You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Essential The Official Contemporary Haitian Geopolitics/Event thread

- Thread starter Scientific Playa

- Start date

More options

Who Replied?loyola llothta

☭☭☭

Despite Jovenel’s Obstinance, Rival Opposition Committees Plan for his Departure

October 16, 2019

Eight of the nine members of the Consensual Alternative for the Refounding of Haiti’s “Commission for the Transfer of Power” tasked with planning “the immediate and orderly departure of Jovenel Moïse.”

What happens when the unstoppable force meets the immovable object? In Haiti, the answer seems to be: you form a commission.

As calls for and anticipation of Haitian President Jovenel Moïse’s resignation become universal in the face of an ever-growing and determined nationwide revolt, two opposition fronts have each rolled out their own “transition commission” to navigate the rocky road to a provisional government and, possibly, a new constitution.

Link:

Despite Jovenel’s Obstinance, Rival Opposition Committees Plan for his Departure | Haiti Liberte

October 16, 2019

Eight of the nine members of the Consensual Alternative for the Refounding of Haiti’s “Commission for the Transfer of Power” tasked with planning “the immediate and orderly departure of Jovenel Moïse.”

What happens when the unstoppable force meets the immovable object? In Haiti, the answer seems to be: you form a commission.

As calls for and anticipation of Haitian President Jovenel Moïse’s resignation become universal in the face of an ever-growing and determined nationwide revolt, two opposition fronts have each rolled out their own “transition commission” to navigate the rocky road to a provisional government and, possibly, a new constitution.

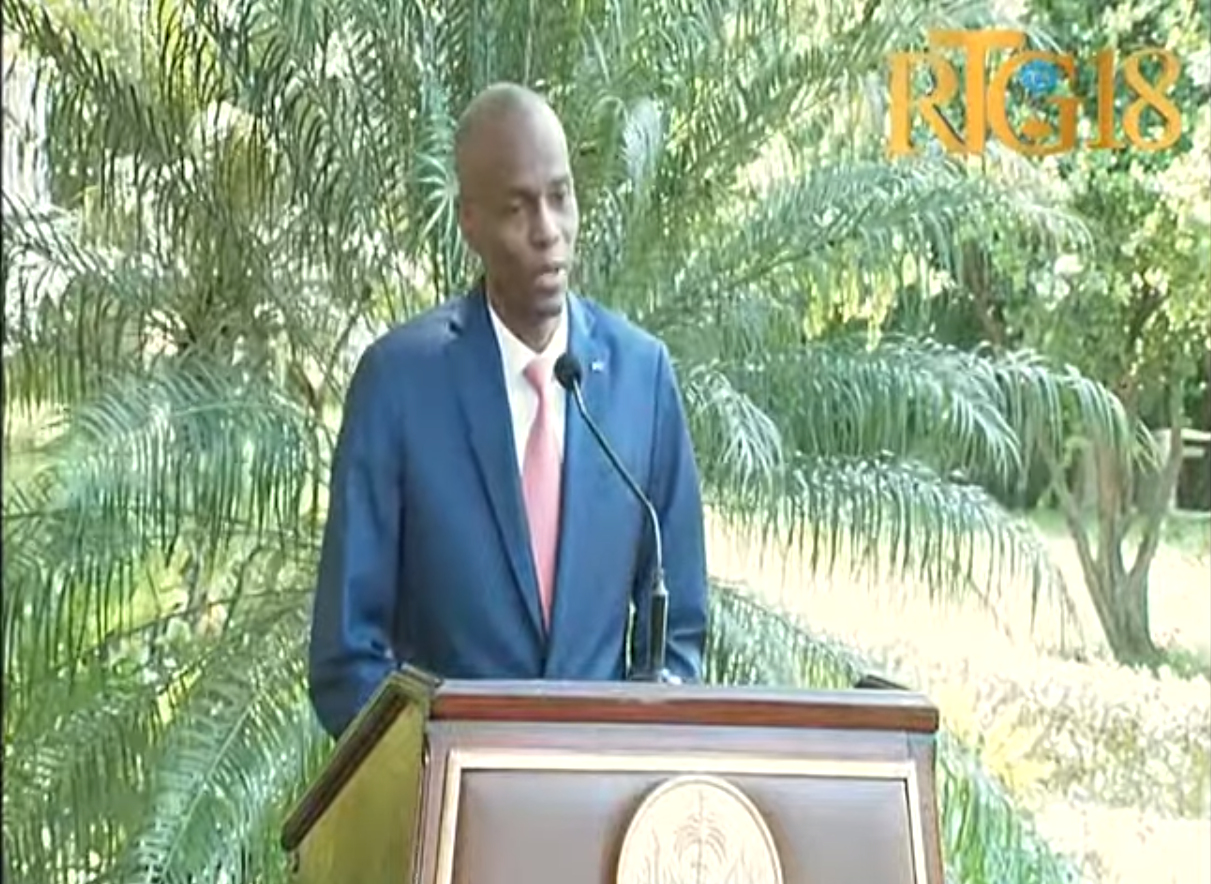

But, on Tue., Oct. 15, Moïse held a short outdoor press conference on the National Palace grounds to say that it would be “irresponsible” for him to step down. “Haiti doesn’t deserve this,” he said of the turmoil and misery gripping the country. “You voted for me to fight against a system,” he said, as if some unspecified “system” was responsible for Haiti’s woes, and he was fighting it.

On Oct. 15, President Jovenel Moïse gave an outdoor press conference, saying it would be “irresponsible” for him to resign.

His statement was reminiscent of “President-for-Life” Jean-Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier’s declaration one week before his flight from Haiti on Feb. 7, 1986 that he was holding onto power “as strong as a monkey’s tail.” That now famous phrase was the final provocation that spurred the Haitian masses to redouble their protests and send him packing.

On Thu. Oct. 10 at the Terrace Garden Villa on the capital’s Delmas 75 road, the Consensual Alternative for the Refounding of Haiti (an opposition front previously known as the Democratic and Popular Sector) presented a nine-member “Commission for the Transfer of Power,” tasked with planning “the immediate and orderly departure of Jovenel Moïse.” They would propose three judges from Haiti’s Court of Cassation (Supreme Court), one of whom would act as Haiti’s temporary President. He would choose a Prime Minister (which Haiti hasn’t had since March) and propose, to the Consensual Alternative’s signatories, a list of possible ministers for the “Transitional Government,” which would have up to three years to organize elections.

The members of the Commission are: long-time political activist and university professor Antoine “Tintin” Augustin; journalist and sociologist Antoinette Duclair, a member of the Petrochallenger coalition and of Solidarity with Haitian Consumers; Baby Doc’s former lawyer Gervais Charles; radio owner Michel Legros, Union of Popular Forces leader, and, previously, of the anti-Duvalierist Haitian League for the Implantation of Democracy (LHID); former musician and Pétionville mayor Claire Lydie Parent; Father Michel Frantz Grandois, vice-president of the Creole Academie and representative of the Forces of the Progressive Opposition (FOP); former Limonade Deputy Hugues Célestin, leader of the Marien Patriot Initiative (IPAM); writer Gary Victor, representing infamous businessman Réginald Boulos’ Movement for the Third Way party; and former Haitian Army Col. Himmler Rébu, the leader of the Grand Rally for the Evolution of Haiti party (GREH), who served as President Michel Martelly’s Sports Minister.

The Consensual Alternative’s commission was announced two days after the Moïse regime had named it own seven-member “Dialogue Commission” on Oct. 8, with the following members: Michel Martelly’s last Prime Minister Evans “K-Plim” Paul; the General Coordinator of the Office of Management and Human Resources Josué Pierre-Louis; Jovenel’s former Tourism Minister Emilie Jessy Menos; presidential advisor and former Borgne deputy Jude Charles Faustin; current Secretary General of the Council of Ministers Rénald Lubérice; Haitian Bald Headed Party (PHTK) president Sainphor Liné Balthazar; and former army officer, senator, and Martelly Defense Minister Jean Rodolphe Joazile.

At the call of Haiti’s musical artists, tens of thousands poured out on the capital’s Delmas Road on Oct. 13 to demand President Moïse’s resignation.

The regime’s commission was announced hours after Senate President and Jovenel ally Carl Murat Cantave issued a long, impassioned radio statement pleading that “dialogue is the one and only salvation for the resolution of our problems.” He called on President Moïse to put his mandate “on the table of dialogue, but also the mandates of elected officials of the Legislature and those of the Judiciary.”

The entire opposition rejected Moïse’s Dialogue Commission as too little, too late.

Finally, on Mon. Oct. 13, yet another transition shepherd was announced: the “Passerelle pour une transition” (Gateway for a Transition), a seven-member commission supposedly acting on behalf of 107 business, union, peasant, human rights, youth, and womens organizations which signed on to a “Joint Declaration for a National Rescue Government.”

The new front is ominously headed by perennial Washington ally and Episcopal Church Bishop Edouard Paultre, who is also the coordinator of the Haitian Council of Non-State Actors (CONHANE). The “Gateway for a Transition” and the Joint Declaration’s assemblage appear to be dominated by Haiti’s bourgeoisie and its business associations – Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Haiti (CCIH), Haiti Industries Association (ADIH), American Chamber of Commerce (AMCHAM), the Franco-Haitian Chamber of Commerce and Industry (CFHCI), and several regional chambers of commerce and industry.

The “National Rescue” front may be a spin-off of or merger with the Patriotic Forum of Papay, the Consensual Alternative’s previous opposition rival. The “National Rescue” counts among its 107 signatories Chavannes Jean-Baptiste’s Peasant Movement of Papay (MPP) and the National Peasant Movement of the Papay Congress (MPNKP) – also known as 4 G Kontre (Four Eyes Meet) – as well as Tèt Kole Ti Peyizan Ayisyen (Heads Together of Small Haitian Peasants), founded by the assassinated Father Jean-Marie Vincent. Chavannes’ cluster of organizations were the host and central organizer of the Aug. 27-31 conference which gave birth to the Patriotic Forum front.

The “National Rescue” front is clearly the new opposition heavy-weight, not just due to the leading role of Paultre and the bourgeoisie, but also the adherence of 51 unions, including the strategic transport and drivers syndicates, key to any general strike.

The seven “Gateway for a Transition” members are: businessman and CCIH president Frantz Bernard Craan, singer Carole Demesmin, authors Castel Germeil and Dr. Charles Manigat, university professors Sabine Manigat and Lemète Zéphyr, and Dr. Sofia Loréus.

In their declaration, the “National Rescue” front calls on Moïse and the Parliament to resign, for the restoration of public order, administration, and services, an “emergency program” for the “vulnerable” poor, “revival of economic activities… Putting public finances in order… Follow-up on records related to the management of Petro Caribe funds and other matters related to corruption and misappropriation of public property… Reorganization of the Electoral Council… Organization of a National Conference… Preparation and voting of a new constitution… Reform of the justice system” aimed at ending “the culture of impunity,” among other things. The group did not specify the details of how it saw the transition taking place or its goals being achieved.

Meanwhile, after over 15 years of deployment, the last United Nations “peace-keepers” finally left Haiti on Oct. 15. The unarmed United Nations Integrated Office in Haiti (UNHIN or, in French, BINUH) replaced the 1,300-police officer United Nations Mission to Support Justice in Haiti (MINUJUSTH). The Special Representative of the UN Secretary-General held over from MINUJUSTH to head UNHIN is Helen Meagher La Lime, a former career U.S. State Department officer who was most recently U.S. Ambassador to Angola (2014-2017) before joining the UN. La Lime is the first former U.S. diplomat to head UN missions in Haiti.

UNHIN chief Helen Meagher La Lime with UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres last year. Credit: UN Photo

UNHIN has a one-year mandate to advise the Haitian government on ways to “promote and strengthen stability and good governance” and “to support the government in the areas of elections, police, human rights, prison administration, and justice system reform.”

Add to this explosive cocktail the growing size and ferocity of Haiti’s anti-Jovenel demonstrations. Marches, skirmishes, injuries, and deaths are occurring in towns around the country, but the largest actions are in and around Port-au-Prince, the capital.

On Fri. Oct. 11, marching protestors aimed to reach Moïse at his mountain home in Pèlerin 5 in order to “retrieve his resignation letter,” they said. This led to pitched battles en route in the upscale town of Pétionville between the police and demonstrators. Some protestors tried unsuccessfully to set fire to the fancy Kinam Hotel on the central square, St. Pierre Place.

Then, two days later, on Sun. Oct. 13, a giant multitude of tens of thousands turned out on the capital’s Delmas Road for a protest organized by Haiti’s musical artists. That demonstration’s tremendous size marked a new high-water mark for the popular tide relentlessly rising around the regime.

Link:

Despite Jovenel’s Obstinance, Rival Opposition Committees Plan for his Departure | Haiti Liberte

loyola llothta

☭☭☭

Historic Iron Market in #Haiti - a symbol of sovereignty,

where small-scale entrepreneurs sold their goods and services and made a good living. Like many others, it was mysteriously burned down last year. The Best Western Hotel, on the other hand, paid $4 per day before taxes.

loyola llothta

☭☭☭

22 October 2019

Haiti’s Endless Sorrows

By Stephen Lendman

Few people anywhere have suffered as long and egregiously as Haitians.

No strangers to adversity and anguish, for over 500 years, they endured severe oppression, slavery, despotism, colonization, reparations, embargoes, sanctions, deep poverty, starvation, unrepayable debt, and natural calamities.

Except for brief interregnum periods, most recently under priest, educator, man of the people-turned politician Jean-Bertrand Aristide in the 1990s and early new millennium years, Haitian misery continues unabated.

Toppled twice by US regimes — by Bush I in 1991, again in 2004 Bush II/Cheney, Aristide no longer is involved in Haitian politics. Widespread suffering has gone on for time immemorial.

Today Haitians are enduring some of their worst ever oppression, misrule, and deprivation under US puppet Jovenel Moise since installed in February 2017.

Protests for his removal raged almost daily since July 2018. Countless thousands of long-suffering Haitians have demonstrated in the capital Port-au-Prince and other cities nationwide.

They demand Moise’s resignation, installation of a transitional government, repeal of increased gasoline and other punitive taxes, as well as against regime corruption and oppression.

On Monday, Liberation News called Haiti’s landscape “apocalyptic, reflecting the fierce class war that has been waged since (summer 2018), if not for decades,” adding:

“The huge crowds are heroically taking to the streets to defend Haitian sovereignty from the murderous military forces and corrupt, corporate interests that dominate the Haitian government.”

“With each passing day and week, the movement only continues to grow in size and strength” — despite brutal regime violence, other human rights abuses, and indifference to popular needs and rights.

Police consistently attack protesters with tear gas, water cannons, beatings, and live fire, killing around 20 in recent weeks, arresting and injuring countless others.

Brutality failed to deter justifiable public rage over intolerable conditions, including deep poverty, lack of vital public services, unaffordability of food and other essentials to life, along with grand theft by Moise, other regime officials and cronies.

Haiti is indebted to the IMF and World Bank loan sharks of last resort, demanding their pound of flesh, compelling indebted nations to erode social services so they, private bankers and other corporate predators are paid, ordinary people exploited to serve them.

Haitians mostly suffer from longstanding US imperial control, plundering the country and exploiting its people for profit, no matter the human toll.

It’s what Chicago School fundamentalism is all about, featuring free-wheeling capitalism, unrestrained profit-making, public wealth in private hands, minimal (if any) social services, government serving powerful interests exclusively, human rights and needs ignored, along with harsh crackdowns on critics.

Haiti is the region’s poorest country, most of its people struggling on less than $2 a day to survive, enduring hunger, malnutrition, overall deprivation, and repressive rule.

Moise is Washington’s man in Port-au-Prince.

Reviled by Haitians, protests continue to replace him.

Opposition elements formed so-called transition commissions, wanting him replaced with provisional rule, possibly a new constitution.

Falsely claiming it would be “irresponsible” for him to resign, his days may be numbered, dark forces in Washington perhaps wanting a clean slate with new puppet rule to try assuaging public rage.

No matter who’s in charge internally, US grip on the country is firm. Earlier in October, Haiti Liberte reported that anti-Moise protests continue with no signs of abating.

They’ve partially or entirely shut down Port-au-Prince, burning barricades, disrupting commerce, and weakening Moise’s hold on power.

Millions of Haitians won’t be deterred until he’s gone — what replaces him likely to be continued dirty business as usual like most always before.

Last week, Haiti Liberte editor Kim Ives reported that UN blue helmet MINUSTAH forces ended 15 years of repressive post-Aristide occupation on October 15.

They’re replaced by the so-called UN Integrated Office in Haiti (UNHIN), headed by Helen La Lime, a career State Department official, serving US imperial interests.

Ives explained that

“UNHIN has a one-year mandate to advise the Haitian government on ways to ‘promote and strengthen stability and good governance (and) support the government in the areas of elections, police, human rights, prison administration, and justice system reform.”

Like nearly always before, when things change in Haiti and other US-controlled countries, everything stays the same under new faces, continuing exploitation and repression.

Link:

Haiti’s Endless Sorrows - Global Research

loyola llothta

☭☭☭

Friday, September 20, 2019

Fighting for September 20 to be Jean-Jacques Dessalines National Holiday

To this day, Haiti has as a national holiday October 17 to celebrate the founder of the nation, Jean-Jacques Dessalines. But along with a recent awakening of Dessalinienne ideals, the push is being made to have September 20 become the national holiday to celebrate the emperor.

Link:

Fighting for September 20 to be Jean-Jacques Dessalines National Holiday

Fighting for September 20 to be Jean-Jacques Dessalines National Holiday

To this day, Haiti has as a national holiday October 17 to celebrate the founder of the nation, Jean-Jacques Dessalines. But along with a recent awakening of Dessalinienne ideals, the push is being made to have September 20 become the national holiday to celebrate the emperor.

The movement is being led by Bayyinah Bello, a historian who directs the Marie Claire Heureuse Félicité Bonheur Dessalines Foundation, named after the wife of Jean-Jacques Dessalines.

Because October 17, 1806 is the day Dessalines was assassinated, it has never made sense that this would be the day celebrated. That the event of his assassination would be a full-fledged national holiday. That the assassins and their act, be remembered in honorary fashion for all history.

This is the position of Bayyinah Bello and many others, including us here at The Haiti Sentinel, that support the change being made into law.

The President of the Republic has the power to decree a day of rememberanc, holiday, or closing of national offices. But to institute a national holiday that will be kept nationwide, through all the territories, departments and municipalities, it will take an act of the legislature, the Parliament.

Link:

Fighting for September 20 to be Jean-Jacques Dessalines National Holiday

loyola llothta

☭☭☭

loyola llothta

☭☭☭

loyola llothta

☭☭☭

Seem like Taiwan got word the haiti government is trying to leave them .. So the next step is to cry to the core group to stop them. lol man fuk Taiwan want be cacs

Taiwan dont know who they fuking with. All Taiwan shyt can get burn down let them keep playing around

loyola llothta

☭☭☭

The poor in #Haiti can't catch a break with the neocolonial oligarchy. CIA linked, coup-plotting, death squad financier @ReginaldBoulos [Reginal Boulos] who conspired with Hillary Clinton to steal Haiti's 2010 and 2015 presidential elections will run for president in 2022.