Ol’Otis

The Picasso of the Ghetto

Delphine LaLaurie - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

laves between 1831 and 1834 are mixed. Harriet Martineau, writing in 1838 and recounting tales told to her by New Orleans residents during her 1836 visit, claimed Lalaurie's slaves were observed to be "singularly haggard and wretched;" however, in public appearances Lalaurie was seen to be generally polite to black people and solicitous of her slaves' health,[9] and court records of the time showed that Lalaurie manumitted two of her own slaves (Jean Louis in 1819 and Devince in 1832).[11] Nevertheless, Martineau reported that public rumors about Lalaurie's mistreatment of her slaves were sufficiently widespread that a local lawyer was dispatched to Royal Street to remind LaLaurie of the laws relevant to the upkeep of slaves. During this visit, the lawyer found no evidence of wrongdoing or mistreatment of slaves by Lalaurie.[12]

Martineau also recounted other tales of Lalaurie's cruelty that were current among New Orleans residents in about 1836. She claimed that, subsequent to the visit of the local lawyer, one of Lalaurie's neighbors saw one of the LaLaurie's slaves, a twelve-year-old girl named Lia (or Leah), fall to her death from the roof of the Royal Street mansion while trying to avoid punishment from a whip-wielding Delphine LaLaurie. Lia had been brushing Delphine's hair when she hit a snag, causing Delphine to grab a whip and chase her. The body was subsequently buried on the mansion grounds. According to Martineau, this incident led to an investigation of the Lalauries, in which they were found guilty of illegal cruelty and forced to forfeit nine slaves. These nine slaves were then bought back by the Lalauries through the intermediary of one of their relatives, and returned to the Royal Street residences.[13] Similarly, Martineau reported stories that LaLaurie kept her cook chained to the kitchen stove, and beat her daughters when they attempted to feed the slaves.[14]

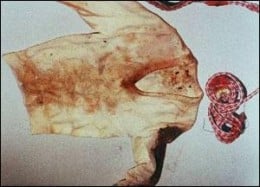

On April 10, 1834, a fire broke out in the LaLaurie residence on Royal Street, starting in the kitchen. When the police and fire marshals got there, they found a seventy-year-old woman, the cook, chained to the stove by her ankle. She later confessed to them that she had set the fire as a suicide attempt for fear of her punishment, being taken to the uppermost room, because she said that anyone who was taken there never came back. As reported in the New Orleans Bee of April 11, 1834, bystanders responding to the fire attempted to enter the slave quarters to ensure that everyone had been evacuated. Upon being refused the keys by the Lalauries, the bystanders broke down the doors to the slave quarters and found "seven slaves, more or less horribly mutilated ... suspended by the neck, with their limbs apparently stretched and torn from one extremity to the other", who claimed to have been imprisoned there for some months.[15]

One of those who entered the premises was Judge Jean-Francois Canonge, who subsequently deposed to having found in the LaLaurie mansion, among others, a "negress ... wearing an iron collar" and "an old negro woman who had received a very deep wound on her head [who was] too weak to be able to walk." Canonge claimed that when he questioned Madame Lalaurie's husband about the slaves, he was told in an insolent manner that "some people had better stay at home rather than come to others' houses to dictate laws and meddle with other people's business."[16]

A version of this story circulating in 1836, recounted by Martineau, added that the slaves were emaciated, showed signs of being flayed with a whip, were bound in restrictive postures, and wore spiked iron collars which kept their heads in static positions.[14]

When the discovery of the tortured slaves became widely known, a mob of local citizens attacked the Lalaurie residence and "demolished and destroyed everything upon which they could lay their hands".[15] A sheriff and his officers were called upon to disperse the crowd, but by the time the mob left, the Royal Street property had sustained major damage, with "scarcely any thing [remaining] but the walls."[17] The tortured slaves were taken to a local jail, where they were available for public viewing. The New Orleans Bee reported that by April 12 up to 4,000 people had attended to view the tortured slaves "to convince themselves of their sufferings."[17]

The Pittsfield Sun, citing the New Orleans Advertiser and writing several weeks after the evacuation of Lalaurie's slave quarters, claimed that two of the slaves found in the Lalaurie mansion had died since their rescue, and added, "We understand ... that in digging the yard, bodies have been disinterred, and the condemned well [in the grounds of the mansion] having been uncovered, others, particularly that of a child, were found."[18] These claims were repeated by Martineau in her 1838 book Retrospect of Western Travel, where she placed the number of unearthed bodies at two, including the child.[14]

laves between 1831 and 1834 are mixed. Harriet Martineau, writing in 1838 and recounting tales told to her by New Orleans residents during her 1836 visit, claimed Lalaurie's slaves were observed to be "singularly haggard and wretched;" however, in public appearances Lalaurie was seen to be generally polite to black people and solicitous of her slaves' health,[9] and court records of the time showed that Lalaurie manumitted two of her own slaves (Jean Louis in 1819 and Devince in 1832).[11] Nevertheless, Martineau reported that public rumors about Lalaurie's mistreatment of her slaves were sufficiently widespread that a local lawyer was dispatched to Royal Street to remind LaLaurie of the laws relevant to the upkeep of slaves. During this visit, the lawyer found no evidence of wrongdoing or mistreatment of slaves by Lalaurie.[12]

Martineau also recounted other tales of Lalaurie's cruelty that were current among New Orleans residents in about 1836. She claimed that, subsequent to the visit of the local lawyer, one of Lalaurie's neighbors saw one of the LaLaurie's slaves, a twelve-year-old girl named Lia (or Leah), fall to her death from the roof of the Royal Street mansion while trying to avoid punishment from a whip-wielding Delphine LaLaurie. Lia had been brushing Delphine's hair when she hit a snag, causing Delphine to grab a whip and chase her. The body was subsequently buried on the mansion grounds. According to Martineau, this incident led to an investigation of the Lalauries, in which they were found guilty of illegal cruelty and forced to forfeit nine slaves. These nine slaves were then bought back by the Lalauries through the intermediary of one of their relatives, and returned to the Royal Street residences.[13] Similarly, Martineau reported stories that LaLaurie kept her cook chained to the kitchen stove, and beat her daughters when they attempted to feed the slaves.[14]

On April 10, 1834, a fire broke out in the LaLaurie residence on Royal Street, starting in the kitchen. When the police and fire marshals got there, they found a seventy-year-old woman, the cook, chained to the stove by her ankle. She later confessed to them that she had set the fire as a suicide attempt for fear of her punishment, being taken to the uppermost room, because she said that anyone who was taken there never came back. As reported in the New Orleans Bee of April 11, 1834, bystanders responding to the fire attempted to enter the slave quarters to ensure that everyone had been evacuated. Upon being refused the keys by the Lalauries, the bystanders broke down the doors to the slave quarters and found "seven slaves, more or less horribly mutilated ... suspended by the neck, with their limbs apparently stretched and torn from one extremity to the other", who claimed to have been imprisoned there for some months.[15]

One of those who entered the premises was Judge Jean-Francois Canonge, who subsequently deposed to having found in the LaLaurie mansion, among others, a "negress ... wearing an iron collar" and "an old negro woman who had received a very deep wound on her head [who was] too weak to be able to walk." Canonge claimed that when he questioned Madame Lalaurie's husband about the slaves, he was told in an insolent manner that "some people had better stay at home rather than come to others' houses to dictate laws and meddle with other people's business."[16]

A version of this story circulating in 1836, recounted by Martineau, added that the slaves were emaciated, showed signs of being flayed with a whip, were bound in restrictive postures, and wore spiked iron collars which kept their heads in static positions.[14]

When the discovery of the tortured slaves became widely known, a mob of local citizens attacked the Lalaurie residence and "demolished and destroyed everything upon which they could lay their hands".[15] A sheriff and his officers were called upon to disperse the crowd, but by the time the mob left, the Royal Street property had sustained major damage, with "scarcely any thing [remaining] but the walls."[17] The tortured slaves were taken to a local jail, where they were available for public viewing. The New Orleans Bee reported that by April 12 up to 4,000 people had attended to view the tortured slaves "to convince themselves of their sufferings."[17]

The Pittsfield Sun, citing the New Orleans Advertiser and writing several weeks after the evacuation of Lalaurie's slave quarters, claimed that two of the slaves found in the Lalaurie mansion had died since their rescue, and added, "We understand ... that in digging the yard, bodies have been disinterred, and the condemned well [in the grounds of the mansion] having been uncovered, others, particularly that of a child, were found."[18] These claims were repeated by Martineau in her 1838 book Retrospect of Western Travel, where she placed the number of unearthed bodies at two, including the child.[14]

i used to be addicted to that no sleep subreddit

i used to be addicted to that no sleep subreddit

i should of not read this

i should of not read this There are some fukked up people on this spinning rock brehs

There are some fukked up people on this spinning rock brehs