The new wave of industrial oil palm plantations that has taken place in Africa over the past 15 years is built, quite literally, on the back of this brutal history. The majority of recent industrial oil palm projects that are being implemented involve old concessions, abandoned plantations and long simmering land conflicts.

For communities across African countries, today's industrial oil palm plantation projects are experienced as another round of colonial occupation.

13 Their lands are being taken from them, often by force, without consultation or consent. The industrial plantations destroy their forests and local biodiversity and pollute their water sources. They lose access to lands to grow food as well as their traditional palm groves, and they are forbidden from producing their own palm oil. The companies are only able to produce palm oil for cheap because the labour conditions on their plantations are so bad, often even worse than they were in colonial times, with wages, when they are paid, not covering basic living expenses and the vast majority of jobs being for daily labourers, with no job security. There are barely any social investments, such as schools, clinics and infrastructures, that might provide some compensation-- and villagers rarely see any of the rental payments that companies claim to make.

Much like under the colonial period, villagers living in and around the concession areas are constantly harassed and beaten by company security guards who accuse them of stealing palm fruits from the company plantations. Opponents of the company are also routinely beaten, arrested and intimidated, and sometimes even killed. But it is women who suffer the most, and almost always in silence. The level of sexual violence faced by women living around the plantations or working at the plantations is generally horrific.

14

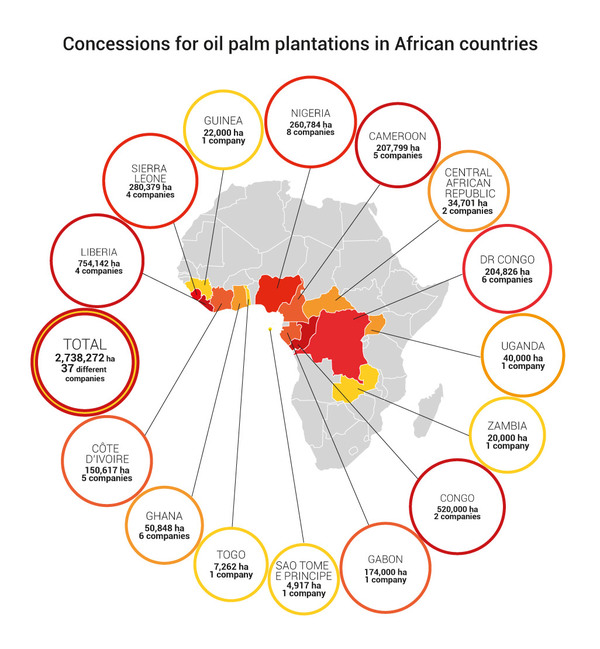

Yet today's agrocolonialism is nevertheless cloaked in the story of a mission to help Africa, just as it was during the colonial period. All of the companies claim to be "responsible investors", with several adhering to the principles of the Roundtable for Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) and making 'zero deforestation' pledges. Although the RSPO certification criteria cannot be considered sustainable, since it promotes industrial plantations, it is interesting to see how few of these companies have achieved RSPO certification for their industrial plantations in African countries. Only 9 of the 52 large scale oil palm plantations in operation in Africa have RSPO certification.

Most of the corporate plantation projects include outgrower schemes, where the companies organise local smallholders to supply them with oil palm fruits. Sometimes, companies lure farmers into these programmes by providing seedlings and promising that such schemes are a way for villagers to 'get rich quickly'. These programmes are sometimes written into the concession agreements with the government and companies often receive funding from African governments, UN institutions, donors or development banks for these outgrower or smallholder programmes. In several cases, the schemes are carried out with the collaboration of NGOs. Some outgrower schemes have existed for decades, and were established through the World Bank funded industrial oil palm programmes of the 1970s and 1980s. This is the case in Ghana, where the area under outgrower schemes is larger than the area under industrial plantations.

15 In most recent cases, however, these outgrower schemes are not the priority for the companies, and the companies channel far more of their resources into their own company plantations, for which they can maintain stricter control over production.

Olam, for example, established a joint venture company with the Gabon government to develop ‘outgrower’ programmes in nine provinces to allegedly support the country's food security. The programme, called GRAINE, is supposed to develop smallholder plantations of oil palms and other crops covering 200,000 ha and involving 1,600 villages by 2020. Yet, by the end of 2017, the joint venture had invested $40 million in the GRAINE programme, in contrast with the $643 million that Olam's plantation company spent on its own industrial plantations. Moreover, rather than increase food production, the GRAINE programme had instead devoted the funding it received from the African Development Bank to the development of a large oil palm plantation on a 30,000 ha concession in the savannah zone at Ndendé in Ngounié province.

16 A recent report indicated that this GRAINE oil palm plantation may now be handed over to Olam's plantation company!

17

Where companies are actually implementing outgrower programmes or maintaining the smallholder schemes initiated by the previous plantation owners, the results are not much better. The villagers participating in these programmes have to cultivate industrial oil palms exclusively on part or on all of their lands and must produce exclusively for the company. The company sets the terms of the contract and determines the prices that are paid. Experience shows that the companies typically fix the contracts to guarantee their profits, while the villagers end up in debt at the end of each year. The villagers also sacrifice lands that they could have used to produce food for their families and communities.

Corporate oil palm projects are clearly a disaster for the local communities where they are based. The number of failed projects and the losses incurred by many active plantation companies at their operations in Africa seem to indicate that the companies are not profiting much either. But this does not mean that the main people behind these companies do not profit. The executives and directors of loss making oil palm plantation companies always ensure that they are paid handsomely, through salaries, bonuses, share options and all kinds of "service fees" or exaggerated expenses that they charge to the companies. While a company like Feronia Inc, which is heavily financed by development banks, complains of not being able to pay its workers even the legal minimum wage or to build decent health clinics within its concession in the DR Congo, its top executives received over $2 million in salaries and share options in 2017.

18 Moreover, when there are (declared) profits, such as with some of the SOCFIN owned plantation companies in Africa, most of the profits are distributed to the shareholders, and are not used to improve the wages of its workers or to construct the social projects that were promised to communities.

19