You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Essential The Africa the Media Doesn't Tell You About

- Thread starter TommyHilltrigga

- Start date

More options

Who Replied?My girl is from Entebbe but Kamapla seems lit. I plan on going to Uganda in April 2020.

The Odum of Ala Igbo

Hail Biafra!

Frangala

All Star

Politics

Trump-Linked Lobbyists Help Nigerian Politician Gain U.S. Access

By

Christian Berthelsen

February 4, 2019, 2:10 PM EST Updated on February 4, 2019, 5:13 PM EST

Brian Ballard Photographer: Andrew Harrer/Bloomberg

Until last month, Nigerian presidential candidate Atiku Abubakar had a problem. He was persona non grata in the U.S. after cropping up in connection with several corruption investigations.

Then the cloud lifted. Years after he’d last been seen in the U.S., Abubakar surfaced in Washington in January. He held court at the Trump International Hotel. He met with members of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and Congress. Those meetings were trumpeted to his followers back home on Facebook and Twitter. The public tour has helped silence opponents who said Abubakar couldn’t effectively lead one of Africa’s biggest economies if he wasn’t even welcome in the U.S.

Atiku Abubakar

Photographer: George Osodi/Bloomberg

Abubakar had been blocked from entering the U.S. under a State Department edict applying to officials linked to foreign corruption, two former U.S. officials said. One of them said the Nigerian had been seeking a waiver to enter the country for years and expressed surprise when told that the effort was ultimately successful.

Abubakar’s rehabilitation was driven in part by Washington lobbyists and lawyers with links to President Donald Trump’s 2016 presidential race. Ballard Partners -- run by Brian Ballard, a fundraiser for Trump’s campaign who now has a deep roster of clients eager for an inside track to the administration -- helped set up meetings for the candidate in the U.S., according to people familiar with the firm’s work for him.

Read More: Trump’s Florida Fundraiser Flourishes as New Washington Lobbyist

Video: Atiku Abubakar on Nigeria’s Central Bank and NNPC State Oil Company

Law firm Holland & Knight lobbied the State Department, House of Representatives and National Security Council on Abubakar’s behalf on visa issues, according to a disclosure filed with Congress. The firm’s lead lobbyist on the effort was Scott Mason, who previously directed congressional relations for Trump’s campaign and transition team.

In defusing opponents’ chief criticism, the U.S. visit and meetings positioned Abubakar as a stronger challenger, not to mention a potential international partner to the U.S. should he prevail in Nigeria’s Feb. 16 presidential race. He’s the leading opposition candidate to run Africa’s most populous nation and top petroleum producer, where wealth and corruption mix with extreme poverty to create deep concerns about security and safety.

A member of Abubakar’s communications team, Boladale Adekoya, denied Abubakar had been banned from the U.S. A State Department representative declined to comment.

Mason didn’t immediately respond to a request for comment. Ballard referred questions to its lead lobbyist for Abubakar’s political party, James P. Rubin, who said he wasn’t involved in getting the travel visa and was focused on pushing for fair elections in Nigeria.

Cash in Freezer

Abubakar’s troubles with the U.S. date back more than a decade. In 2004, George W. Bush signed a presidential proclamation meant to deny corrupt foreign officials a coveted luxury -- fluid access to the good life in America and a safe place to stash ill-gotten proceeds.

Abubakar’s name surfaced in two criminal cases in the U.S. -- the prosecution of German engineering giant Siemens AG for paying bribes to officials in Africa, and the prosecution of former U.S. Representative William Jefferson.

In the latter case, Abubakar, then Nigeria’s vice president, gained notoriety for his connection to $90,000 in cash found in Jefferson’s freezer in 2005. In a secretly videotaped conversation, Jefferson told an undercover informant that the money was for Abubakar, intended to smooth the way for a U.S. company’s African expansion. Prosecutors never introduced evidence showing Abubakar solicited or accepted a bribe, and he was never prosecuted. Jefferson was convicted, though his case was partially overturned on appeal.

Abubakar was also the subject of a 2010 congressional investigation, which found that he and his wife transferred more than $40 million in suspect funds into the U.S. from offshore corporations. Lawmakers said Abubakar held a stake in an oil-services company that received hundreds of millions of dollars in payments from Western companies seeking to do business in Africa, including when he was vice president.

Abubakar has attributed his wealth to prudent investments and luck. In an interview, Edward Weidenfeld, a Washington lawyer who represented Abubakar at the time of the Jefferson and Siemens cases, said he maintained his innocence in those proceedings.

Adekoya, the Abubakar spokesman, said Jefferson had falsely accused Abubakar of being the intended recipient of the cash. Regarding the $40 million Abubakar brought into the U.S., Adekoya said it was intended as payment to American University to launch a school in Nigeria. He added that Abubakar is a “reputable entrepreneur" and a successful businessman, that his funds were from legitimate business ventures and that his oil-services stake was held in trust while he was in office.

Visa Waiver

Once the State Department bars a foreign official it becomes difficult to get the ban rescinded, according to the two officials. By U.S. law, the status of visa applications is confidential. So are the identities of barred foreign officials. The process by which people get on or off the list is also opaque.

In certain cases, the department will grant temporary waivers allowing dignitaries to visit, often with limits on duration and itinerary. If indeed a ban were in place, Abubakar may have been granted a waiver to encourage good relations should he win, one of the officials said.

Holland & Knight, which was hired at the end of October, disclosed payments of $80,000 in relation to its visa work for Abubakar.

Through his spokesman, Abubakar said he applied for and received a visa through the U.S. mission in Nigeria.

Abubakar’s People’s Democratic Party of Nigeria inked a $1.1 million annual contract with Ballard Partners last fall, according to foreign lobbying records filed with the Justice Department. People familiar with Ballard’s work on Abubakar’s behalf said it included getting him a meeting at the State Department during his visit and shepherding him to various events.

Rubin, Ballard’s primary lobbyist on behalf of Abubakar’s party, was an assistant secretary of state during the Clinton administration. He joined Ballard’s firm as a lobbyist last year, according to a disclosure filing. (He was also previously an executive who helped lead Bloomberg’s editorial page, then called Bloomberg View.)

“My work on behalf of the People’s Democratic Party exclusively focused on pushing for free and fair elections and did not involve any consular matter or visa matter,” Rubin said.

Ballard’s Roster

declined to pursue fraud charges against Trump University after Trump’s charitable foundation gave $25,000 in 2013 to a re-election fund for Bondi.

During his visit, Abubakar held a “town hall” at the Trump International Hotel in Washington to meet with Nigerians in the U.S. He also appeared on a panel at the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, stopped at the office of the Voice of America and met with Representative Chris Smith, a New Jersey Republican. Abubakar’s campaign broadcast the town hall meeting on Facebook, and he posted a string of photos of his U.S. visit and meetings to his Twitter account, including one from his arrival at the airport putting him back on U.S. soil.

A spokesman for Smith didn’t respond to questions about the meeting. A Chamber of Commerce spokeswoman said the roundtable discussion was private.

— With assistance by Greg Farrell, Tope Alake, and Bill Allison

Trump-Linked Lobbyists Help Nigerian Politician Gain U.S. Access

By

Christian Berthelsen

February 4, 2019, 2:10 PM EST Updated on February 4, 2019, 5:13 PM EST

-

U.S. visa long eluded candidate who cropped up in graft probes -

Ballard Partners, run by ex-Trump aide, planned D.C. meetings

Brian Ballard Photographer: Andrew Harrer/Bloomberg

Until last month, Nigerian presidential candidate Atiku Abubakar had a problem. He was persona non grata in the U.S. after cropping up in connection with several corruption investigations.

Then the cloud lifted. Years after he’d last been seen in the U.S., Abubakar surfaced in Washington in January. He held court at the Trump International Hotel. He met with members of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and Congress. Those meetings were trumpeted to his followers back home on Facebook and Twitter. The public tour has helped silence opponents who said Abubakar couldn’t effectively lead one of Africa’s biggest economies if he wasn’t even welcome in the U.S.

Atiku Abubakar

Photographer: George Osodi/Bloomberg

Abubakar had been blocked from entering the U.S. under a State Department edict applying to officials linked to foreign corruption, two former U.S. officials said. One of them said the Nigerian had been seeking a waiver to enter the country for years and expressed surprise when told that the effort was ultimately successful.

Abubakar’s rehabilitation was driven in part by Washington lobbyists and lawyers with links to President Donald Trump’s 2016 presidential race. Ballard Partners -- run by Brian Ballard, a fundraiser for Trump’s campaign who now has a deep roster of clients eager for an inside track to the administration -- helped set up meetings for the candidate in the U.S., according to people familiar with the firm’s work for him.

Read More: Trump’s Florida Fundraiser Flourishes as New Washington Lobbyist

Video: Atiku Abubakar on Nigeria’s Central Bank and NNPC State Oil Company

Law firm Holland & Knight lobbied the State Department, House of Representatives and National Security Council on Abubakar’s behalf on visa issues, according to a disclosure filed with Congress. The firm’s lead lobbyist on the effort was Scott Mason, who previously directed congressional relations for Trump’s campaign and transition team.

In defusing opponents’ chief criticism, the U.S. visit and meetings positioned Abubakar as a stronger challenger, not to mention a potential international partner to the U.S. should he prevail in Nigeria’s Feb. 16 presidential race. He’s the leading opposition candidate to run Africa’s most populous nation and top petroleum producer, where wealth and corruption mix with extreme poverty to create deep concerns about security and safety.

A member of Abubakar’s communications team, Boladale Adekoya, denied Abubakar had been banned from the U.S. A State Department representative declined to comment.

Mason didn’t immediately respond to a request for comment. Ballard referred questions to its lead lobbyist for Abubakar’s political party, James P. Rubin, who said he wasn’t involved in getting the travel visa and was focused on pushing for fair elections in Nigeria.

Cash in Freezer

Abubakar’s troubles with the U.S. date back more than a decade. In 2004, George W. Bush signed a presidential proclamation meant to deny corrupt foreign officials a coveted luxury -- fluid access to the good life in America and a safe place to stash ill-gotten proceeds.

Abubakar’s name surfaced in two criminal cases in the U.S. -- the prosecution of German engineering giant Siemens AG for paying bribes to officials in Africa, and the prosecution of former U.S. Representative William Jefferson.

In the latter case, Abubakar, then Nigeria’s vice president, gained notoriety for his connection to $90,000 in cash found in Jefferson’s freezer in 2005. In a secretly videotaped conversation, Jefferson told an undercover informant that the money was for Abubakar, intended to smooth the way for a U.S. company’s African expansion. Prosecutors never introduced evidence showing Abubakar solicited or accepted a bribe, and he was never prosecuted. Jefferson was convicted, though his case was partially overturned on appeal.

Abubakar was also the subject of a 2010 congressional investigation, which found that he and his wife transferred more than $40 million in suspect funds into the U.S. from offshore corporations. Lawmakers said Abubakar held a stake in an oil-services company that received hundreds of millions of dollars in payments from Western companies seeking to do business in Africa, including when he was vice president.

Abubakar has attributed his wealth to prudent investments and luck. In an interview, Edward Weidenfeld, a Washington lawyer who represented Abubakar at the time of the Jefferson and Siemens cases, said he maintained his innocence in those proceedings.

Adekoya, the Abubakar spokesman, said Jefferson had falsely accused Abubakar of being the intended recipient of the cash. Regarding the $40 million Abubakar brought into the U.S., Adekoya said it was intended as payment to American University to launch a school in Nigeria. He added that Abubakar is a “reputable entrepreneur" and a successful businessman, that his funds were from legitimate business ventures and that his oil-services stake was held in trust while he was in office.

Visa Waiver

Once the State Department bars a foreign official it becomes difficult to get the ban rescinded, according to the two officials. By U.S. law, the status of visa applications is confidential. So are the identities of barred foreign officials. The process by which people get on or off the list is also opaque.

In certain cases, the department will grant temporary waivers allowing dignitaries to visit, often with limits on duration and itinerary. If indeed a ban were in place, Abubakar may have been granted a waiver to encourage good relations should he win, one of the officials said.

Holland & Knight, which was hired at the end of October, disclosed payments of $80,000 in relation to its visa work for Abubakar.

Through his spokesman, Abubakar said he applied for and received a visa through the U.S. mission in Nigeria.

Abubakar’s People’s Democratic Party of Nigeria inked a $1.1 million annual contract with Ballard Partners last fall, according to foreign lobbying records filed with the Justice Department. People familiar with Ballard’s work on Abubakar’s behalf said it included getting him a meeting at the State Department during his visit and shepherding him to various events.

Rubin, Ballard’s primary lobbyist on behalf of Abubakar’s party, was an assistant secretary of state during the Clinton administration. He joined Ballard’s firm as a lobbyist last year, according to a disclosure filing. (He was also previously an executive who helped lead Bloomberg’s editorial page, then called Bloomberg View.)

“My work on behalf of the People’s Democratic Party exclusively focused on pushing for free and fair elections and did not involve any consular matter or visa matter,” Rubin said.

Ballard’s Roster

declined to pursue fraud charges against Trump University after Trump’s charitable foundation gave $25,000 in 2013 to a re-election fund for Bondi.

During his visit, Abubakar held a “town hall” at the Trump International Hotel in Washington to meet with Nigerians in the U.S. He also appeared on a panel at the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, stopped at the office of the Voice of America and met with Representative Chris Smith, a New Jersey Republican. Abubakar’s campaign broadcast the town hall meeting on Facebook, and he posted a string of photos of his U.S. visit and meetings to his Twitter account, including one from his arrival at the airport putting him back on U.S. soil.

A spokesman for Smith didn’t respond to questions about the meeting. A Chamber of Commerce spokeswoman said the roundtable discussion was private.

— With assistance by Greg Farrell, Tope Alake, and Bill Allison

loyola llothta

☭☭☭

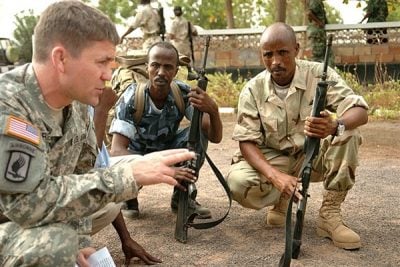

U.S. Military Says It Has a “Light Footprint” in Africa. These Documents Show a Vast Network of Bases.

By Nick Turse

1 December 2018

The U.S. military has long insisted that it maintains a “light footprint” in Africa, and there have been reports of proposed drawdowns in special operations forces and closures of outposts on the continent, due to a 2017 ambush in Niger and an increasing focus on rivals like China and Russia. But through it all, U.S. Africa Command has fallen short of providing concrete information about its bases on the continent, leaving in question the true scope of the American presence there.

The original source of this article is The Intercept

Copyright © Nick Turse, The Intercept, 2019

By Nick Turse

1 December 2018

The U.S. military has long insisted that it maintains a “light footprint” in Africa, and there have been reports of proposed drawdowns in special operations forces and closures of outposts on the continent, due to a 2017 ambush in Niger and an increasing focus on rivals like China and Russia. But through it all, U.S. Africa Command has fallen short of providing concrete information about its bases on the continent, leaving in question the true scope of the American presence there.

Documents obtained from AFRICOM by The Intercept, via the Freedom of Information Act, however, offer a unique window onto the sprawling network of U.S. military outposts in Africa, including previously undisclosed or unconfirmed sites in hotspots like Libya, Niger, and Somalia. The Pentagon has also told The Intercept that troop reductions in Africa will be modest and phased-in over several years and that no outposts are expected to close as a result of the personnel cuts.

According to a 2018 briefing by AFRICOM science adviser Peter E. Teil, the military’s constellation of bases includes 34 sites scattered across the continent, with high concentrations in the north and west as well as the Horn of Africa. These regions, not surprisingly, have also seen numerous U.S. drone attacks and low-profile commando raids in recent years. For example, Libya — the site of drone and commando missions, but for which President Donald Trump said he saw no U.S. military role just last year — is nonetheless home to three previously undisclosed outposts.

“U.S. Africa Command’s posture plan is designed to secure strategic access to key locations on a continent characterized by vast distances and limited infrastructure,” Gen. Thomas Waldhauser, the AFRICOM commander, told the House Armed Services Committee earlier this year, though he didn’t provide specifics on the number of bases. “Our posture network allows forward staging of forces to provide operational flexibility and timely response to crises involving U. S. personnel or interests without creating the optic that U. S. Africa Command is militarizing Africa.”

According to Adam Moore, an assistant professor of geography at the University of California, Los Angeles and an expert on the U.S. military’s presence in Africa,

“It is getting harder for the U.S. military to plausibly claim that it has a ‘light footprint’ in Africa. In just the past five years, it has established what is perhaps the largest drone complex in the world in Djibouti — Chabelley — which is involved in wars on two continents, Yemen, and Somalia.”

Moore also noted that the U.S. is building an even larger drone base in Agadez, Niger.

“Certainly, for people living in Somalia, Niger, and Djibouti, the notion that the U.S. is not militarizing their countries rings false,” he added.

For the last 10 years, AFRICOM has not only sought to define its presence as limited in scope, but its military outposts as small, temporary, and little more than local bases where Americans are tenants. For instance, this is how Waldhauser described a low-profile drone outpost in Tunisia last year: “And it’s not our base, it’s the Tunisians’ base.” On a visit to a U.S. facility in Senegal this summer, the AFRICOM chief took pains to emphasize that the U.S. had no intension of establishing a permanent base there. Still, there’s no denying the scope of AFRICOM’s network of outposts, nor the growth in infrastructure. Air Forces Africa alone, the command’s air component, has recently completed or is currently working on nearly 30 construction projects across four countries in Africa.

“The U.S. footprint on the African continent has grown markedly over the last decade to promote U.S. security interests on the continent,” Navy Cmdr. Candice Tresch, a Pentagon spokesperson, told The Intercept.

While China, France, Russia, and the United Arab Emirates have increased their own military engagement in Africa in recent years and a number of countries now possess outposts on the continent, none approach the wide-ranging U.S. footprint. China, for example, has just one base in Africa – a facility in Djibouti.

According to the documents obtained by The Intercept through the Freedom of Information Act, AFRICOM’s network of bases includes larger “enduring” outposts, consisting of forward operating sites, or FOSes, and cooperative security locations, or CSLs, as well as more numerous austere sites known as contingency locations, or CLs. All of these are located on the African continent except for an FOS on Britain’s Ascension Island in the south Atlantic. Teil’s map of AFRICOM’s “Strategic Posture” names the specific locations of all 14 FOSes and CSLs and provides country-specific locales for the 20 contingency locations. The Pentagon would not say whether the tally was exhaustive, however, citing concerns about publicly providing the number of forces deployed to specific facilities or individual countries. “For reasons of operational security, complete and specific force lay-downs are not releasable,” said Tresch.

While troops and outposts periodically come and go from the continent, and some locations used by commandos conducting sensitive missions are likely kept under wraps, Teil’s map represents the most current and complete accounting available and indicates the areas of the continent of greatest concern to Africa Command.

“The distribution of bases suggests that the U.S. military is organized around three counter-terrorism theaters in Africa: the Horn of Africa — Somalia, Djibouti, Kenya; Libya; and the Sahel — Cameroon, Chad, Niger, Mali, Burkina Faso,” says Moore, noting that the U.S. has only one base in the south of the continent and has scaled back engagement in Central Africa in recent years.

The original source of this article is The Intercept

Copyright © Nick Turse, The Intercept, 2019

loyola llothta

☭☭☭

U.S. Africa Command’s “Strategic Posture” — listing 34 military outposts — from a 2018 briefing by Science Advisor Peter E. Teil. (Source: U.S. Africa Command)

Niger, Somalia, and Kenya

Teil’s briefing confirms, for the first time, that the U.S. military currently has more sites in Niger — five, including two cooperative security locations — than any other country on the western side of the continent. Niamey, the country’s capital, is the location of Air Base 101, a longtime U.S. drone outpost attached to Diori Hamani International Airport; the site of a Special Operations Advanced Operations Base; and the West Africa node for AFRICOM’s contractor-provided personnel recovery and casualty evacuation services. The other CSL, in the remote smuggling hub of Agadez, is set to become the premier U.S. military outpost in West Africa. That drone base, located at Nigerien Air Base 201, not only boasts a $100 million construction price tag but, with operating expenses, is estimated to cost U.S. taxpayers more than a quarter-billion dollars by 2024 when the 10-year agreement for its use ends.

Officially, a CSL is neither “a U.S. facility or base.” It is, according to the military, “simply a location that, when needed and with the permission of the partner country, can be used by U.S. personnel to support a wide range of contingencies.” The sheer dimensions, cost, and importance of Agadez seems to suggest otherwise.

“Judging by its size and the infrastructure investments to date, Agadez more resembles massive bases that the military created in Iraq and Afghanistan than a small, unobtrusive, ‘lily pad,’” says Moore.

The U.S. military presence in Niger gained widespread exposure last year when an October 4 ambush by ISIS in the Greater Sahara near the Mali border killed four U.S. soldiers, including Green Berets, and wounded two others. A Pentagon investigation into the attack shed additional light on other key U.S. military sites in Niger including Ouallam and Arlit, where Special Operations forces (SOF) deployed in 2017, and Maradi, where SOF were sent in 2016. Arlit also appeared as a proposed contingency location in a formerly secret 2015 AFRICOM posture plan obtained by The Intercept. Ouallam, which was listed in contracting documents brought to light by The Intercept last year, was the site of an SOF effort to train and equip a Nigerian counterterrorism company as well as another effort to conduct operations with other local units. Contracting documents from 2017 also noted the need for 4,400 gallons per month of gasoline, 1,100 gallons per month of diesel fuel, and 6,000 gallons of aviation turbine fuel to be delivered, every 90 days, to a “military installation” in Dirkou.

While the five bases in Niger anchor the west of the continent, the five U.S. outposts in Somalia are tops in the east. Somalia is the East Africa hub for contractor-provided personnel recovery and casualty evacuation services as well as the main node for the military’s own personnel recovery and casualty evacuation operations. These sites, revealed in AFRICOM maps for the first time, do not include a CIA base revealed in 2014 by The Nation.

All U.S. military facilities in Somalia, by virtue of being contingency locations, are unnamed on AFRICOM’s 2018 map. Previously, Kismayo has been identified as a key outpost, while the declassified 2015 AFRICOM posture plan names proposed CLs in Baidoa, Bosaaso, and the capital, Mogadishu, as well as Berbera in the self-declared state of Somaliland. If locations on Teil’s map are accurate, one of the Somali sites is located in this latter region. Reporting by Vice News earlier this year indicated there were actually six new U.S facilities being constructed in Somalia as well as the expansion of Baledogle, a base for which a contract for “emergency runway repairs” was recently issued.

According to top secret documents obtained by The Intercept in 2015, elite troops from a unit known as Task Force 48-4 were involved in drone attacks in Somalia earlier this decade. This air war has continued in the years since. The U.S. has already conducted 36 air strikes in Somalia this year, compared to 34 for all of 2017 and 15 in 2016, according to the Foundation for Defense of Democracies.

Somalia’s neighbor, Kenya, boasts four U.S. bases. These include cooperative security locations at Mombasa as well as Manda Bay, where a 2013 Pentagon study of secret drone operations in Somalia and Yemen noted that two manned fixed-wing aircraft were then based. AFRICOM’s 2015 posture plan also mentions contingency locations at Lakipia, the site of a Kenyan Air Force base, and another Kenyan airfield at Wajir that was upgraded and expanded by the U.S. Navy earlier in this decade.

loyola llothta

☭☭☭

Libya, Tunisia, and Djibouti

Teil’s map shows a cluster of three unnamed and previously unreported contingency locations near the Libyan coastline. Since 2011, the U.S. has carried out approximately 550 drone strikes targeting al Qaeda and Islamic State militants in the restive North African nation. During a four-month span in 2016, for example, there were around 300 such attacks, according to U.S. officials. That’s seven times more than the 42 confirmed U.S. drone strikes carried out in Somalia, Yemen, and Pakistan combined for all of 2016, according to data compiled by the Bureau of Investigative Journalism, a London-based nonprofit news organization. The Libya attacks have continued under the Trump administration, with the latest acknowledged U.S. drone strike occurring near Al Uwaynat on November 29. AFRICOM’s 2015 posture plan listed only an outpost at Al-Wigh, a Saharan airfield near that country’s borders with Niger, Chad, and Algeria, located far to the south of the three current CLs.

Africa Command’s map also shows a contingency location in neighboring Tunisia, possibly Sidi Ahmed Air Base, a key regional U.S. drone outpost that has played an important role in air strikes in Libya in recent years.

“You know, flying intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance drones out of Tunisia has been taking place for quite some time,” said Waldhauser, the AFRICOM commander, last year. “[W]e fly there, it’s not a secret, but we are very respectful to the Tunisians’ desires in terms of, you know, how we support them and the fact that we have [a] low profile…”

Djibouti is home to the crown jewel of U.S. bases on the continent, Camp Lemonnier, a former French Foreign Legion outpost and AFRICOM’s lone forward operating site on the continent. A longtime hub for counterterrorism operations in Yemen and Somalia and the home of Combined Joint Task Force-Horn of Africa (CJTF–HOA), Camp Lemonnier hosts around 4,000 U.S. and allied personnel, and, according to Teil, is the “main platform” for U.S. crisis response forces in Africa. Since 2002, the base has expanded from 88 acres to nearly 600 acres and spun off a satellite outpost — a cooperative security location 10 kilometers to the southwest, where drone operations in the country were relocated in 2013. Chabelley Airfieldhas gone on to serve as an integral base for missions in Somalia and Yemenas well as the drone war against the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria.

“United States military personnel remain deployed to Djibouti, including for purposes of posturing for counterterrorism and counter-piracy operations in the vicinity of the Horn of Africa and the Arabian Peninsula, and to provide contingency support for embassy security augmentation in East Africa,” President Donald Trump noted in June.

loyola llothta

☭☭☭

A map of U.S. military bases — forward operating sites, cooperative security locations, and contingency locations — across the African continent from declassified Fiscal Year 2015 U.S. Africa Command planning documents. (Source: U.S. Africa Command)

Cameroon, Mali, and Chad

AFRICOM’s strategic posture also includes two contingency locations in Cameroon. One is an outpost in the north of the country, known as CL Garoua, which is used to fly drone missions and also as a base for the Army’s Task Force Darby, which supports Cameroonian forces fighting the terrorist group Boko Haram. Cameroon is also home to a longtime outpost in Douala as well as U.S. facilities in Maroua and a nearby base called Salak, which is also used by U.S. personnel and private contractors for training missions and drone surveillance. In 2017, Amnesty International, the London-based research firm Forensic Architecture, and The Intercept exposed illegal imprisonment, torture, and killings by Cameroonian troops at Salak.

In neighboring Mali, there are two contingency locations. AFRICOM’s 2015 posture plan lists proposed CLs in Gao and Mali’s capital, Bamako. The 2018 map also notes the existence of a CSL in Chad’s capital N’Djamena, a site where the U.S. began flying drones earlier this decade; it’s also the headquarters of a Special Operations Command and Control Element, an elite battalion-level command. Another unidentified contingency location in Chad could be a CL in Faya Largeau, which was mentioned in AFRICOM’s 2015 posture plan.

In Gabon, a cooperative security location exists in Libreville. Last year, U.S. troops carried out an exercise there to test their ability to turn the Libreville CSL into a forward command post to facilitate an influx of a large number of forces. A CSL can also be found in Accra, Ghana, and another CSL is located on a small compound at Captain Andalla Cissé Air Base in Dakar, Senegal.

“This location is very important to us because it helps mitigate the time and space on the continent the size of Africa,” said AFRICOM commander Waldhauser while visiting the Senegalese capital earlier this year.

Only one base lies in the far south of the continent, a CSL in Botswana’s capital, Gaborone, that is run by the Army. To its north, CSL Entebbe in Uganda has long been an important air base for American forces in Africa, serving as a hub for surveillance aircraft. It also proved integral to Operation Oaken Steel, the July 2016 rapid deployment of troops to rescue U.S. personnel after fighting broke out near the American Embassy in Juba, South Sudan.

“We Have Increased the Firepower”

In May, responding to questions about measures taken after the October 2017 ambush in Niger, Waldhauser spoke of fortifying the U.S. presence on the continent.

“We have increased, which I won’t go into details here, but we have increased the firepower, we’ve increased the ISR [intelligence surveillance and reconnaissance] capacity, we’ve increased various response times,” he said. “So we have beefed up a lot of things posture-wise with regard to these forces.” This firepower includes drones. “We have been arming out of Niger, and we’ll use that as appropriate,” Waldhauser noted this summer, alluding to the presence of armed remotely piloted aircraft, or RPAs, now based there.

AFRICOM did not respond to multiple requests to interview Waldhauser.

After months of reports that the Defense Department was considering a major drawdown of Special Operations forces in Africa as well as the closure of military outposts in Tunisia, Cameroon, Libya and Kenya, the Pentagon now says that less than 10 percent of 7,200 forces assigned to AFRICOM will be withdrawn over several years and no bases will close as a result. In fact, U.S. base construction in Africa is booming. Air Forces Africa spokesperson Auburn Davis told The Intercept that the Air Force recently completed 21 construction projects in Kenya, Tunisia, Niger and Djibouti and currently has seven others underway in Niger and Djibouti.

“The proliferation of bases in the Sahel, Libya, and Horn of Africa suggests that AFRICOM’s counterterrorism missions in those regions of the continent will continue indefinitely,” Moore told The Intercept.

Hours after Moore made those comments, the Pentagon announced that six firms had been named under a potential five-year, $240 million contract for design and construction services for naval facilities in Africa, beginning with the expansion of the tarmac at Camp Lemonnier in Djibouti.

The Odum of Ala Igbo

Hail Biafra!

Nigeria is surrounded

loyola llothta

☭☭☭

i remember telling nikkas about listening to the west about that bs coup. now the same cacs and c00ns that was cosigning the coup just to get mugage out .... all disappear on the topic. making up lies and shyt

but but but get Mugabe out

The Odum of Ala Igbo

Hail Biafra!

i remember telling nikkas about listening to the west about that bs coup. now the same cacs and c00ns that was cosigning the coup just to get mugage out .... all disappear on the topic. making up lies and shyt

but but but get Mugabe out

Mugabe killed thousands of Ndebele in the 1980s and made survivors dance on the graves of their murdered family members

loyola llothta

☭☭☭

you talking about Gukurahundi ?Mugabe killed thousands of Ndebele in the 1980s and made survivors dance on the graves of their murdered family members

Emmerson Mnangagwa was minister of state security at that time and said to managed the Gukurahundi massacres. He was operating the Central Intelligence Organization in Zim. they used the CIO operatives to track down the opposition names and tagged operatives with special army force to go to villages to villages killing villagers.

Mugabe deny knowing the massacres... which i don't believe(with the British and america helping censoring the violence) but if you have problems with Mugabe involvement with Gukurahundi how tf you dont have problems or just cool with the new coup president Emmerson Mnangagwa who said to ignite and carry out the violence

loyola llothta

☭☭☭

Mthuli Ncube’s Former Boss Arrested In Angola Together With Former President’s Son

MaveriqSeptember 26, 2018

More: Bloomberg

MaveriqSeptember 26, 2018

Finance Minister Mthuli Ncube’s former boss and founder of Quantum Global Jean Claude Bastos de Morais was arrested yesterday and in Angola. De Morais was arrested together with friend and business partner Jose Filomeno dos Santos, son of former President Jose Eduardo dos Santos. The two have been placed in detention on suspicion of embezzling national funds over the alleged illegal transfer of $500 million from state coffers to an HSBC Holdings Plc account in the U.K. In a statement, the Angola state prosecutor’s office said,

The evidence gathered resulted in sufficient indications that the defendants have been involved in practices of various crimes including criminal associations, receipt of undue advantage, corruption, participation in unlawful business, money laundering, embezzlement, fraud among others

Mthuli Ncube was the Managing Director and Head of Research Lab at Quantum Global. In January, the company organised and sponsored a business luncheon for President Emmerson Mnangagwa to Meet with investors in Switzerland. Ncube has since resigned from this post.

More: Bloomberg

Frangala

All Star

Bloomberg - Are you a robot?

Nigeria’s Brutal Decision: Former Dictator or Alleged Kleptocrat

Voters need to choose between a pair of uninspiring presidential candidates, neither offering a fix for its struggling economy.

By

Paul Wallace

February 8, 2019 12:01 AM EST

Muhammadu Buhari (left) with Atiku Abubakar in Lagos in 2014. Photographer: Pius Utomi Ekpei/AFP/Getty Images

LISTEN TO ARTICLE

4:56

SHARE THIS ARTICLE

Share

Tweet

Post

Email

What’s a Nigerian citizen to do when there’s a presidential election coming up and the two leading candidates are a former dictator who’s presided over four years of lackluster growth and an alleged kleptocrat of international repute?

This is the choice facing Africa’s largest oil producer, and by some measures its largest economy, in the Feb. 16 vote. Although the field is crowded, incumbent Muhammadu Buhari, 76, faces his strongest challenge from Atiku Abubakar, 72, who served as vice president from 1999 to 2007 and has tried and failed several times already to secure the top job.

Buhari, who led Nigeria briefly in the 1980s as a dictator, came back to power four years ago via the ballot box. After military rule ended in 1999, he contested several elections unsuccessfully before finally becoming the first opposition figure to win the presidency. (He describes himself as a “converted democrat.”) Voters and pundits alike were optimistic that he could diversify the oil-dependent economy, tackle graft, and end Boko Haram’s deadly insurgency. While the stern former general has succeeded in stamping out some of the corruption that’s long blighted Nigeria, critics say he’s been selective, mostly targeting his political opponents. They also say he’s failed on other issues, nicknaming him “Baba Go-Slow” in reference to his age and sluggish response to crises.

Nigeria’s economy is still smaller on a per capita basis than it was in 2014, when it was hammered by the crash in crude prices. Unemployment has surged to a record 23 percent from 6.4 percent at the end of 2014. The stock market has been the world’s worst performer since Buhari came to office, falling more than 50 percent in dollar terms. Boko Haram militants, some affiliated with Islamic State, continue to wreak havoc in the northeast. Other parts of the country have been roiled by a conflict between farmers and herders that’s led to thousands of deaths.

Abubakar, widely known as Atiku, is a father of 26 who has business interests ranging from oil and gas services to food manufacturing. He’s pledged to loosen the state’s grip on the economy, end the naira’s peg to the dollar, and privatize companies including the Nigerian National Petroleum Corp., which dominates the local energy industry. But for all his market-friendly talk—he admires the late Conservative U.K. Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher—many Nigerians think he used his past positions in government to enrich himself.

“It’s like a choice between the devil and the deep blue sea,” says Andrew Niagwan, 36, a teacher in the central city of Jos who doesn’t know if he’ll vote. “Buhari’s got good intentions, but he doesn’t seem very capable. Our living standards have dropped in recent years. As for Atiku, Nigerians are wary because of all the allegations surrounding him.”

U.S. Senate report in 2010 concluded that Abubakar and one of his wives had wired $40 million of “suspect funds” into American accounts and said that his business dealings “raise a host of questions about the nature and source” of his wealth. Although he has denied the claims and has never been indicted at home or abroad, Abubakar hasn’t been able to shake the perception of impropriety. In January he met with lawmakers in Washington after having been banned from the country for more than a decade under a State Department edict against politicians linked to foreign corruption, according to former U.S. officials. (A spokesperson for Abubakar’s campaign denies he’d been banned from the U.S., and the State Department declined to comment on the visit.)

Investors expect Nigerian assets to rise if Abubakar wins. “As much as Buhari has done in terms of tackling corruption, under his guidance the economy has been quite stagnant,” says Christopher Dielmann, an economist at Exotix Capital in London. “The perception is that, under Atiku, a degree of corruption could return to the country, but that might bring with it higher economic growth.”

Still, any bounce could be short-lived. Abubakar may not risk the political fallout from trying to sell state assets or, as he’s also promised, removing a cap that keeps Nigeria’s gasoline prices among the cheapest in the world.

“I’m doubtful there’d be any great change with the economy, no matter who gets elected,” says John Campbell, a former U.S. ambassador to Nigeria who’s now a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations in Washington. That’s a major problem, he says, as the United Nations projects Nigeria’s population will double, to 410 million, by 2050. “How on Earth can you grow an economy fast enough to accommodate those numbers?”

New York-based risk consultant Eurasia Group, which included Nigeria on its list of the top 10 global risks for 2019, predicts Buhari will be reelected. But even if steadier oil prices mean the worst is over, it won’t be an easy four years. “The country might just muddle through for now,” says Amaka Anku, head of Africa at Eurasia. The next election, in 2023, could be an inflection point, she says. “There’s a real chance that a reformist government emerges then.” —With Tope Alake

Nigeria’s Brutal Decision: Former Dictator or Alleged Kleptocrat

Voters need to choose between a pair of uninspiring presidential candidates, neither offering a fix for its struggling economy.

By

Paul Wallace

February 8, 2019 12:01 AM EST

Muhammadu Buhari (left) with Atiku Abubakar in Lagos in 2014. Photographer: Pius Utomi Ekpei/AFP/Getty Images

LISTEN TO ARTICLE

4:56

SHARE THIS ARTICLE

Share

Tweet

Post

What’s a Nigerian citizen to do when there’s a presidential election coming up and the two leading candidates are a former dictator who’s presided over four years of lackluster growth and an alleged kleptocrat of international repute?

This is the choice facing Africa’s largest oil producer, and by some measures its largest economy, in the Feb. 16 vote. Although the field is crowded, incumbent Muhammadu Buhari, 76, faces his strongest challenge from Atiku Abubakar, 72, who served as vice president from 1999 to 2007 and has tried and failed several times already to secure the top job.

Buhari, who led Nigeria briefly in the 1980s as a dictator, came back to power four years ago via the ballot box. After military rule ended in 1999, he contested several elections unsuccessfully before finally becoming the first opposition figure to win the presidency. (He describes himself as a “converted democrat.”) Voters and pundits alike were optimistic that he could diversify the oil-dependent economy, tackle graft, and end Boko Haram’s deadly insurgency. While the stern former general has succeeded in stamping out some of the corruption that’s long blighted Nigeria, critics say he’s been selective, mostly targeting his political opponents. They also say he’s failed on other issues, nicknaming him “Baba Go-Slow” in reference to his age and sluggish response to crises.

Nigeria’s economy is still smaller on a per capita basis than it was in 2014, when it was hammered by the crash in crude prices. Unemployment has surged to a record 23 percent from 6.4 percent at the end of 2014. The stock market has been the world’s worst performer since Buhari came to office, falling more than 50 percent in dollar terms. Boko Haram militants, some affiliated with Islamic State, continue to wreak havoc in the northeast. Other parts of the country have been roiled by a conflict between farmers and herders that’s led to thousands of deaths.

Abubakar, widely known as Atiku, is a father of 26 who has business interests ranging from oil and gas services to food manufacturing. He’s pledged to loosen the state’s grip on the economy, end the naira’s peg to the dollar, and privatize companies including the Nigerian National Petroleum Corp., which dominates the local energy industry. But for all his market-friendly talk—he admires the late Conservative U.K. Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher—many Nigerians think he used his past positions in government to enrich himself.

“It’s like a choice between the devil and the deep blue sea,” says Andrew Niagwan, 36, a teacher in the central city of Jos who doesn’t know if he’ll vote. “Buhari’s got good intentions, but he doesn’t seem very capable. Our living standards have dropped in recent years. As for Atiku, Nigerians are wary because of all the allegations surrounding him.”

U.S. Senate report in 2010 concluded that Abubakar and one of his wives had wired $40 million of “suspect funds” into American accounts and said that his business dealings “raise a host of questions about the nature and source” of his wealth. Although he has denied the claims and has never been indicted at home or abroad, Abubakar hasn’t been able to shake the perception of impropriety. In January he met with lawmakers in Washington after having been banned from the country for more than a decade under a State Department edict against politicians linked to foreign corruption, according to former U.S. officials. (A spokesperson for Abubakar’s campaign denies he’d been banned from the U.S., and the State Department declined to comment on the visit.)

Investors expect Nigerian assets to rise if Abubakar wins. “As much as Buhari has done in terms of tackling corruption, under his guidance the economy has been quite stagnant,” says Christopher Dielmann, an economist at Exotix Capital in London. “The perception is that, under Atiku, a degree of corruption could return to the country, but that might bring with it higher economic growth.”

Still, any bounce could be short-lived. Abubakar may not risk the political fallout from trying to sell state assets or, as he’s also promised, removing a cap that keeps Nigeria’s gasoline prices among the cheapest in the world.

“I’m doubtful there’d be any great change with the economy, no matter who gets elected,” says John Campbell, a former U.S. ambassador to Nigeria who’s now a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations in Washington. That’s a major problem, he says, as the United Nations projects Nigeria’s population will double, to 410 million, by 2050. “How on Earth can you grow an economy fast enough to accommodate those numbers?”

New York-based risk consultant Eurasia Group, which included Nigeria on its list of the top 10 global risks for 2019, predicts Buhari will be reelected. But even if steadier oil prices mean the worst is over, it won’t be an easy four years. “The country might just muddle through for now,” says Amaka Anku, head of Africa at Eurasia. The next election, in 2023, could be an inflection point, she says. “There’s a real chance that a reformist government emerges then.” —With Tope Alake

Last edited:

Secure Da Bag

Veteran

Were these the only two people running for President?