Several hefty economic obstacles will test the government's determination to push ahead with education and health reforms

Harsh financial realities are starting to impinge on the bold programme to modernise the economy, and boost education and health, which swept the new government to power after December's elections. So, in his first state of the nation address on 21 February, President

Nana Addo Dankwa Akufo-Addo pushed ahead with his ambitious agenda for social and economic reform, after first sounding some grave warnings about his government's economic inheritance.

His years as a campaigner and courtroom advocate showed as Akufo-Addo set out his strategy and principles to a packed Parliament. 'Some amongst us seem to be flirting with authoritarianism and romanticising it as an acceptable price to pay to achieve rapid development.' Having won the presidency on his third attempt, Akufo-Addo reiterated his rejection of autocratic methods: 'I have an unshakeable belief in freedom and the democratic process and their capacity to inspire rapid development.'

That will be tested as the government tries to balance the books and reform the creaking state bureaucracy. 'I was not elected by the majority of Ghanaians to complain. I was elected to fix what is broken and my government is determined to do just that,' said the new President. It was a lengthy list (AC Vol 58 No 1,

New order tackles old debts).

An affirmative action programme is to ensure that a third of state jobs be held by women, starting with top government positions. The new Attorney General,

Gloria Akuffo, is to work with Akufo-Addo to set up an independent Special Prosecutor's Office along with a dedicated team of investigators to tackle corruption cases in a non-partisan way, to augment existing organisations such as the Economic and Organised Crime Office.

Making it clear that his pledge to offer free secondary high school education to all Ghanaians was non-negotiable, Akufo-Addo affirmed that this would start with this year's intake of students in September. That could be the signal battle for the President as bankers and policy wonks argue for the plan to be ramped down.

The preceding government under President

John Dramani Mahama allocated 6.5 billion cedis (US$1.4 bn.) for all levels of education out of a total budget of C46.5 bn. yet standards in the state sector have come under increasing fire for poor results. This particularly stings a country that once had one of the highest literacy rates in Africa and Asia.

Meanwhile, a highly profitable system of private schools and universities has grown, pulling in students from across the world. The fees charged are way beyond the reach of the average Ghanaians who expect Akufo-Addo to deliver on his pledge. No detailed figures have emerged for the cost of free secondary education but it will be in the hundreds of millions of cedis.

The Senior Minister,

Yaw Osafo-Maafo, a former Finance Minister, has suggested some education spending could be financed from the state's Heritage fund, the sovereign wealth fund into which the government has to pay a percentage of oil export revenue (

Confidentially Speaking, AC Blog, 24 Jan 2017).

Others are less convinced, arguing that fixing the national finances and hard-headed restructuring should precede more social spending. However, a close ally of the President's told

Africa Confidential: 'Free secondary education for Akufo-Addo is like healthcare for

Obama, he sees it as his legacy and will do it whatever it takes…'. Like

Donald Kaberuka, the

Rwandan former President of the African Development Bank, Akufo-Addo argues that providing high quality education to all citizens is the best means of ending the transmission of poverty from one generation to the next.

The discovery last month of some 7 bn. cedis of unplanned spending by the previous government and a further $2 bn. of debt in the power sector are complicating the balance between the government's pledges and the need to stabilise the economy. Although export earnings from cocoa, gold and oil are due to edge up this year, world prices are far below the commodity boom levels of the past decade. It will be up to the technocrats in the New Patriotic Party government – a cluster of investment bankers, lawyers, and engineers – to fix the finances while making good on their campaign commitments. They are looking for new areas to boost revenue while planning some unpalatable cuts in public spending.

A massive boost to agriculture would form the backbone of the country's economic revival, Akufo-Addo told Parliament. He launched a new national campaign, Planting for Food and Jobs, to transform farming with a coordinated plan to expand extension services massively and boost the distribution of seed and fertiliser. Initially the focus will be on raising the production of rice, corn, soya, sorghum and vegetables. Although it's the world's biggest cocoa producer after neighbouring

Côte d'Ivoire, Ghana currently imports over two-thirds of its staple foods, such as rice and wheat.

The campaign, starting in April, aims to create 750,000 new jobs this year and double that in 2018. Agronomists and other experts say the targets are tough but reckon that well-coordinated investment could create many new jobs from planting and harvesting to processing and transport.

It would also help to reduce inflation; food prices are rising by about 10% a year. A lot of produce is left in the fields because of poor roads and transport. The new Agriculture Minister,

Owusu Afriyie Akoto, says much more use will be made of locally developed high-yielding and drought-resistant seed varieties.

A close ally of Akufo-Addo's, Akoto agrees the agricultural push will also strengthen national finances, both by cutting spending on food imports and by increasing production of cocoa, the biggest cash crop. The government has already raised producer prices for cocoa but will have to do much more to dissuade the thousands of young people working on cocoa farms from quitting and migrating to cities such as Accra, Takoradi and Kumasi.

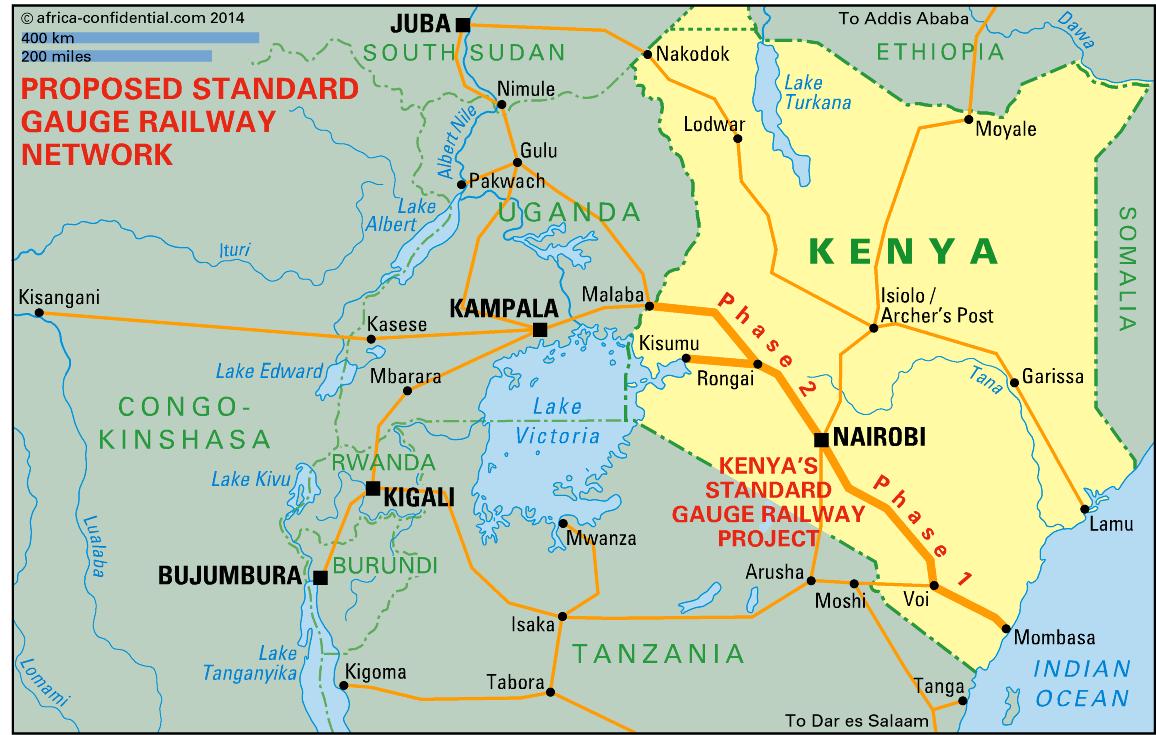

Industrialisation

Akufo-Addo's other big economic theme is industrialisation. The state-owned industries have been in unremitting decline since the heyday of founding President

Kwame Nkrumah, who tried to recycle earnings from cocoa exports into state-backed textile, pharmaceutical, aluminium, vehicle assembly and machine-parts industries. Although a Nkrumahist in his student days, Akufo-Addo now wants a much more limited role for the state, focused on modernising the roads, railways and ports, fixing the chronic power cuts (known in Ghana as

dumsor) and clearing vast expanses of land for industrial parks (AC Vol 57 No 1,

Power cuts may sway polls).

For now, the political mood is bullish. Under its new President, the government got down to work quickly, putting together most of the new ministerial team by the inauguration on 7 January. A few days later, the key appointees went to Parliament for vetting. They are

Ken Ofori-Atta, Finance; Gloria Akuffo, Attorney General;

Alan Kyerematen, Trade and Industry;

Shirley Ayorkor Botchwey, Foreign Affairs; and

Boakye Kyeremateng Agyarko, Energy. With 36 ministers, this is one of Ghana's biggest ever governments, although Treasury officials insist they will come down hard on costs and extra ministers will not mean building more grandiose ministerial offices.

One innovation is to group six ministers in the President's office to deal with railways, business, inner cities, regional decentralisation and development. The Minister for Regional Reorganisation and Development,

Daniel Kwaku Botwe, is to establish four new regions, carved out of the Western, Brong Ahafo, Northern and Volta regions (AC Vol 48 No 24,

Who spends, wins). Also working out of the Presidency, next year Botwe will have to organise referenda in each region – a new region requires 80% electoral support.

As well as fitting in with Akufo-Addo's ideas on decentralising government, the regions are likely to benefit the governing party politically, if they produce more spending and projects at the grassroots. The key reality check on these wide-ranging plans will be

Anthony Akoto-Osei, a former Deputy Finance Minister and economist at the World Bank, who will run the Monitoring and Evaluation Ministry. This key Ministry will also be based in the Presidency.

Alongside these expansive reform plans, Akufo-Addo took Parliament through a grim

tour d'horizon of the economy. It grew last year at 3.6%, its slowest rate since 1990. During the last eight years of National Democratic Congress governments, the national debt had risen from C9.5 bn. to C122 bn., about 74% of gross domestic product.

Most problematic, said Akufo-Addo, was the budget deficit of 10.2% of GDP last year: that is almost twice the 5.3% target that the outgoing Finance Minister,

Seth Terkper, had agreed with the International Monetary Fund. That includes some C7 bn. in arrears and outstanding payments that circumvented IMF scrutiny. Less than three months before the elections on

7 December, the Fund's Executive Board had judged that the government's implementation of its reform programme was 'broadly satisfactory'.

The failure of these safeguards has prompted Senior Minister Osafo-Maafo to propose a review of the $918 million programme with the IMF, which is due to wind up in April 2018. The targets are likely to be revised and the programme extended until the end of next year at least.

Bold policies

On the IMF mission's departure from Ghana on 10 February, team leader

Joël Toujas-Bernaté said the government would have to adopt bold policies to reduce the budget deficit and manage the ballooning debt servicing costs. He acknowledged that there had been 'large fiscal slippages'. Presumably these had escaped the attention of last year's IMF missions because they bypassed the public finance management system. Toujas-Bernaté welcomed the government's decision to audit all outstanding obligations inherited from its predecessor.

After discussions with Finance Minister Ofori-Atta, who was due to present his first budget on 2 March, Toujas-Bernaté also applauded the government's planned reforms, which would cut tax exemptions and boost tax compliance. Although the IMF delegation leader praised the Bank of Ghana's monetary policy for 'mitigating inflationary pressures' and actions against non-performing loans, the financial position of several banks has deteriorated gravely. The Bank's own figures show that non-performing loans were up to 17.3% of the banks' assets by December 2016, from 11.2% in May 2015.

Addressing this litany of woes, Ofori-Atta's first priority will be to restructure the country's debt, domestic and foreign, to reduce servicing costs. This should give him a little more space to cut some taxes and tariffs that he argues are holding back growth. This year, Ofori-Atta, a former investment banker, will have the most politically testing job, trying to adapt policies and spending to the new financial realities.