10 mins of 2 fakkits talking.. isiah is shamelessWhat y'all think about Kenny and Isiah's take on the Hawks?

http://www.nba.com/video/channels/nba_tv/2015/01/08/20150107-gt-atlanta-hawks-discussion.nba/

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Pac's Resurrection: The Official 2014-15 Atlanta Hawks Season Thread

- Thread starter I Got Werk

- Start date

More options

Who Replied?- Joined

- Apr 30, 2012

- Messages

- 31,749

- Reputation

- 19,392

- Daps

- 120,141

- Reppin

- SOHH Icey HawkSet ByrdGang

10 mins of 2 fakkits talking.. isiah is shameless

these fukking dikkheads talking about absolutely nothing

Sly Cookin

based

Kenny and isaiah be talking philosophically about nothing. And kenny talking about "that's what they were supposed to be doing, they are a bunch of first rounders" in reference to millsap and korver

Isiah has this snobby attitude and I see why he isnt as liked by his peers

Isiah has this snobby attitude and I see why he isnt as liked by his peers

FreshFromATL

Self Made

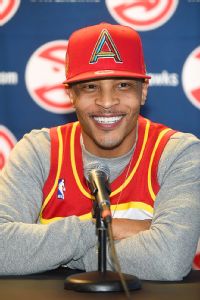

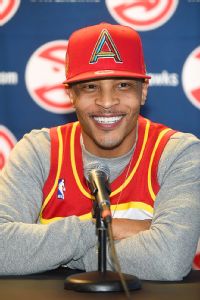

And look at this fakkit Isiah trying to antagonize Jeff after the game

www.nba.com/video/channels/nba_tv/2015/01/08/20150107-alink-jeff-teague.nba/index.html

www.nba.com/video/channels/nba_tv/2015/01/08/20150107-alink-jeff-teague.nba/index.html

This is a must read

http://espn.go.com/nba/story/_/id/12080830/reselling-hawks-atlanta

basically what we have been talking about in here the past couple of weeks

http://espn.go.com/nba/story/_/id/12080830/reselling-hawks-atlanta

basically what we have been talking about in here the past couple of weeks

http://espn.go.com/n...g-hawks-atlanta

Diagnosing the root of Atlanta's historic apathy toward its NBA franchise has long been a discussion among the city's sports fans and amateur sociologists.

The snarling traffic is often cited. Some say Atlanta is a city of transplants who brought their loyalties to other teams with them. There's the loser theory, too: Fans in Atlanta don't connect to the Hawks because the team hasn't been to the NBA's final four since 1969. The roster hasn't featured a bona fide superstar since Dominique Wilkins was shipped out of town in 1994. And the problem of the Hawks' ownership can't be understated, a group that's been consumed by in-fighting, lawsuits, messy buyouts and, more recently, inflammatory racial comments made by co-owner Bruce Levenson and general manager Danny Ferry.

Overcoming this confluence hasn't been easy for the franchise, but the fan base in Atlanta is gradually starting to take to the Hawks, their likable core of players and their fluid, pass-happy, Spurs-style offense under the direction of coach Mike Budenholzer. Attendance through 18 games at Philips Arena is up more than an average of 2,000 fans per game, to 16,015, over the same number of dates last season. An organization that, four months ago, was consumed by the fallout from Levenson and Ferry will soon have a new owner who will have an opportunity to carry the momentum forward.

But as has long been tradition in this transient city, it's an uphill climb to fill Philips Arena night in and night out and, consequently, attract the kind of name superstars who could put the Hawks on the map. LeBron James never considered Atlanta. Pau Gasol turned down a heftier offer than he received in Chicago. And that was before owner Levenson's email buried the franchise even deeper in the consciousness of the league.

As the on-court product continues its surprising ascension up the league standings, behind the scenes one of the historically most racially backward front offices in the NBA is attempting to make sports business history by embracing black fans more meaningfully than any other major pro sports team.

"If this doesn't work," says Hawks CEO Steve Koonin, "blow me out."

The Alpharetta Unicorn

When Koonin -- then only months into the job -- first read owner Bruce Levenson's now infamous email urging the team to be more welcoming to stereotypical white fans, he found the owner's take personally reprehensible.

He also found it to be precisely the opposite of what his research said, and counter to the approach the Hawks are pursuing to this day.

The notion that Levenson's "40-year-old white guy" from Atlanta's suburbs would come to Hawks games if the team would play Lynyrd Skynyrd or put more white faces on the "kiss cam" rang entirely untrue.

Long before the Levenson email became public -- for which he later apologized in a statement -- Koonin, who owns a small share of the team, and the Hawks' marketing and branding staff created a name for this line of thinking, and its creature of fantasy has become shorthand in the Hawks' offices in Centennial Tower.

"We call this the Alpharetta Unicorn," said Koonin. "This is the 55-year-old guy who's going to drive an hour from Alpharetta into the city with three buddies to go to the Hawks game. He doesn't exist. And there is no music, no kiss cam, no cheerleaders, no shooting for a free car, no bobbleheads ... nothing is going to change that."

In other words, the Hawks are coming as close to a write-off of the suburban white fan as a team possibly can.

Unlike any other city

Whatever the Hawks have done in the past, it clearly has not worked. Somehow an NBA-mad city cares almost not at all for its local team.

Atlanta consistently has some of the highest television ratings in the nation for the NBA Finals, All-Star Game and the like. When the Knicks, Lakers, Celtics, Bulls and Team LeBron come to town, Philips Arena is packed, with fans rooting for the opposition.

Atlanta isn't a lousy pro basketball town -- it's a lousy Hawks town.

AP Photo/John BazemoreA racist email by Bruce Levenson forced him to sell the Hawks and the Hawks to think differently.

Among the 122 big-four sports teams in North America, no brand may be more anemic in its local market than the Hawks. According to the ESPN Sports Poll, only 20 percent of respondents in the Atlanta area who identify themselves as NBA fans name the Hawks as their favorite team.

"There is no conversation about the Hawks in the barbershop," former Hawks guard and local pastor John Battle said. "They're talking about the Falcons."

That condition is even more true among African-American NBA fans in Atlanta; only 14 percent call the Hawks their team.

Levenson's approach clearly wouldn't help there. Battle asks, "How can you tell a person that someone doesn't want to sit by you because you scare them?"

The Hawks have fewer than 5,500 full season-ticket holders, and that includes corporate accounts whose seats are often unfilled on game nights. By contrast, the Golden State Warriors -- a team with a dismal history that plays in an old concrete slab of a building in a location far less attractive than the site of Philips Arena -- have 14,500 full season-ticket holders with a lengthy wait list, and the market demand existed long before the Splash Brothers hit the Bay Area.

The empty stands don't help the team recruit free agents either. "All things being equal, it's not a place you choose to play unless there's a good reason," said one agent. "They just don't rate."

This brings into focus a stubborn paradox: The Hawks won't attract top talent until the building is full of Hawks fans ... but the building won't be full of Hawks fans until the Hawks have top talent.

"Talent is the foundation of all of this," Koonin said. "Every question about branding, season-ticket pricing and whatnot needs to return to the question: What will attract the best talent?"

Jimmy Carter and Lou Hudson

That the Hawks sit in the middle of Atlanta's racial divide is as old as the team.

Know how Jimmy Carter first vaulted into statewide office in Georgia in 1970?

It may have had something to do with a leaflet his supporters distributed showing his opponent, Carl Sanders, being doused with champagne by former Hawks swingman Sweet Lou Hudson after the Hawks clinched the Western Division title.

Steve Brill first told the story in a 1976 issue of Harpers magazine: In the spring of 1970, two years after he and Atlanta developer Tom Cousins moved the Hawks from St. Louis to Atlanta, Sanders was in the midst of a campaign to retake the governor's mansion.

A couple of months after a photo of the celebration was printed in the paper, leaflets of the shot were distributed to white Baptist congregations and at white barbershops.

Though he won greater than 90 percent of the black vote, Sanders lost the primary to Carter by 11 points.

More than four decades before any documents were produced pleading for a Philips Arena kiss cam with fewer black smoochers or implying black players are shady, if you wanted to race-bait your political opponent in Georgia, you circulated an image of him fraternizing with large black men wearing Atlanta Hawks uniforms.

So when MARTA, Atlanta's rapid-transit system, is regarded as a nonstarter in Atlanta for fans of a certain generation who gripe about traffic ("Moving Africans Rapidly Through Atlanta"), or the environment at the game seems alien, or the product on the court feels just a little "too black," there's a traceable history.

The Tyler Perry Effect

Prior to Koonin's arrival in the Hawks' executive offices last spring, his association with the NBA had been primarily on the marketing side, first with Coca-Cola, then at Turner, where the median age of TBS and TNT viewers dropped sharply and viewership became much more diverse during his tenure as president.

While at Turner, Koonin bought and marketed "Tyler Perry's House of Payne," which became a tentpole for that growing audience.

When he landed at the Hawks, Koonin brought in Jon Marks, who, with help of Hawks vice president of brand strategy Melissa Proctor, put together a 115-page PowerPoint presentation on every facet of the Atlanta market and the people who live in it. They held focus groups across the street from Centennial Tower. All the numbers and testimonials told Koonin the same thing:

AP Photo/David GoldmanDespite a tumultuous offseason off the court, the Hawks have surged to the top of the East.

"Our bull's-eye is Atlanta proper -- African-Americans and millennials," Koonin said. "There are 2 million millennials in the area. Our other audience is African-Americans, which are 59 percent of the city of Atlanta."

As the data started to emerge, many of the discoveries produced from the experience with "House of Payne" resurfaced. Perry had wanted the show to transcend race and capture the widest audience possible for the syndication deal. He introduced white characters and broadened some of the themes, but the composition of the audience wouldn't budge.

"We tried to make 'House of Payne' more white, but trying to change the character of the show couldn't happen and wouldn't happen," Koonin said. "You can't expand to an audience that's not willing to be expanded to. That's true whether you're talking about a sitcom or the Hawks."

Twice a week on summer nights, Koonin assembled more informal focus groups at his house in Buckhead composed of his 27-year-old son, David, and a diverse group of his millennial friends and co-workers, fans and non-fans. Koonin hooked up his iPad to a 65-inch Apple TV and asked the millennials their impressions of various marketing proposals.

Over beer and homemade bagel bites, they weighed in on everything from potential smartphone Hawks apps to mockups of new team uniforms that look like a cross between something a Marvel superhero would wear and the Oregon football unis (which the research said millennials are nuts about, even if your dad thinks they're hideous).

"I wanted to get confirmation because I wasn't the target," Koonin said. "When I worked in television, I was much more of the target demographic and I could relate to the product and there was a gut sense of what worked. With the Hawks, I'm a middle-aged white Buckhead executive talking about African-Americans and millennials."

The responses from the living room research lab corroborated Koonin's experience at Turner, and his hunch that the best branding strategies going forward for the Hawks would be ones that directly contradicted the ideas in Levenson's email -- which Koonin and team knew well before that missive was leaked on Sept. 7.

AP Photo/David GoldmanHawk CEO Steve Koonin is trying to forever change the way the team sells itself to its Atlanta fanbase.

AP Photo/David GoldmanHawk CEO Steve Koonin is trying to forever change the way the team sells itself to its Atlanta fanbase.

Dinner high above Atlanta

Barely 48 hours later, Koonin hosted a dinner. Fifty floors above Midtown Atlanta in the well-appointed dining room of the law firm Alston & Bird, Koonin's guests included the Hawks' senior vice president of external affairs, David Lee; African-American political luminary Ambassador Andrew Young; businessman Greg Baranco; Raphael Warnock of the historic Ebenezer Baptist Church; and the firm's three lead lawyers investigating the Levenson affair.

At the dinner, Ambassador Young told Koonin and Lee that one of the intrinsic issues with African-American fans and the NBA is price. The product is expensive. The Hawks could perform all the outreach in the world, but those efforts would ring false if tickets weren't affordable.

"What I said was, the Falcons have one of the most integrated stadiums in the world on Sunday afternoon," Young said. "People come with their families, and the key is that you can afford eight games a season, but very few people can afford 40 games."

Young's comments informed the Hawks' approach going forward, not only with African-Americans but with millennial fans who didn't have the income of Alpharetta Unicorns.

Diagnosing the root of Atlanta's historic apathy toward its NBA franchise has long been a discussion among the city's sports fans and amateur sociologists.

The snarling traffic is often cited. Some say Atlanta is a city of transplants who brought their loyalties to other teams with them. There's the loser theory, too: Fans in Atlanta don't connect to the Hawks because the team hasn't been to the NBA's final four since 1969. The roster hasn't featured a bona fide superstar since Dominique Wilkins was shipped out of town in 1994. And the problem of the Hawks' ownership can't be understated, a group that's been consumed by in-fighting, lawsuits, messy buyouts and, more recently, inflammatory racial comments made by co-owner Bruce Levenson and general manager Danny Ferry.

Overcoming this confluence hasn't been easy for the franchise, but the fan base in Atlanta is gradually starting to take to the Hawks, their likable core of players and their fluid, pass-happy, Spurs-style offense under the direction of coach Mike Budenholzer. Attendance through 18 games at Philips Arena is up more than an average of 2,000 fans per game, to 16,015, over the same number of dates last season. An organization that, four months ago, was consumed by the fallout from Levenson and Ferry will soon have a new owner who will have an opportunity to carry the momentum forward.

But as has long been tradition in this transient city, it's an uphill climb to fill Philips Arena night in and night out and, consequently, attract the kind of name superstars who could put the Hawks on the map. LeBron James never considered Atlanta. Pau Gasol turned down a heftier offer than he received in Chicago. And that was before owner Levenson's email buried the franchise even deeper in the consciousness of the league.

As the on-court product continues its surprising ascension up the league standings, behind the scenes one of the historically most racially backward front offices in the NBA is attempting to make sports business history by embracing black fans more meaningfully than any other major pro sports team.

"If this doesn't work," says Hawks CEO Steve Koonin, "blow me out."

The Alpharetta Unicorn

When Koonin -- then only months into the job -- first read owner Bruce Levenson's now infamous email urging the team to be more welcoming to stereotypical white fans, he found the owner's take personally reprehensible.

He also found it to be precisely the opposite of what his research said, and counter to the approach the Hawks are pursuing to this day.

The notion that Levenson's "40-year-old white guy" from Atlanta's suburbs would come to Hawks games if the team would play Lynyrd Skynyrd or put more white faces on the "kiss cam" rang entirely untrue.

Long before the Levenson email became public -- for which he later apologized in a statement -- Koonin, who owns a small share of the team, and the Hawks' marketing and branding staff created a name for this line of thinking, and its creature of fantasy has become shorthand in the Hawks' offices in Centennial Tower.

"We call this the Alpharetta Unicorn," said Koonin. "This is the 55-year-old guy who's going to drive an hour from Alpharetta into the city with three buddies to go to the Hawks game. He doesn't exist. And there is no music, no kiss cam, no cheerleaders, no shooting for a free car, no bobbleheads ... nothing is going to change that."

In other words, the Hawks are coming as close to a write-off of the suburban white fan as a team possibly can.

Unlike any other city

Whatever the Hawks have done in the past, it clearly has not worked. Somehow an NBA-mad city cares almost not at all for its local team.

Atlanta consistently has some of the highest television ratings in the nation for the NBA Finals, All-Star Game and the like. When the Knicks, Lakers, Celtics, Bulls and Team LeBron come to town, Philips Arena is packed, with fans rooting for the opposition.

Atlanta isn't a lousy pro basketball town -- it's a lousy Hawks town.

AP Photo/John BazemoreA racist email by Bruce Levenson forced him to sell the Hawks and the Hawks to think differently.

Among the 122 big-four sports teams in North America, no brand may be more anemic in its local market than the Hawks. According to the ESPN Sports Poll, only 20 percent of respondents in the Atlanta area who identify themselves as NBA fans name the Hawks as their favorite team.

"There is no conversation about the Hawks in the barbershop," former Hawks guard and local pastor John Battle said. "They're talking about the Falcons."

That condition is even more true among African-American NBA fans in Atlanta; only 14 percent call the Hawks their team.

Levenson's approach clearly wouldn't help there. Battle asks, "How can you tell a person that someone doesn't want to sit by you because you scare them?"

The Hawks have fewer than 5,500 full season-ticket holders, and that includes corporate accounts whose seats are often unfilled on game nights. By contrast, the Golden State Warriors -- a team with a dismal history that plays in an old concrete slab of a building in a location far less attractive than the site of Philips Arena -- have 14,500 full season-ticket holders with a lengthy wait list, and the market demand existed long before the Splash Brothers hit the Bay Area.

The empty stands don't help the team recruit free agents either. "All things being equal, it's not a place you choose to play unless there's a good reason," said one agent. "They just don't rate."

This brings into focus a stubborn paradox: The Hawks won't attract top talent until the building is full of Hawks fans ... but the building won't be full of Hawks fans until the Hawks have top talent.

"Talent is the foundation of all of this," Koonin said. "Every question about branding, season-ticket pricing and whatnot needs to return to the question: What will attract the best talent?"

Jimmy Carter and Lou Hudson

That the Hawks sit in the middle of Atlanta's racial divide is as old as the team.

Know how Jimmy Carter first vaulted into statewide office in Georgia in 1970?

It may have had something to do with a leaflet his supporters distributed showing his opponent, Carl Sanders, being doused with champagne by former Hawks swingman Sweet Lou Hudson after the Hawks clinched the Western Division title.

Steve Brill first told the story in a 1976 issue of Harpers magazine: In the spring of 1970, two years after he and Atlanta developer Tom Cousins moved the Hawks from St. Louis to Atlanta, Sanders was in the midst of a campaign to retake the governor's mansion.

A couple of months after a photo of the celebration was printed in the paper, leaflets of the shot were distributed to white Baptist congregations and at white barbershops.

Though he won greater than 90 percent of the black vote, Sanders lost the primary to Carter by 11 points.

More than four decades before any documents were produced pleading for a Philips Arena kiss cam with fewer black smoochers or implying black players are shady, if you wanted to race-bait your political opponent in Georgia, you circulated an image of him fraternizing with large black men wearing Atlanta Hawks uniforms.

So when MARTA, Atlanta's rapid-transit system, is regarded as a nonstarter in Atlanta for fans of a certain generation who gripe about traffic ("Moving Africans Rapidly Through Atlanta"), or the environment at the game seems alien, or the product on the court feels just a little "too black," there's a traceable history.

The Tyler Perry Effect

Prior to Koonin's arrival in the Hawks' executive offices last spring, his association with the NBA had been primarily on the marketing side, first with Coca-Cola, then at Turner, where the median age of TBS and TNT viewers dropped sharply and viewership became much more diverse during his tenure as president.

While at Turner, Koonin bought and marketed "Tyler Perry's House of Payne," which became a tentpole for that growing audience.

When he landed at the Hawks, Koonin brought in Jon Marks, who, with help of Hawks vice president of brand strategy Melissa Proctor, put together a 115-page PowerPoint presentation on every facet of the Atlanta market and the people who live in it. They held focus groups across the street from Centennial Tower. All the numbers and testimonials told Koonin the same thing:

AP Photo/David GoldmanDespite a tumultuous offseason off the court, the Hawks have surged to the top of the East.

"Our bull's-eye is Atlanta proper -- African-Americans and millennials," Koonin said. "There are 2 million millennials in the area. Our other audience is African-Americans, which are 59 percent of the city of Atlanta."

As the data started to emerge, many of the discoveries produced from the experience with "House of Payne" resurfaced. Perry had wanted the show to transcend race and capture the widest audience possible for the syndication deal. He introduced white characters and broadened some of the themes, but the composition of the audience wouldn't budge.

"We tried to make 'House of Payne' more white, but trying to change the character of the show couldn't happen and wouldn't happen," Koonin said. "You can't expand to an audience that's not willing to be expanded to. That's true whether you're talking about a sitcom or the Hawks."

Twice a week on summer nights, Koonin assembled more informal focus groups at his house in Buckhead composed of his 27-year-old son, David, and a diverse group of his millennial friends and co-workers, fans and non-fans. Koonin hooked up his iPad to a 65-inch Apple TV and asked the millennials their impressions of various marketing proposals.

Over beer and homemade bagel bites, they weighed in on everything from potential smartphone Hawks apps to mockups of new team uniforms that look like a cross between something a Marvel superhero would wear and the Oregon football unis (which the research said millennials are nuts about, even if your dad thinks they're hideous).

"I wanted to get confirmation because I wasn't the target," Koonin said. "When I worked in television, I was much more of the target demographic and I could relate to the product and there was a gut sense of what worked. With the Hawks, I'm a middle-aged white Buckhead executive talking about African-Americans and millennials."

The responses from the living room research lab corroborated Koonin's experience at Turner, and his hunch that the best branding strategies going forward for the Hawks would be ones that directly contradicted the ideas in Levenson's email -- which Koonin and team knew well before that missive was leaked on Sept. 7.

Dinner high above Atlanta

Barely 48 hours later, Koonin hosted a dinner. Fifty floors above Midtown Atlanta in the well-appointed dining room of the law firm Alston & Bird, Koonin's guests included the Hawks' senior vice president of external affairs, David Lee; African-American political luminary Ambassador Andrew Young; businessman Greg Baranco; Raphael Warnock of the historic Ebenezer Baptist Church; and the firm's three lead lawyers investigating the Levenson affair.

At the dinner, Ambassador Young told Koonin and Lee that one of the intrinsic issues with African-American fans and the NBA is price. The product is expensive. The Hawks could perform all the outreach in the world, but those efforts would ring false if tickets weren't affordable.

"What I said was, the Falcons have one of the most integrated stadiums in the world on Sunday afternoon," Young said. "People come with their families, and the key is that you can afford eight games a season, but very few people can afford 40 games."

Young's comments informed the Hawks' approach going forward, not only with African-Americans but with millennial fans who didn't have the income of Alpharetta Unicorns.

The big gamble

Koonin knew these weren't monolithic audiences. For example, among African-Americans in Atlanta, there are church people and non-church people. ("You can't mass-market to an African-American audience in Atlanta.") Some millennials are governed more than others by the fear of missing out. ("The in-town crowd that wants to see T.I. sitting courtside doesn't have the same motivation as your [basketball] junkies who watch on Thursday night.")

Paras Griffin/Getty ImagesAtlanta-based rapper T.I. played pregame, halftime and postgame at the Hawks' home opener.

Though Young's remarks about economics were on point, Koonin's research told him there was still a strong base of African-American professionals and millennials in town who had money to spend, enough to bump up the Hawks' full-season ticket base from its abysmal numbers. In fact, a good amount of that money to spend is earmarked for entertainment and nights out. Those groups are spending the money -- just not on the Hawks.

"There's unequivocally enough money in the two constituencies to get 18,000 people in the house," Koonin said.

There'd better be. The Hawks, according to a confidential league memo obtained by Grantland, lost $23.9 million last season, and the arena is a mausoleum on many game nights. An NBA franchise concluding that it can close that gap without suburban money is taking a big gamble. A seat in the lower bowl for a full season runs about $5,000, a lot of coin for most 28-year-olds who haven't hit their professional stride yet.

There's a collective understanding among well-respected minds who work on the business side for NBA teams and in the league office that maintaining the value of an NBA ticket is essential to the value of the product. In short, if you're not recruiting butts to your seats, figure out what you're doing wrong without slashing ticket prices. But Koonin thinks it's crazy not to look at the Hawks' attendance record and relevant research and seriously consider adjusting the team's pricing plan, even if it's a touchy subject inside the league.

"Pricing used to be arbitrary," Koonin said. "We're doing it by science now. We're not deep discounting. We're market pricing."

According to Koonin, this principle will manifest itself not in slashing season-ticket prices, but in measures like releasing 1,500 seats for each game at $15, which was inspired by the conversation with Young at dinner. A good number of those will be premium seating distributed at random -- something Koonin calls "surprise and delight" marketing. It's not as if they don't have seats to spare.

The new south gospel

On Thanksgiving eve, those in the crowd who lingered into the third quarter of an entertaining game between the Hawks and the Toronto Raptors, who were leading the league, looked like a portrait of the new coalition. The tony club area with "yupscale" food options was bustling, the crowd well over 50 percent African-American and young relative to the club level of other pro sports venues.

"We'll go back to the seats in the fourth quarter," Reginald Austin, 37, said, sitting between his brothers, Quinton, 35, and Schrendrick, 42. "We're from the city of Atlanta. So as a city person you come to the game to indulge in what the place has to offer, to be in the in crowd. Some nights, for the bigger games, the music industry, which is big in Atlanta, the celebrities will come out. It's a spot. It's a place to be seen."

He gestures to the scene, which would've made Koonin giddy. A group of smartly dressed women are coordinating plans on their smartphones. A guy of about 30 wears a Kangol with a placard pasted to the front -- like "PRESS" on a fedora in old movies -- that reads "Justice for Mike Brown." There are virtually no families to speak of, and few if any Alpharetta Unicorns. Even though the Hawks are making a run down on the floor, the social area is hopping.

Austin and his brothers sit at a bar table, nursing pints of wheat ale with lemon wedges. After the game, they plan to head over to the nearby Leaf Cigar Lounge for a game of pool. We speak briefly about the Hawks and their inability to land a big-name superstar, but they readily admit they aren't at the game to get a look at Al Horford or Kyle Lowry.

"This is a social event," Quinton Austin said.

When the Hawks hosted a Friday night tip during theDominique Wilkins era, a game at the Omni was a total schmoozefest. Koonin, who was in his late 20s and early 30s at the time, recalls it well.

"In the '80s, when all the Jews used to inhabit the Omni, there was a social component to going to the game," Koonin, who is Jewish, said. "It was your social life. It looked like synagogue on the High Holidays. If we do the right things and create an experience that's inclusive and appealing, we can make going to the game the same kind of social event it was in the Dominique era for the African-American and young professional communities who live in town but are spending their nights and their money at hip restaurants on the Westside instead of at the arena. "

The Hawks want to build one of those well-attended, in-town churches whose congregants look like the city, sway to music that sounds current, and mingle by the full-service coffee bar before the service. They'll preach the gospel of Atlanta, a place that doesn't buy, and barely knows, tradition.

The Outkast factor

Less than three weeks after the Hawks story broke, Centennial Olympic Park -- directly across from Philips Arena -- hosted the Outkast #ATLast festival, featuring the hometown band's first show in the city in five years. The lineup included a procession of other local acts like 2 Chainz, Future and Janelle Monae. A crowd of 20,000 crammed into the park, most in their 20s and 30s, as diverse a crowd as you'll see. From the perspective of the Hawks' executive offices one block away, this was the composition of their ticket base for the next 20 years.

In his email, Levenson had cited hip-hop music during timeouts, an overwhelmingly black "scene" at bars inside Philips Arena and a crowd he estimated to be 70 percent black as problems. But rather than shelving T.I. tunes during timeouts, under Koonin, the Hawks doubled down on the Atlanta-based hip-hop artists. On opening night, T.I. played live sets -- pregame, at halftime and postgame -- to the second-largest crowd in Hawks history. The crowd was a composite of the desired audience, largely young and/or African-American, a subset of the group that populated #ATLast in September.

The research reports turned up all kinds of other findings. Millennials are far more likely than their predecessors to socialize in mixed-gender environments, yet the product was still being marketed largely as a "boys night out." The Hawks generated buzz this week by hosting "Swipe Right Night" on Wednesday, engaging the popular mobile dating app "Tinder." African-American women in Atlanta have very favorable impressions of Hawks games and are inclined to purchase single tickets, but there had never been a real effort to engage them. Since season-ticket holders of all stripes loathe being charged for preseason games, the Hawks are considering for next season hosting the games in a park adjacent to Philips Arena, and opening the gates -- FreeSeason. The Hawks also hope to collaborate with the league on a dark charcoal court, not so much to enhance the live experience, but because they want a generation of gamers to choose Atlanta when they fire up NBA2K.

AP Photo/Ron HarrisKoonin has met with local civil rights leaders to try to repair the damage done by Levenson's email.

In the works for Philips Arena: a craft beer hall, the removal of swaths of suites to make way for party decks and cheap drinks pregame. The Hawks plan to make Mike Scott, he of the emoji tattoos, the center of an emoji campaign. And the team tweeted out an offer from Koonin before Monday's 10:40 p.m. ET tip against the Los Angeles Clippers: Bosses who allowed an employee to watch the game and come in late on Tuesday morning would be treated to a ticket for Wednesday night's home game against Memphis. The stunt was clever, and the implication from the Hawks was clear: Their fans aren't the recipients of the letter, but the millennials who need the late pass.

A key component of the team's strategy will be to bring in a new generation of sponsors that actually appeal to its target audience. Seems obvious enough, but the Hawks, like most teams, have relied on the tried-and-true titans of sports sponsorship that don't really speak to younger and/or African-American fans.

"We're not going to build it the traditional way by taking out a ton of ads and blasting our message on radio like we're selling a product, because we're not," Koonin said. "We're selling an emotion."

Dating nights, microbrews, uniforms inspired by comic books -- all of this might sound like an old person's impression of what a young person wants, and that might be the case. Two prominent league business executives who think favorably of Koonin said on background that Atlanta was pretty much hopeless. They maintain that cutesy marketing to niche demographics was nothing more than whimsy that would do very little for the team's bottom line. It's still all about an arena deal, broadcast revenue, sponsorship, suites, premium seats and, of course, luring a superstar. But sure, they admire the organization's pluck.

The Hawks are up for sale, and if the team changes hands, there's no guarantee that a new ownership group won't refocus Koonin's efforts toward recapturing the audience Levenson was so anxious about. In the meantime, the Hawks are no longer wringing their hands over white flight in their arena. Through the efforts of a deep, unselfish core of players and under the direction of head coach Mike Budenholzer, the Hawks have become the NBA's newest critical darlings. Koonin is selling this like mad to a fan base that looks more like the city than the Omni's ever did.

"I know what doesn't work," Koonin said. "Chasing the Alpharetta Unicorn, trying to get the wealthy folk to buy season tickets when they've rejected the product."

we hoopin on a black court in spider man unis next year

we hoopin on a black court in spider man unis next year

Koonin knew these weren't monolithic audiences. For example, among African-Americans in Atlanta, there are church people and non-church people. ("You can't mass-market to an African-American audience in Atlanta.") Some millennials are governed more than others by the fear of missing out. ("The in-town crowd that wants to see T.I. sitting courtside doesn't have the same motivation as your [basketball] junkies who watch on Thursday night.")

Paras Griffin/Getty ImagesAtlanta-based rapper T.I. played pregame, halftime and postgame at the Hawks' home opener.

Though Young's remarks about economics were on point, Koonin's research told him there was still a strong base of African-American professionals and millennials in town who had money to spend, enough to bump up the Hawks' full-season ticket base from its abysmal numbers. In fact, a good amount of that money to spend is earmarked for entertainment and nights out. Those groups are spending the money -- just not on the Hawks.

"There's unequivocally enough money in the two constituencies to get 18,000 people in the house," Koonin said.

There'd better be. The Hawks, according to a confidential league memo obtained by Grantland, lost $23.9 million last season, and the arena is a mausoleum on many game nights. An NBA franchise concluding that it can close that gap without suburban money is taking a big gamble. A seat in the lower bowl for a full season runs about $5,000, a lot of coin for most 28-year-olds who haven't hit their professional stride yet.

There's a collective understanding among well-respected minds who work on the business side for NBA teams and in the league office that maintaining the value of an NBA ticket is essential to the value of the product. In short, if you're not recruiting butts to your seats, figure out what you're doing wrong without slashing ticket prices. But Koonin thinks it's crazy not to look at the Hawks' attendance record and relevant research and seriously consider adjusting the team's pricing plan, even if it's a touchy subject inside the league.

"Pricing used to be arbitrary," Koonin said. "We're doing it by science now. We're not deep discounting. We're market pricing."

According to Koonin, this principle will manifest itself not in slashing season-ticket prices, but in measures like releasing 1,500 seats for each game at $15, which was inspired by the conversation with Young at dinner. A good number of those will be premium seating distributed at random -- something Koonin calls "surprise and delight" marketing. It's not as if they don't have seats to spare.

The new south gospel

On Thanksgiving eve, those in the crowd who lingered into the third quarter of an entertaining game between the Hawks and the Toronto Raptors, who were leading the league, looked like a portrait of the new coalition. The tony club area with "yupscale" food options was bustling, the crowd well over 50 percent African-American and young relative to the club level of other pro sports venues.

"We'll go back to the seats in the fourth quarter," Reginald Austin, 37, said, sitting between his brothers, Quinton, 35, and Schrendrick, 42. "We're from the city of Atlanta. So as a city person you come to the game to indulge in what the place has to offer, to be in the in crowd. Some nights, for the bigger games, the music industry, which is big in Atlanta, the celebrities will come out. It's a spot. It's a place to be seen."

He gestures to the scene, which would've made Koonin giddy. A group of smartly dressed women are coordinating plans on their smartphones. A guy of about 30 wears a Kangol with a placard pasted to the front -- like "PRESS" on a fedora in old movies -- that reads "Justice for Mike Brown." There are virtually no families to speak of, and few if any Alpharetta Unicorns. Even though the Hawks are making a run down on the floor, the social area is hopping.

Austin and his brothers sit at a bar table, nursing pints of wheat ale with lemon wedges. After the game, they plan to head over to the nearby Leaf Cigar Lounge for a game of pool. We speak briefly about the Hawks and their inability to land a big-name superstar, but they readily admit they aren't at the game to get a look at Al Horford or Kyle Lowry.

"This is a social event," Quinton Austin said.

When the Hawks hosted a Friday night tip during theDominique Wilkins era, a game at the Omni was a total schmoozefest. Koonin, who was in his late 20s and early 30s at the time, recalls it well.

"In the '80s, when all the Jews used to inhabit the Omni, there was a social component to going to the game," Koonin, who is Jewish, said. "It was your social life. It looked like synagogue on the High Holidays. If we do the right things and create an experience that's inclusive and appealing, we can make going to the game the same kind of social event it was in the Dominique era for the African-American and young professional communities who live in town but are spending their nights and their money at hip restaurants on the Westside instead of at the arena. "

The Hawks want to build one of those well-attended, in-town churches whose congregants look like the city, sway to music that sounds current, and mingle by the full-service coffee bar before the service. They'll preach the gospel of Atlanta, a place that doesn't buy, and barely knows, tradition.

The Outkast factor

Less than three weeks after the Hawks story broke, Centennial Olympic Park -- directly across from Philips Arena -- hosted the Outkast #ATLast festival, featuring the hometown band's first show in the city in five years. The lineup included a procession of other local acts like 2 Chainz, Future and Janelle Monae. A crowd of 20,000 crammed into the park, most in their 20s and 30s, as diverse a crowd as you'll see. From the perspective of the Hawks' executive offices one block away, this was the composition of their ticket base for the next 20 years.

In his email, Levenson had cited hip-hop music during timeouts, an overwhelmingly black "scene" at bars inside Philips Arena and a crowd he estimated to be 70 percent black as problems. But rather than shelving T.I. tunes during timeouts, under Koonin, the Hawks doubled down on the Atlanta-based hip-hop artists. On opening night, T.I. played live sets -- pregame, at halftime and postgame -- to the second-largest crowd in Hawks history. The crowd was a composite of the desired audience, largely young and/or African-American, a subset of the group that populated #ATLast in September.

The research reports turned up all kinds of other findings. Millennials are far more likely than their predecessors to socialize in mixed-gender environments, yet the product was still being marketed largely as a "boys night out." The Hawks generated buzz this week by hosting "Swipe Right Night" on Wednesday, engaging the popular mobile dating app "Tinder." African-American women in Atlanta have very favorable impressions of Hawks games and are inclined to purchase single tickets, but there had never been a real effort to engage them. Since season-ticket holders of all stripes loathe being charged for preseason games, the Hawks are considering for next season hosting the games in a park adjacent to Philips Arena, and opening the gates -- FreeSeason. The Hawks also hope to collaborate with the league on a dark charcoal court, not so much to enhance the live experience, but because they want a generation of gamers to choose Atlanta when they fire up NBA2K.

AP Photo/Ron HarrisKoonin has met with local civil rights leaders to try to repair the damage done by Levenson's email.

In the works for Philips Arena: a craft beer hall, the removal of swaths of suites to make way for party decks and cheap drinks pregame. The Hawks plan to make Mike Scott, he of the emoji tattoos, the center of an emoji campaign. And the team tweeted out an offer from Koonin before Monday's 10:40 p.m. ET tip against the Los Angeles Clippers: Bosses who allowed an employee to watch the game and come in late on Tuesday morning would be treated to a ticket for Wednesday night's home game against Memphis. The stunt was clever, and the implication from the Hawks was clear: Their fans aren't the recipients of the letter, but the millennials who need the late pass.

A key component of the team's strategy will be to bring in a new generation of sponsors that actually appeal to its target audience. Seems obvious enough, but the Hawks, like most teams, have relied on the tried-and-true titans of sports sponsorship that don't really speak to younger and/or African-American fans.

"We're not going to build it the traditional way by taking out a ton of ads and blasting our message on radio like we're selling a product, because we're not," Koonin said. "We're selling an emotion."

Dating nights, microbrews, uniforms inspired by comic books -- all of this might sound like an old person's impression of what a young person wants, and that might be the case. Two prominent league business executives who think favorably of Koonin said on background that Atlanta was pretty much hopeless. They maintain that cutesy marketing to niche demographics was nothing more than whimsy that would do very little for the team's bottom line. It's still all about an arena deal, broadcast revenue, sponsorship, suites, premium seats and, of course, luring a superstar. But sure, they admire the organization's pluck.

The Hawks are up for sale, and if the team changes hands, there's no guarantee that a new ownership group won't refocus Koonin's efforts toward recapturing the audience Levenson was so anxious about. In the meantime, the Hawks are no longer wringing their hands over white flight in their arena. Through the efforts of a deep, unselfish core of players and under the direction of head coach Mike Budenholzer, the Hawks have become the NBA's newest critical darlings. Koonin is selling this like mad to a fan base that looks more like the city than the Omni's ever did.

"I know what doesn't work," Koonin said. "Chasing the Alpharetta Unicorn, trying to get the wealthy folk to buy season tickets when they've rejected the product."

we hoopin on a black court in spider man unis next year

we hoopin on a black court in spider man unis next year

Last edited:

Steve Koonin is the best thing to happen to this franchise since Nique left

He is going to bring this city together

He is going to bring this city together

yall dont understand how bad i want that charcoal court

yall dont understand how bad i want that charcoal court

can you give me an idea of what that would look like? or a team that comes close to that?

we'd be the first team to have itcan you give me an idea of what that would look like? or a team that comes close to that?

pending league approval. prolly like Oregon court tho with a smokey finish

pending league approval. prolly like Oregon court tho with a smokey finishFreshFromATL

Self Made

ESPN giving the Hawks props

Sly Cookin

based

That first take segment was music to my ears

we'd be the first team to have itpending league approval. prolly like Oregon court tho with a smokey finish

ahh thats a good call

tbh I wish we'd ditch the blue. Im all about Red and Black and Yellow/Gold...but Im probly alone there.

Just think we should go back to the original colors

Just think we should go back to the original colors