You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Thousands of dads left in shock as DIY paternity test usage soars

- Thread starter Rell Lauren

- Start date

More options

Who Replied?LeVraiPapi

Redemption is Coming

Wait, this thread isn't official until @LeVraiPapi aka "the real daddy" posts in it.

Breh, this might be over for them thots. No more free child support . As a Zoe, it's more likely we know . They will definitely look like us

Then why do so many countries ban DNA testing breh10% is high.

Just think of like this.

10% of the US population is 33 million people.

DNA paternity testing - Wikipedia

Even here in America in order to get a DNA test the doctor has to give you permission AND the mother also has to give permission. If it's such a low number why are there so many laws to prevent it

. Keep being naive though

. Keep being naive though  .

.Off topicNo, that's for shows like Richard Bay, Jerry Springer and the rest. But for the DNA testing, that's real. But like i will say again, they way they write it for TV, they have to script it around a story in a way the people will believe. It's all about ratings.

But I've been trying to remember that niggsz name for 4ever.. Richard Bay...

I've been trying to tell ppl there was a dude b4 Maury. His show was wild as hell... way before it was ok to be wild as hell.

I thought it was only a tri-stste area thing

Again.... this is not trueThere's a reason.

Uncle Sam not trying to be a simp and take care of these kids either.

They rather pin it on a sucker

AND THEY GONNA TAX IT

Steaight pimping you suckuz

Federal Child Support Laws That Impact Today's CasesAgain.... this is not true

History of child support

Breh make a thread on that article. The fact that you got so many naive brehs on this site is disgustingsome sources say 10%

newworldafro

DeeperThanRapBiggerThanHH

Jesus help me :Stopitnow:

Some of the Dual Citizen posters on LSA, has this story hit those shores? Reaction?

Last edited:

These lying heffas

I was watching paternity court and all these sweet little grannies were bringing out 40 year old grown adult children

“You are the father Joe!”

“Mabel you know that’s not my child, I was stationed in ‘Nam and when I got back you had a whole baby”

* Joe is not the father...

*Mabel is shocked...

(Meanwhile Joes real children are probably half Vietnamese)

The most interesting thing is that in most of these cases they were married too, the War was some reckless times

I was watching paternity court and all these sweet little grannies were bringing out 40 year old grown adult children

“You are the father Joe!”

“Mabel you know that’s not my child, I was stationed in ‘Nam and when I got back you had a whole baby”

* Joe is not the father...

*Mabel is shocked...

(Meanwhile Joes real children are probably half Vietnamese)

The most interesting thing is that in most of these cases they were married too, the War was some reckless times

Also think about this breh. We have more female ancestors than male ancestors and our ancestry goes back to a smaller percentage of males. This means that women were having kids with a small percentage of men. It's just nature breh. Paternity fraud is bound to happenJesus H Christ 50%

. Society forced women to get with men they aren't attracted to (80 20 rule) so they go out and have kids with the men they like

. Society forced women to get with men they aren't attracted to (80 20 rule) so they go out and have kids with the men they like  . They need the simp to pay for the id though

. They need the simp to pay for the id though  .

.https://psmag.com/environment/17-to-1-reproductive-success

Once upon a time, 4,000 to 8,000 years after humanity invented agriculture, something very strange happened to human reproduction. Across the globe, for every 17 women who were reproducing, passing on genes that are still around today—only one man did the same.

"It wasn't like there was a mass death of males. They were there, so what were they doing?" asks Melissa Wilson Sayres, a computational biologist at Arizona State University, and a member of a group of scientists who uncovered this moment in prehistory by analyzing modern genes.

Another member of the research team, a biological anthropologist, hypothesizes that somehow, only a few men accumulated lots of wealth and power, leaving nothing for others. These men could then pass their wealth on to their sons, perpetuating this pattern of elitist reproductive success. Then, as more thousands of years passed, the numbers of men reproducing, compared to women, rose again. "Maybe more and more people started being successful," Wilson Sayres says. In more recent history, as a global average, about four or five women reproduced for every one man.

ADVERTISEMENT

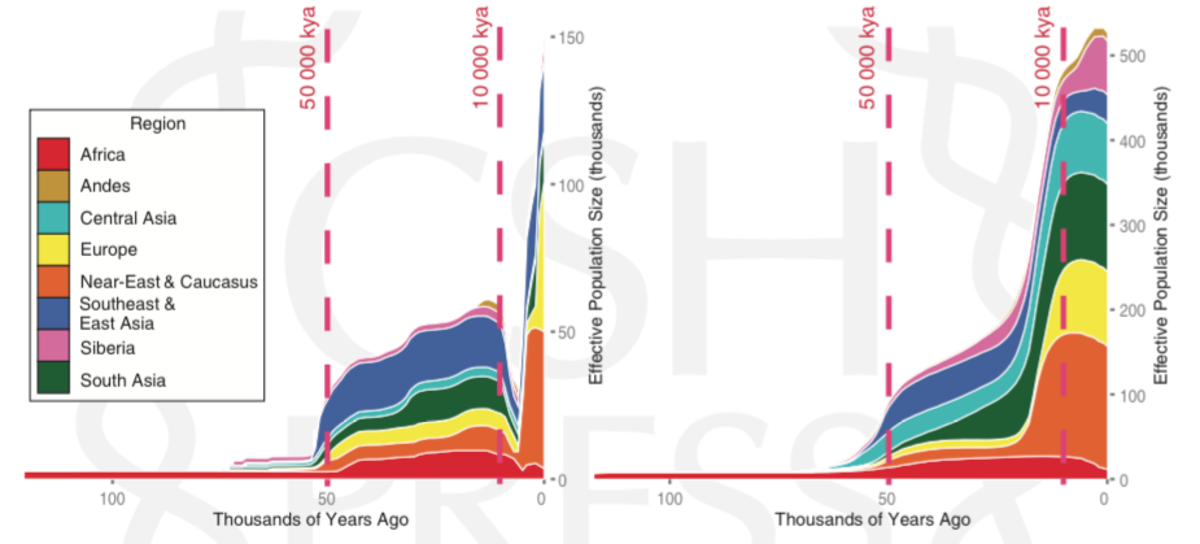

These two graphs show the number of men (left) and women (right) who reproduced throughout human history. (Chart: Monika Karmin et al./Genome Research)

Physically driven natural selection shaped many human traits. Ethnic Africans and Europeans had to evolve to digest milk, for example, while most ethnic Tibetans have adaptations to deal with the lower oxygen levels at high altitudes. But if Wilson Sayres' team's hypothesis is correct, it would be one of the first instances that scientists have found of culture affecting human evolution.

The team uncovered this dip-and-rise in the male-to-female reproductive ratio by looking at DNA from more than 450 volunteers from seven world regions. Geneticists analyzed two parts of the DNA, Y-chromosome DNA and mitochondrial DNA. These don't make up a large portion of a person's genetics, but they're special because people inherit Y-chromosome DNA exclusively from their male ancestors and mitochondrial DNA exclusively from their female ancestors. By analyzing diversity in these parts, scientists are able to deduce the numbers of female and male ancestors a population has. It's always more female.

"It wasn't like there was a mass death of males. They were there, so what were they doing?"

So much for what our DNA can tell us. This study, published last week in the journal Genome Research, can't directly account for why the dip occurred. Instead, the team members tried to think through other explanations. "Like was there some sort of weird virus that only affected males across the whole globe, 8,000 years ago?" Wilson Sayres asks—a hypothesis the team found unlikely.

To further test the wealth-and-power idea, the researchers plan to look for other genetic markers that would indicate that something cultural, not physical, kept those early male farmers from reproducing. Team members could also collaborate with anthropologists and archaeologists, to see if they have any clues.

Nature is a harsh taskmaster, but so, it seems, is human culture. Although the popular notion is that farming and settlement cushioned people against "survival of the fittest," this study shows that's not true. Something cultural happened 8,000 years ago that's marked us even today.

The part I was saying "no true" to... is the part about wanting to pin it on a sucka...

They just dont want to have to pay the bill for these kids..

If they make paternity test mandatory and the supposed father isn't the father... then the mother is gonna have to find the other joker... or get denied benefits...

The gov shouldnt care who pays for these kids.... the sucka, the real father or woman by themselves... as long as they're not paying for it...

But they arent making this mandatory for a reason...

To me, it's all apart of this whole agenda to keep painting women as innocent or always victims.

If we made this thing mandatory, all that crumbles...

Ppl always try to fall back on these really low percentages on false rapes and false paternity cases... but this would give us the real numbers on how often this type of fraud occurs.

And it won't be pretty

Last edited:

delete

The Fade

I don’t argue with niqqas on the Internet anymore

Females in here really acting oblivious and playing semantics

Yall gone learn

Most them in real life be on that “b-b-but technically” shyt. Always playing by technicalities and not the principle.

‘Technically’ deez nuts hoe :Ididit: