — and it has continued to grow, virtually across the board, regardless of declines in viewership (which are but one measure of popularity).

So what is the state of the NBA?

It may seem incongruous to suggest that there is ‘nothing to see here’ in an NBA season where viewership is down double-digits and there are widespread complaints about the quality of play. Perhaps it is worthwhile to look at the NBA a bit like the Lakers, not the most flattering comparison on its face. The discussion surrounding the Lakers is extremely negative at almost all times, and the team has played some true stinkers this season in which they have looked like the dregs of the league. Yet as of Tuesday, L.A. is 14-12. Not great, but still in contention for their traditional trip to the Play-in Tournament.Much like the league as a whole, the Lakers have a lot of detractors heavily invested in their failure, and thus a subpar start for them is discussed much like a historically awful start might be for another team.

The NBA is undoubtedly off to a subpar start this season, but that is no surprise for a league whose best-known players are pushing 40, whose top teams are short on charisma, and whose games are still — for a few more months — primarily tethered to cable. One might even argue that the ratings indicate a dissatisfaction with the product indicative of real problems with the quality of the game, though to be frank that is an opinion in search of data to back it up. While the league has addressed one of these problems with the new media rights deal, which includes dramatically more games on broadcast television, the other issues will be a challenge to overcome.

Yet anyone who has observed sports media for any length of time knows that ratings ebb and flow with rarely any practical effect. Every single league has slumped for a few years and bounced back, then slumped again. The NBA in particular has surged and slumped every few years for the past four decades, and each trough has been accompanied by concerns about the future of the league — from the “Why the NHL is hot and the NBA is not” Sports Illustrated cover in 1994 to the “thugs and punks” gripes of 2004, to the present day. Paired with the new rights deal, prognostications of disaster over the current ebb seem premature at best and — especially coming from those who promised that the league would soon go ‘broke’ — hard to take seriously.

It is what it is

It is what it is