Field Marshall Bradley

Veteran

You're confusing culture with social norms.

Nope.. I am not...

You're confusing culture with social norms.

I don’t think it’s a matter of not being able to define the culture for most AA’s. A lot of people don’t take AA cultural traits seriously to begin with because of bias and preconceived notions. So even when we provide clear concise examples, they get shot down because of some dumb standard that these same people don’t apply to other cultures so it’s like what’s the point?Here is the thing... the fact that most AAs can’t tell you what our culture is, or what it stands for, is indicative that something is broken or missing in regards to what is supposed to be our culture....

Not to mention the fact that when people ask or question AA culture they’re never clear on what they think defines culture in general. So it just comes off like trolling...which 90% of the time I think that’s all it really is.

Do other cultures get put under a microscope like ours to this degree? This shyt has always been a weird conversation to me.

I don’t think it’s a matter of not being able to define the culture for most AA’s. A lot of people don’t take AA cultural traits seriously to begin with because of bias and preconceived notions. So even when we provide clear concise examples, they get shot down because of some dumb standard that these same people don’t apply to other cultures so it’s like what’s the point?

Not to mention the fact that when people ask or question AA culture they’re never clear on what they think defines culture in general. So it just comes off like trolling...which 90% of the time I think that’s all it really is.

Do other cultures get put under a microscope like ours to this degree? This shyt has always been a weird conversation to me.

Culture - the products, art, and culminations of a group of people who share the same identity.

Social norms/social clocks - expectations of behaviors for individuals in a specific society.

People who think less of AAs will define culture as social norms then point to the dysfunction in our communities as a sign of "no culture."

A homegoing (or home-going) service is an African-American Christian funeral tradition marking the going home of the deceased to the Lord or to heaven. It is a celebration that has become a vibrant part of African American history and culture. As with other traditions, practices, customs and norms of African American culture, this ritual for dealing with death was shaped by the African American experience.

A homegoing service follows many of the same practices as a funeral service. There are pall bearers and flowers and the service is typically held in a Christian church. But, because African-American Christians believe death marks the return to the lord and an end to the pain and suffering of mortal life, the homegoing service is an occasion marked by rejoicing because the deceased is going on to a better place.

A homegoing service usually contains some or all of these elements:

A homegoing service is sometimes reminiscent of an African-American Christian church service. In addition to the eulogy, there is often a sermon and a choir that sings gospel hymns. The service often allows for friends and family to speak briefly about their remembrances of the deceased. Homegoing Service goers may experience both mourning and rejoicing.

- Musical prelude

- Processional

- Prayers

- Songs (Hymns of Comfort)

- Funeral Readings (Scripture, Poem, Prayer, Old Testament, and New Testament) Acknowledgements

- Reading of Cards & Condolences

- Reading of Funeral Resolutions

- Obituary Reading

- Eulogy or Tribute

- Final Viewing

- Benediction

- Recessional, and Interment or Committal

Although many variations exist in African American funeral traditions, most variations share some attributes. Because of the history of African Americans in the United States, many of these variations represent an amalgamation of cultures. For many African Americans, funerals are not only a time to say goodbye and send the deceased safely off on a spiritual journey, but it also provides an opportunity to bind the family closer.

The Wake

After a person dies, it takes five to seven days before the funeral. However, since it is important to have the immediate family present, this time can be extended if any conflict exists with the proposed date. The day before the funeral, a wake or viewing of the body is held. In earlier times, the wake would take place in the family’s home, however, most wakes are now held at the funeral parlor. The wake represents a time for family and friends to gather and say goodbye to the deceased. It is also a time to pay respect to the family. Food can be served at the home or church after a wake.

Funeral Day

Before the family enters the church, friends and other attendees at the funeral get a last chance to view the body. The immediate family and other relatives walk down the aisle toward the casket. Designated seating on the left side of the church is usually designated for the family. The funeral begins with the reading of the Bible followed by an opening song by the choir or a family member. The obituary is read prior to the eulogy, which is generally performed by a pastor.

Flower Girls

In addition to the pallbearers who carry the casket, African American funerals have flower girls who are responsible for carrying the flowers placed on or around the casket. Flowers girls are usually the nieces, cousins or close friends of the deceased. They usually sit together in the first few rows opposite the family. At the end of the eulogy and after the last prayer, they are signaled to come retrieve the flowers, which are placed by the grave or loaded into the hearse.

Funeral Procession

The funeral procession, also called the last ride among some southern African Americans, is the idea of spiritually “going home” for the deceased. The immediate family rides directly behind the hearse to the cemetery, followed by the other funeral attendees. The funeral procession rides with the headlights or emergency blinkers on and some African Americans place purple flags on the antenna. An important tradition that occurs at the cemetery site is ensuring that the body is buried with the feet facing east so the spirit can rise on Judgment Day.

Death transcends race, religion and culture, but the customs associated with it are often unique to specific cultures -- for instance, African American Southern Baptists. Because most African American funeral customs borrow from other practices such as traditional African funeral practices and Christianity, African American mourners, particularly Southern Baptists, view death as a time to both celebrate and mourn.

Home-going Service

According to the Encyclopedia of Death and Dying, many African religions teach that life is eternal and death is the beginning of eternal life in a spiritual realm. Because African American culture adopted this belief, along with Christian beliefs, many refer to funerals as home-going celebrations. Mourners believe the deceased has transitioned from living on earth to living with the Heavenly Father and his son, Jesus Christ.

Order of Service

African American Southern Baptists typically hold funerals at churches. During the service, mourners both grieve the death of a loved one and celebrate her life and the legacy she leaves. The service usually opens with a family processional. Choirs sing gospel songs, while friends and family are encouraged to provide short speeches or poems dedicated to the deceased person. An ordained minister provides the official eulogy. During an African American Southern Baptist eulogy, the minister provides details about the deceased person’s relationship with God and reminds mourners that the deceased now lives eternally with God.

Keening

Although home-going services celebrate the deceased person’s transition from earth to heaven, death’s finality is palpable. Keening, the act of lamenting vocally, according to Funeralwise.com, is “The most distinguishing characteristic in African American funeral services.” During an African American Southern Baptist funeral, it is common for friends and relatives of the deceased to shout, wail and in some cases, faint. To an outsider this may be a dramatic expression of grief; however, it often occurs after the final viewing of the body and after deceased person’s coffin has closed, which literally means that it is the last time loved ones will see the departed’s body. This poignant expression of grief continues until the end of the service when pallbearers carry the deceased person’s coffin to the hearse, and mourners follow the hearse to the gravesite for burial.

Repast

After most African American funerals, friends and family gather at the home of the bereaved or remain at the church for the repast, a meal traditionally served after a funeral. Wealthier families sometimes hire caterers to prepare and serve the meal. In most cases, however, friends and family members of the deceased prepare potluck dishes. Although grief and mourning linger, the repast is a family reunion, a time to reconnect with loved ones that time and location have separated. During this gathering, mourners suspend their despair and socialize with family and friends.

The majority of African-Americans have the same funeral traditions that all other ethnic groups living in America hold. But with any group, there can be two factors that introduce some differences in traditions: religion and cultural background. Some African-American communities, but not all, reach into their past to borrow traditions stemming from a number of cultures. For example, in an article about death, "The African-American Funeral Director," PBS reports that because African-Americans had no opportunity to honor their dead during slavery, they began holding grand, celebratory funerals after the Civil War ended, a tradition that persists today.

Homegoings

During slavery, most black people in America viewed death as a blessed pardon from a harsh and brutal life of forced labor. It was commonly agreed that dying meant an African slave's soul would return home to ancestral Africa in a “homegoing.” In the 21st century, many African-American communities still embrace the concept of a homegoing, but instead they believe the departing soul goes to heaven versus the mother country from which their ancestors were brought. Today a homegoing is meant to be a happy occasion because the departed is going home to be at peace and to meet his ancestors who are waiting for him on the other side -- a concept celebrated at funeral services and during wakes.

Flower Girls

Flower girls are the female counterpart of the male pallbearer and perform a number of responsibilities that include offering individualized attention to grieving family members. Flower girls are more common in Southern African-American funeral rituals, and being asked to be a flower girl was a huge honor granted to granddaughters, nieces and friends of the family. About 40 years ago, these girls who arranged flowers at the front of the sanctuary and around the coffin were as young as 7, but in the 1970s a shift took place that saw older girls and women take on the role to mark "the passing over Jordan."

The Jazz Funeral

One of the most celebrated African-American funeral traditions stems from New Orleans and involves an elaborate funeral procession of jazz music. During slavery, the desire to provide a proper burial for loved ones was strong, but restrictive. As time passed and brass bands became popular in the early18th century, they would serenade the corpse pulled by a horse-drawn cart on the way to the cemetery with ensembles of thoughtful and lively band music that, over time, took on a jazz flavor. The jazz funeral also enveloped concepts rooted in African ideology that became standard practices, such as placing people behind and alongside the horse-drawn casket with loud noisemakers to confuse the spirits and lead them astray from trying to misguide the deceased person's soul.

Potlucks

Most African-American families are closely-knit and come together in times of need, including funerals. But just as funerals in some African-American cultures are a time of sorrow, they are also a time for celebrating the deceased person's life with storytelling and congregating together in celebration. Preparing food for mourning families is a time-honored tradition in which each person or household prepares a dish and brings it for all to enjoy. For years funeral potlucks were typically held in the deceased person's home but now most of them take place in church overflow and community rooms and strive to put the "fun" in "funeral."

On April 7, 2017, my family and I hosted a home-going to celebrate the life of my great aunt. A home-going is a traditional African American, Christian funeral service held to rejoice the deceased person’s returning to heaven, and this elaborate funeral ritual has a deep history dating back to the arrival of African slaves in America in the 1600s. There are several aspects that set this service apart from the traditional funeral, including the week-long visitation to the bereaved family’s home, the wake, and the elaborate funeral procession. About a week prior to the service, a plethora of friends, neighbors, co-workers, and family members who live in different areas of the world travel to visit the bereaved family every day to offer their condolences (the same people may or may not visit the family every day). A wake is then held for the deceased between 2 to 3 days prior to the funeral, and this allows family members and friends to have few personal moments with the deceased. On the day of the funeral, a group of police escorts arrive to the bereaved family’s house, and the family is escorted to the church. During this process, the family bypasses certain traffic laws, such as passing through red lights. At the church, some of the women of the family act as flower girls, and their job is to remove the elaborate bouquets of flowers that will be placed on the casket during the funeral. The service itself is often an emotional, high energy event that entails family members singing African American hymns and a boisterous eulogy by the pastor. Afterwards, the funeral procession travels to the gravesite, and people wait until the body is partially buried before leaving to return to the church or to the family’s house to dine with one another.

I never realized that my burial practice was significant or distinct to Black American people until taking this class, which is unnerving to me because home-going services are integral to my family’s traditions. They allow us to celebrate the life of our loved one while showering them with expensive items, such as custom caskets, support a black business (an African American mortuary), and re-connect with family. These services also allow me to learn about the richness and history of my family and our culture through our conversations as well as through visiting the gravesite because generations of my family are buried in a black owned gravesite in Atlanta.

The Jazz Funeral

One of the most celebrated African-American funeral traditions stems from New Orleans and involves an elaborate funeral procession of jazz music. During slavery, the desire to provide a proper burial for loved ones was strong, but restrictive. As time passed and brass bands became popular in the early18th century, they would serenade the corpse pulled by a horse-drawn cart on the way to the cemetery with ensembles of thoughtful and lively band music that, over time, took on a jazz flavor. The jazz funeral also enveloped concepts rooted in African ideology that became standard practices, such as placing people behind and alongside the horse-drawn casket with loud noisemakers to confuse the spirits and lead them astray from trying to misguide the deceased person's soul.

Jazz funeral is a common name for a funeral tradition with music which developed in New Orleans, Louisiana.

The term "jazz funeral" was long in use by observers from elsewhere, but was generally disdained as inappropriate by most New Orleans musicians and practitioners of the tradition. The preferred description was "funeral with music"; while jazz was part of the music played, it was not the primary focus of the ceremony. This reluctance to use the term faded significantly in the final 15 years or so of the 20th century among the younger generation of New Orleans brass band musicians more familiar with the post-Dirty Dozen Brass Band and Soul Rebels Brass Band funk influenced style than the older traditional New Orleans jazz.

The tradition blends strong European and African cultural influences. Louisiana's colonial past gave it a tradition of military style brass bands which were called on for many occasions, including playing funeral processions.This was combined with African spiritual practices, specifically the Yoruba tribe of Nigeria and other parts of West Africa. Jazz funerals are also heavily influenced by early twentieth century African American Protestant and Catholic churches and black brass bands idea of celebrating after death in order to please the spirits who protect the dead. Another group that has had an impact on jazz funerals is the Mardi Gras Indians.

The tradition was widespread among New Orleanians across ethnic boundaries at the start of the 20th century. As the common brass band music became wilder in the years before World War I, some white New Orleanians considered the hot music disrespectful, and such musical funerals became rare among the city's white citizens. After the 1960s, it gradually started being practised across ethnic and religious boundaries. Most commonly such musical funerals are done for individuals who are musicians themselves, connected to the music industry, or members of various social aid and pleasure clubs or Carnival krewes who make a point of arranging for such funerals for members. Although the majority of jazz funerals are for African American musicians there has been a new trend in which jazz funerals are given to young people who have died.

The organizers of the funeral arrange for hiring the band as part of the services. When a respected fellow musician or prominent member of the community dies, some additional musicians may also play in the procession as a sign of their esteem for the deceased.

A typical jazz funeral begins with a march by the family, friends, and a brass band from the home, funeral home or church to the cemetery. Throughout the march, the band plays somber dirges and hymns. A change in the tenor of the ceremony takes place, after either the deceased is entombed, or the hearse leaves the procession and members of the procession say their final goodbye and they "cut the body loose". After this the music becomes more upbeat, often starting with a hymn or spiritual number played in a swinging fashion, then going into popular hot tunes. There is raucous music and cathartic dancing where onlookers join in to celebrate the life of the deceased. Those who follow the band just to enjoy the music are called the second line, and their style of dancing, in which they walk and sometimes twirl a parasol or handkerchief in the air, is called second lining.

Some typical pieces often played at jazz funerals are the slow, and sober song "Nearer My God to Thee" and such spirituals as "Just a Closer Walk With Thee". The later more upbeat tunes frequently include "When the Saints Go Marching In" and "Didn't He Ramble".

Turn of the century New Orleans-style jazz had deep roots in Spirituals and Gospel Hymns. Jazz musicians continue to look to church music for inspiration, taking familiar themes and melodies from hymns and swinging them in a jazz band style. The Jim Cullum Jazz Band is no exception. They regularly present their program of hymns and spirituals—such as “Deep River” and "When the Roll Is Called Up Yonder"—in churches of all denominations.

Special guest and Louisiana native Topsy Chapman is very familiar with traditional African-American gospel repertoire. Topsy leads a vocal trio called Solid Harmony with her two daughters, and her father, Norwood Chapman born in 1898, was a vocal music instructor steeped in the gospel tradition. Growing up in her large family, everyone sang hymns in a vocal style particular to his or her own generation. Here, Topsy demonstrates differences between the gospel singing styles of her father's generation and that of her own 1960s contemporaries, like Aretha Franklin.

Explaining the unique place Spirituals hold in the American musical experience, Harry "Sweets" Edison, the great Count Basie trumpeter, had this to say on another Riverwalk Jazz production:

“…Spirituals are one of the oldest forms of art and culture we have in America, jazz and the blues came out of spirituals. Spirituals came out of the days of slavery. My great-grandmother, the one who lived to be 108, she used to tell me about it because she was born in slavery times. You know, they worked from sunup to sundown. Sometimes they worked all night. They worked so hard; they just waited to die, because they would be out of their misery. They sang the Spirituals because the music gave them hope. The music gave them strength to endure the day. They sang for relief.”

On this Riverwalk Jazz production, Topsy Chapman joins The Jim Cullum Jazz Band to perform a variety of Spirituals and Gospel Hymns:

"Go Down Moses" is a traditional American Negro Spiritual sung by the Fisk Jubilee Singers in the 1870s. The lyric uses an Old Testament narrative from the book of Exodus in which God exhorts Moses to stand up to the Egyptian Pharaoh, who had enslaved the Israelites, and make the demand, “ Let my people go.” This Spiritual entered popular culture through a recording by the bass baritone Paul Robeson and has also been recorded by jazz artists Fats Waller and Louis Armstrong. It became an anthem of the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s.

The Fisk Jubilee Singers. Photo in public domain.

"His Eye Is On the Sparrow," a staple of African American church services, is a gospel hymn first copyrighted in 1905 by two white songwriters Charles H. Gabriel, the composer and the lyricist Civilla D. Martin. The lyric is inspired by words from the Gospel of St. Matthew, “Look at the birds of the air, they toil not …and yet our heavenly Father feeds them.” The song title “His Eye Is On The Sparrow” is often associated with early jazz and blues singer Ethel Waters, who used it to name her autobiography.

Composed in 1912 by C. Austin Miles (1868-1946), a pharmacist turned hymn writer and church music director, the gospel hymn "In the Garden" became the theme song of the Billy Sunday evangelistic crusades. Artists as diverse as Roy Rogers and Perry Como have recorded popular versions of this hymn.

Born the son of a Baptist preacher in 1899, Thomas A. Dorsey began his musical career writing tunes for King Oliver and his Creole Jazz Band. Dorsey made a living playing piano for hard-core blues shouters like Bessie Smith and Gertrude "Ma" Rainey. When his wife died in childbirth and he lost his child a few days later, he wrote his first gospel hymn, "Precious Lord Take My Hand." Dorsey went on to become one of the most respected and prolific hymn writers of the 20th century. Here, The Jim Cullum Jazz Band performs it as an instrumental.

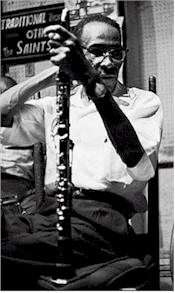

George Lewis. © 1997 John Spragens, Jr. courtesy of All That....

There's nowhere that Jazz and Gospel music come together with a more beautiful result than in traditional New Orleans funerals. For more than 100 years, brass bands like the Eagle and the Onward Bands have marched through the streets of New Orleans playing their unique combination of sacred music and hot jazz for funeral processions. New Orleans-based clarinetist Evan Christopher joins The Jim Cullum Jazz Band to re-create the atmosphere with an original arrangement of the dirge "Flee As a Bird," followed by the joyous "Over in the Gloryland."

"Just a Closer Walk with Thee,” another dirge played at New Orleans jazz funerals, gained national popularity with the re-discovery of trumpeter Bunk Johnson, who spearheaded the traditional New Orleans jazz revival of the 1940s. A 1945 recording by Bunk Johnson with George Lewis on clarinet led to a cult-like following for the pair of elderly musicians.

Our show this week concludes with a rousing group-sing led by Topsy Chapman on "Down by the Riverside." The gospel song was first published in Plantation Melodies: A Collection of Modern, Popular and Old-time Negro-Songs of the Southland in 1918, and first recorded by the Fisk Jubilee Singers. It’s chorus “Ain’t gonna study war no more…”has made it an enduring hymn of civil rights marches.

The roots of the jazz funeral date back to 17th Century Africa, where the Dahomeans of Benin and Yoruba of Nigeria, West Africa, laid its foundation. Secret societies of the Dahomeans and Yoruba people assured fellow tribesmen they would receive a proper burial when their time came. To honor this guarantee, resources were pooled in what many consider an early form of life insurance.

This concept remained strong with Africans brought to America as slaves, and as time passed it became a basic principle of the familiar social and pleasure clubs, guaranteeing proper burial to any member who passed. As brass bands gained in popularity in New Orleans, for everything from Mardi Gras to political rallies, they were likewise called on to play processional music for these funeral services.

Eileen Southern, Professor Emerita of Music and Afro-American Studies at Harvard University, in "The Music of Black Americans" wrote, “On the way to the cemetery it was customary to play very slowly and mournfully a dirge, or an ‘old Negro spiritual’ such as ‘Nearer My God to Thee,’ but on the return from the cemetery, the band would strike up a rousing, 'When the Saints Go Marching In,’ or a ragtime song such as 'Didn't He Ramble.'”

In a traditional jazz funeral, the band meets at the church or funeral parlor where the dismissal services are being conducted. After the service, the band leads a procession slowly through the neighborhood to the cemetery. At the conclusion of the interment ceremony, the band leads the procession from the gravesite without playing. Once reaching a respectful distance, the lead trumpet sounds a two-note preparatory riff to alert his fellow musicians. At this point the band sheds its solemnity in favor of lively, joyous music; and family, friends and other celebrants may join in spontaneously behind the band in what is known as the "second line," often brandishing umbrellas or canes while dancing in celebration.

Expression of the tradition outside of New Orleans varies. Often all music is played at the funeral home as part of the service, or at a hall or similar gathering place for a reception. More and more the music is played at a memorial service following cremation. It’s entirely up to the family.

Since the 1970s, brass bands like the Dirty Dozen, the Soul Rebels, Pin Stripe, Algiers, Rebirth, and many others have carried the torch of the jazz funeral. We aspire to make "Band of Praise" worthy of that list, offering an authentic brass band to embrace this tradition.

So dope lol some of the things we do, I had no idea why we did itHome-goings: A Black American Funeral Tradition

African-American Funeral Traditions

African-American Funeral Traditions | Synonym

Funeral Customs of African American Southern Baptists

Funeral Customs of African American Southern Baptists | Synonym

African American Funeral Traditions

African American Funeral Traditions | Synonym

Do other cultures get put under a microscope like ours to this degree? This shyt has always been a weird conversation to me.

Facts. That egg head ass nikka (prolly a foreign kneegrow) need not have something as simple as this go over his head.