Yeah like planes hitting three buildingsJust fukking terrifying.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

U.S. Drone Strike Said to Have Killed Ayman al-Zawahri, Top Qaeda Leader

- Thread starter 88m3

- Start date

More options

Who Replied?mastermind

Rest In Power Kobe

My perspective is the article @Rhakim shared an excerpt about a guy who is running his business and then hears a bomb drop from the sky and has PTSD from past drone bombings.I'm trying to understand your perspective here, your issue is the use of war machines against enemy combatants or the use of war machines in proximity of civilians?

The fact that no one wants to address that and that man's story lets me know that my point about Americans not seeing these people as a human is on the money.

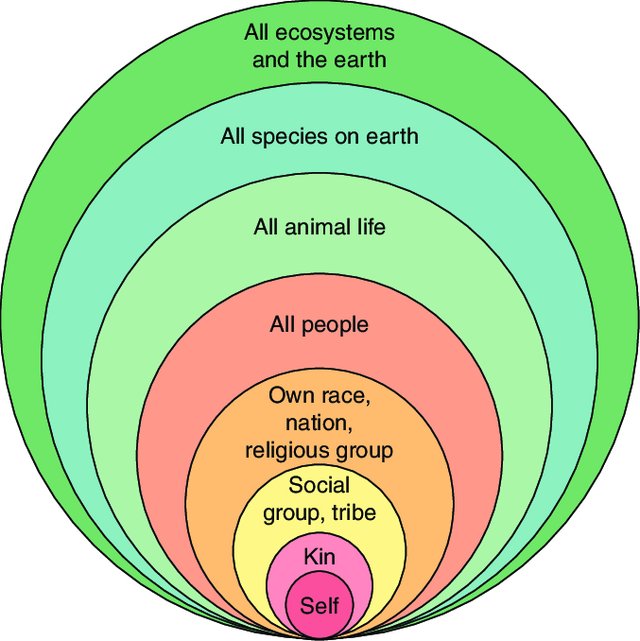

In reference to a rough illustration of Peter Singer's Expanding Circle:My perspective is the article @Rhakim shared an excerpt about a guy who is running his business and then hears a bomb drop from the sky and has PTSD from past drone bombings.

The fact that no one wants to address that and that man's story lets me know that my point about Americans not seeing these people as a human is on the money.

You are going to be very hard-pressed getting people to recognize the issue of collateral damage when people are overwhelming stuck at "Social group, tribe", at least in this country. I should note, I have no ( I have to think this out a bit more) problem with the use of drones when all casualties are legitimate combatants and it is taken into serious consideration before issuing the strike.

Now the lingering/indirect issues from the use of drones, I have to think more about that but it's likely going to be the case that they are justified when solely targeting combatants. I definitely see the argument you are getting, especially when considering what @Rhakim posted.

War is badMy perspective is the article @Rhakim shared an excerpt about a guy who is running his business and then hears a bomb drop from the sky and has PTSD from past drone bombings.

The fact that no one wants to address that and that man's story lets me know that my point about Americans not seeing these people as a human is on the money.

he's obviously talking about the everyday people who have to live in terror of a potential drone strike.Zawahiri?

they have a higher chance of being beheaded by the taliban than getting droned. especially if they aren't riding with terroristshe's obviously talking about the everyday people who have to live in terror of a potential drone strike.

ADevilYouKhow

Rhyme Reason

His arguments removed the Taliban of any necessity to not harbor war criminals.they have a higher chance of being beheaded by the taliban than getting droned. especially if they aren't riding with terrorists

But the bigger issue is simply asserting that the mere use of force doesn’t take into account the human element no matter what precautions are taken to limit or completely remove collateral damage.

The logic game he tried tor play about what would happen if this were in my community hinges heavily on the idea that I have no idea what’s going on it it and am therefore surprised when law enforcement conducts and armed raid or that I am aware of the criminal element and willingly turned a blind eye to it. Both are problematic in ways that undermine the entire premise so much that it not even worth going back and forth over.

That's pretty amateur - he's little just saying, "I'm right, I'm objectively right, and you're stupid if you don't believe me!" It's the position of someone who had spent much of his adult life to that point as a solider and a cop but not someone who had at all fully grappled intellectually with the positions of leaders like Gandhi who in his very age were fighting to free the very same brown people that Orwell was working as a cop to subdue.

The weakness of his intellectual argument is that it could be used to justify literally any atrocity, any war crime. "If you oppose anything we do in the war then you are hampering our war effort, and therefore you are pro-fascist!" By that sort of simplistic argument anyone who thinks our military actions should be bound by rules of engagement, who thinks we should avoid using biological or chemical weapons, who believes that targeting civilians is wrong, etc. - they can just as easily be accused of "hampering the war effort" and their objection tossed aside accordingly. And the opposing side can make the exact same intellectual argument for themselves and be equally valid.

Secure Da Bag

Veteran

So the care precision taken to limit the lack of civilian casualties doesn't prove that we don't view these people as humans?

Not necessarily. It could prove that we don't want to create more potential terrorists.

My perspective is the article @Rhakim shared an excerpt about a guy who is running his business and then hears a bomb drop from the sky and has PTSD from past drone bombings.

The fact that no one wants to address that and that man's story lets me know that my point about Americans not seeing these people as a human is on the money.

he's obviously talking about the everyday people who have to live in terror of a potential drone strike.

I should step in and clarify - the purpose of my initial post and the direction the conversation turned were actually different, though end up closely connected.

My reason for posting the initial article was because of the quotes suggesting that at least some residents of Kabul and wider Afghanistan, perhaps most, desperately don't want the USA to get involved in a shooting war again and are fearful even of the specter of a single drone strike. I hadn't heard that perspective in any recent Afghan reporting, though admittedly like most Americans I've been only paying minor attention to the going-ons there.

So my question in posting was - is this really the position of most everyday Afghans? And if so, what does that make us think about the intervention and the withdrawal?

Due to the direction of the conversation afterwards, the question became "How are regular citizens affected by the drone strikes?", which is a separate question from how they would feel about a returning American occupation. Though of course understanding one could do a lot to inform our understanding of the other.

This is fantasylandNot necessarily. It could prove that we don't want to create more potential terrorists.

they have a higher chance of being beheaded by the taliban than getting droned. especially if they aren't riding with terrorists

That clearly brings great comfort to them. You can see all the comfort when you read the articles about the day-to-day feelings of the actual people involved.

Drone strikes linked to "unprecedented" psychological trauma in Pakistan - Salon.com

"They are always apprehensive about the drones, about their lives," said Pehshawar psychiatrist

Living Under Drones | Stanford Law School

Living Under Drones: Death, Injury and Trauma to Civilians from US Drone Practices in Pakistan Related Organizations International Human Rights and Co

That full PDF report in the 3rd link in particular is very even-handed, academic, and extremely well-cited in an attempt to get at the various processes that led to the situation at the time of the report's writing, as opposed to posts here (including my own) which are largely partisan. Chapter 3 is the portion that looks at the actual impacts of the attacks on civilians.

Here is the verbatim quote from that report that Conor quoted pieces of in the earlier Atlantic piece:

MENTAL HEALTH IMPACTS OF DRONE STRIKES AND THE PRESENCE OF DRONES

One of the few accounts of living under drones ever published in the US came from a former New York Times journalist who was kidnapped by the Taliban for months in FATA. In his account, David Rohde described both the fear the drones inspired among his captors, as well as among ordinary civilians: “The drones were terrifying. From the ground, it is impossible to determine who or what they are tracking as they circle overhead. The buzz of a distant propeller is a constant reminder of imminent death.” Describing the experience of living under drones as ‘hell on earth’, Rohde explained that even in the areas where strikes were less frequent, the people living there still feared for their lives.

Community members, mental health professionals, and journalists interviewed for this report described how the constant presence of US drones overhead leads to substantial levels of fear and stress in the civilian communities below. One man described the reaction to the sound of the drones as “a wave of terror” coming over the community. “Children, grown-up people, women, they are terrified. . . . They scream in terror.” Interviewees described the experience of living under constant surveillance as harrowing. In the words of one interviewee: “God knows whether they’ll strike us again or not. But they’re always surveying us, they’re always over us, and you never know when they’re going to strike and attack.” Another interviewee who lost both his legs in a drone attack said that “[e]veryone is scared all the time. When we’re sitting together to have a meeting, we’re scared there might be a strike. When you can hear the drone circling in the sky, you think it might strike you. We’re always scared. We always have this fear in our head.”

A Pakistani psychiatrist, who has treated patients presenting symptoms he attributed to experience with or fear of drones, explained that pervasive worry about future trauma is emblematic of “anticipatory anxiety,” common in conflict zones. He explained that the Waziris he has treated who suffer from anticipatory anxiety are constantly worrying, “‘when is the next drone attack going to happen? When they hear drone sounds, they run around looking for shelter.” Another mental health professional who works with drone victims concluded that his patients’ stress symptoms are largely attributable to their belief that “[t]hey could be attacked at any time.”

Uncontrollability—a core element of anticipatory anxiety—emerged as one of the most common themes raised by interviewees. Haroon Quddoos, a taxi driver who survived a first strike on his car, only to be injured moments later by a second missile that hit him while he was running from the burning car, explained:

"We are always thinking that it is either going to attack our homes or whatever we do. It’s going to strike us; it’s going to attack us . . . . No matter what we are doing, that fear is always inculcated in us. Because whether we are driving a car, or we are working on a farm, or we are sitting home playing . . . cards–no matter what we are doing, we are always thinking the drone will strike us. So we are scared to do anything, no matter what."

Interviewees indicated that their own powerlessness to minimize their exposure to strikes compounded their emotional and psychological stress. “We are scared. We are worried. The worst thing is that we cannot find a way to do anything about it. We feel helpless.” Ahmed Jan summarized the impact: “Before the drone attacks, it was as if everyone was young. After the drone attacks, it is as if everyone is ill. Every person is afraid of the drones.” One mother who spoke with us stated that, although she had herself never seen a strike, when she heard a drone fly overhead, she became terrified. “Because of the terror, we shut our eyes, hide under our scarves, put our hands over our ears.”487 When asked why, she said, “Why would we not be scared?"

A humanitarian worker who had worked in areas affected by drones stated that although far safer than others in Waziristan, even he felt constant fear:

"Do you remember 9/11? Do you remember what it felt like right after? I was in New York on 9/11. I remember people crying in the streets. People were afraid about what might happen next. People didn’t know if there would be another attack. There was tension in the air. This is what it is like. It is a continuous tension, a feeling of continuous uneasiness. We are scared. You wake up with a start to every noise."

In addition to feeling fear, those who live under drones–and particularly interviewees who survived or witnessed strikes–described common symptoms of anticipatory anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder. Interviewees described emotional breakdowns, running indoors or hiding when drones appear above, fainting, nightmares and other intrusive thoughts, hyper startled reactions to loud noises, outbursts of anger or irritability, and loss of appetite and other physical symptoms. Interviewees also reported suffering from insomnia and other sleep disturbances, which medical health professionals in Pakistan stated were prevalent. A father of three said, “drones are always on my mind. It makes it difficult to sleep. They are like a mosquito. Even when you don’t see them, you can hear them, you know they are there.” According to a strike survivor, “When the drone is moving, people cannot sleep properly or can’t rest properly. They are always scared of the drones.” Saeed Yayha, a day laborer who was injured from flying shrapnel in the March 17, 2011 jirga attack and must now rely on charity to survive, said:

I can’t sleep at night because when the drones are there . . . I hear them making that sound, that noise. The drones are all over my brain, I can’t sleep. When I hear the drones making that drone sound, I just turn on the light and sit there looking at the light. Whenever the drones are hovering over us, it just makes me so scared.

Akhunzada Chitan, a parliamentarian who occasionally travels to his family home in Waziristan reported that people there “often complain that they wake up in the middle of the night screaming because they are hallucinating about drones.”

Interviewees also reported a loss of appetite as a result of the anxiety they feel when drones are overhead. Ajmal Bashir, an elderly man who has lost both relatives and friends to strikes, said that “every person—women, children, elders—they are all frightened and afraid of the drones . . . [W]hen [drones] are flying, they don’t like to eat anything . . . because they are too afraid of the drones.” Another man explained that “We don’t eat properly on those days [when strikes occur] because we know an innocent Muslim was killed. We are all unhappy and afraid.”

Several Pakistani medical and mental health professionals told us that they have seen a number of physical manifestations of stress in their Waziri patients. Ateeq Razzaq and Sulayman Afraz, both psychiatrists, attributed the phenomenon in part to Pashtun cultural norms that discourage the expression of emotional or psychological distress. “People are proud,” Razzaq explained to us, “and it is difficult for them to express their emotions. They have to show that they are strong people.” Reluctant to admit that they are mentally or emotionally distressed, the patients instead “express their emotional ill health through their body symptoms,” resulting in what Afraz called “hysterical reactions,” or “physical symptoms without a real [organic] basis, such as aches, and pains, vomiting, etcetera.” The mental health professionals with whom we spoke told us that when they treat a Waziri patient complaining of generic physical symptoms, such as body pain or “headaches, backaches, respiratory distress, and indigestion,” they attempt to determine whether the patient has been through a traumatic experience. It is through this questioning that they have uncovered that some of their patients had experienced drones, or lost a relative in a drone strike.

Mental health professionals we spoke with in Pakistan also said that they had seen numerous cases of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)510 among their patients from Waziristan related to exposure to drone strikes and the constant presence of drones. For example, one psychiatrist described a female patient of his who:

was having shaking fits, she was screaming and crying . . . . I was guessing there might be some stress . . . then I [discovered] there was a drone attack and she had observed it. It happened just near her home. She had witnessed a home being destroyed–it was just a nearby home, [her] neighbor’s.

Interviewees also described the impacts on children. One man said of his young niece and nephew that “[t]hey really hate the drones when they are flying. It makes the children very angry.” Aftab Gul Ali, who looks after his grandson and three granddaughters, stated that children, even when far away from strikes, are “badly affected.” Hisham Abrar, who had to collect his cousin’s body after he was killed in a drone strike, stated:

When [children] hear the drones, they get really scared, and they can hear them all the time so they’re always fearful that the drone is going to attack them. . . Because of the noise, we’re psychologically disturbed—women, men, and children. . . Twenty-four hours, [a] person is in stress and there is pain in his head.

Noor Behram, a Waziri journalist who investigates and photographs drone strike sites, noted the fear in children: “if you bang a door, they’ll scream and drop like something bad is going to happen.” A Pakistani mental health professional shared his worries about the long-term ramifications of such psychological trauma on children:

The biggest concern I have as a [mental health professional] is that when the children grow up, the kinds of images they will have with them, it is going to have a lot of consequences. You can imagine the impact it has on personality development. People who have experienced such things, they don’t trust people; they have anger, desire for revenge . . . So when you have these young boys and girls growing up with these impressions, it causes permanent scarring and damage.

The small number of trained mental health professionals and lack of health infrastructure in North Waziristan exacerbates the symptoms and illnesses described here. Several interviewees provided a troubling glimpse of the methods some communities turn to in order to deal with mental illness in the absence of adequate alternatives. One man said that “some people have been tied in their houses because of their mental state.” A Waziri from Datta Khel—which has been hit by drone strikes over three dozen times in the last three years alone—said that a number of individuals “have lost their mental balance . . . are just locked in a room. Just like you lock people in prison, they are locked in a room.” Some of those interviewed reported that, to deal with their symptoms, they were able to obtain anti-anxiety medications and antidepressants. One Waziri man who lost his son in a drone strike explained that people take tranquilizers to “save them from the terror of the drones.” Umar Ashraf obtained a prescription for Lexotanil to treat “the mental issues I was facing,” and said that taking the medicine makes him feel better. Saeed Yayha, however, said that the prescription the doctors gave him to deal with “the pressure in his head” does not work for him; “t just soothes me for half an hour but it does not last very long.”

I don’t think anyone had any issues with the withdrawal. It was supported by Americans across the spectrum.So my question in posting was - is this really the position of most everyday Afghans? And if so, what does that make us think about the intervention and the withdrawal?

I don’t think there’s any appetite to return and the lingering question of whether the US could carry out its clandestine and anti-terror activities at a high level without a base seems to have been answered and further quelled the idea that we need a massive military footprint there.

I don’t think anyone had any issues with the withdrawal. It was supported by Americans across the spectrum.

I don’t think there’s any appetite to return and the lingering question of whether the US could carry out its clandestine and anti-terror activities at a high level without a base seems to have been answered and further quelled the idea that we need a massive military footprint there.

But the reasons for supporting withdrawal were almost entirely self-centered for most. We left because Americans were tired of being there, not because we cared what Afghans thought. Very much in line with what @mastermind was talking about. It's not just whether we should have pulled out in 2022, but why not 2012? Or perhaps we never should have been there at all? At least, if we consider Afghans just as human as ourselves, it's a position worth considering seriously and not dismissing because "bin Laden bad and thus all is justified, Afghans be damned".

The report I quoted extensively from was from Pakistan, where we never had a massive military footprint. Thus the conditions we created in Pakistan (and to a meaningful degree in many other countries, if you read other reports of the impacts of our drones in the Middle East and Africa) could be replicated in Afghanistan even without resuming occupation.