You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The A.I Megathread (LLM , GPT , Development)

More options

Who Replied?

October 31, 2023

One of the Phind Model's key advantages is that's very fast. We've been able to achieve a 5x speedup over GPT-4 by running our model on H100s using the new TensorRT-LLM library from NVIDIA, reaching 100 tokens per second single-stream.

Another key advantage of the Phind Model is context – it supports up to 16k tokens. We currently allow inputs of up to 12k tokens on the website and reserve the remaining 4k for web results.

There are still some rough edges with the Phind Model and we'll continue improving it constantly. One area where it still suffers is consistency — on certain challenging questions where it is capable of getting the right answer, the Phind Model might take more generations to get to the right answer than GPT-4.

www.phind.com

www.phind.com

news.ycombinator.com

news.ycombinator.com

Phind Model beats GPT-4 at coding, with GPT-3.5-like speed and 16k context

We're excited to announce that Phind now defaults to our own model that matches and exceeds GPT-4's coding abilities while running 5x faster. You can now get high quality answers for technical questions in 10 seconds instead of 50.

The current 7th-generation Phind Model is built on top of our open-source CodeLlama-34B fine-tunes that were the first models to beat GPT-4's score on HumanEval and are still the best open source coding models overall by a wide margin.- The Phind Model V7 achieves 74.7% pass@1 on HumanEval

One of the Phind Model's key advantages is that's very fast. We've been able to achieve a 5x speedup over GPT-4 by running our model on H100s using the new TensorRT-LLM library from NVIDIA, reaching 100 tokens per second single-stream.

Another key advantage of the Phind Model is context – it supports up to 16k tokens. We currently allow inputs of up to 12k tokens on the website and reserve the remaining 4k for web results.

There are still some rough edges with the Phind Model and we'll continue improving it constantly. One area where it still suffers is consistency — on certain challenging questions where it is capable of getting the right answer, the Phind Model might take more generations to get to the right answer than GPT-4.

Phind: AI search engine

Get instant answers, explanations, and examples for all of your technical questions.

Phind Model beats GPT-4 at coding, with GPT-3.5 speed and 16k context | Hacker News

Last edited:

TikTok, Snapchat and others sign pledge to tackle AI-generated child sex abuse images

Story by Reuters • 1d

FILE PHOTO: TikTok app logo is seen in this illustration taken, August 22, 2022. REUTERS/Dado Ruvic/Illustration/File Photo© Thomson Reuters

LONDON (Reuters) - Tech firms including TikTok, Snapchat and Stability AI have signed a joint statement pledging to work together to counter child sex abuse images generated by artificial intelligence.

Britain announced the joint statement - which also listed the United States, German and Australian governments among its 27 signatories - at an event on Monday being held in the run up to a global summit hosted by the UK on AI safety this week.

"We resolve to sustain the dialogue and technical innovation around tackling child sexual abuse in the age of AI," the statement read.

"We resolve to work together to ensure that we utilise responsible AI for tackling the threat of child sexual abuse and commit to continue to work collaboratively to ensure the risks posed by AI to tackling child sexual abuse do not become insurmountable."

FILE PHOTO: Snapchat logo is seen in this illustration taken July 28, 2022. REUTERS/Dado Ruvic/Illustration/File Photo© Thomson Reuters

Britain cited data from the Internet Watch Foundation showing that in one dark web forum users had shared nearly 3,000 images AI generated child sexual abuse material.

"It is essential, now, we set an example and stamp out the abuse of this emerging technology before it has a chance to fully take root," said IWF chief executive Susie Hargreaves.

(Reporting by William James; editing by Sarah Young)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25044607/236892_Golnar_Khosrowshahi_Reservoir_Founder_CEO_WJoel.jpg)

AI is on a collision course with music — Reservoir’s Golnar Khosrowshahi thinks there’s a way through

The music industry and its fragile business models are under pressure from AI. But it’s far from hopeless.

The Tech That’s Radically Reimagining the Public Sphere

Story by Jesse Barron • 28m

The Tech That’s Radically Reimagining the Public Sphere© Illustration by Ben Kothe / The Atlantic. Source: Getty.

Facial recognition was a late-blooming technology: It went through 40 years of floundering before it finally matured. At the 1970 Japan World Exposition, a primitive computer tried—mostly in vain—to match visitors with their celebrity look-alikes. In 2001, the first-ever “smart” facial-recognition surveillance system was deployed by the police department in Tampa, Florida, where it failed to make any identifications that led to arrests. At a meeting in Washington, D.C., in 2011, an Intel employee tried to demonstrate a camera system that could distinguish male faces from female ones. A woman with shoulder-length red hair came up from the audience. The computer rendered its verdict: male.

Facial recognition was hard, for two reasons. Teaching a computer to perceive a human face was trouble enough. But matching that face to the person’s identity in a database was plainly fanciful—it required significant computing power, and quantities of photographs tied to accurate data. This prevented widespread adoption, because matching was always going to be where the money was. In place of facial-recognition technology (FRT), other biometrics, such as fingerprinting and retinal scanning, came to market. The face-matching problem hadn’t been cracked.

Or so everybody thought, until a pair of researchers from the nonprofits MuckRock and Open the Government made a discovery. They had been sending Freedom of Information Act requests around the country, trying to see whether police departments were using the technology in secret. In 2019, the Atlanta Police Department responded to one of those FOIAs with a bombshell: a memo from a mysterious company called Clearview AI, which had a cheap-looking website yet claimed to have finally solved the problem of face-matching, and was selling the technology to law enforcement for a few thousand dollars a year. The researchers sent their findings to a reporter at The New York Times, Kashmir Hill, who introduced readers to Clearview in a 2020 scoop.

Hill’s new book, Your Face Belongs to Us, provides a sharply reported history of how Clearview came to be, who invested in it, and why a better-resourced competitor like Facebook or Amazon didn’t beat this unknown player to the market. The saga is colorful, and the characters come off as flamboyant villains; it’s a fun read. But the book’s most incisive contribution may be the ethical question it raises, which will be at the crux of the privacy debate about facial-recognition technology for many years to come. We have already willingly uploaded our private lives online, including to companies that enthusiastically work with law enforcement. What does consent, or opting out, look like in this context? A relative bit player made these advances. The rewriting of our expectations regarding privacy requires more complex, interlacing forces—and our own participation.

[Read: The Atlantic’s guide to privacy]

Hill’s book begins about five years after Intel presented its useless facial-recognition tech in Washington, but it might as well be a century later, so dramatically has the technology improved. It’s 2016, and the face-matching problem is no longer daunting. Neural nets—basically, artificial-intelligence systems that are capable of “deep learning” to improve their function—have conquered facial recognition. In some studies, they can even distinguish between identical twins. All they need is photographs of faces on which to train themselves—billions of them, attached to real identities. Conveniently, billions of us have created such a database, in the form of our social-media accounts. Whoever can set the right neural net loose on the right database of faces can create the first face-matching technology in history. The atoms are lying there waiting for the Oppenheimer who can make them into a bomb.

Hill’s Oppenheimer is Hoan Ton-That, a Vietnamese Australian who got his start making Facebook quiz apps (“Have you ever … ?” “Would you rather … ?”) along with an “invasive, potentially illegal” viral phishing scam called ViddyHo. When ViddyHo got him ostracized from Silicon Valley, Ton-That reached out to a man named Charles Johnson, an alt-right gadfly whose websites served empirically dubious hot takes in the mid-2010s: Barack Obama is gay, Michael Brown provoked his own murder, and so on. Rejected by the liberal corporate circles in which he once coveted membership, Ton-That made a radical rightward shift.

The story of Ton-That and Johnson follows a familiar male-friendship arc. By the end, they will be archrivals: Ton-That will cut Johnson out of their business, and Johnson will become an on-the-record source for Hill. But at first, they’re friends and business partners: They agree that it would be awesome if they built a piece of software that could, for example, screen known left-wingers to keep them out of political conventions—that is, a face-matching facial-recognition program.

To build one, they first needed to master neural-net AI. Amazingly, neural-net code and instructions were available for free online. The reason for this goes back to a major schism in AI research: For a long time, the neural-net method, whereby the computer teaches itself, was considered impossible, whereas the “symbolic” method, whereby humans teach the computer step-by-step, was embraced. Finding themselves cast out, neural-net engineers posted their ideas on the internet, waiting for the day when computers would become powerful enough to prove them right. This explains why Ton-That was able to access neural-net code so easily. In 2016, he hired engineers to help him refashion it for his purposes. “It’s going to sound like I googled ‘Flying car’ and then found instructions on it,” he worries to Hill (she managed to get Ton-That to speak to her on the record for the book).

But even with a functioning neural net, there was still the issue of matching. Starting with Venmo—which had the weakest protections for profile pictures—Ton-That gobbled up photos from social-media sites. Soon he had a working prototype; $200,000 from the venture capitalist Peter Thiel, to whom Johnson had introduced him; meetings with other VCs; and, ultimately, a multibillion-picture database. Brilliantly, Ton-That made sure to scrape Crunchbase, a database of important players in venture capital, so that Clearview would always work properly on the faces of potential investors. There are no clear nationwide privacy laws about who can use facial recognition and how (though a handful of states have limited the practice). Contracts with police departments followed.

Proponents of FRT have always touted its military and law-enforcement applications. Clearview, for instance, reportedly helped rescue a child victim of sexual abuse by identifying their abuser in the grainy background of an Instagram photo, which led police to his location. But publicizing such morally black-and-white stories has an obvious rhetorical advantage. As one NYPD officer tells Hill, “With child exploitation or kidnapping, how do you tell someone that we have a good picture of this guy and we have a system that could identify them, but due to potential bad publicity, we’re not going to use it to find this guy?”

One possible counterargument is that facial-recognition technology is not just a really good search engine for pictures. It’s a radical reimagining of the public sphere. If widely adopted, it will further close the gap between our lives in physical reality and our digital lives. This is an ironic slamming-shut of one of the core promises of the early days of the internet: the freedom to wander without being watched, the chance to try on multiple identities, and so on. Facial recognition could bind us to our digital history in an inescapable way, spelling the end of what was previously a taken-for-granted human experience: being in public anonymously.

Most people probably don’t want that to happen. Personally, if I could choose to opt out of having my image in an FRT database, I would do so emphatically. But opting out is tricky. Despite my well-reasoned fears about the surveillance state, I am basically your average dummy when it comes to sharing my life with tech firms. This summer, before my son was born, it suddenly felt very urgent to learn exactly what percentage Ashkenazi Jewish he would be, so I gave my DNA to 23andMe, along with my real name and address (I myself am 99.9 percent Ashkenazi, it turned out). This is just one example of how I browse the internet like a sheep to the slaughter. A hundred times a day, I unlock my iPhone with my face. My image and name are associated with my X (formerly Twitter), Uber, Lyft, and Venmo accounts. Google stores my personal and professional correspondence. If we are hurtling toward a future in which a robot dog can accost me on the street and instantly connect my face to my family tree, credit score, and online friends, consider me horrified, but I can’t exactly claim to be shocked: I’ve already provided the raw material for this nightmare scenario in exchange for my precious consumer conveniences.

In her 2011 book, Our Biometric Future, the scholar Kelly Gates noted the nonconsensual aspect of facial-recognition technology. Even if you don’t like your fingerprints being taken, you know when it’s happening, whereas cameras can shoot you secretly at a sporting event or on a street corner. This could make facial recognition more ethically problematic than the other biometric-data gathering. What Gates could not have anticipated was the ways in which social media would further muddle the issue, because consent now happens in stages: We give the images to Instagram and TikTok, assuming that they won’t be used by the FBI but not really knowing whether they could be, and in the meantime enjoy handy features, such as Apple Photos’ sorting of pictures by which friends appear in them. Softer applications of the technology are already prevalent in everyday ways, whether Clearview is in the picture or not.

[Read: Stadiums have gotten downright dystopian]

After Hill exposed the company, it decided to embrace the publicity, inviting her to view product demos, then posting her articles on the “Media” section of its website. This demonstrates Clearview’s cocky certainty that privacy objections can ultimately be overridden. History suggests that such confidence may not be misplaced. In the late 1910s, when passport photos were introduced, many Americans bristled, because the process reminded them of getting a mugshot taken. Today, nobody would think twice about going to the post office for a passport photo. Though Hill’s reporting led to an ACLU lawsuit that prevented Clearview from selling its tech to private corporations and individuals, the company claims to have thousands of contracts with law-enforcement agencies, including the FBI, which will allow it to keep the lights on while it figures out the next move.

Major Silicon Valley firms have been slow to deploy facial recognition commercially. The limit is not technology; if Ton-That could build Clearview literally by Googling, you can be sure that Google can build a better product. The legacy firms claim that they’re restrained, instead, by their ethical principles. Google says that it decided not to make general-purpose FRT available to the public because the company wanted to work out the “policy and technical issues at stake.” Amazon, Facebook, and IBM have issued vague statements saying that they have backed away from FRT research because of concerns about privacy, misuse, and even racial bias, as FRT may be less accurate on darker-skinned faces than on lighter-skinned ones. (I have a cynical suspicion that the firms’ concern regarding racial bias will turn out to be a tactic. As soon as the racial-bias problem is solved by training neural nets on more Black and brown faces, the expansion of the surveillance dragnet will be framed as a victory for civil rights.)

Now that Clearview is openly retailing FRT to police departments, we’ll see whether the legacy companies hold so ardently to their scruples. With an early entrant taking all the media heat and absorbing all the lawsuits, they may decide that the time is right to enter the race. If they do, the next generation of facial-recognition technology will improve upon the first; the ocean of images only gets deeper. As one detective tells Hill, “This generation posts everything. It’s great for police work.”

Former Google CEO Eric Schmidt Bets AI Will Shake Up Scientific Research

Story by Jackie Davalos, Nate Lanxon and David Warren • 1h(Bloomberg) -- Eric Schmidt is funding a nonprofit that’s focused on building an artificial intelligence-powered assistant for the laboratory, with the lofty goal of overhauling the scientific research process, according to interviews with the former Google CEO and officials at the new venture.

The nonprofit, Future House, plans to develop AI tools that can analyze and summarize research papers as well as respond to scientific questions using large language models — the same technology that supports popular AI chatbots. But Future House also intends to go a step further.

The “AI scientist,” as Future House refers to it, will one day be able to sift through thousands of scientific papers and independently compose hypotheses at greater speed and scale than humans, Chief Executive Officer Sam Rodriques said on the latest episode of the Bloomberg Originals series AI IRL, his most extensive comments to date on the company.

A growing number of businesses and investors are focusing on AI’s potential applications in science, including uncovering new medicines and therapies. While Future House aims to make breakthroughs of its own, it believes the scientific process itself can be transformed by having AI generate a hypothesis, conduct experiments and reach conclusions — even though some existing AI tools have been prone to errors and bias.

Rodriques acknowledged the risks of AI being applied in science. "It's not just inaccuracy that you need to worry about,” he said. There are also concerns that “people can use them to come up with weapons and things like that.” Future House will "have an obligation" to make sure there's safeguards in place,” he added.

Eric Schmidt© Bloomberg

In an interview, Schmidt said early-stage scientific research “is not moving fast enough today.” Schmidt helped shape the idea behind Future House and was inspired by his time at Xerox’s Palo Alto Research Center, which developed ethernet, laser printing and other innovations.

“It was a place where you got these people in their late 20s and early 30s, gave them independence and all the resources they needed, and they would invent things at a pace that you didn't get anywhere else,” Schmidt said. “What I really want is to create new environments like what PARC used to be, where outstanding young researchers can pursue their best ideas.”

Schmidt has an estimated net worth of $24.5 billion, according to the Bloomberg Billionaires Index. He’s funneled some of that fortune into philanthropic efforts like Schmidt Futures, an initiative that funds science and technology entrepreneurs. In recent months, he’s emerged as an influential voice on AI policy in Washington.

Rodriques, a biotechnology inventor who studied at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, said Schmidt will fund Future House for its first five years. He estimated that the non-profit will spend about $20 million by the end of 2024. After that, “it will depend on how we grow and what we need,” he said, adding that a substantial portion of that cash will go to hiring talent and setting up what’s called a “wet” laboratory, a space designed to test chemicals and other biological matter. While Schmidt is providing most of the upfront capital, Future House is also in talks with other philanthropic backers, Rodriques said.

“The key thing about Future House is that we are getting together this biology talent and this AI talent in a way that you don't get in other places,” Schmidt said.

One of the first hires is Andrew White, the nonprofit’s head of science, who was most recently an associate professor of chemical engineering at the University of Rochester. “I think most scientists probably read five papers a week. Imagine what's going to happen when you have systems that can process all 10,000 papers that are coming out every day,” White said. “In some fields, the limiting factor is not the equipment. It's not really the cost. It's the ability of humans to come up with the next experiment.”

Future House will start with biology but its system will eventually be applicable to other scientific fields, White said.

With his financial backing, Schmidt believes Future House will be able to prioritize research rather than racing to make money. “I think getting the incentives right is especially important right now, when there’s a very high expectation that progress in AI will lead to products in the short term, which is leading a lot of the big AI research centers to focus very much on commercialization over research,” Schmidt said.

Watch the full episode of AI IRL now or catch up on all previous episodes .

Javi Lopez

@javilopen

22h

22h

First of all, would you like to play the game?

Here's a link! (Currently, it doesn't work on mobile): https://bestaiprompts.art/angry-pumpkins/index.html

If you read the text below the game screen, which provides explanations, you'll see how you can create your own levels and play them!

Javi Lopez

@javilopen

22h

22h

Introduction

Introduction

I have to admit, I'm genuinely blown away. Honestly, I never thought this would be possible. I truly believe we're living in a historic moment that we've only seen in sci-fi movies up until now.

These new work processes, where we can create anything using just natural language, are going to change the world as we know it.

It's such a massive tidal wave that those who don't see it coming will be hit hard.

So... let's start riding the wave!

Javi Lopez

@javilopen

22h

22h

Graphics

Graphics

This was the easiest part, after all, I've been generating images with AI for over a year and a half Here are all the prompts for your enjoyment!

Here are all the prompts for your enjoyment!

Title Screen (DALL·E 3 from GPT-4)

Title Screen (DALL·E 3 from GPT-4)

- "Photo of a horizontal vibrant home screen for a video game titled 'Angry Pumpkins'. The design is inspired by the 'Angry Birds' game aesthetic but different. Halloween elements like haunted houses, gravestones, and bats dominate the background. The game logo is prominently displayed at the center-top, with stylized pumpkin characters looking angry and ready for action on either side. A 'Play' button is located at the bottom center, surrounded by eerie mist."

Backgrounds (Midjourney)

Backgrounds (Midjourney)

I used one image for the background (with several inpaintings):

- "Angry birds skyline in iPhone screenshot, Halloween Edition, graveyard, in the style of light aquamarine and orange, neo-traditionalist, kerem beyit, earthworks, wood, Xbox 360 graphics, light pink and navy --ar 8:5"

And another, cropped, for the ground:

- "2d platform, stone bricks, Halloween, 2d video game terrain, 2d platformer, Halloween scenario, similar to angry birds, metal slug Halloween, screenshot, in-game asset --ar 8:5"

Characters (Midjourney)

Characters (Midjourney)

- "Halloween pumpkin, in-game sprite but Halloween edition, simple sprite, 2d, white background"

- "Green Halloween monster, silly, amusing, in-game sprite but Halloween edition, simple sprite, 2d, white background"

Objects (Midjourney)

Objects (Midjourney)

I created various "sprite stylesheets" and then cropped and removed the background using Photoshop/Photopea. For small details, I used the inpainting of Midjourney.

- "Wooden box. Item assets sprites. White background. In-game sprites"

- "Skeleton bone. Large skeleton bone. Item assets sprites. White background. In-game sprites"

- "Rectangular stone. Item assets sprites. White background. In-game sprites"

- "Wooden box. Large skeleton bone. Item assets sprites. White background. In-game sprites"

- "Item assets sprites. Wooden planks. White background. In-game sprites. Similar to Angry Birds style"

Javi Lopez

@javilopen

22h

22h

Programming (GPT-4)

Programming (GPT-4)

Full source code here: https://bestaiprompts.art/angry-pumpkins/sketch.js

Full source code here: https://bestaiprompts.art/angry-pumpkins/sketch.js

Although the game is just 600 lines of which I haven't written ANY, this was the most challenging part. As you can see, I got into adding many details like different particle effects, different types of objects, etc. And to this day, we're still not at a point where GPT-4 can generate an entire game with just a prompt. But I have no doubt that in the future we'll be able to create triple AAA video games just by asking for it.

Anyway, back to the present, the TRICK is to request things from GPT-4 iteratively. Actually, very similar to how a person would program it: Starting with a simple functional base and iterate, expand, and improve the code from there.

Let's see some tricks and prompts I used:

Start with something simple

Start with something simple

- "Can we now create a simple game using matter.js and p5.js in the style of "Angry Birds"? Just launch a ball with angle and force using the mouse and hit some stacked boxes with 2D physics.

And from there, keep asking for more and more things. And every time something goes wrong, clearly explain the mistake and let it fix it. Patience! Examples:

And from there, keep asking for more and more things. And every time something goes wrong, clearly explain the mistake and let it fix it. Patience! Examples:

- "Now, I ask you: do you know how the birds are launched in Angry Birds? What the finger does on the screen? Exactly. Add this to the game, using the mouse."

- "I have this error, please, fix it: Uncaught ReferenceError: Constraint is not defined"

- "I would like to make a torch with particle effects. Can it be done with p5.js? Make one, please."

- "Now, make the monsters circular, and be very careful: apply the same technique that already exists for the rectangular ones regarding scaling and collision area, and don't mess it up like before. "

"

This part took us (GTP-4 and me) many iterations and patience.

This part took us (GTP-4 and me) many iterations and patience.

- "There's something off with the logic that calculates when there's a strong impact on a bug. If the impact is direct, it works well, but not if it's indirect. For example, if I place a rectangle over two bugs and drop a box on the rectangle, even though the bugs should be affected by the impact, they don't notice it. What can we do to ensure they also get affected when things fall on top of a body they are under?"

@javilopen

22h

22h

First of all, would you like to play the game?

Here's a link! (Currently, it doesn't work on mobile): https://bestaiprompts.art/angry-pumpkins/index.html

If you read the text below the game screen, which provides explanations, you'll see how you can create your own levels and play them!

Javi Lopez

@javilopen

22h

22h

I have to admit, I'm genuinely blown away. Honestly, I never thought this would be possible. I truly believe we're living in a historic moment that we've only seen in sci-fi movies up until now.

These new work processes, where we can create anything using just natural language, are going to change the world as we know it.

It's such a massive tidal wave that those who don't see it coming will be hit hard.

So... let's start riding the wave!

Javi Lopez

@javilopen

22h

22h

This was the easiest part, after all, I've been generating images with AI for over a year and a half

Here are all the prompts for your enjoyment!

Here are all the prompts for your enjoyment!- "Photo of a horizontal vibrant home screen for a video game titled 'Angry Pumpkins'. The design is inspired by the 'Angry Birds' game aesthetic but different. Halloween elements like haunted houses, gravestones, and bats dominate the background. The game logo is prominently displayed at the center-top, with stylized pumpkin characters looking angry and ready for action on either side. A 'Play' button is located at the bottom center, surrounded by eerie mist."

I used one image for the background (with several inpaintings):

- "Angry birds skyline in iPhone screenshot, Halloween Edition, graveyard, in the style of light aquamarine and orange, neo-traditionalist, kerem beyit, earthworks, wood, Xbox 360 graphics, light pink and navy --ar 8:5"

And another, cropped, for the ground:

- "2d platform, stone bricks, Halloween, 2d video game terrain, 2d platformer, Halloween scenario, similar to angry birds, metal slug Halloween, screenshot, in-game asset --ar 8:5"

- "Halloween pumpkin, in-game sprite but Halloween edition, simple sprite, 2d, white background"

- "Green Halloween monster, silly, amusing, in-game sprite but Halloween edition, simple sprite, 2d, white background"

I created various "sprite stylesheets" and then cropped and removed the background using Photoshop/Photopea. For small details, I used the inpainting of Midjourney.

- "Wooden box. Item assets sprites. White background. In-game sprites"

- "Skeleton bone. Large skeleton bone. Item assets sprites. White background. In-game sprites"

- "Rectangular stone. Item assets sprites. White background. In-game sprites"

- "Wooden box. Large skeleton bone. Item assets sprites. White background. In-game sprites"

- "Item assets sprites. Wooden planks. White background. In-game sprites. Similar to Angry Birds style"

Javi Lopez

@javilopen

22h

22h

Although the game is just 600 lines of which I haven't written ANY, this was the most challenging part. As you can see, I got into adding many details like different particle effects, different types of objects, etc. And to this day, we're still not at a point where GPT-4 can generate an entire game with just a prompt. But I have no doubt that in the future we'll be able to create triple AAA video games just by asking for it.

Anyway, back to the present, the TRICK is to request things from GPT-4 iteratively. Actually, very similar to how a person would program it: Starting with a simple functional base and iterate, expand, and improve the code from there.

Let's see some tricks and prompts I used:

- "Can we now create a simple game using matter.js and p5.js in the style of "Angry Birds"? Just launch a ball with angle and force using the mouse and hit some stacked boxes with 2D physics.

- "Now, I ask you: do you know how the birds are launched in Angry Birds? What the finger does on the screen? Exactly. Add this to the game, using the mouse."

- "I have this error, please, fix it: Uncaught ReferenceError: Constraint is not defined"

- "I would like to make a torch with particle effects. Can it be done with p5.js? Make one, please."

- "Now, make the monsters circular, and be very careful: apply the same technique that already exists for the rectangular ones regarding scaling and collision area, and don't mess it up like before.

- "There's something off with the logic that calculates when there's a strong impact on a bug. If the impact is direct, it works well, but not if it's indirect. For example, if I place a rectangle over two bugs and drop a box on the rectangle, even though the bugs should be affected by the impact, they don't notice it. What can we do to ensure they also get affected when things fall on top of a body they are under?"

Last edited:

What the executive order means for openness in AI

Good news on paper, but the devil is in the details

What the executive order means for openness in AI

Good news on paper, but the devil is in the details

ARVIND NARAYANAN

AND

SAYASH KAPOOR

OCT 31, 2023

Share

By Arvind Narayanan, Sayash Kapoor, and Rishi Bommasani.

The Biden-Harris administration has issued an executive order on artificial intelligence. It is about 20,000 words long and tries to address the entire range of AI benefits and risks. It is likely to shape every aspect of the future of AI, including openness: Will it remain possible to publicly release model weights while complying with the EO’s requirements? How will the EO affect the concentration of power and resources in AI? What about the culture of open research?

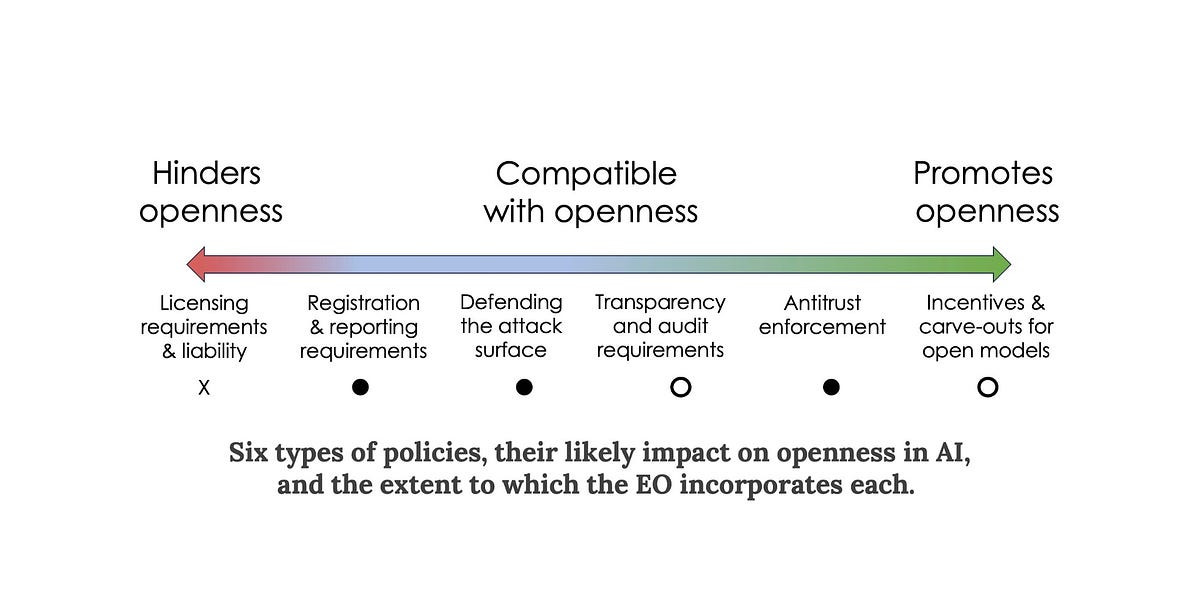

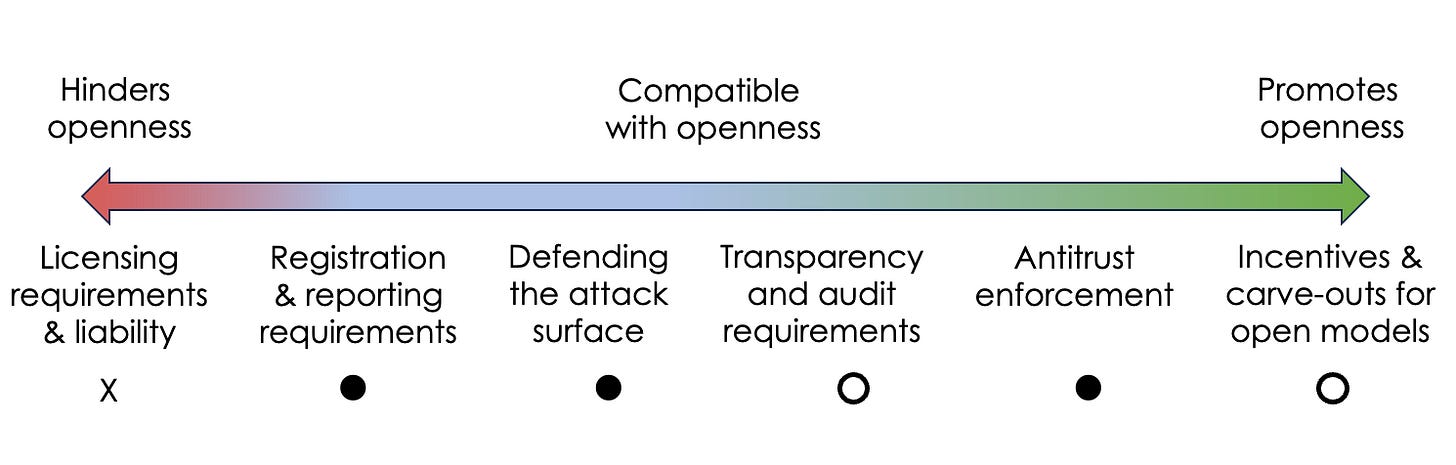

We cataloged the space of AI-related policies that might impact openness and grouped them into six categories. The EO includes provisions from all but one of these categories. Notably, it does not include licensing requirements. On balance, the EO seems to be good news for those who favor openness in AI.

But the devil is in the details. We will know more as agencies start implementing the EO. And of course, the EO is far from the only policy initiative worldwide that might affect AI openness.1

Six types of policies, their likely impact on openness in AI, and the extent to which the EO incorporates each.

Licensing and liability

Licensing proposals aim to enable government oversight of AI by allowing only certain licensed companies and organizations to build and release state-of-the-art AI models. We are skeptical of licensing as a way of preventing the release of harmful AI: As the cost of training a model to a given capability level decreases, it will require increasingly draconian global surveillance to enforce.

Liability is closely related: The idea is that the government can try to prevent harmful uses by making model developers responsible for policing their use.

Both licensing and liability are inimical to openness. Sufficiently serious liability would amount to a ban on releasing model weights.2 Similarly, requirements to prevent certain downstream uses or to ensure that all generated content is watermarked would be impossible to satisfy if the weights are released.

Fortunately, the EO does not contain licensing or liability provisions. It doesn’t mention artificial general intelligence or existential risks, which have often been used as an argument for these strong forms of regulation.

The EO launches a public consultation process through the Department of Commerce to understand the benefits and risks of foundation models with publicly available weights. Based on this, the government will consider policy options specific to such models.

Registration and reporting

The EO does include a requirement to report to the government any AI training runs that are deemed large enough to pose a serious security risk.3 And developers must report various other details including the results of any safety evaluation (red-teaming) that they performed. Further, cloud providers need to inform the government when a foreign person attempts to purchase computational services that suffice to train a large enough model.

It remains to be seen how useful the registry will be for safety. It will depend in part on whether the compute threshold (any training run involving over 1026 mathematical operations is covered) serves as a good proxy for potential risk, and whether the threshold can be replaced with a more nuanced determination that evolves over time.

One obvious limitation is that once a model is openly released, fine tuning can be done far more cheaply, and can result in a model with very different behavior. Such models won’t need to be registered. There are many other potential ways for developers to architect around the reporting requirement if they chose to.4

In general, we think it is unlikely that a compute threshold or any other predetermined criterion can effectively anticipate the riskiness of individual models. But in aggregate, the reporting requirement could give the government a better understanding of the landscape of risks.

The effects of the registry will also depend on how it is used. On the one hand it might be a stepping stone for licensing or liability requirements. But it might also be used for purposes more compatible with openness, which we discuss below.

The registry itself is not a deal breaker for open foundation models. All open models to date fall well below the compute threshold of 1026 operations. It remains to be seen if the threshold will stay frozen or change over time.

If the reporting requirements prove to be burdensome, developers will naturally try to avoid them. This might lead to a two-tier system for foundation models: frontier models whose size is unconstrained by regulation and sub-frontier models that try to stay just under the compute threshold to avoid reporting.

Defending attack surfaces

One possible defense against malicious uses of AI is to try to prevent bad actors from getting access to highly capable AI. We don’t think this will work. Another approach is to enumerate all the harmful ways in which such AI might be used, and to protect each target. We refer to this as defending attack surfaces. We have strongly advocated for this approach in our inputs to policy makers.

The EO has a strong and consistent emphasis on defense of attack surfaces, and applies it across the spectrum of risks identified: disinformation, cybersecurity, bio risk, financial risk, etc. To be clear, this is not the only defensive strategy that it adopts. There is also a strong focus on developing alignment methods to prevent models from being used for offensive purposes. Model alignment is helpful for closed models but less so for open models since bad actors can fine tune away the alignment.

Notable examples of defending attack surfaces:

The EO calls for methods to authenticate digital content produced by the federal government. This is a promising strategy. We think the big risk with AI-generated disinformation is not that people will fall for false claims — AI isn’t needed for that — but that people will stop trusting true information (the "liar's dividend"). Existing authentication and provenance efforts suffer from a chicken-and-egg problem, which the massive size of the federal government can help overcome.

It calls for the use of AI to help find and fix cybersecurity vulnerabilities in critical infrastructure and networks. Relatedly, the White House and DARPA recently launched a $20 million AI-for-cybersecurity challenge. This is spot on. Historically, the availability of automated vulnerability-discovery tools has helped defenders over attackers, because they can find and fix bugs in their software before shipping it. There’s no reason to think AI will be different. Much of the panic around AI has been based on the assumption that attackers will level-up using AI while defenders will stand still. The EO exposes the flaws of that way of thinking.

It calls for labs that sell synthetic DNA and RNA to better screen their customers. It is worth remembering that biological risks exist in the real world, and controlling the availability of materials may be far more feasible than controlling access to AI. These risks are already serious (for example, malicious actors already know how to create anthrax) and we already have ways to mitigate them, such as customer screening. We think it’s a fallacy to reframe existing risks (disinformation, critical infrastructure, bio risk) as AI risks. But if AI fears provide the impetus to strengthen existing defenses, that’s a win.

{continued}

Transparency and auditing

There is a glaring absence of transparency requirements in the EO — whether pre-training data, fine-tuning data, labor involved in annotation, model evaluation, usage, or downstream impacts. It only mentions red-teaming, which is a subset of model evaluation.

This is in contrast to another policy initiative also released yesterday, the G7 voluntary code of conduct for organizations developing advanced AI systems. That document has some emphasis on transparency.

Antitrust enforcement

The EO tasks federal agencies, in particular the Federal Trade Commission, with promoting competition in AI. The risks it lists include concentrated control of key inputs, unlawful collusion, and dominant firms disadvantaging competitors.

What specific aspects of the foundation model landscape might trigger these concerns remains to be seen. But it might include exclusive partnerships between AI companies and big tech companies; using AI functionality to reinforce walled gardens; and preventing competitors from using the output of a model to train their own. And if any AI developer starts to acquire a monopoly, that will trigger further concerns.

All this is good news for openness in the broader sense of diversifying the AI ecosystem and lowering barriers to entry.

Incentives for AI development

The EO asks the National Science Foundation to launch a pilot of the National AI Research Resource (NAIRR). The idea began as Stanford’s National Research Cloud proposal and has had a long journey to get to this point. NAIRR will foster openness by mitigating the resource gap between industry and academia in AI research.

Various other parts of the EO will have the effect of increasing funding for AI research and expanding the pool of AI researchers through immigration reform.5 (A downside of prioritizing AI-related research funding and immigration is increasing the existing imbalance among different academic disciplines. Another side effect is hastening the rebranding of everything as AI in order to qualify for special treatment, making the term AI even more meaningless.)

While we welcome the NAIRR and related parts of the EO, we should be clear that it falls far short of a full-throated commitment to keeping AI open. The North star would be a CERN style, well-funded effort to collaboratively develop open (and open-source) foundation models that can hold their own against the leading commercial models. Funding for such an initiative is probably a long shot today, but is perhaps worth striving towards.

What comes next?

We have described only a subset of the provisions in the EO, focusing on those that might impact openness in AI development. But it has a long list of focus areas including privacy and discrimination. This kind of whole-of-government effort is unprecedented in tech policy. It is a reminder of how much can be accomplished, in theory, with existing regulatory authority and without the need for new legislation.

The federal government is a distributed beast that does not turn on a dime. Agencies’ compliance with the EO remains to be seen. The timelines for implementation of the EO’s various provisions (generally 6-12 months) are simultaneously slow compared to the pace of change in AI, and rapid compared to the typical pace of policy making. In many cases it’s not clear if agencies have the funding and expertise to do what’s being asked of them. There is a real danger that it turns into a giant mess.

As a point of comparison, a 2020 EO required federal agencies to publish inventories of how they use AI — a far easier task compared to the present EO. Three years later, compliance is highly uneven and inadequate.

In short, the Biden-Harris EO is bold in its breadth and ambition, but it is a bit of an experiment, and we just have to wait and see what its effects will be.

Endnotes

We looked at the provisions for regulating AI discussed in each of the following papers and policy proposals, and clustered them into the six broad categories we discuss above:

Further reading

The EU AI Act, the UK Frontier AI Taskforce, the UK Competition and Markets Authority foundation model market monitoring initiative, US SAFE Innovation Framework, NIST Generative AI working group, the White House voluntary commitments, FTC investigation of OpenAI, the Chinese Generative AI Services regulation, and the G7 Hiroshima AI Process all have implications for open foundation models.

2

Liability for harms from products that incorporate AI would be much more justifiable than for the underlying models themselves. Of course, in many cases the two developers might be the same.

3

The EO requires the Secretary of Commerce to “determine the set of technical conditions for a large AI model to have potential capabilities that could be used in malicious cyber-enabled activity, and revise that determination as necessary and appropriate.” The compute threshold is a stand-in until such a determination is made. There are various other details that we have omitted here.

4

It might even lead to innovation in more computationally efficient training methods, although it is hard to imagine that the reporting requirement provides more of an incentive for this than the massive cost savings that can be achieved through efficiency improvements.

5

For the sake of completeness: regulatory carve outs for open or non-commercial models are another possible way in which policy can promote openness, which this EO does not include.

Transparency and auditing

There is a glaring absence of transparency requirements in the EO — whether pre-training data, fine-tuning data, labor involved in annotation, model evaluation, usage, or downstream impacts. It only mentions red-teaming, which is a subset of model evaluation.

This is in contrast to another policy initiative also released yesterday, the G7 voluntary code of conduct for organizations developing advanced AI systems. That document has some emphasis on transparency.

Antitrust enforcement

The EO tasks federal agencies, in particular the Federal Trade Commission, with promoting competition in AI. The risks it lists include concentrated control of key inputs, unlawful collusion, and dominant firms disadvantaging competitors.

What specific aspects of the foundation model landscape might trigger these concerns remains to be seen. But it might include exclusive partnerships between AI companies and big tech companies; using AI functionality to reinforce walled gardens; and preventing competitors from using the output of a model to train their own. And if any AI developer starts to acquire a monopoly, that will trigger further concerns.

All this is good news for openness in the broader sense of diversifying the AI ecosystem and lowering barriers to entry.

Incentives for AI development

The EO asks the National Science Foundation to launch a pilot of the National AI Research Resource (NAIRR). The idea began as Stanford’s National Research Cloud proposal and has had a long journey to get to this point. NAIRR will foster openness by mitigating the resource gap between industry and academia in AI research.

Various other parts of the EO will have the effect of increasing funding for AI research and expanding the pool of AI researchers through immigration reform.5 (A downside of prioritizing AI-related research funding and immigration is increasing the existing imbalance among different academic disciplines. Another side effect is hastening the rebranding of everything as AI in order to qualify for special treatment, making the term AI even more meaningless.)

While we welcome the NAIRR and related parts of the EO, we should be clear that it falls far short of a full-throated commitment to keeping AI open. The North star would be a CERN style, well-funded effort to collaboratively develop open (and open-source) foundation models that can hold their own against the leading commercial models. Funding for such an initiative is probably a long shot today, but is perhaps worth striving towards.

What comes next?

We have described only a subset of the provisions in the EO, focusing on those that might impact openness in AI development. But it has a long list of focus areas including privacy and discrimination. This kind of whole-of-government effort is unprecedented in tech policy. It is a reminder of how much can be accomplished, in theory, with existing regulatory authority and without the need for new legislation.

The federal government is a distributed beast that does not turn on a dime. Agencies’ compliance with the EO remains to be seen. The timelines for implementation of the EO’s various provisions (generally 6-12 months) are simultaneously slow compared to the pace of change in AI, and rapid compared to the typical pace of policy making. In many cases it’s not clear if agencies have the funding and expertise to do what’s being asked of them. There is a real danger that it turns into a giant mess.

As a point of comparison, a 2020 EO required federal agencies to publish inventories of how they use AI — a far easier task compared to the present EO. Three years later, compliance is highly uneven and inadequate.

In short, the Biden-Harris EO is bold in its breadth and ambition, but it is a bit of an experiment, and we just have to wait and see what its effects will be.

Endnotes

We looked at the provisions for regulating AI discussed in each of the following papers and policy proposals, and clustered them into the six broad categories we discuss above:

- Senators Blumenthal and Hawley's Bipartisan Framework for U.S. AI Act calls for licenses and liability as well as registration requirements for AI models.

- A recent paper on the risks of open AI models by the Center for the Governance of AI advocates for licenses, liability, audits, and in some cases, asks developers not to release models at all.

- A coalition of actors in the open-source AI ecosystem (Github, HF, EleutherAI, Creative Commons, LAION, and Open Future) put out a position paper responding to a draft version of the EU AI Act. The paper advocates for carve outs for open-source AI that exempt non-commercial and research applications of AI from liability, and it advocates for obligations (and liability) to fall on the downstream users of AI models.

- In June 2023, the FTC shared its view on how it investigates antitrust and anti-competitive behaviors in the generative AI industry.

- Transparency and auditing have been two of the main vectors for mitigating AI risks in the last few years.

- Finally, we have previously advocated for defending the attack surface to mitigate risks from AI.

Further reading

- For a deeper look at the arguments in favor of registration and reporting requirements, see this paper or this short essay.

- Widder, Whittaker, and West argue that openness alone is not enough to challenge the concentration of power in the AI industry.

The EU AI Act, the UK Frontier AI Taskforce, the UK Competition and Markets Authority foundation model market monitoring initiative, US SAFE Innovation Framework, NIST Generative AI working group, the White House voluntary commitments, FTC investigation of OpenAI, the Chinese Generative AI Services regulation, and the G7 Hiroshima AI Process all have implications for open foundation models.

2

Liability for harms from products that incorporate AI would be much more justifiable than for the underlying models themselves. Of course, in many cases the two developers might be the same.

3

The EO requires the Secretary of Commerce to “determine the set of technical conditions for a large AI model to have potential capabilities that could be used in malicious cyber-enabled activity, and revise that determination as necessary and appropriate.” The compute threshold is a stand-in until such a determination is made. There are various other details that we have omitted here.

4

It might even lead to innovation in more computationally efficient training methods, although it is hard to imagine that the reporting requirement provides more of an incentive for this than the massive cost savings that can be achieved through efficiency improvements.

5

For the sake of completeness: regulatory carve outs for open or non-commercial models are another possible way in which policy can promote openness, which this EO does not include.

Dare Obasanjo (@carnage4life@mas.to)

This is a thoughtful analysis of the Biden executive order on AI. Key positives is that it avoided the more restrictive approaches advocated by big tech AI doomers such as restricting the ability to create large models to licensed (aka big tech) companies. Instead it focuses on specific areas...

When comparing two models, a common reference point of compute is often used.

If you trained a 7b model with 3x the number of tokens/compute to beat a 13b model, did you really beat it? Probably not.

Here's a paper we wrote in 2021 (arxiv.org/abs/2110.12894) that I still found to be super relevant in 2023. @m__dehghani @giffmana

There's a lot of misnomers around efficiency and here's why it's super important to reason properly about this.

Some points:

1. Model comparisons can be tricky w.r.t to compute/efficiency. (e.g., FLOPs, throughput, parameters) can easily change the relative comparisons.

2. NLPers like to use number of parameters as an all encompassing absolute metric. There is a strong bias that size of the model is more important than anything else. Often times, the training FLOPs behind the model is not considered. Models are referred to as Model X 4B or Model Y 10B and not Model Z 6E22 flops.

3. There are people that think that if you train for longer, it's a win. Sure, from an inference point of view, yes, maybe. But it doesn't necessarily mean the modeling behind or recipe is better. I've seen this being conflated so many times.

4. Sparsity of models is sometimes overlooked and very tricky to compare apples to apples. Models can have different FLOP-parameter ratio (encoder-decoder vs decoder, sparse vs dense, universal transformer etc). Many people actually don't know this about encoder-decoders.

5. In the past, I've seen works that claim huge efficiency gains by using "adapters" because there are far fewer "trainable parameters". It sounds impressive on paper and fools the unsuspecting reviewer since it obfuscates the fact that inference/training speed does not benefit from the same boost.

6. Methods can sometimes claim superior theoretical complexity but can be 10x slower in practice because of implementation details or hardware constraints. (many efficient attention methods did not take off because of this).

When writing this paper "the efficiency misnomer" , I think we all felt that a holistic view of compute metrics need to be taken into account.

, I think we all felt that a holistic view of compute metrics need to be taken into account.

TL;DR: parameter-matching < flop/throughput matching but taking into account everything holistically is important.

If you care about one thing, sure, optimise for that. But if you're making general model comparisons, this can make things confusing real fast.

It's a 2 year old paper, but still important especially so in this new age of LLM noise.

If you trained a 7b model with 3x the number of tokens/compute to beat a 13b model, did you really beat it? Probably not.

Here's a paper we wrote in 2021 (arxiv.org/abs/2110.12894) that I still found to be super relevant in 2023. @m__dehghani @giffmana

There's a lot of misnomers around efficiency and here's why it's super important to reason properly about this.

Some points:

1. Model comparisons can be tricky w.r.t to compute/efficiency. (e.g., FLOPs, throughput, parameters) can easily change the relative comparisons.

2. NLPers like to use number of parameters as an all encompassing absolute metric. There is a strong bias that size of the model is more important than anything else. Often times, the training FLOPs behind the model is not considered. Models are referred to as Model X 4B or Model Y 10B and not Model Z 6E22 flops.

3. There are people that think that if you train for longer, it's a win. Sure, from an inference point of view, yes, maybe. But it doesn't necessarily mean the modeling behind or recipe is better. I've seen this being conflated so many times.

4. Sparsity of models is sometimes overlooked and very tricky to compare apples to apples. Models can have different FLOP-parameter ratio (encoder-decoder vs decoder, sparse vs dense, universal transformer etc). Many people actually don't know this about encoder-decoders.

5. In the past, I've seen works that claim huge efficiency gains by using "adapters" because there are far fewer "trainable parameters". It sounds impressive on paper and fools the unsuspecting reviewer since it obfuscates the fact that inference/training speed does not benefit from the same boost.

6. Methods can sometimes claim superior theoretical complexity but can be 10x slower in practice because of implementation details or hardware constraints. (many efficient attention methods did not take off because of this).

When writing this paper "the efficiency misnomer"

TL;DR: parameter-matching < flop/throughput matching but taking into account everything holistically is important.

If you care about one thing, sure, optimise for that. But if you're making general model comparisons, this can make things confusing real fast.

It's a 2 year old paper, but still important especially so in this new age of LLM noise.

Nvidia Is Piloting a Generative AI for its Engineers

ChipNeMo summarizes bug reports, gives advice, and writes design-tool scripts

spectrum.ieee.org

spectrum.ieee.org

SEMICONDUCTORSNEWS

Nvidia Is Piloting a Generative AI for Its Engineers

ChipNeMo summarizes bug reports, gives advice, and writes design-tool scripts

SAMUEL K. MOORE31 OCT 2023

3 MIN READ

NICHOLAS LITTLE

EDACHIP DESIGNNVIDIALLMSDEBUGGINGELECTRONIC DESIGN AUTOMATION

In a keynote address at the IEEE/ACM International Conference on Computer-Aided Design Monday, Nvidia chief technology officer Bill Dally revealed that the company has been testing a large-language-model AI to boost the productivity of its chip designers.

“Even if we made them 5 percent more productive, that’s a huge win,” Dally said in an interview ahead of the conference. Nvidia can’t claim it’s reached that goal yet. The system, called ChipNeMo, isn’t ready for the kind of large—and lengthy—trial that would really prove its worth. But a cadre of volunteers at Nvidia is using it, and there are some positive indications, Dally said.

ChipNeMo is a specially tuned spin on a large language model. It starts as an LLM made up of 43 billion parameters that acquires its skills from one trillion tokens—fundamental language units—of data. “That’s like giving it a liberal arts education,” said Dally. “But if you want to send it to graduate school and have it become specialized, you fine-tune it on a particular corpus of data…in this case, chip design.”

That took two more steps. First, that already-trained model was trained again on 24 billion tokens of specialized data. Twelve billion of those tokens came from design documents, bug reports, and other English-language internal data accumulated over Nvidia’s 30 years work designing chips. The other 12 billion tokens came from code, such as the hardware description language Verilog and scripts for carrying things out with industrial electronic design automation (EDA) tools. Finally, the resulting model was submitted to “supervised fine-tuning,” training on 130,000 sample conversations and designs.

The result, ChipNeMo, was set three different tasks: as a chatbot, as an EDA-tool script writer, and as a summarizer of bug reports.

Acting as a chatbot for engineers could save designers time, said Dally. “Senior designers spend a lot of time answering questions for junior designers,” he said. As a chatbot, the AI can save senior designer’s time by answering questions that require experience, like what a strange signal might mean or how a specific test should be run.

Chatbots, however, are notorious for their willingness to lie when they don’t know the answer and their tendency to hallucinate. So Nvidia developers integrated a function called retrieval-augmented generation into ChipNeMo to keep it on the level. That function forces the AI to retrieve documents from Nvidia’s internal data to back up its suggestions.

The addition of retrieval-augmented generation “improves the accuracy quite a bit,” said Dally. “More importantly, it reduces hallucination.”

In its second application, ChipNeMo helped engineers run tests on designs and parts of them. “We use many design tools,” said Dally. “These tools are pretty complicated and typically involve many lines of scripting.” ChipNeMo simplifies the designer’s job by providing a “very natural human interface to what otherwise would be some very arcane commands.”

ChipNeMo’s final use case, analyzing and summarizing bug reports, “is probably the one where we see the prospects for the most productivity gain earliest,” said Dally. When a test fails, he explained, it gets logged into Nvidia’s internal bug-report system, and each report can include pages and pages of detailed data. Then an “ARB” (short for “action required by”) is sent to a designer for a fix, and the clock starts ticking.

ChipNeMo summarizes the bug report’s many pages into as little as a single paragraph, speeding decisions. It even can write that summary in two modes: one for the engineer and one for the manager.

Makers of chip-design tools, such as Synopsys and Cadence, have been diving into integration of AI into their systems. But according to Dally, they won’t be able to achieve the same thing Nvidia is after.

“The thing that enables us to do this is 30 years of design documents and code in a database,” he said. ChipNeMo is learning “from the entire experience of Nvidia.” EDA companies just don’t have that kind of data.

FROM YOUR SITE ARTICLES

I can't wait until it's possible for me to generate content like this based on fan fiction using consumer hardware.