A Two-Pound Ukrainian Drone Just Shot Down A 12-Ton Russian Helicopter

It may be the first time a drone has destroyed a helicopter in mid-air.

www.forbes.com

www.forbes.com

A Two-Pound Ukrainian Drone Just Shot Down A 12-Ton Russian Helicopter

It may be the first time a drone has destroyed a helicopter in mid-air.

David Axe

Forbes Staff

David Axe writes about ships, planes, tanks, drones and missiles.

Jul 31, 2024,04:45pm EDT

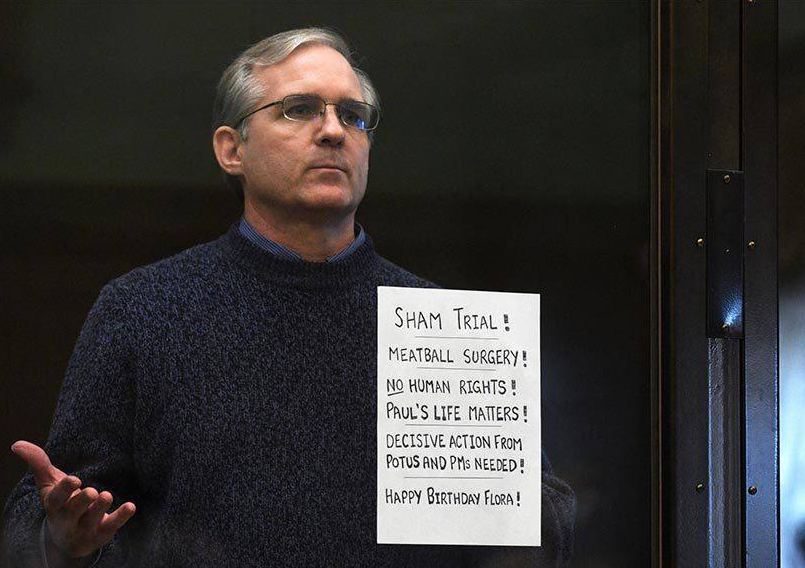

A Russian Mil Mi-8.

Vitaly V. Kuzmin photo

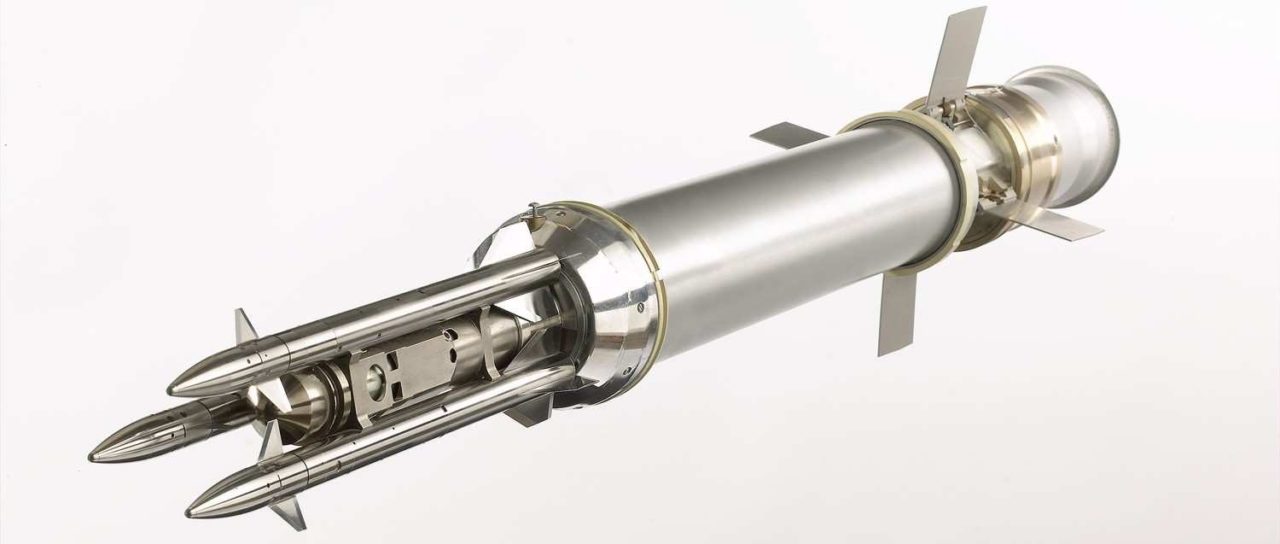

Ukrainian forces deploy more than 100,000 explosive first-person-view drones a month all along the 700-mile front line of Russia’s 28-month wider war on Ukraine. The drones smash into armored vehicles, chase down exposed infantry and follow artillery fire back to its origin in order to target Russian howitzers.

And today one of the small quadcopter drones—remotely steered by an operator wearing a virtual-reality headset—shot down a Russian helicopter, apparently for the first time.

Photos and videos that circulated on social media depict the Mil Mi-8 transport helicopter burning near Donetsk in Russian-occupied eastern Ukraine. “A speedy recovery to the survivors,” one Russian blogger wrote.

This new use of explosive drones has been a long time coming. As long ago as September, Ukrainian operators first tried ramming their flying robots into Russian helicopters mid-flight. The drone threat got so serious that the Russian air force began assigning some helicopters to escort other helicopters.

It apparently took at least 10 months of trying before a Ukrainian drone operator finally hit a Russian helicopter. The months of misses are understandable. A helicopter can fly faster than 150 miles per hour at altitudes exceeding thousands of feet—too fast and too high for a two-pound drone to get a clean shot without an enormous degree of skill or luck on the part of the operator.

The Ukrainian drone pilot in the Wednesday shoot-down was very skilled or lucky—or both. They spotted the 12-ton, three-crew Russian helicopter—which performs attack, transport and medical-evacuation missions—while it was still close to the ground. “Caught at the moment of takeoff,” a Russian blogger reported.

An FPV drone normally carries just a few pounds of explosives. But it doesn’t take much firepower to knock down a helicopter if it takes a hit it in the rotors.

After more than two years of war, Ukrainian drone operators have become extremely adept at targeting the most vulnerable parts of Russian targets: flying drones into the open hatches of armored personnel carriers, under the add-on armor on so-called “turtle tanks” and through the doors of reinforced infantry dugouts.

Compared to a 36-inch-wide hatch, an Mi-8’s 12-foot-diameter rotor disc is an easy target.

What might be most impressive is how far the Russian helicopter may have been from the front line. The western edge of Donetsk is just three miles from the front line—well within the range of an unaided FPV drone.

But the eastern edge of the city is closer to 10 miles from the front line. That’s apparently where the shoot-down took place. “The distance,” the second blogger explained, “is very significant.”

To travel 10 miles, an FPV might need help from a second drone, trailing a few miles behind, that captures and rebroadcasts its short-range command signal. It’s a complex operation requiring careful coordination.

The Russian military has hundreds of helicopters and, so far, has lost just a hundred or so to Ukrainian action. One more loss isn’t catastrophic for the Russians. But now that the Ukrainians have droned their first helicopter, they may redouble their efforts to take down Russian rotorcraft.

Considering how many FPV drones the Ukrainians deploy every month, the threat to Russian helicopters could intensify—a lot.

Follow me on Twitter. Check out my website or some of my other work here. Send me a secure tip.