Your ad agency was successful at the time. Did you have any apprehensions about leaving it behind?

I believed in Prince enough to walk out of my ad agency—doing millions of dollars worth of business—and just put my life into him. I really loved him as a human being. People say, "Well, wasn't he strange?" Well, yeah, we're all strange. I've never met an artist who wasn't strange. And so the fact that he was a little aloof and quiet—not around me, but around everybody else—never bothered me. I was happy he was that way. If he had been, “Hey, come on over, let's smoke a joint and have some fun,” I wouldn’t have managed him!

[Laughs.] So eventually we signed Prince to a contract, the demo tape was put together.

An interesting story about the demo tape: there's a song that's on the first album called "Baby" and he wanted an orchestra. The only orchestra I knew in town at that point was a radio station orchestra, so I brought them in. When I came down to the studio to see how things were going on, Prince was fit to be tied, and these guys were like 90 years old, all of them, and they couldn't quite get it.

[Laughs.] Prince worked with them and worked with them—I don't know how much he knew about writing music at that point, but he worked with them to the point where they rewrote and charted exactly the way he wanted it. Here's this 18-year-old kid working with these pretty cool players, orchestra guys, and he rewrote those parts and got 'em to do it.

So now you have the demos up to par, you pulled together a press kit, and then you started shopping him around?

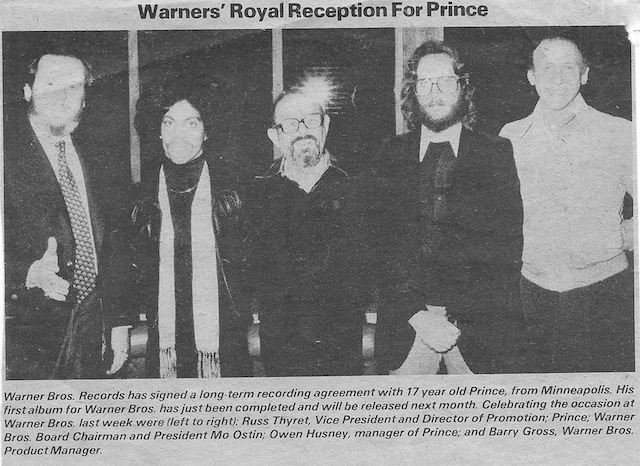

Yeah I called Warner Brothers—I’d done some work for them in my ad agency before—so I called back Russ Thyret [the label CEO] and said, “I'm gonna make up that favor to you, listen, Columbia Records is flying us out. Would you like to hear this young genius I have? Would you like to hear him while I'm out here on Columbia's dime?” And he was like, “Yeah, absolutely!” So now I had an appointment at Warner Brothers to play and then I called Columbia, and I said, “Hey, Warner Brothers is flying us out and while we're here on their dime, would you like to hear the demo of this young genius from Minneapolis?” Then I called A&M Records, and I said, “Listen, I'm out here making presentations to Columbia and to Warners, would you like to hear this?” But I always knew that I was gonna go to Warners. They were just the top artist-friendly label of that era. The other labels seemed cold. So I lied my way into appointments at all of the labels.

These days I teach [the business of music] at UCLA and I teach my students how to lie—as long as people don't get hurt. "Hey, I saw your girlfriend with another guy down there at that bar!" That's malicious lying. But when people don't get hurt and you can get somebody positioned—hey, have fun!

Savvy teachings. So you had three labels interested, but Warners was the one. The deal you ended up brokering was pretty lucrative I hear.

I knew that even though I wanted to go to Warner Brothers I needed to make this a very rich deal for Prince, because he needed a lot of support. I needed a bidding war. And then eventually I would go with Warner Brothers.

[Laughs.] I think that we're beyond the statute where they can sue me for saying this. The only label that we presented to that didn’t get it was RSO Records who had the Bee-Gees. I still have their rejection letter: “We think your artist is talented, but we don't think there's much of a future there, so we're passing.” I thought if I could get a bidding war together I could get a shytload of money and I could get three albums to develop Prince, which they won't do today. We got three albums firm and I'm 99 percent sure on this: it was the largest record deal for an unproven artist in history at that point.

How much did you sign for?

I think the whole deal was well over a million dollars. They wanted to take part of his publishing at the time, but I really didn't understand publishing. I just kept saying: I'm not prepared to have that discussion, because I didn't know what the hell it was and I wanted to run out of the meeting and get a book and read up on it. I knew if I said, “What is publishing?” they would have gotten another manager in there immediately. Finally they caved and the reason Prince owns all his publishing was because I didn't know what it was!

[Laughs.]

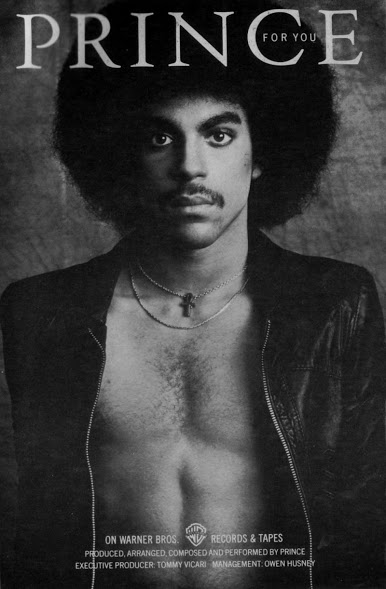

Notoriously Prince fought to produce his debut album despite his inexperience, but that was quite the battle.

They wanted Maurice White [founder of Earth, Wind & Fire] to produce and they threw out a couple of other names of people, maybe Norman Whitfield [The Temptations, Marvin Gaye]. I'll tell you what was really interesting about Prince—and he was not malicious about this at all—but he had already studied all of these artists, like Maurice and Norman and whoever else. He knew about them, and he didn’t want their imprint on his sound—he wanted to develop his own sound and I agreed with him. He even wrote me a little note that said, “Owen, I'm very respectful of these artists and these producers, but I can pick their music apart and I can tell it's not the imprint that I want to have on my sound.”

So now I gotta tell the chairman of Warner Brothers that no one is producing this unheard-of artist who's never made album: he's gonna produce himself. I went in and fought. They agreed to organize a test where they’d fly Prince out from Minneapolis and have him record all the instruments himself. But I told Prince, “Hey, you've got some free studio time, go make a song.” We flew out and Prince lays down a drum track just perfectly, comes back, lays down the bass guitar. Now there's a bunch of people standing around the studio, and he has no idea but they were the top producers of the era: Lenny Waronker, Russ Titelman, Eddie Templeman, plus a couple of Warner Brothers figures there. They were blown away. So the test worked.

I walked out into the hallway and they said, “Look, he obviously knows how to make a record, and it might cost us a throwaway album, but he'll get there.” There's not a label in this day and age that would do that. They wouldn't even take that kind of a chance. Prince probably wouldn't have succeeded now simply because of the constraints they’d have put on him. So we’d accomplished some greatness: the biggest record deal in history at that time for a new artist, we had that new artist be his own producer, and convinced the record label that he was gonna play all the instruments.

So the plan was to keep the whole production in Minneapolis and record with the engineer Tommy Vicari [Michael Jackson, Whitney, Justin Timberlake]. But then Vicari couldn’t do it in the studio for various reasons, and you didn’t want to make Prince go to LA. In the end you compromised and planned to lay down the record in Sausalito, across the bay from San Francisco, but that cogs didn’t exactly run smoothly in that situation either…

Right. About one week into the recording in Sausalito, Prince comes home and he says to me, “I can't work with the engineer.” I said, “Come on. I just got Warner Brothers to give us everything we wanted, and now I gotta get rid of their engineer?! They'll stop the project! It's all over!” He says, “Well, you gotta fire him. I'm gonna do it for you.”

Why didn't he like him?

He’s an incredible engineer, he's won Grammys, he's a top-notch guy. It doesn't mean he was bad, it just meant—he's not on my wavelength. Here's an interesting thing about Prince: he has the uncanny intellect and ability to absorb whatever’s going on in the room. It's very, very special and I think it's one of his great attributes. Two weeks in that studio with Tommy Vicari and he got it, “OK, I know how to do this.”

[Laughs]. So, then I had to tell Warner Brothers.

And did they freak out?

Oh, they were freaking out. At one time Warners got nervous, because I wasn't calling them and letting them know how things were going, that the President of Warner Brothers, and the VP of Promotion, Russ Thyret and Lenny Waronker flew up. They wanted to hear what was going on. Prince is recording the first song called "So Blue," on

For You, and there was no bass in it. Lenny says, “This could be great when you get a bass on there.” And Prince looks up and says, "There will be no bass. Get out. Get out of my studio." He just kicked the President and the VP of Promotion—the guy who's got to get his record played, you know.

[Laughs.] Just threw them out of the studio! And so I go out into the hallway, and my voice is cracking and they looked at me, and they said, "We get it. Let him go. Let him roll."

Wow. That's very understanding.

They were! That's why Warner Brothers had so many hits. If you look at Warner Brothers hits of the 70s, it's one after the next. So that was it, they never bothered us again. He spent a long, long, long time making that album, but he wanted it to be perfect, which, really, you don't want a perfect album, because perfect albums can be sterile; imperfections give it depth.

Let’s talk about some of the songs…

He did a song, an a capella song called "For You," it's like, 30 Prince voices overdubbed again and again and again, and it's just so cool and so right on and it’s the first song on the album. Most of his songs, "My Love Is Forever," "So Blue," "In Love," we had demoed before we got out there into the big time. Prince's focus, his brilliant creativity, I've seen it very rarely in this business where it's that complete. I actually think Michael Jackson's fairly unbelievably brilliant for what he was able to do and write and pull off and be in charge of what he’s done. Is Prince up there with John Lennon and Bob Dylan? Maybe, maybe not. If he's not, he's very close up in that realm. It’s a long-lasting career that has matured and he’s taken his audience on his trip, a journey over the years, and they've matured with you.

Do you have any stories about recording specific songs?

There's another song called "Baby" on the album that we also did as a demo. That's the one where I brought the orchestra in. Picture this: this kid just turned 18, he wrote the song about getting your girlfriend pregnant and now what are we gonna do? And the dilemma that you're faced with, and then, finally, at the end of the song, he says, “I hope our baby has eyes just like yours.” It's just so tender, and you know, Prince is a badass funk master, but there's a tenderness about a lot of stuff that he writes. If you listen to the lyrics, you get chills. "So Blue" is the same kind of thing. I think during that time, he got turned on to Joni Mitchell, and I think that's his homage to Joni.

Prince is like "Buy my album, I'm never doing this shyt again for a loooooooong time"

Prince is like "Buy my album, I'm never doing this shyt again for a loooooooong time"

Prince is like "Buy my album, I'm never doing this shyt again for a loooooooong time"

Prince is like "Buy my album, I'm never doing this shyt again for a loooooooong time"

Better safe than sorry.

Better safe than sorry.