The #EndSARS Movement Must Challenge Inequality to Survive

by Annie Olaloku-Teriba

@annie_etc_

25 October 2020

20 October 2020 will go down as the darkest day in Nigeria’s history. As a crowd of young Nigerians sat at the Lekki toll gate in Lagos, waving the flag and singing the national anthem, military vehicles blocked both exits and opened fire.

Camped out as part of the #EndSARS movement, which calls for an end to the brutality of Nigeria’s notorious police unit, the Special Anti-Robbery Squad, or SARS, the protestors were seeking to build a country which fulfils the promise “to build a nation where peace and justice shall reign”. Instead, dozens were murdered in cold blood. In a country that spent the majority of its formal independence under military rule, this violence was certainly not exceptional, but under the microscope of a globally trending movement, the brazenness of such a move signalled the utter contempt in which the Nigerian state holds its people.

The events leading up to this atrocity, and the others which have ensued, have only served to deepen the irrevocable blows to the fabric of Nigerian society that have occured over the last three weeks.

Black Tuesday.

At 11.49 am on 20 October, governor Sanwo-Olu of Lagos took to social media to announce that a 24-hour curfew would commence at 4 pm. Three minutes after the curfew began, protesters at the toll gate posted in confusion as men claiming to be from the government moved to remove CCTV cameras in the area. At 5 pm the only light offered by the billboard above the toll gate was cut, blinding protestors staging a peaceful sit-in. An hour later, protesters went live on Instagram as the military opened fire. If not for the power of social media, these events would not be known – over 130,000 people watched user @DJSwitch_’s livestream of the events. Images of dead bodies, overrun hospital wards, ambulances being turned away flooded social media feeds – all time-stamped and verified by a movement that has had to be on guard against the rapid spread of misinformation.

Such misinformation abounded the following day, when Lagos governor Sanwo-Olu addressed the state, claiming that nobody had died at the Lekki toll gate. In his speech, he brazenly suggested that the actions of those security officials who opened fire had been in response to violence from a movement ‘hijacked’ by criminal elements. Why, if this was simply an overzealous response to protester violence, did agents of the state open fire on protesters at a site which had no previous reports of disruption? Later Sanwo-Olu claimed the events were a result of forces beyond his control. By the time president Buhari finally addressed the nation, he didn’t even bother to mention the massacre.

Still, people continued to demand answers. The mounting pressure led governor Sanwo-Olu to backtrack, claiming the massacre was as a result of “forces beyond our direct control [who] moved to make dark notes in our history”. As politician after politician came out to pass the buck, the Nigerian people were asked to believe either that the military is beyond the control of the state, or that there are civilian forces within Nigeria who can commit such an atrocity with impunity. The chilling fact is that both scenarios are not only possible but probable.

One thing is clear though: the massacre at Lekki toll gate was a direct attack on the right to protest, and the fallout should provide key lessons for the nascent movement and its supporters. By the time Sanwo-Olu announced his curfew, prominent fissures in the movement had already started to develop. Segalink, a Twitter personality and campaigner, publicly broke with what many saw as his brainchild, claiming that #EndSARS had morphed from legitimate grievances into an attempted insurrection.

If #EndSars was a coalition of the middle class, working class and lumpen youth, we were already seeing the first cracks.

A nation divided.

The message that #EndSARS is a fight for survival has been at the heart of the movement since it first began. What that survival means, however, is dependent on class and status. If the famous Nigerian faces who gave their two cents to the international press are to be believed, SARS specifically terrorises the wealthy – or “fresh”. Indeed, while many acknowledged the underlying conditions that led to the unrest – a lack of basic provision from the government, no safety net, no water, no electricity – the battle was ultimately presented as one waged by Nigeria’s wealthy, who claimed they faced police brutality as a result of class resentment.

But as the protests spread outside wealthier areas such as Lekki and Abuja, a completely different narrative emerged; one which showed that the brutality of the state was felt most acutely by the country’s poorest: those who don’t have the connections to scare off an officer; who don’t have the resources or platforms to pursue accountability; who can be disappeared and their families bullied into silence.

The consequences of the Nigeria rampant inequality were revealed in the remaining days of Sanwo-Olu’s initial 96-hour lockdown. Given a chance to upend, if only for a short time, the strict socioeconomic hierarchy, the underclasses who remained on the streets focused on desecrating symbols of power and injustice, which had previously been untouchable to them. The protesters raided the palace of the Oba [King] of Lagos, making away with his ceremonial staff, his shoes and dollars they found in a coffin. They burned the homes of wealthy Lagosians. They broke into and emptied a warehouse where Covid-19 palliatives, which the government claimed they had distributed months ago, were hidden.

Of course, the truth of the matter is that the Lagos they burned and ransacked was one in which they had no stake. Branded touts and thugs by the state and prominent #EndSARS protestors, few seemed interested in understanding the depths of destitution which would drive people, en masse, to set fire to their own city; their violence had seemingly made their motivations irrelevant. For months, millions had fallen further into poverty under a Covid-19 lockdown with little to no support from the government and obscene food price inflation brought on by its decision to sharply increase fuel prices in the middle of an economic crisis. But as Lagos burned, they discovered the abundance needlessly hidden in plain sight.

I have one regret in my attempts to shed light on the struggles of the #EndSARS movement: I implicitly accepted the distinction that was made between peaceful and violent protests – between the pacifism of the affluent Lekki and the self-defence of the poorer Mushin – as one of moral legitimacy.

But such judgments are futile, I now realise, given that it was these poor communities who bore the brunt of the state’s initial attempts at crackdown – the water cannon, the firing into crowds, the mass arrests and disappearances. It was they who lived the consequences of the dogmatic idea that only the state can use violence, even as that violence is used so egregiously against its own citizenry.

In the words of Seun Kuti, these communities can’t “leave oppression, comot [remove] SARS” because the impunity of the police is inextricably tied to the impunity of the wealthy. For that reason, no project to curtail the brutality of the police can sidestep the redistribution of wealth and power. It is obvious, however, that some would like to stop short of tackling the latter.

A fairer Nigeria.

Time and time again, the Nigerian state has proven it cannot be entrusted with the welfare of its people. Politicians have gleefully embraced opportunities to put profit before people, hoarding not only the vast wealth of the oil-producing state, but even the scraps donated to the very poorest in the country.

It is now clear that, if the movement is to survive the government’s violent threats and attacks, #EndSARS must take seriously the task of transforming Nigerian society as a whole. Such a task will likely cost the movement some supporters – it goes without saying that for some endorsement ends when it threatens their comfortable place within Nigeria’s unjust system.

Regardless, if the bloodshed is to have meaning, and the martyrs the government have made are to be honoured, those committed to a better and fairer Nigeria must forge ahead.

Annie Olaloku-Teriba is an independent researcher based in London, working on legacies of empire and the complex histories of race.

The #EndSARS Movement Must Challenge Inequality to Survive

by Annie Olaloku-Teriba

@annie_etc_

25 October 2020

20 October 2020 will go down as the darkest day in Nigeria’s history. As a crowd of young Nigerians sat at the Lekki toll gate in Lagos, waving the flag and singing the national anthem, military vehicles blocked both exits and opened fire.

Camped out as part of the #EndSARS movement, which calls for an end to the brutality of Nigeria’s notorious police unit, the Special Anti-Robbery Squad, or SARS, the protestors were seeking to build a country which fulfils the promise “to build a nation where peace and justice shall reign”. Instead, dozens were murdered in cold blood. In a country that spent the majority of its formal independence under military rule, this violence was certainly not exceptional, but under the microscope of a globally trending movement, the brazenness of such a move signalled the utter contempt in which the Nigerian state holds its people.

The events leading up to this atrocity, and the others which have ensued, have only served to deepen the irrevocable blows to the fabric of Nigerian society that have occured over the last three weeks.

Black Tuesday.

At 11.49 am on 20 October, governor Sanwo-Olu of Lagos took to social media to announce that a 24-hour curfew would commence at 4 pm. Three minutes after the curfew began, protesters at the toll gate posted in confusion as men claiming to be from the government moved to remove CCTV cameras in the area. At 5 pm the only light offered by the billboard above the toll gate was cut, blinding protestors staging a peaceful sit-in. An hour later, protesters went live on Instagram as the military opened fire. If not for the power of social media, these events would not be known – over 130,000 people watched user @DJSwitch_’s livestream of the events. Images of dead bodies, overrun hospital wards, ambulances being turned away flooded social media feeds – all time-stamped and verified by a movement that has had to be on guard against the rapid spread of misinformation.

Such misinformation abounded the following day, when Lagos governor Sanwo-Olu addressed the state, claiming that nobody had died at the Lekki toll gate. In his speech, he brazenly suggested that the actions of those security officials who opened fire had been in response to violence from a movement ‘hijacked’ by criminal elements. Why, if this was simply an overzealous response to protester violence, did agents of the state open fire on protesters at a site which had no previous reports of disruption? Later Sanwo-Olu claimed the events were a result of forces beyond his control. By the time president Buhari finally addressed the nation, he didn’t even bother to mention the massacre.

Still, people continued to demand answers. The mounting pressure led governor Sanwo-Olu to backtrack, claiming the massacre was as a result of “forces beyond our direct control [who] moved to make dark notes in our history”. As politician after politician came out to pass the buck, the Nigerian people were asked to believe either that the military is beyond the control of the state, or that there are civilian forces within Nigeria who can commit such an atrocity with impunity. The chilling fact is that both scenarios are not only possible but probable.

One thing is clear though: the massacre at Lekki toll gate was a direct attack on the right to protest, and the fallout should provide key lessons for the nascent movement and its supporters. By the time Sanwo-Olu announced his curfew, prominent fissures in the movement had already started to develop. Segalink, a Twitter personality and campaigner, publicly broke with what many saw as his brainchild, claiming that #EndSARS had morphed from legitimate grievances into an attempted insurrection.

If #EndSars was a coalition of the middle class, working class and lumpen youth, we were already seeing the first cracks.

A nation divided.

The message that #EndSARS is a fight for survival has been at the heart of the movement since it first began. What that survival means, however, is dependent on class and status. If the famous Nigerian faces who gave their two cents to the international press are to be believed, SARS specifically terrorises the wealthy – or “fresh”. Indeed, while many acknowledged the underlying conditions that led to the unrest – a lack of basic provision from the government, no safety net, no water, no electricity – the battle was ultimately presented as one waged by Nigeria’s wealthy, who claimed they faced police brutality as a result of class resentment.

But as the protests spread outside wealthier areas such as Lekki and Abuja, a completely different narrative emerged; one which showed that the brutality of the state was felt most acutely by the country’s poorest: those who don’t have the connections to scare off an officer; who don’t have the resources or platforms to pursue accountability; who can be disappeared and their families bullied into silence.

The consequences of the Nigeria rampant inequality were revealed in the remaining days of Sanwo-Olu’s initial 96-hour lockdown. Given a chance to upend, if only for a short time, the strict socioeconomic hierarchy, the underclasses who remained on the streets focused on desecrating symbols of power and injustice, which had previously been untouchable to them. The protesters raided the palace of the Oba [King] of Lagos, making away with his ceremonial staff, his shoes and dollars they found in a coffin. They burned the homes of wealthy Lagosians. They broke into and emptied a warehouse where Covid-19 palliatives, which the government claimed they had distributed months ago, were hidden.

Of course, the truth of the matter is that the Lagos they burned and ransacked was one in which they had no stake. Branded touts and thugs by the state and prominent #EndSARS protestors, few seemed interested in understanding the depths of destitution which would drive people, en masse, to set fire to their own city; their violence had seemingly made their motivations irrelevant. For months, millions had fallen further into poverty under a Covid-19 lockdown with little to no support from the government and obscene food price inflation brought on by its decision to sharply increase fuel prices in the middle of an economic crisis. But as Lagos burned, they discovered the abundance needlessly hidden in plain sight.

I have one regret in my attempts to shed light on the struggles of the #EndSARS movement: I implicitly accepted the distinction that was made between peaceful and violent protests – between the pacifism of the affluent Lekki and the self-defence of the poorer Mushin – as one of moral legitimacy.

But such judgments are futile, I now realise, given that it was these poor communities who bore the brunt of the state’s initial attempts at crackdown – the water cannon, the firing into crowds, the mass arrests and disappearances. It was they who lived the consequences of the dogmatic idea that only the state can use violence, even as that violence is used so egregiously against its own citizenry.

In the words of Seun Kuti, these communities can’t “leave oppression, comot [remove] SARS” because the impunity of the police is inextricably tied to the impunity of the wealthy. For that reason, no project to curtail the brutality of the police can sidestep the redistribution of wealth and power. It is obvious, however, that some would like to stop short of tackling the latter.

A fairer Nigeria.

Time and time again, the Nigerian state has proven it cannot be entrusted with the welfare of its people. Politicians have gleefully embraced opportunities to put profit before people, hoarding not only the vast wealth of the oil-producing state, but even the scraps donated to the very poorest in the country.

It is now clear that, if the movement is to survive the government’s violent threats and attacks, #EndSARS must take seriously the task of transforming Nigerian society as a whole. Such a task will likely cost the movement some supporters – it goes without saying that for some endorsement ends when it threatens their comfortable place within Nigeria’s unjust system.

Regardless, if the bloodshed is to have meaning, and the martyrs the government have made are to be honoured, those committed to a better and fairer Nigeria must forge ahead.

Annie Olaloku-Teriba is an independent researcher based in London, working on legacies of empire and the complex histories of race.

The #EndSARS Movement Must Challenge Inequality to Survive

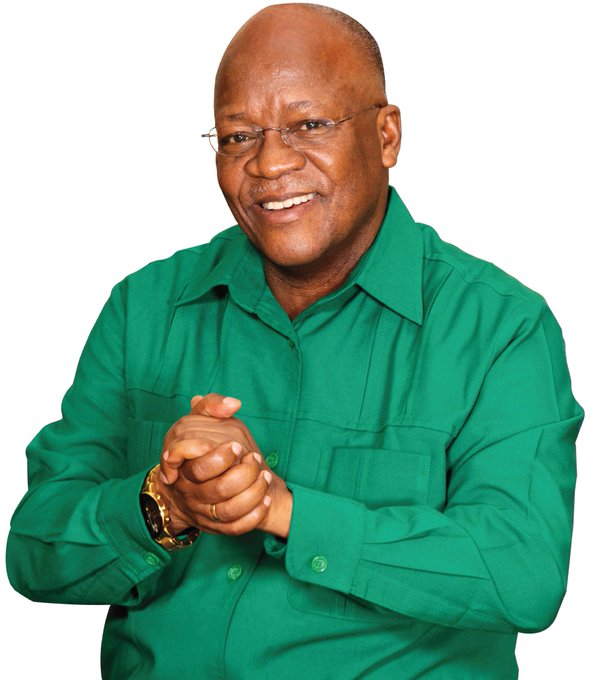

I would love to hear your thoughts on if (or how) Magufuli can overcome his upcoming challenges. If the powers that be(

I would love to hear your thoughts on if (or how) Magufuli can overcome his upcoming challenges. If the powers that be( ) follow their usual strategies, there will be an impending forex shortage as the IMF, WorldBank, Etc stop there currency drip into Tanzania. Furthermore, if Magufuli attempts import substitution; there will be a shortage of forex from the importation of industrial equipment (to facilitate local production). These issues may then be compounded by the need to pay skilled professionals(usually foreign) to train natives in heavy industry, agrarian production, and tech sectors. Do you guys see a way out for Tanzania? Or perhaps an alternative path?

) follow their usual strategies, there will be an impending forex shortage as the IMF, WorldBank, Etc stop there currency drip into Tanzania. Furthermore, if Magufuli attempts import substitution; there will be a shortage of forex from the importation of industrial equipment (to facilitate local production). These issues may then be compounded by the need to pay skilled professionals(usually foreign) to train natives in heavy industry, agrarian production, and tech sectors. Do you guys see a way out for Tanzania? Or perhaps an alternative path?