https://nymag.com/intelligencer/art...ook-message-israel-palestine-complicated.html social studies

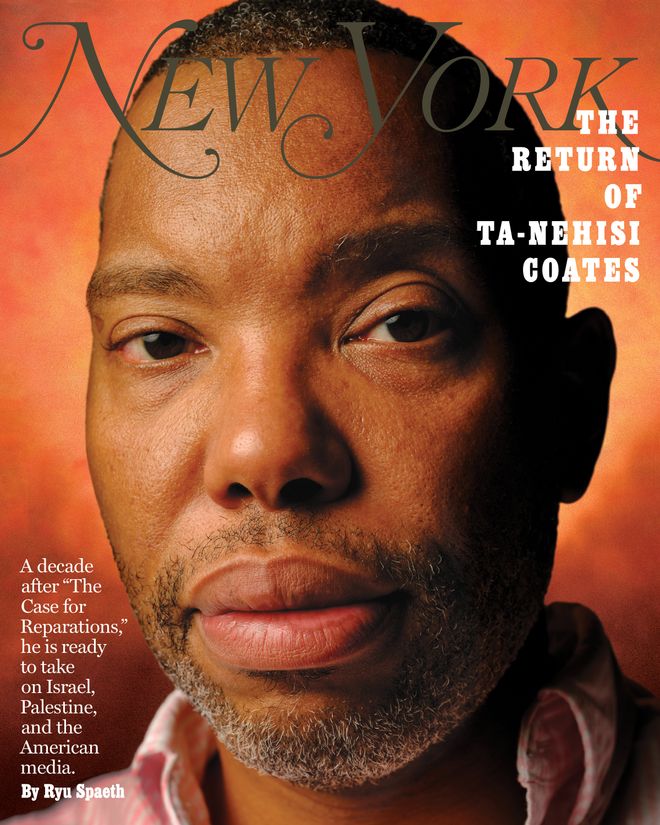

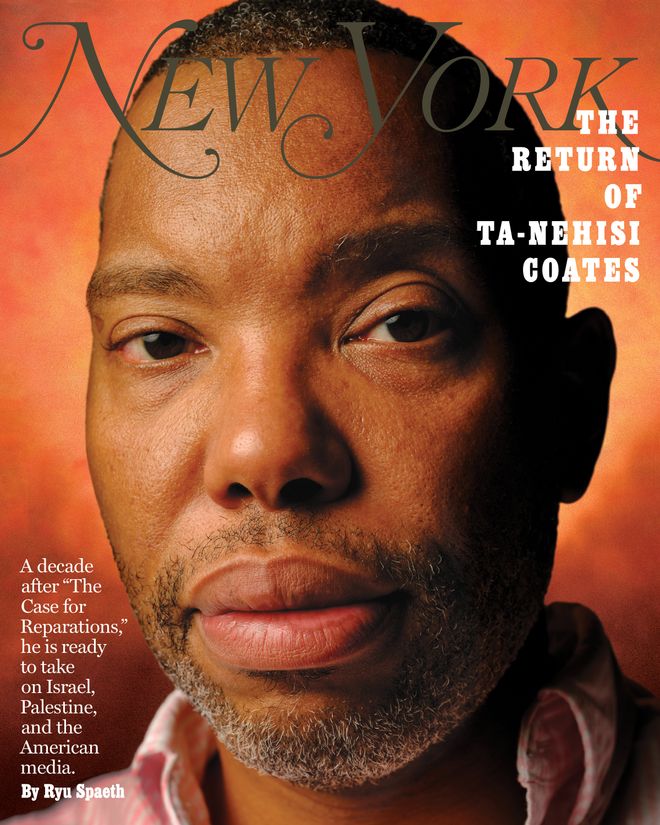

The Return of Ta-Nehisi Coates

443 Comments

social studies Sept. 23, 2024

By Ryu Spaeth, a features editor at New York

Ta-Nehisi Coates in the city of Lydd. “The site of a horrific massacre,” he said, “where, among other things, grenades were tossed into a mosque.” Photo: Rob Stothard

This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

It was mid-August, roughly a month and a half before his new book, The Message, was set to be published, and Ta-Nehisi Coates was in my face, on my level, his eyes wide and aflame and his hands swallowing his scalp as he clutched it in disbelief and wonder and rage. At the Gramercy Park restaurant where we’d met for breakfast, Coates, now 48, looked noticeably older than the fruit-cheeked polemicist whose visage had been everywhere nearly a decade before, when he released Between the World and Me, his era-defining book on race during the Obama presidency, and the stubble of his beard was now frosted with white. But he was possessed still with the conviction and anxiety of a young man: deeply certain that he is right and yet almost desperate to be confirmed. He spoke most of the Israeli occupation of the Palestinian territories, a central subject of his book. “I knew it was wrong from day one,” he said. “Day one — you know what I mean?”

The Message — a return to nonfiction after years of writing comics, screenplays, and a novel — begins with an epigraph from Orwell: “In a peaceful age I might have written ornate or merely descriptive books, and might have remained almost unaware of my political loyalties. As it is I have been forced into becoming a sort of pamphleteer.” Our own age of strife takes Coates to three places: Dakar, Senegal, where he makes a pilgrimage to Gorée Island and the Door of No Return; Chapin, South Carolina, where a teacher has been pressured to stop teaching Between the World and Me because it made some students feel “ashamed to be Caucasian”; and the West Bank and East Jerusalem. It is in the last of these long, interconnected essays that Coates aims for the sort of paradigm shift that first earned him renown when he published “The Case for Reparations” in The Atlantic in 2014, in which he staked a claim for what is owed the American descendants of enslaved Africans. This time, he lays forth the case that the Israeli occupation is a moral crime, one that has been all but covered up by the West. He writes, “I don’t think I ever, in my life, felt the glare of racism burn stranger and more intense than in Israel.”

See All

Coates traveled to the region on a ten-day trip in the summer of 2023. “It was so emotional,” he told me. “I would dream about being back there for weeks.” He had known, of course, in an abstract sense, that Palestinians lived under occupation. But he had been told, by journalists he trusted and respected, that Israel was a democracy — “the only democracy in the Middle East.” He had also been told that the conflict was “complicated,” its history tortuous and contested, and, as he writes, “that a body of knowledge akin to computational mathematics was needed to comprehend it.” He was astonished by the plain truth of what he saw: the walls, checkpoints, and guns that everywhere hemmed in the lives of Palestinians; the clear tiers of citizenship between the first-class Jews and the second-class Palestinians; and the undisguised contempt with which the Israeli state treated the subjugated other. For Coates, the parallels with the Jim Crow South were obvious and immediate: Here, he writes, was a “world where separate and unequal was alive and well, where rule by the ballot for some and the bullet for others was policy.” And this world was made possible by his own country: “The pushing of Palestinians out of their homes had the specific imprimatur of the United States of America. Which means that it had my imprimatur.”

That it was complicated, he now understood, was “horseshyt.” “Complicated” was how people had described slavery and then segregation. “It’s complicated,” he said, “when you want to take something from somebody.”

How could he have been so wrong before? The fault lay partly with the profession he loved. In journalism, he had found his voice, his platform, his purpose in life. And yet, as he sees it, it was journalistic institutions that had not only failed to tell the truth about Israel and Palestine but had worked to conceal it. As a result, a fog had settled over the region, over its history and present, obscuring what anyone at closer range could apprehend easily with their own two eyes.

The Message is an attempt to use the journalist’s tools to dispel this veil. Coates was successful in such an effort before, when far fewer Americans understood the material grip that the legacy of slavery had on the descendants of the enslaved. In the years after “The Case for Reparations” was published, Coates was initiated into elite rooms in New York, Washington, and Hollywood. He testified before Congress, won a National Book Award, was interviewed by Oprah. This son of West Baltimore found himself, by his early 40s, an esteemed member of the powerful whose message was welcomed. And many are now eager for Coates to lend his considerable influence to the deadlocked public conversation on Israel and Palestine. But The Message also unquestionably breaks with the Establishment that championed Coates, risking his standing and possibly his career. Journalist Peter Beinart, a vocal critic of Israel, said, “Ta-Nehisi has a lot to lose.”

There are, of course, many who believe that the moral dimensions of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict are indeed complicated. The most famous of Israel’s foundational claims — that it was a necessary sanctuary for one of the world’s most oppressed peoples, who may not have survived without a state of their own — is at the root of this complication and undergirds the prevailing viewpoint of the political-media-entertainment nexus. It is Israel’s unique logic of existence that has provided a quantum of justice to the Israeli project in the eyes of Americans and others around the world, and it’s what separates Jewish Israelis from the white supremacists of the Jim Crow South, who had no justice on their side at all. But for Coates, one wrong cannot justify another. “All states at their core have a reason for existing — a moral story to tell,” he told me. “We certainly do. Does industrialized genocide entitle one to a state? No.” Especially, he said, at the expense of people who had no hand in the genocide.

What matters to Coates is not what will happen to his career now — to the script sales, invitations from the White House, his relationships with his former colleagues at The Atlantic and elsewhere. “I’m not worried,” he told me, shrugging his shoulders. “I have to do what I have to do. I’m sad, but I was so enraged. If I went over there and saw what I saw and didn’t write it, I am fukking worthless.”

At a checkpoint in the old city of Hebron. “I get sad every time I look at this photo,” Coates said. “This was the second day of the trip and the moment I realized how similar what I was seeing was to the world my parents and grandparents were born into.” Photo: Courtesy of Ta-Nehisi Coates

Coates is hardly the first person to attempt to elucidate the plight of the Palestinians. Then again, he was not the first person to tackle the subject of reparations, a staple of classroom discussions and political debate. “I remember when he told me he was writing ‘The Case for Reparations,’” said Chris Jackson, the editor of The Message and Coates’s other books. “I was like, ‘Ta-Nehisi, you can’t Columbus reparations.’” Even within The Atlantic, there was skepticism. “My first reaction was, This sounds nuts,” said Scott Stossel, Coates’s editor at the magazine. “This is a nonstarter.”

Coates, however, had the enthusiastic support of The Atlantic’s then–editor-in-chief, James Bennet. “He’s one of those writers you trust when he proposes an idea,” Bennet told me recently. “He’s really almost singular.” In one of several conversations we had after our breakfast in Gramercy, Coates recalled, “I couldn’t believe that I’m talking about this theoretical case for reparations and this white dude is like, ‘Okay, so how big can we do it?’” Coates had already won a National Magazine Award for his 2012 article “Fear of a Black President,” analyzing the racial paradoxes of Obama’s first term, which had earned him trust and leverage. And he had a blog where he was proving that there was an immense readership for topics that might seem off the news, the most prominent and surprising of which was the Civil War. “The groundwork was laid by building up the audience to field-test his ideas,” said Stossel. “And he had a lot of smart readers who would give him feedback. He starts out from a point of almost radical humility, where he is open to critiques from anyone.” Bennet told me, “He just constantly learned; he was a learning machine.”

Coates was obsessed with the historical narratives about the Civil War — how they’d been formed and how they overlaid the present. “It’s kind of hard to remember, but even as late as 2014, people were talking about the Civil War as this complicated subject,” Jackson said. “Ta-Nehisi was going to plantations and hanging out at Monticello and looking at all the primary documents and reading a thousand books, and it became clear that the idea of a ‘complicated’ narrative was ridiculous.” The Civil War was, Coates concluded, solely about the South’s desire to perpetuate slavery, and the subsequent attempts over the next century and a half to hide that simple fact betrayed, he believed, a bigger lie — the lie that America was a democracy, a mass delusion that he would later call “the Dream” in Between the World and Me.

The Return of Ta-Nehisi Coates

443 Comments

social studies Sept. 23, 2024

The Return of Ta-Nehisi Coates

A decade after “The Case for Reparations,” he is ready to take on Israel, Palestine, and the American media.

By Ryu Spaeth, a features editor at New York

Ta-Nehisi Coates in the city of Lydd. “The site of a horrific massacre,” he said, “where, among other things, grenades were tossed into a mosque.” Photo: Rob Stothard

This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

It was mid-August, roughly a month and a half before his new book, The Message, was set to be published, and Ta-Nehisi Coates was in my face, on my level, his eyes wide and aflame and his hands swallowing his scalp as he clutched it in disbelief and wonder and rage. At the Gramercy Park restaurant where we’d met for breakfast, Coates, now 48, looked noticeably older than the fruit-cheeked polemicist whose visage had been everywhere nearly a decade before, when he released Between the World and Me, his era-defining book on race during the Obama presidency, and the stubble of his beard was now frosted with white. But he was possessed still with the conviction and anxiety of a young man: deeply certain that he is right and yet almost desperate to be confirmed. He spoke most of the Israeli occupation of the Palestinian territories, a central subject of his book. “I knew it was wrong from day one,” he said. “Day one — you know what I mean?”

The Message — a return to nonfiction after years of writing comics, screenplays, and a novel — begins with an epigraph from Orwell: “In a peaceful age I might have written ornate or merely descriptive books, and might have remained almost unaware of my political loyalties. As it is I have been forced into becoming a sort of pamphleteer.” Our own age of strife takes Coates to three places: Dakar, Senegal, where he makes a pilgrimage to Gorée Island and the Door of No Return; Chapin, South Carolina, where a teacher has been pressured to stop teaching Between the World and Me because it made some students feel “ashamed to be Caucasian”; and the West Bank and East Jerusalem. It is in the last of these long, interconnected essays that Coates aims for the sort of paradigm shift that first earned him renown when he published “The Case for Reparations” in The Atlantic in 2014, in which he staked a claim for what is owed the American descendants of enslaved Africans. This time, he lays forth the case that the Israeli occupation is a moral crime, one that has been all but covered up by the West. He writes, “I don’t think I ever, in my life, felt the glare of racism burn stranger and more intense than in Israel.”

In This Issue

See All

Coates traveled to the region on a ten-day trip in the summer of 2023. “It was so emotional,” he told me. “I would dream about being back there for weeks.” He had known, of course, in an abstract sense, that Palestinians lived under occupation. But he had been told, by journalists he trusted and respected, that Israel was a democracy — “the only democracy in the Middle East.” He had also been told that the conflict was “complicated,” its history tortuous and contested, and, as he writes, “that a body of knowledge akin to computational mathematics was needed to comprehend it.” He was astonished by the plain truth of what he saw: the walls, checkpoints, and guns that everywhere hemmed in the lives of Palestinians; the clear tiers of citizenship between the first-class Jews and the second-class Palestinians; and the undisguised contempt with which the Israeli state treated the subjugated other. For Coates, the parallels with the Jim Crow South were obvious and immediate: Here, he writes, was a “world where separate and unequal was alive and well, where rule by the ballot for some and the bullet for others was policy.” And this world was made possible by his own country: “The pushing of Palestinians out of their homes had the specific imprimatur of the United States of America. Which means that it had my imprimatur.”

That it was complicated, he now understood, was “horseshyt.” “Complicated” was how people had described slavery and then segregation. “It’s complicated,” he said, “when you want to take something from somebody.”

How could he have been so wrong before? The fault lay partly with the profession he loved. In journalism, he had found his voice, his platform, his purpose in life. And yet, as he sees it, it was journalistic institutions that had not only failed to tell the truth about Israel and Palestine but had worked to conceal it. As a result, a fog had settled over the region, over its history and present, obscuring what anyone at closer range could apprehend easily with their own two eyes.

The Message is an attempt to use the journalist’s tools to dispel this veil. Coates was successful in such an effort before, when far fewer Americans understood the material grip that the legacy of slavery had on the descendants of the enslaved. In the years after “The Case for Reparations” was published, Coates was initiated into elite rooms in New York, Washington, and Hollywood. He testified before Congress, won a National Book Award, was interviewed by Oprah. This son of West Baltimore found himself, by his early 40s, an esteemed member of the powerful whose message was welcomed. And many are now eager for Coates to lend his considerable influence to the deadlocked public conversation on Israel and Palestine. But The Message also unquestionably breaks with the Establishment that championed Coates, risking his standing and possibly his career. Journalist Peter Beinart, a vocal critic of Israel, said, “Ta-Nehisi has a lot to lose.”

There are, of course, many who believe that the moral dimensions of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict are indeed complicated. The most famous of Israel’s foundational claims — that it was a necessary sanctuary for one of the world’s most oppressed peoples, who may not have survived without a state of their own — is at the root of this complication and undergirds the prevailing viewpoint of the political-media-entertainment nexus. It is Israel’s unique logic of existence that has provided a quantum of justice to the Israeli project in the eyes of Americans and others around the world, and it’s what separates Jewish Israelis from the white supremacists of the Jim Crow South, who had no justice on their side at all. But for Coates, one wrong cannot justify another. “All states at their core have a reason for existing — a moral story to tell,” he told me. “We certainly do. Does industrialized genocide entitle one to a state? No.” Especially, he said, at the expense of people who had no hand in the genocide.

What matters to Coates is not what will happen to his career now — to the script sales, invitations from the White House, his relationships with his former colleagues at The Atlantic and elsewhere. “I’m not worried,” he told me, shrugging his shoulders. “I have to do what I have to do. I’m sad, but I was so enraged. If I went over there and saw what I saw and didn’t write it, I am fukking worthless.”

At a checkpoint in the old city of Hebron. “I get sad every time I look at this photo,” Coates said. “This was the second day of the trip and the moment I realized how similar what I was seeing was to the world my parents and grandparents were born into.” Photo: Courtesy of Ta-Nehisi Coates

Coates is hardly the first person to attempt to elucidate the plight of the Palestinians. Then again, he was not the first person to tackle the subject of reparations, a staple of classroom discussions and political debate. “I remember when he told me he was writing ‘The Case for Reparations,’” said Chris Jackson, the editor of The Message and Coates’s other books. “I was like, ‘Ta-Nehisi, you can’t Columbus reparations.’” Even within The Atlantic, there was skepticism. “My first reaction was, This sounds nuts,” said Scott Stossel, Coates’s editor at the magazine. “This is a nonstarter.”

Coates, however, had the enthusiastic support of The Atlantic’s then–editor-in-chief, James Bennet. “He’s one of those writers you trust when he proposes an idea,” Bennet told me recently. “He’s really almost singular.” In one of several conversations we had after our breakfast in Gramercy, Coates recalled, “I couldn’t believe that I’m talking about this theoretical case for reparations and this white dude is like, ‘Okay, so how big can we do it?’” Coates had already won a National Magazine Award for his 2012 article “Fear of a Black President,” analyzing the racial paradoxes of Obama’s first term, which had earned him trust and leverage. And he had a blog where he was proving that there was an immense readership for topics that might seem off the news, the most prominent and surprising of which was the Civil War. “The groundwork was laid by building up the audience to field-test his ideas,” said Stossel. “And he had a lot of smart readers who would give him feedback. He starts out from a point of almost radical humility, where he is open to critiques from anyone.” Bennet told me, “He just constantly learned; he was a learning machine.”

Coates was obsessed with the historical narratives about the Civil War — how they’d been formed and how they overlaid the present. “It’s kind of hard to remember, but even as late as 2014, people were talking about the Civil War as this complicated subject,” Jackson said. “Ta-Nehisi was going to plantations and hanging out at Monticello and looking at all the primary documents and reading a thousand books, and it became clear that the idea of a ‘complicated’ narrative was ridiculous.” The Civil War was, Coates concluded, solely about the South’s desire to perpetuate slavery, and the subsequent attempts over the next century and a half to hide that simple fact betrayed, he believed, a bigger lie — the lie that America was a democracy, a mass delusion that he would later call “the Dream” in Between the World and Me.