This market doesn’t make any sense. I think it’s just rich people and hedge funds sitting on inventory. Nobody can afford these prices and the people that are buying are getting fukked in the long term. Low rates won’t save you, prices need to fall at least a quarter.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The housing market just slid into a full-blown correction

- Thread starter OfTheCross

- Start date

More options

Who Replied?ADevilYouKhow

Rhyme Reason

I must’ve missed the full blown correction

You'd think REITs would be making some money here, but they haven't had much good performance in 2024

ogc163

Superstar

I remember a time back in 2017, when I was at a friend’s dinner party. He mentioned that one of the other guests was a housing activist, and that because I was also interested in housing issues, she and I should talk. The activist asked me what I thought we needed to do to ensure affordable housing in San Francisco, to which I responded “We should let people build a lot more of it.” At which point a look of shock and dismay came over her face, and in a horrified voice she asked: “Market rate??”

“Yes,” I said. “Market rate.”

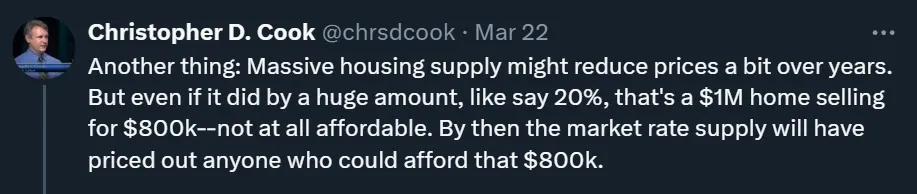

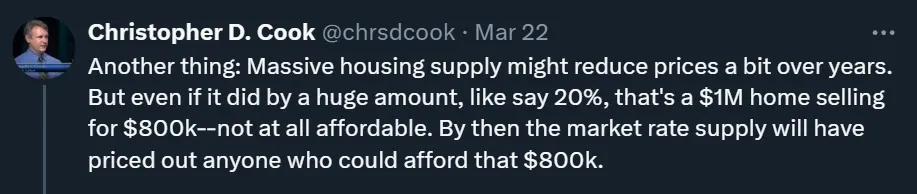

In fact, the belief that building market-rate housing raises rents is surprisingly common. For example, independent journalist Christopher Cook recently tweeted:

And Calvin Welch of 48Hills declares:

As for Welch, it’s not clear what sort of “definition” he thinks he’s referencing here. I don’t want to put words into his mouth, but it seems as if he thinks that the price of a market-rate rental unit comes built into its walls and floors — that market rents in an expensive city are fixed, and have nothing to do with the number of units that exist there.

Whatever the reasoning here, though, what clearly comes through is a deep-seated antipathy toward market-rate housing — the same antipathy that I encountered at my friend’s dinner party. This antipathy is misplaced. Though building market-rate housing won’t always be enough to solve a city’s housing problems all by itself, it’s an important part of any affordable housing policy.

How market-rate housing makes cities more affordable

Cities like San Francisco and NYC have various policies to make housing more affordable. One example is rent control. Another is inclusionary zoning, which mandates that the people who own a rental property offer some percent of the units for a discount. These are all types of price controls.

Because some units in a modern American city are price-controlled, it means that market-rate units will usually be more expensive than the average unit. This isn’t always 100% true — some market-rate units might be even cheaper than price-controlled units because they’re really small and crappy, or because they’re in a really dangerous neighborhood, etc. But in general, market-rate units will be more expensive than the average unit.

So it’s easy to see how building more market-rate housing can increase average rents. The key word here is “average”. Think about a city where everyone owns a Honda Civic, which sells for $26,000. And then you build a Lamborghini and offer it for sale in that city for $300,000. Maybe some rich person ditches their Civic for the Lambo, or maybe some rich person moves into the city and buys the Lambo. Either way, the average price of cars in the city has gone up, since now there’s an expensive Lamborghini in the average.

But did building the Lambo make cars in the city less affordable? No, it didn’t! A Civic still costs $26,000. There are still the same number of Civics, so everyone can still get a $26,000 Civic if they want one. No one is being forced to pay more for a car than they were before the Lambo was built. The rise in the average price of a car is purely a statistical quirk.

In fact, the arrival of the Lambo will probably make cars more affordable in this city. If one rich person ditches their Civic to buy the Lambo, that means there’s one more Civic on the market in this town. Suppose the town starts with 10,000 people, each with a Civic. Then after the richest person puts their Civic on the market, you now have 9,999 people and 10,000 Civics. That means the price of a Civic will go down — whoever’s selling that extra Civic will have to offer it at below $26,000, to get someone to buy it as their second car. That price cut will lower the average price of Civics in this town.

Ta da! Building an expensive car made cars in general more affordable.

This is exactly how building market-rate housing — even fancy “luxury” market-rate housing — makes housing more affordable in general. Suppose you bulldoze a parking lot in San Francisco and build a gleaming new tower full of market-rate apartments targeted at tech workers. Maybe some tech workers move in from San Jose or Palo Alto to live in those apartments — but probably not, since their jobs are down in San Jose and Palo Alto. More likely, they move into the gleaming new market-rate units from other parts of San Francisco. They move from low-rises in the Mission and Bernal Heights, from old Victorians in the Haight, and so on.

And when the tech workers move to the new tower, what happens to those rental units they just vacated? Those units go on the market! And unless landlords want to let their units sit vacant for many months (which costs them a lot of money), they have to rent those units at a discount to whatever they were charging before.

Who moves into those newly discounted units? Maybe some other tech yuppies looking for a bargain. Maybe some service workers paying market rent in the East Bay and commuting over every day to work in SF. Maybe some middle-class family currently paying market rent elsewhere in SF. It’s not clear.

But whoever it is, the availability of a discounted market-rate unit gives them some negotiating leverage with their current landlord. They can now say “Oh hey, landlord. That discounted market-rate unit just opened up across town and I’m thinking about moving there. But I’ll stay here if you cut my rent a little bit.” Their current landlord now has an incentive to cut their rent a little bit, in order to avoid having their unit go vacant.

So by this process, building fancy new expensive market-rate housing lowers rents for regular folks.

This process is especially important when you have a city that’s attracting a big influence of highly-paid people looking for rental units (i.e., yuppies). Without any new market-rate construction, the yuppies will flood into the city’s older housing stock, offering to throw wads of cash at landlords for the chance to move into a low-rise or an old SF Victorian or a Brooklyn brownstone or whatever. By building gleaming new towers of fancy “luxury” units, you can divert those yuppies, so that they don’t start a bidding war with existing middle-class residents for existing middle-class units.

I explained this in one of my favorite old posts, in which I called the towers “yuppie fishtanks”:

“Yes,” I said. “Market rate.”

In fact, the belief that building market-rate housing raises rents is surprisingly common. For example, independent journalist Christopher Cook recently tweeted:

And Calvin Welch of 48Hills declares:

The logic behind these posts isn’t immediately clear. For example, Cook seems to be concerned mainly with the price of buying a house. But “affordable housing” policies, like inclusionary zoning, rent control, and public housing, are all about renting houses (unless you’re in Singapore, but we’ll talk about that later). When Cook calls for “affordable housing projects” and “supportive housing for homeless people”, he’s talking about rental units. Those projects will do nothing to bring down the $800k home purchase price he complains about.By definition an affordable housing crisis cannot be solved by the market for the simple reason that the folks needing the housing are simply priced out of the market.

As for Welch, it’s not clear what sort of “definition” he thinks he’s referencing here. I don’t want to put words into his mouth, but it seems as if he thinks that the price of a market-rate rental unit comes built into its walls and floors — that market rents in an expensive city are fixed, and have nothing to do with the number of units that exist there.

Whatever the reasoning here, though, what clearly comes through is a deep-seated antipathy toward market-rate housing — the same antipathy that I encountered at my friend’s dinner party. This antipathy is misplaced. Though building market-rate housing won’t always be enough to solve a city’s housing problems all by itself, it’s an important part of any affordable housing policy.

How market-rate housing makes cities more affordable

Cities like San Francisco and NYC have various policies to make housing more affordable. One example is rent control. Another is inclusionary zoning, which mandates that the people who own a rental property offer some percent of the units for a discount. These are all types of price controls.Because some units in a modern American city are price-controlled, it means that market-rate units will usually be more expensive than the average unit. This isn’t always 100% true — some market-rate units might be even cheaper than price-controlled units because they’re really small and crappy, or because they’re in a really dangerous neighborhood, etc. But in general, market-rate units will be more expensive than the average unit.

So it’s easy to see how building more market-rate housing can increase average rents. The key word here is “average”. Think about a city where everyone owns a Honda Civic, which sells for $26,000. And then you build a Lamborghini and offer it for sale in that city for $300,000. Maybe some rich person ditches their Civic for the Lambo, or maybe some rich person moves into the city and buys the Lambo. Either way, the average price of cars in the city has gone up, since now there’s an expensive Lamborghini in the average.

But did building the Lambo make cars in the city less affordable? No, it didn’t! A Civic still costs $26,000. There are still the same number of Civics, so everyone can still get a $26,000 Civic if they want one. No one is being forced to pay more for a car than they were before the Lambo was built. The rise in the average price of a car is purely a statistical quirk.

In fact, the arrival of the Lambo will probably make cars more affordable in this city. If one rich person ditches their Civic to buy the Lambo, that means there’s one more Civic on the market in this town. Suppose the town starts with 10,000 people, each with a Civic. Then after the richest person puts their Civic on the market, you now have 9,999 people and 10,000 Civics. That means the price of a Civic will go down — whoever’s selling that extra Civic will have to offer it at below $26,000, to get someone to buy it as their second car. That price cut will lower the average price of Civics in this town.

Ta da! Building an expensive car made cars in general more affordable.

This is exactly how building market-rate housing — even fancy “luxury” market-rate housing — makes housing more affordable in general. Suppose you bulldoze a parking lot in San Francisco and build a gleaming new tower full of market-rate apartments targeted at tech workers. Maybe some tech workers move in from San Jose or Palo Alto to live in those apartments — but probably not, since their jobs are down in San Jose and Palo Alto. More likely, they move into the gleaming new market-rate units from other parts of San Francisco. They move from low-rises in the Mission and Bernal Heights, from old Victorians in the Haight, and so on.

And when the tech workers move to the new tower, what happens to those rental units they just vacated? Those units go on the market! And unless landlords want to let their units sit vacant for many months (which costs them a lot of money), they have to rent those units at a discount to whatever they were charging before.

Who moves into those newly discounted units? Maybe some other tech yuppies looking for a bargain. Maybe some service workers paying market rent in the East Bay and commuting over every day to work in SF. Maybe some middle-class family currently paying market rent elsewhere in SF. It’s not clear.

But whoever it is, the availability of a discounted market-rate unit gives them some negotiating leverage with their current landlord. They can now say “Oh hey, landlord. That discounted market-rate unit just opened up across town and I’m thinking about moving there. But I’ll stay here if you cut my rent a little bit.” Their current landlord now has an incentive to cut their rent a little bit, in order to avoid having their unit go vacant.

So by this process, building fancy new expensive market-rate housing lowers rents for regular folks.

This process is especially important when you have a city that’s attracting a big influence of highly-paid people looking for rental units (i.e., yuppies). Without any new market-rate construction, the yuppies will flood into the city’s older housing stock, offering to throw wads of cash at landlords for the chance to move into a low-rise or an old SF Victorian or a Brooklyn brownstone or whatever. By building gleaming new towers of fancy “luxury” units, you can divert those yuppies, so that they don’t start a bidding war with existing middle-class residents for existing middle-class units.

I explained this in one of my favorite old posts, in which I called the towers “yuppie fishtanks”:

ogc163

Superstar

Rest of the article...