IllmaticDelta

Veteran

What yall know about the African influence and reinterpretation of Christianity by the slaves in America?

http://nationalhumanitiescenter.org/tserve/nineteen/nkeyinfo/aareligion.htm

what yall know about the African based frenzy dance known as the "Ring Shout" basically being the origin of "getting the holy ghost" action

Hear that Dembow/reggaeton beat they're beating/stomping out

African American Christianity, Pt. I:

To the Civil War

The story of African-American religion is a tale of variety and creative fusion. Enslaved Africans transported to the New World beginning in the fifteenth century brought with them a wide range of local religious beliefs and practices. This diversity reflected the many cultures and linguistic groups from which they had come. The majority came from the West Coast of Africa, but even within this area religious traditions varied greatly. Islam had also exerted a powerful presence in Africa for several centuries before the start of the slave trade: an estimated twenty percent of enslaved people were practicing Muslims, and some retained elements of their practices and beliefs well into the nineteenth century. Catholicism had even established a presence in areas of Africa by the sixteenth century.

UVA Lib.

enlarge

Funeral in Guinea, west Africa, drawn by a French painter, ca. 1789 (detail)

UVA Lib.

enlarge

"Heathen practices in funerals," drawn by a Baptist missionary in Jamaica, ca. 1840 (detail)

Preserving African religions in North America proved to be very difficult. The harsh circumstances under which most slaves lived—high death rates, the separation of families and tribal groups, and the concerted effort of white owners to eradicate "heathen" (or non-Christian) customs—rendered the preservation of religious traditions difficult and often unsuccessful. Isolated songs, rhythms, movements, and beliefs in the curative powers of roots and the efficacy of a world of spirits and ancestors did survive well into the nineteenth century. But these increasingly were combined in creative ways with the various forms of Christianity to which Europeans and Americans introduced African slaves. In Latin America, where Catholicism was most prevalent, slaves mixed African beliefs and practices with Catholic rituals and theology, resulting in the formation of entirely new religions such as vaudou in Haiti (later referred to as "voodoo"), Santeria in Cuba, and Candomblé in Brazil. But in North America, slaves came into contact with the growing number of Protestant evangelical preachers, many of whom actively sought the conversion of African Americans.

enlarge

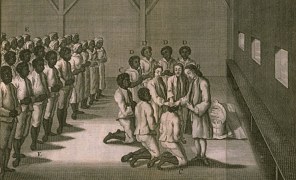

Slaves baptized in a Moravian congregation, drawing entitled "Excorcism-Baptism of the Negroes" in a German history of the Moravians (United Brethren) in Pennsylvania, 1757 (detail)

Religion and Slavery

In the decades after the American Revolution, northern states gradually began to abolish slavery, and thus sharper differences emerged in the following years between the experiences of enslaved peoples and those who were now relatively free. By 1810 the slave trade to the United States also came to an end and the slave population began to increase naturally, making way for the preservation and transmission of religious practices that were, by this time, truly "African-American."

enlarge

UVA Lib.

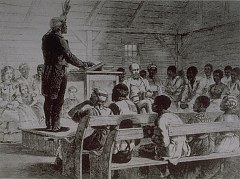

Slave preaching on a cotton plantation near Port Royal, South Carolina, engraving in The Illustrated London News, 5 Dec. 1863

On Secret Religious Meetings

"A Negro preacher delivered sermons on the plantation. Services being held in the church used by whites after their services on Sunday. The preacher must always act as a peacemaker and mouthpiece for the master, so they were told to be subservient to their masters in order to enter the Kingdom of God. But the slaves held secret meetings and had praying grounds where they met a few at a time to pray for better things." Harriet Gresham, born a slave in 1838 in South Carolina, as reported by her interviewer, ca. 1935

"[The plantation owner] would not permit them to hold religious meetings or any other kinds of meetings, but they frequently met in secret to conduct religious services. When they were caught, the 'instigators'—known or suspected—were severely flogged. Charlotte recalls how her oldest brother was whipped to death for taking part in one of the religious ceremonies. This cruel act halted the secret religious services." Charlotte Martin, born a slave in 1854 in Florida, as reported by her interviewer, 1936

"Tom Ashbie's [plantation owner] father went to one of the cabins late at night, the slaves were having a secret prayer meeting. He heard one slave ask God to change the heart of his master and deliver him from slavery so that he may enjoy freedom. Before the next day the man disappeared . . . When old man Ashbie died, just before he died he told the white Baptist minister, that he had killed Zeek for praying and that he was going to hell." Rev. Silas Jackson, born a slave in 1846 or 1847 in Virginia, as transcribed by his interviewer, 1937

scroll down/up

more excerpts

enlarge

Julia Cart

A Gullah "praise house," a surviving example of slaves' secret meeting places, and its pastor, Rev. Henderson; St. Helena Island, South Carolina, 1995

This transition coincided with the period of intense religious revivalism known as "awakenings." In the southern states increasing numbers of slaves converted to evangelical religions such as the Methodist and Baptist faiths. Many clergy within these denominations actively promoted the idea that all Christians were equal in the sight of god, a message that provided hope and sustenance to the slaves. They also encouraged worship in ways that many Africans found to be similar, or at least adaptable, to African worship patterns, with enthusiastic singing, clapping, dancing, and even spirit-possession. Still, many white owners insisted on slave attendance at white-controlled churches, since they were fearful that if slaves were allowed to worship independently they would ultimately plot rebellion against their owners. It is clear that many blacks saw these white churches, in which ministers promoted obedience to one's master as the highest religious ideal, as a mockery of the "true" Christian message of equality and liberation as they knew it.

In the slave quarters, however, African Americans organized their own "invisible institution." Through signals, passwords, and messages not discernible to whites, they called believers to "hush harbors" where they freely mixed African rhythms, singing, and beliefs with evangelical Christianity. It was here that the spirituals, with their double meanings of religious salvation and freedom from slavery, developed and flourished; and here, too, that black preachers, those who believed that God had called them to speak his Word, polished their "chanted sermons," or rhythmic, intoned style of extemporaneous preaching. Part church, part psychological refuge, and part organizing point for occasional acts of outright rebellion (Nat Turner, whose armed insurrection in Virginia in 1831 resulted in the deaths of scores of white men, women, and children, was a self-styled Baptist preacher), these meetings provided one of the few ways for enslaved African Americans to express and enact their hopes for a better future.

http://nationalhumanitiescenter.org/tserve/nineteen/nkeyinfo/aareligion.htm

what yall know about the African based frenzy dance known as the "Ring Shout" basically being the origin of "getting the holy ghost" action

Hear that Dembow/reggaeton beat they're beating/stomping out

Dont let them fool you. Some more than others, of course. Reggae, Socca, Zouk, Konpa all have significant dosages of european influence

Dont let them fool you. Some more than others, of course. Reggae, Socca, Zouk, Konpa all have significant dosages of european influence