Locating and securing North Korea’s nuclear stockpiles and heavy weapons would take longer. Some years ago, Thomas McInerney, a retired Air Force lieutenant general and a Fox News military analyst who has been an outspoken advocate of a preventive strike, estimated with remarkable optimism that eliminating North Korea’s military threat would take 30 to 60 days.

But let’s suppose (unrealistically) that a preventive strike did take out every single one of Kim’s missiles and artillery batteries. That still leaves his huge, well-trained, and well-equipped army. A ground war against it would likely be more difficult than the first Korean War. In David Halberstam’s book

The Coldest Winter, he described the memories of Herbert “Pappy” Miller, a sergeant with the First Cavalry Division, after a battle with North Korean troops near the village of Taejon in 1950:

No matter how well you fought, there were always more. Always. They would slip behind you, cut off your avenue of retreat, and then they would hit you on the flanks. They were superb at that, Miller thought. The first wave or two would come at you with rifles, and right behind them were soldiers without rifles ready to pick up the weapons of those who had fallen and keep coming. Against an army with that many men, everyone, he thought, needed an automatic weapon.

Today, American soldiers would all have automatic weapons—but so would the enemy. The North Koreans would not just make a frontal assault, either, the way they did in 1950. They are believed to have tunnels stretching under the DMZ and into South Korea. Special forces could be inserted almost anywhere in South Korea by tunnel, aircraft, boat, or the North Korean navy’s fleet of miniature submarines. They could wreak havoc on American and South Korean air operations and defenses, and might be able to smuggle a nuclear device to detonate under Seoul itself. And for those America Firsters who might view Asian losses as acceptable, consider that there are also some 30,000 Americans on the firing lines—and that even if those lives are deemed expendable, another immediate casualty of all-out war in Korea would likely be South Korea’s booming economy, whose collapse would be felt in markets all over the world.

So the cost of even a perfect first strike would be appalling. In 1969, long before Pyongyang had missiles or nukes, the risks were bad enough that Richard Nixon—hardly a man timid about using force—opted against retaliating after two North Korean aircraft shot down a U.S. spy plane, killing all 31 Americans on board.

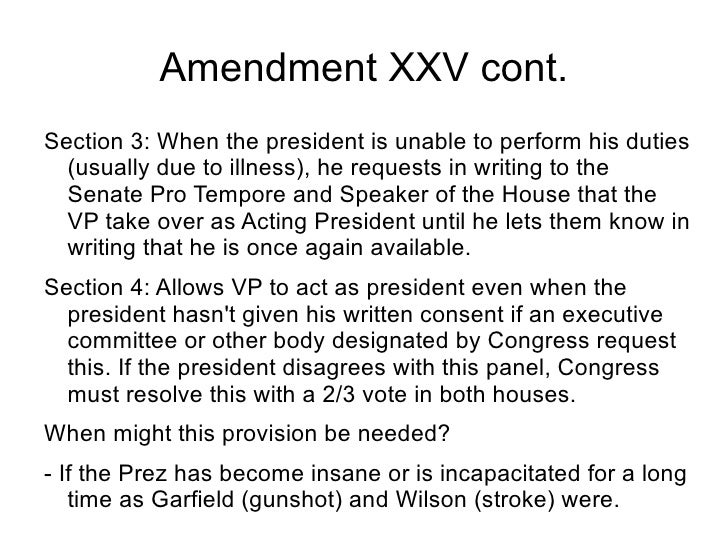

Time for Pence to deliver that late hour Coup....

Time for Pence to deliver that late hour Coup....