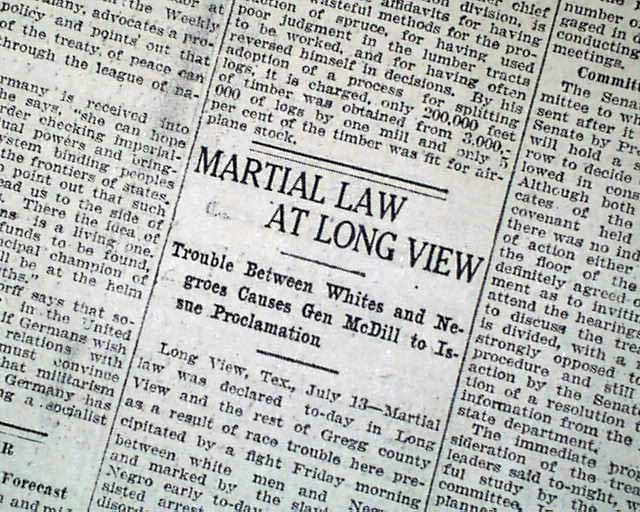

Riot

Storming of the jail

Sensing trouble, Knoxville police transferred Mayes from the small city jail on

Market Square to the larger

Knox County Jail on Hill Avenue. Knox County's

sheriff, W.T. Cate, then had Mayes transferred to

Chattanooga.

[1] By noon, news of the murder had spread, and a crowd of curious onlookers had gathered at the county jail, thinking Mayes was being held there.

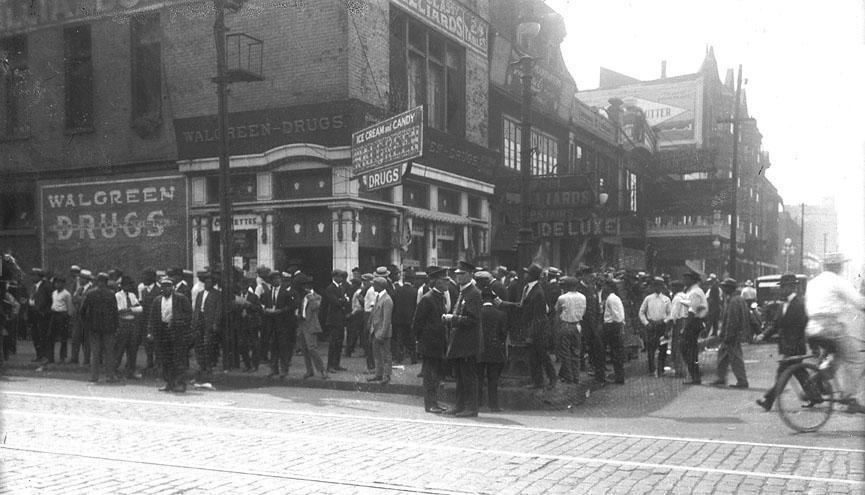

[1] A larger, angrier crowd had gathered on Market Square. By late afternoon, the crowd at Market Square had grown to about 5,000.

[1]

At 5:00 PM, the crowd at the jail became hostile, demanding Mayes be brought out. Deputy sheriff Carroll Cate (the sheriff's nephew) and jailer Earl Hall assured them Mayes was not there, and allowed several members of the crowd to inspect the jail.

[1] Jim Claiborne, an intoxicated member of this crowd, walked to Market Square and told the crowd there that Mayes was at the county jail, and that Cate and Hall were hiding him.

[1] Jim Dalton, a 72-year old iron worker, called for Mayes to be

lynched, and the 5,000-strong mob roared towards the jail.

[1]

Unable to convince the mob that Mayes was not in their custody, Cate and Hall locked the jail's riot doors. At about 8:30, the rioters

dynamited their way into the jail, ransacking it floor by floor in search of Mayes.

[1] They discovered and consumed a large portion of the jail's confiscated whiskey, and also stole as many firearms as they could find.

[1] They freed 16 white prisoners.

[3]

Two platoons of the

Tennessee National Guard's 4th Infantry, led by Adjutant General Edward Sweeney, arrived, but they were unable to halt the chaos.

[1]

Gun battle at Central and Vine

After

looting the jail and Sheriff Tate's house, the mob returned to Market Square, where they dispatched five truckloads of rioters to Chattanooga to find Mayes.

[1] General Sweeney, awaiting the arrival of reinforcements, pleaded with the rioters to disperse.

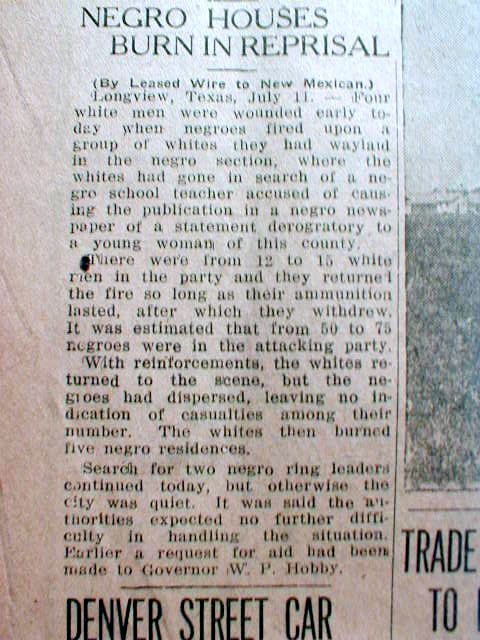

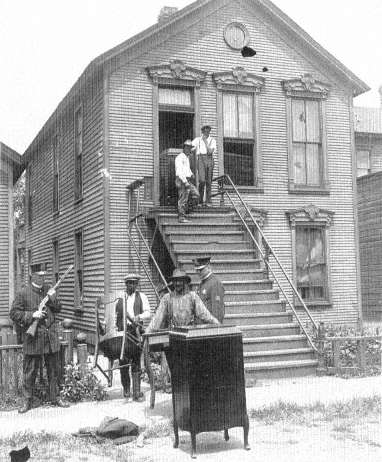

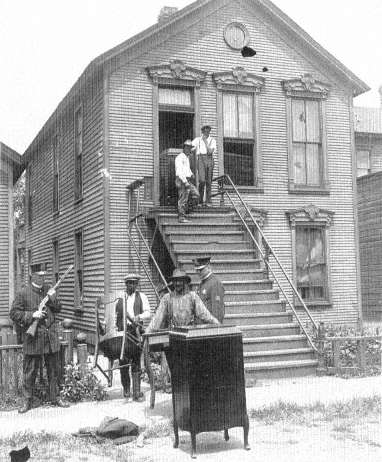

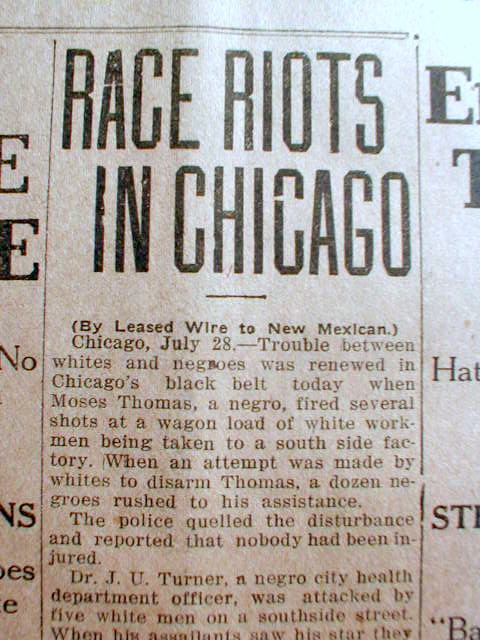

Meanwhile, many of the city's black residents, aware of the race riots that had occurred across the country that summer, had armed themselves, and had barricaded the intersection of Vine and Central to defend their businesses.[1]

As the trucks began to depart, shots rang out on Central, and it was falsely reported that two soldiers had been killed.

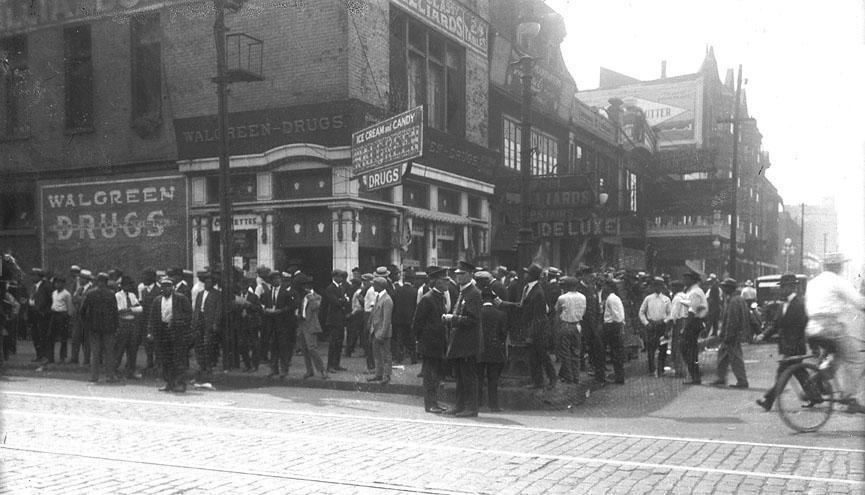

[1] Sweeney immediately ordered his guardsmen toward Vine, and the mob followed. Along the way, rioters broke into stores on

Gay Street to steal firearms and other weapons.

[5] As the guardsmen turned onto Vine, the street erupted in gunfire as black snipers exchanged fire with both the rioters and the soldiers.[1] The National Guard set up two Browning machine guns on Vine, and opened fire toward Central. One guardsman, 24-year-old Lieutenant James William Payne, was shot and wounded by a sniper, and as he staggered into the street, he was cut to pieces by friendly fire from the machine guns.[1]

Shooting continued sporadically for several hours. The black defenders charged the machine guns several times, but failed to capture them. Among those killed was a black shopkeeper and

Spanish-American War veteran named Joe Etter, who was shot when he attempted single-handedly to capture one of the machine guns.

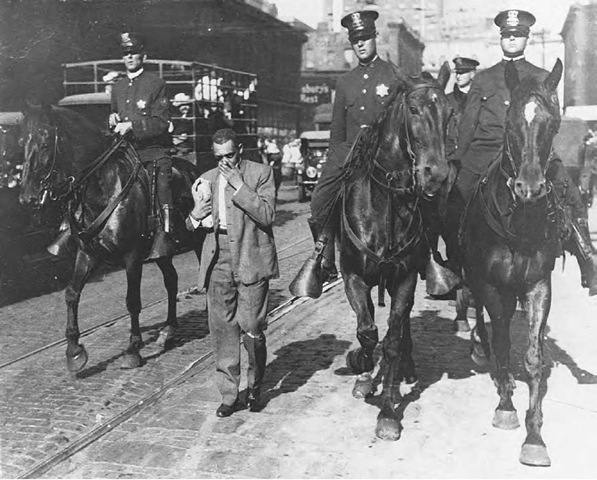

[1] Outgunned, the black defenders gradually fled Central and dispersed, allowing the guardsmen to gain control of Vine and Central in the early morning hours of August 31.

[1]

Walgreens was around back then? WOW

Walgreens was around back then? WOW