By AFRICA REVIEW TEAM

More by this Author

When Nigeria’s President Muhammadu Buhari recently announced that he and his deputy would take a pay cut, it was not entirely surprising for a man known for his austerity, and who faces a challenge cutting back the excesses in the country’s finances.

But President Buhari is not the first African leader to announce a pay cut. In fact, it is a popular recourse for others trying to shore up their popularity, or facing tough economic times.

In Kenya, President Uhuru Kenyatta and his deputy William Ruto last year announced a voluntary 20 per cent salary cut and invited other top government officials to follow suit. A few did, reluctantly.

In Tunisia, former President Moncef Marzouki, then facing an economic crisis in the post-revolution period, announced a two-thirds pay cut, slicing his annual pay from around $176,868 (Ksh 17m) to ‘just’ $58,956 (Ksh5.8m).

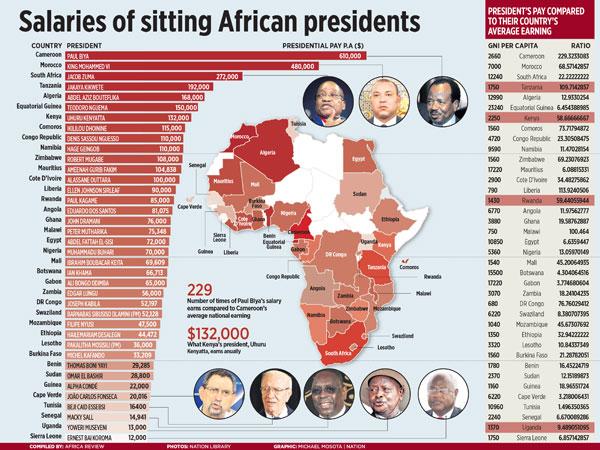

The Africa Review has compiled and analysed salaries of African leaders to try and see what they tell about the relationship between those in power and the governed. The search shows that only a few countries make public what they pay their leaders – a key finding itself that suggests a lack of transparency.

In many African countries, the first thing leaders do when they come into power is to increase their pay: In Egypt, for instance, the president’s pay shot up from a paltry $280 per month, put in place by the austere Mohammed Morsy administration, to $5,900 (Ksh584,000) per month just before General Abdel Fattah al-Sisi predictably won election.

In other countries, leaders take a disproportionate share of the national income for their personal use. In Morocco, the Treasury spends, by one account, $1 million a day on King Mohammed VI’s 12 royal palaces and 30 private residences. That is on top of $7.7 million spent on an entourage of royal automobiles, and a monthly salary of $40,000 (Ksh4m) paid to the monarch.

In 2014, King Mswati of Swaziland increased his personal budget, which includes his salary and the welfare of his extensive family, by 10 per cent to $61 million, a significant chunk of the kingdom’s overall budget. As the royal budget isn’t debated or passed by Parliament, it automatically became law.

Some presidents have deceptively small salaries but have, personally or through family members, massive control over their countries’ resources.

For example, President Eduardo dos Santos has a modest monthly salary of $5,000 (Ksh500,000) but is widely believed to control a lot of the wealth produced from Angola’s oil-industry, and his family members own some of the biggest enterprises in the country.

The Africa Review was unable to establish the official salary for Teodoro Obiang’ Nguema Mbasogo, the long-serving president of the oil-rich Equatorial Guinea, but it probably doesn’t matter.

With vast oil wealth and a population of less than a million, Equatorial Guinea has one of the highest per capita incomes in the world and should be a first-world nation. Instead, most of its wealth ends up in the hands of its notoriously corrupt First Family.

As an example, the US Department of Justice, in an indictment of the younger Teodoro Nguema Obiang’ Mangue, said the first son had spent about $315 million on property and luxury goods between 2004 and 2011, despite his job as a government minister paying less than $100,000 per year.

However, not all African leaders are money-grabbing, power-hungry brutes. In April 2015 Cape Verde President João Carlos Fonseca vetoed – for the fourth time, no less – a Bill that would, among other things, have increased his salary and that of other political officials.

The highest-paid leader, the research could find, is Paul Biya, whose $610,000 (Ksh61m) annual salary is almost three times that of South Africa’s Jacob Zuma, despite the South African economy being 10 times bigger than Cameroon’s.

Rather than simply rank the leaders based on absolute figures, The Africa Review decided to compare their gross annual salaries with the Gross National Income of their countries – basically comparing the leader’s pay with what their nationals, on average, earn.

Unsurprisingly, President Biya comes out on top again, earning 229 times what an average Cameroonian earns, followed by Liberia where President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf earns 113 times what her average citizen does.

Although Somalia’s President Hassan Sheikh Mohamoud makes the top 10 with his annual salary of $120,000 (Ksh12m), the country is excluded from the comparative study due to the lack of verifiable GNI per capita figures.

Overall, it appears that leaders of poor countries tend to pay themselves more than those in higher-income countries.

In Summary

- In Kenya, President Uhuru Kenyatta and his deputy William Ruto last year announced a voluntary 20 per cent salary cut and invited other top government officials to follow suit. A few did, reluctantly.

- In 2014, King Mswati of Swaziland increased his personal budget, which includes his salary and the welfare of his extensive family, by 10 per cent to $61 million, a significant chunk of the kingdom’s overall budget.

- Unsurprisingly, President Biya comes out on top again, earning 229 times what an average Cameroonian earns, followed by Liberia where President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf earns 113 times what her average citizen does.

(Africa Review correspondents, Mail & Guardian South Africa, World Bank Group.)

What African presidents are paid, why it matters

.

.