source=some random british site

When I first set out to meet

Manu Chao in 2001, I had been told the man I was looking for had a small pied à terre in Barcelona with no outside space, because the "street is my courtyard". He could, when in town, be found busking in his local bar. He owned bees but no mobile phone or watch. He was always on the move, addicted to travel, never able to spend more than a few weeks in the same place, never planning more than three months ahead. He was – as the line had it on one of his songs,

Desaparecido – "the disappearing one ... hurry[ing] down the lost highway ... When they look for me I'm not there, When they find me, I'm elsewhere".

I couldn't complain I hadn't been warned. But nor could I resist the impulse.

Like so many others, I had sensed on

Clandestino, Manu's first solo album, a passion and directness the like of which I hadn't come across since Bob Marley. It was released 15 years ago, a year after the Buena Vista Social Club album, that sepia-tinted homage to Cuban

son. Both records effectively kicked off the "world music" boom, although it's a label Manu has always rejected, even as he benefited from it.

Clandestino seemed to look both backwards to a time when songs meant something, when people thought music could change the world, and forwards to a new globalised pop. At the cross-fade of the millennium, it sounded perfect – a radical masterpiece, on the side of the dispossessed and immigrants, that united, irresistibly, a European and South American perspective.

If I'd been more up to speed on French music, I would have been less surprised. Manu Chao's previous outfit,

Mano Negra, had been the biggest band in the history of Gallic rock, with legions of followers in Europe and in South America, where they still have a mythic status. When asked the meaning of anarchy on Argentinian TV, they trashed the studio, and woke up famous.

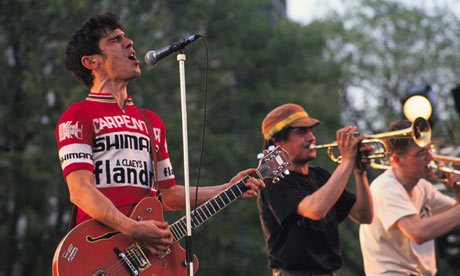

Manu Chao with La Mano Negra in Nantes, France, 1991. Photograph: Alain Le Bot/Gamma-Rapho/Getty Images

Plenty of people agree with their manager Bernard Batzen when he claims that had the band actually promoted their albums properly, instead of embarking on quixotic missions such as a four-month boat trip around Latin America, or a rail trip through the guerrilla chaos of Columbia in 1992 (described at the time as "less like a rock'n'roll tour, more like Napoleon's retreat from Moscow"), they would have been as big as U2 or Coldplay.

But Mano Negra broke up, bitterly, before their best-selling album

Casa Babylon was even released. The group had been set up as a democracy but Manu was the singer, songwriter and the artistic visionary, and eventually the tension became too great. The others turned on Manu, and when they refused to let him keep the name Mano Negra to use for another outfit, he thought his career was over. And he had also split up with his long-term girlfriend. He spent the next three years on an extended "lost weekend", pinballing around the world, traveling throughout South America and to west Africa, depressed and often suicidal. ("A cow saved my life," he later said, impressed by the compassion in the beast's eyes when it wandered into a beer shack in a Rio favela when he was at rock bottom.)

For three years, between 1992 and 1995, he was missing-in-action, a nomad playing the bars of Rio and Tijuana, experimenting with peyote in Mexico City, entertaining the children of insurgents in Chiapas in Mexico. (A supporter of the Zapatistas, he went on to sample the voice of the charismatic activist Subcommandante Marcos on Clandestino). Only following a motorbike ride from Paris to the greenness of Galicia with his father, the writer Ramon Chao, did he slowly return to sanity. "I had a bad addiction to travel," he later told me. But all the time, he had also been writing songs.

"Clandestino was the result of that time," he said. "I didn't know I was making a record. It was pure therapy."

Back in Paris he met a sympathetic musical co-pilot called

Renaud Letang, and the duo sifted through scores of songs before settling on the tracks that became Clandestino. Manu at the time was fascinated by electronica, and the first version was heavy with dance beats. But one day, Letang's computer got a bug which stripped out most of the electronics and drums, leaving the music spare, naked and beautiful, like an old painting cleaned of years of dirt to reveal a masterpiece. "Le hazard est mon ami" he likes to say – chance is his friend. They tried different different mixes on the children, aged three and six, who lived next door. "The ones they liked were the ones we chose," Manu recalled.

The duo felt they were on to something but it didn't sound like anything they had heard before. "We felt we had given birth to a UFO," as Letang put it. Most music professionals thought the album would sell a few thousand to Mano Negra fans, although its lack of rock energy might alienate them. There was no band to promote the album, it didn't fit into radio station formats, and mainstream broadcasters used the drugs references on tracks like Welcome to Tijuana as an excuse not to play it.

Manu felt it was his swansong, and it initially looked that way, reaching No 19 in the French charts before it stalled. But Virgin's low-key marketing of the album, with its anti-consumerist aura, let fans discover it for themselves. It initially became the soundtrack of choice for backpackers in hip beach destinations like Koh Samui in Thailand and Puerto Escondido in Mexico – its bitter-sweet quality perfect for the moment the sun goes down. A full year after its release, it entered the French Top 10 and then stayed in the charts for the next four years. In Europe (albeit not the UK, not quite) and in South America, it became seen as a classic – selling more than five million copies (and probably the same again if you count the pirated versions).

Once this triumph became finally apparent, Virgin committed to the follow up,

Proxima Estacion - Esperanza, and Manu assembled a crack band. Almost immediately they played to a crowd of over 100,000 in Mexico City. As he had promised himself he would if he ever had the chance to "use the microphone" again, he leveraged his fame to promote certain cherished causes. He publicised fights against water privatisation in Bolivia, supported community radio stations in Argentina and became one of the best known opponents of globalisation at the G8 meeting in Genoa in 2001 – even though he always insisted "there's nothing so corrupt as to be a leader".

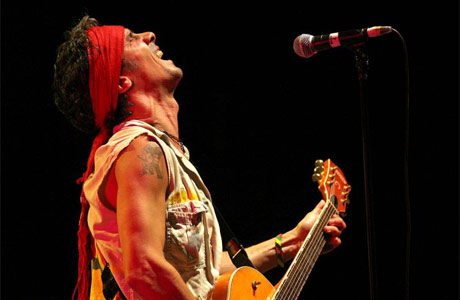

Manu Chao at the Brixton Academy in 2007. Photograph: Rex Features

When it came to writing my book on Manu, it was the chance to talk about some of these issues that sold the idea to him – rather than the prospect of a conventional rock biog. In fact, it ended up as two books in one – the first his back story, through the alternative bands in Paris, followed by explosive success, those insane boat and train tours and his breakdown and lost years. Then it picks up when I meet him in 2001 and takes in adventures at a psychiatric asylum in Buenos Aires, where Manu recorded with the inmates; in Mexico, where gigs were cancelled due to drug gang outrages; in Madrid, with prostitute activists; and in the Sahara at a refugee camp, where I ended up playing bongos with the actor Javier Bardem. I tried to find Manu in Brazil and Galicia and failed.

Following Proxima Estacion-Esperanza there came

La Radiolina in 2007, but a couple of live albums and his work with the Malian duo Amadou & Mariam aside, there has been little else – although hours' worth of unreleased music is known to exist. Even after all this time, Manu Chao is still elusive, still the "desaparecido", hurrying down the lost highway.

Peter Culshaw's book Clandestino: In Search Of Manu Chao is published by Serpent's Tail