You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Mayor Eric Adams: King of NY Official Thread (2022-2026)

- Thread starter HoldThisL

- Start date

More options

Who Replied?ADevilYouKhow

Rhyme Reason

NYC plans to charge residential building owners for mandatory trash cans — NBC New York

Mayor Eric Adams revealed on Wednesday a new plan to put trash in containers at 95% of residential properties throughout New York City Starting next fall, buildings with nine or fewer units will be required to place all trash in secure containers. By 2026, however, the container must be official...

Why wait till next fall and he knows there’s nowhere to put them right?

ADevilYouKhow

Rhyme Reason

Manhattan Apartment Hunters Finally Get a Break With Falling Rents — Bloomberg

Prices are down from record highs, competition is easing and listing inventory has climbed, but no one should expect bargains just yet.

I

ADevilYouKhow

Rhyme Reason

New York Has Issued 14 New Food Cart Permits. 10,000 Vendors Want Them.

More than a year after the city implemented reforms to the food vendor licensing process, few have received permits, even as enforcement picks up.

Tongue Twisted: Adams Taps AI to Make City Robocalls in Languages He Doesn’t Speak

New York City law requires public documents and announcements be made available in a wide range of languages, but the mayor’s computer-assisted pretending raises alarms for some ethics experts.

Tongue Twisted: Adams Taps AI to Make City Robocalls in Languages He Doesn’t Speak

New York City law requires public documents and announcements be made available in a wide range of languages, but the mayor’s computer-assisted pretending raises alarms for some ethics experts.BY KATIE HONAN OCT. 16, 2023, 3:18 P.M.

Mayor Eric Adams is using artificial intelligence to turn himself into a polyglot: sending out robocalls with his voice to New Yorkers in a slew of languages he does not speak — and spooking out ethics and privacy advocates.

The mayor mentioned his multilingual calls at a press conference Monday announcing the new “MyCity Chatbot,” which uses AI to connect small business owners with city resources.

He unveiled the new technology with Chief Technology Officer Matt Fraser and SBS Commissioner Kevin Kim, showing how the bot can help answer questions like “how do I open a business?”

At the news conference, Adams described himself as a “techie” and former computer programmer, then later said he used the controversial tech on the city’s robocall system — sending out messages in many languages using his voice.

“Conversational AI is amazing, once you put the script in you can put it in any language you want with my voice,” he said.

“We have to be concerned about the abuse of it but we want the proper use.”

When pressed on any ethics concerns about his voice pretending to know many languages, the mayor noted the importance of speaking to all New Yorkers.

“We have to weigh something, we have to weigh that — do we want to reach all New Yorkers who have historically been locked out?” he asked.

“When we went to those hiring halls and I heard people who speak Bengali, when I heard people who speak Urdu, when I heard people who speak Spanish, and said we heard your robocall in our language — we are becoming more welcoming by utilizing tech to speak in a multitude of languages.”

A spokesperson for the mayor said they’ve reached more than 4 million New Yorkers through robocalls and sent thousands of calls in Spanish, more than 250 in Yiddish, more than 160 in Mandarin, 89 calls in Cantonese and 23 in Haitian Creole. They were mostly used for hiring halls but also promoted the city’s Rise Up NYC concerts.

‘Deeply Orwellian’

But the recordings could pose ethical issues if it makes people believe the mayor is fluent in so many tongues, surveillance and privacy experts said.“This is deeply unethical, especially on the taxpayer’s dime,” Surveillance Technology Oversight Project Executive Director Albert Fox Cahn said in a statement. “Using AI to convince New Yorkers that he speaks languages that he doesn’t is deeply Orwellian. Yes, we need announcements in all of New Yorkers’ native languages, but the deep fakes are just a creepy vanity project.”

Annika Marlen Hinze, an associate professor of political science at Fordham University, said the calls seemed “strangely deceiving.”

“It’s wonderful to make things in as many languages as you can,” she told THE CITY. “But it’s a whole other issue to pretend or insinuate that you are speaking all those languages yourself, and I see serious ethical concerns there for a mayor who does not speak multiple languages.”

Mayor Eric Adams making half a heart with an NYPD “robocop” in Times Square on Sept. 22, 2023 Credit: Alex Krales/THE CITY

Adams has embraced new technologies in his administration, particularly around public safety – from robot dogs used by the police and fire departments to a subway-patrolling “robocop.”

His announcement Monday was centered around the city’s adoption and regulation of artificial intelligence, which includes nearly 40 “actions” aimed at protecting the city and finding ways to responsibly integrate AI within agencies.

Those include: “establish a framework for AI governance that acknowledges the risks of AI, including bias and disparate impact” and “create an external advisory network to consult with stakeholders across sectors around the opportunities and challenges posed by AI.”

Power of Babble

New York City law requires most public agencies to have a “language access coordinator” and provide “telephonic interpretation” in some 100 languages. It also requires important documents and direct services be translated in 10 languages: Arabic, Urdu, French, Polish, Spanish, Chinese, Russian, Bengali, Haitian Creole and Korean.At times, though, not every agency is compliant with the translation law, as THE CITY reported during COVID vaccine distribution in 2021.

Adams is only fluent in English, and it’s not clear if he’s seriously learning any other language. On his recent trip to South and Central America, he received translation help from Manny Castro, the commissioner of the Mayor’s Office of Immigrant Affairs. And during recent appearances on Spanish-language radio, he also used various staffers to translate.

Despite being one of the most diverse cities in the world, most New York mayors have not been fluent in many languages other than English.

Former Mayor Michael Bloomberg was often ridiculed for his attempts to speak Spanish, including with a parody social media account known as “El Bloombito.” Adams’ predecessor, Bill de Blasio, would often try to speak Spanish during his news conferences, and Adams has poked fun at those attempts.

It’s not clear if Rudy Giuiliani spoke any languages other than English. Ed Koch spoke German, which came in handy when he was drafted into World War II.

Perhaps taking the linguistic cake, before being elected as mayor in 1933, Fiorello LaGuardia worked as an interpreter on Ellis Island and spoke several languages, including Italian, French German, Yiddish and Croatian.

MyCity Chatbot

MyCity Chatbot Beta

The MyCity Chatbot uses information published by the NYC Department of Small Business Services to respond to you. Other City information will be made available in the future. Please verify the MyCity Chatbot's answers with the links it provides you, and do not rely on its responses as a substitute for professional advice. Please do not provide sensitive information to the MyCity Chatbot.Examples

"How do I avoid noise violations and complaints for my construction company?""I'd like to start a new cafe and bakery in Manhattan."

"How do I apply for the MWBE program?"

Capabilities

Trained to provide you official NYC Business information.Will not use the contents of your chat history to learn new information.

Only responds to English questions for now.

Limitations

May occasionally produce incorrect, harmful or biased content.Limited knowledge of the world beyond NYC Business topics.

Trained to decline inappropriate requests.

88m3

Fast Money & Foreign Objects

The "techie" mayor fukking up as usual. Classic bullshyt artist through and through he's like a mashup of Trump and Musk

www.coindesk.com

www.coindesk.com

saw this today and got a good laugh

Sam Bankman-Fried Dined With Eric Adams at NYC Mayor’s Go-To Italian Restaurant

Erstwhile crypto titan and avowed vegan Sam Bankman-Fried was also scheduled to meet New York Gov. Kathy Hochul at The Capital Grille steakhouse, according to FBI trial testimony.

saw this today and got a good laugh

ADevilYouKhow

Rhyme Reason

Woman in Critical Condition After Man Pushes Her Into Subway Train

The 30-year-old woman was attacked at random, the police said. Officers were seeking a suspect.

NYC to lift limits on electric Uber, Lyft, and other rideshare vehicles

Shutterstock

Uber car service on the streets of New York.

By EVAN SIMKO-BEDNARSKI | esimko-bednarski@nydailynews.com | New York Daily News

PUBLISHED: October 18, 2023 at 6:11 p.m. | UPDATED: October 18, 2023 at 6:34 p.m.

New York City will no longer be limiting the number of Uber, Lyft and other rideshare cars on the road — as long as the new cars are electric.

The lifting of restrictions on the number of Taxi and Limousine Commission license plates issued to drivers working for Lyft, Uber, or other rideshare companies comes as part of the Adams administration’s goal of a fully electric or wheelchair-accessible rideshare fleet by 2030.

“We are making history, making a big bold step toward the city’s electric future,” Mayor Adams said Wednesday at a joint press conference with TLC Commissioner David Do.

“We proposed this rule because our city and our world is slipping into a deeper climate crisis,” Do said.

Under the so-called “green rides” initiative, the city will gradually mandate that Uber and Lyft dispatch a greater percentage of electric vehicles until 2030, when every nonwheelchair-accessible rideshare ride will be required to be an EV.

The city’s rideshare fleet currently consists of about 78,000 cars, which require a TLC-issued plate to legally operate. Of those, only about 2,200 are electric vehicles, and just over 6,000 are wheelchair-accessible vehicles.

The TLC has been kept from issuing new plates due to a license plate pause instituted in 2018 by the City Council and then-Mayor Bill de Blasio. The pause sought to both ease congestion on the streets and protect the yellow taxi cab industry by limiting the amount of competing rideshare cars allowed to operate.

The TLC made an exception this year, offering up 1,000 additional EV plates in March. They were gone within minutes.

Under the rule change announced Wednesday, the limit is lifted, and any would-be rideshare driver with an electric vehicle can apply for a TLC plate starting Thursday, Do said.

As previously reported by the Daily News, an unintended consequence of the cap has been the proliferation of predatory leasing arrangements, in which drivers seeking to enter the rideshare business end up paying $400-$500 a week to lease TLC-plated vehicles.

Do said he hoped the new rule could put an end to that arrangement.

“Now [drivers] can own their own small business and then they can also have a pathway to the middle class,” he said.

“If you’re putting 300‑plus dollars toward a weekly lease, that’s money out of your pocket,” he added. “We want to put more money into driver’s pockets.”

But B’hairavi Desai, head of the New York Taxi Workers Alliance, which represents both rideshare and yellow taxi drivers, said the removal of the license plate cap would destroy drivers’ financial stability.

“They’re very unceremoniously destroying a vehicle cap that was put in place at a time when there were a lot of driver suicides,” Desai told The News Wednesday. “It’s shocking to me that they would just destroy something that was so critical.”

Desai said existing Uber and Lyft drivers would bear the brunt of the new policy, being forced to buy new, expensive EVs in order to compete with an unregulated influx of new EV drivers.

She also expressed concern that they city’s charging infrastructure would not grow as quickly as the EV rideshare fleet.

“Drivers will assume that there will be enough work and enough charging infrastructure if the TLC is telling drivers to buy EVs,” she said.

Brendan Sexton, president of the Independent Drivers Guild, voiced similar worries about the city’s preparedness for an EV fleet.

“We continue to have concerns over affordability and feasibility for drivers,” Sexton said in a statement.

“Before any mandates on Uber and Lyft drivers take effect, the city must ensure that there are enough charging stations with restrooms throughout the five boroughs – and that there will be no added costs for drivers, as the mayor promised,” he added.

The IDG chief welcomed the lifting of the license plate cap, but his union has long called on the city to limit the number of rideshare drivers licenses issued by the TLC.

Do said Wednesday that the TLC was trying to move gradually toward its electrification goals.

“No rideshare vehicle and owner will be required to run out and buy an EV or wheelchair accessible vehicle tomorrow, next week or even next month,” he said.

The city intends to have electric and accessible trips constitute 5% of all rideshare hails by the end of 2024, though the commission intends to review and amend the rules if charging infrastructure isn’t up to snuff, a TLC spokesman said.

ADevilYouKhow

Rhyme Reason

Suspect in Subway Shoving Had Broken a Man’s Jaw Minutes Before

Officers were searching for the suspect, Sabir Jones, in Manhattan stations on Thursday. The woman he shoved was in critical condition.

Mayor Adams Blasts Mayor Adams's DOT Community Outreach Efforts - Streetsblog New York City

Mayor Eric Adams defended his administration's deference to drawn-out community processes that often stifle city bike and greenway projects.

nyc.streetsblog.org

nyc.streetsblog.org

Mayor Adams Blasts Mayor Adams’s DOT Community Outreach Efforts

Mayor Adams unveiled a new community engagement strategy on Tuesday: His administration is going to go door to door on Underhill Avenue to literally ask all the residents what they think about a bike network improvement.9:01 AM EDT on October 17, 2023

Mayor Eric Adams announces the city’s upcoming greenway network planning process. Photo: Dave Colon

By Dave Colon

Maybe he should be selling encyclopedias, not safer streets.

Mayor Adams, who has said that Mayor Adams and his team have been doing a poor job of conducting community outreach for street redesign projects unveiled a new strategy on Tuesday: His administration is going to go door to door on Underhill Avenue to literally ask all the residents what they think about a bike network improvement that he stalled after more than a year of ... prior community outreach.

The mayor's announcement came as park of a week during which he has defended his decisions to stall or scale-back a variety of previously approved street safety improvements on the grounds that "the community" did not feel it had been fully "heard."

"On Underhill Avenue, we're on the ground, knocking on doors, doing a survey and engaging people in communication," Adams said on Tuesday, ignoring that the Department of Transportation already did multiple rounds of community outreach on it.

This is cued up to where Streetsblog's Dave Colon asked Mayor Adams his question.

Adams told reporters on Tuesday that he wasn't happy with outreach efforts for street redesign projects, which he's been in charge of for almost two years now.

"I believe ... we have not done a good job of speaking to long-term residents on how they want the shaping of their streets to change. When you change the street you are changing the fabric of the community," he said.

Adams's comments followed a similar theme he expressed last week during an announcement of a greenway expansion effort. At that presser, Adams mentioned "community engagement" or "community planning" 16 times — and even let an opponent of some street improvements trash the Emmons Avenue protected bike lane and defend the needs of drivers.

And afterwards, he lectured to activists who called him out for his new insistence that the only real community engagement is one that objects to street safety improvements. Those comments came after Laura Shepard, an organizer for Transportation Alternatives, challenged the mayor to "show leadership" instead of ceding the pro-safety agenda to opponents who "hate change."

"Everyone has an opinion in this city, my role as mayor is to hear all these opinions," Adams told Shepard, adding, "I'm one of the best leaders you've ever seen."

"I cannot emphasize this enough," Adams had said earlier. "That is one of the top complaints we received, people did not feel as though they were engaged. We can't move at such a fast pace that we're leaving communities behind, and every community does not think the same and don't want the same but they do want to have input, and we are going to give them that input."

By definition, the city can't build a bike network if small groups of residents in each neighborhood get veto power over different segments. And as a record number of cyclists die on city streets, New York City is on pace to fall short of targets for bike lane and bus lane mileage for the second consecutive year. Meanwhile, the Department of Transportation is doing less traditional outreach than it ever has.

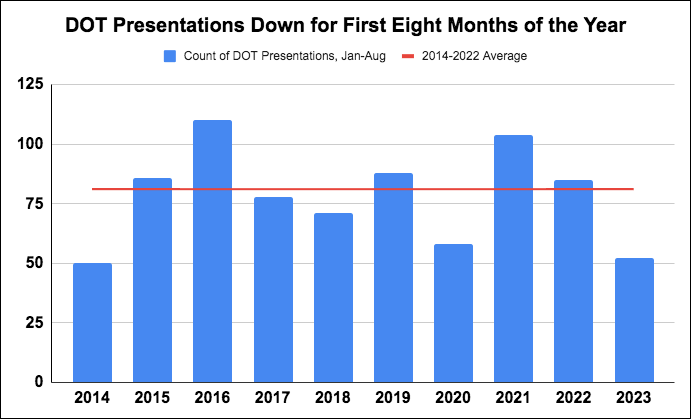

According to data compiled by Transportation Alternatives, this year the DOT has made only 52 community board presentations on projects through August, the least since the dawn of the Vision Zero era and 36 percent off the average number of presentations given every year since 2014.

Graphic: Transportation Alternatives

Community board presentations have never been a surefire way of winning neighborhood support for bike lane and bus lane projects, but they've also been the primary place the DOT has those conversations. A community board presentation is also required under a city law that discriminates against projects that benefit cyclists and pedestrians.

They also don't seem to have been replaced by something that makes Mayor Adams happy, despite the fact that he's in charge of that outreach now.

Adams pitched himself during his 2021 mayoral campaign as a difference maker — a leader who would install 150 miles of bus lanes in four years, who would "meet people where they are … and take them where you want them to be."

One reporter lasered in on this seeming contradiction last week, asking how Adams could "talk about taking [street safety changes] slow" while "you've been talking about trying to speed things up." In response, Adams got defensive, citing his championing of the (unprotected) Classon Avenue bike lane in 2017 before he was mayor because "it was the right thing to do." (Community outreach, in that case ... before he was mayor, be damned.)

Nearly seven years later, and now in the decision-maker's chair, Adams has replaced that ethos with a penchant for laughing at elected officials who want his DOT to finish projects with the same exact aims, and an overall decision-making record that's as spotty and inconsistent as his predecessor Bill de Blasio.

De Blasio, for instance, often chose to make safety improvements in the face of strong community opposition, most notably in the case of the protected bike lanes in Sunnyside and his refusal to back down on the 14th Street busway. But de Blasio also found it expedient to throw safety under the bus when the heat was on during his DOT's efforts to redesign Seventh and Eighth avenues in Sunset Park, or finish the Queens Boulevard bike lane.

Adams has also been willing to buck demands to keep streets entirely for motor vehicles in some instances. His DOT followed through on a de Blasio-era project to create the city's first protected bike lanes under elevated subway tracks in the Bronx, and has not pulled the project back even after neighborhood complaints about reduced parking.

But in so many other instances, "the best leader we've ever seen" has been willing to let an entire community engagement process play out and then delay, kill or severely curtail a project that gets through that process. Whether in the form of curtailed busway hours or bus lane and bike lane projects like Northern Boulevard, Ashland Place, Fordham Road or McGuinness Boulevard, the mayor's political allies or donors got City Hall to overrule settled projects that have gone through the public participation ringer.

So contrary to what Adams suggested about his respect for the process and his leadership, advocates said the mayor was too more a weather vane than a strong champion.

"If the mayor is saying, 'Well, we have to just wait and see what people say,' the city of New York is utterly rudderless when it comes to street change," said Bike New York Director of Advocacy Jon Orcutt, who was DOT policy director under mayors Bloomberg and de Blasio.

In addition to the the absence of Adams backing a strong policy vision, his administration also hasn't made any publicized efforts to "meet people where they are," or meet people at all. For a mayor who promised 300 miles of bike lanes and 150 miles of bus lanes, and so far has installed fewer than 50 miles of each, the speed at which he can remake the streets go hand in hand with the ability to lead and communicate.

"Anything that's hard in New York City requires strong and abiding leadership, you can't rotate in and out. You can't just throw up your hands and say, 'Well, people are complaining.' That's not governance. That's not leadership," said Orcutt.

But as Adams's City Hall pulls back on more and more projects, his fallback on process complaints rings hollow when he hasn't bothered to initiate any change in how the city conducts community outreach. So far, his City Hall and DOT has only delivered less of the same broken process.

"The mayor has the ability to put forward a vision for how these processes can happen," said Juan Restrepo, director of organizing at Transportation Alternatives, which staged a mass ride last week to protest the mayor's inaction.

"We've been looking for his leadership on this issue to support numerous projects that have already experienced vigorous community debate and received lots of community support and reflect the needs of a community for safety and for transit equity. These things are already happening — and we need the mayor to back all of the local stakeholders who have been demanding these in larger numbers opposition."

Last edited:

Advocates worry which street safety project Mayor Adams will abandon next

One high-profile project that appears to have slowed dramatically is a priority bus lane on Flatbush Avenue.

Advocates worry which street safety project Mayor Adams will abandon next

https://gothamist.com/staff/stephen-nessen

By

Stephen Nessen

Published Oct 18, 2023

By submitting your information, you're agreeing to receive communications from New York Public Radio in accordance with our Terms .

NYC Mayor's Office

We rely on your support to make local news available to all

Make your contribution now and help Gothamist thrive in 2023. Donate today

Gothamist is funded by sponsors and member donations

During his campaign for City Hall two years ago, Mayor Eric Adams promised to be a “bike mayor” who would “build out a state-of-the-art bus transit system.”

But now, as Adams approaches the halfway mark of his first term, street safety and transit advocates worry about which major street safety project will be next on the chopping block – and say they feel betrayed by the mayor.

Their concerns come after the city Department of Transportation this year drastically scaled back two long-planned street redesigns: One that would add bike lanes and reduce traffic lanes on McGuinness Boulevard in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, and another to give buses priority on Fordham Road in the Bronx.

The administration drastically reduced the ambition of both projects. Fordham Road was envisioned as a “busway” where most passenger cars would be banned. Now the administration says it will just boost enforcement against cars illegally parked in the bus lane. McGuinness Boulevard began as a project to reduce the street’s traffic lanes and add a protected bike lane stretching to the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway. The Adams administration halved the length of the bike lane at the last minute and reconfigured the design to save overnight parking spaces.

The projects faced last-minute opposition from coalitions of business groups that included the Bronx Zoo, the New York Botanical Garden and the Broadway Stages production company. Opponents argued the street safety changes would cause gridlock and reduce parking, harming their bottom lines.

The Adams administration walked back a plan to create a dedicated bus lane on Fordham Road.

NYC Department of Transportation

“I think the thing that’s most jarring is that Eric Adams poses himself as the public safety mayor, and we’re not seeing any real action on street safety,” said Jon Orcutt of the advocacy group Bike New York.

One high-profile project that appears to have slowed dramatically is a priority bus lane on Flatbush Avenue in Brooklyn. The dedicated lane would speed up the commutes of approximately 118,000 daily bus riders between Downtown Brooklyn and Kings Plaza, according to transportation department estimates.

The DOT hasn’t issued an update on its plans for the Flatbush project since January. At that time, the agency said it planned to implement the project sometime in 2023.

But that deadline won’t be met: transportation department officials now say the agency is still working on designs.

J.P. Patafio, vice president of Brooklyn buses for Transport Workers Union Local 100, said he felt betrayed by Adams’ lack of progress on new bus lanes. Local 100 endorsed Adams during his campaign.

“It's another failed or broken promise. And I don't understand it because it's easy to do,” Patafio said of giving buses priority on city streets. “It's unfortunate because this is basic infrastructure to improve public transit that predominantly serves working class New Yorkers. And I just don't see a commitment there.”

Nick Benson, a spokesperson for the city's transportation department, defended the mayor’s record and pointed to data showing that the city is on track to record the fewest pedestrian deaths in a calendar year in 2023.

While the Adams administration has had success reducing pedestrian fatalities, there have been 26 cycling deaths so far this year, the highest since 2014, when former Mayor Bill de Blasio launched his Vision Zero program with the goal of eliminating traffic deaths.

“DOT is breaking records for miles of new protected bike lanes, with nearly 100 street improvement projects recently completed or underway in addition to innovative work hardening and widening existing bike lanes,” Benson wrote in a statement.

The mayor's annual management report noted 26 miles of protected bike lanes were installed in the last fiscal year, 24 short of the City Council’s requirement of 50 miles of protected bike lanes.

“Things have been moving in the wrong direction. They're not getting better,” said City Councilmember Lincoln Restler. “I have no expectations that bold, big projects that can make our streets safer, that can save lives, that can get more people safely cycling to work, to school, et cetera, are going to be happening in this administration."

Restler said he’s learned the transportation department was directed to “no longer pursue big bike lane projects, big bus lane projects, even big city bike expansions because the political support is no longer there at City Hall.”

Spokespeople for the department and the mayor’s office did not respond directly to Restler’s assertions, or questions about how opposition from business groups affected two major street projects.

Gib Veconi, chair of the Prospect Heights Neighborhood Development Council, worried a section of Vanderbilt Avenue would lose its status as an open street, where cars are banned during most of the weekends through the end of this month.

The Vanderbilt Avenue open street.

Department of Transportation

Businesses on nearby Washington Avenue say that street has become prone to traffic jams as a result of the Vanderbilt Avenue closure.

Veconi feared that the open street could go the same way as McGuinness Boulevard and Fordham Road.

“Instead of worrying about whether somebody who wants parking spaces back might have a way of torpedoing this, we'd really like to be instead hearing from the administration about how the future is going to work and where we go with this,“ Veconi said of the volunteer-run open street, which has proven popular among both residents and businesses on Vanderbilt Avenue.

Adams administration officials said that since Adams took office, the city has installed bus lanes that affect 275,000 daily riders, including new lanes in the Bronx, on Third Avenue in Manhattan, in Downtown Brooklyn and on Northern Boulevard in Queens.

Adams recently said he didn’t want street safety projects to “steamroll communities.”

Orcutt, who served as policy director at the city transportation department under former Mayor Michael Bloomberg, said he fears the agency’s engineers and planners will be reluctant to move forward with ambitious plans.

“I think one of the biggest problems there is that for the next two years – there's going to be a chilling effect on what kind of designs DOT is going to come out with because they know they can be undermined at any moment by the bosses at City Hall,” Orcutt said. “The buck stops with Eric Adams.”

ADevilYouKhow

Rhyme Reason

An Egregious NYPD Cover-up Poses a Moral Test for Eric Adams — New York Magazine

The mayor and his police commissioner must take action against the two cops who killed Kawaski Trawick.

Similar threads

- Replies

- 525

- Views

- 31K