P2.

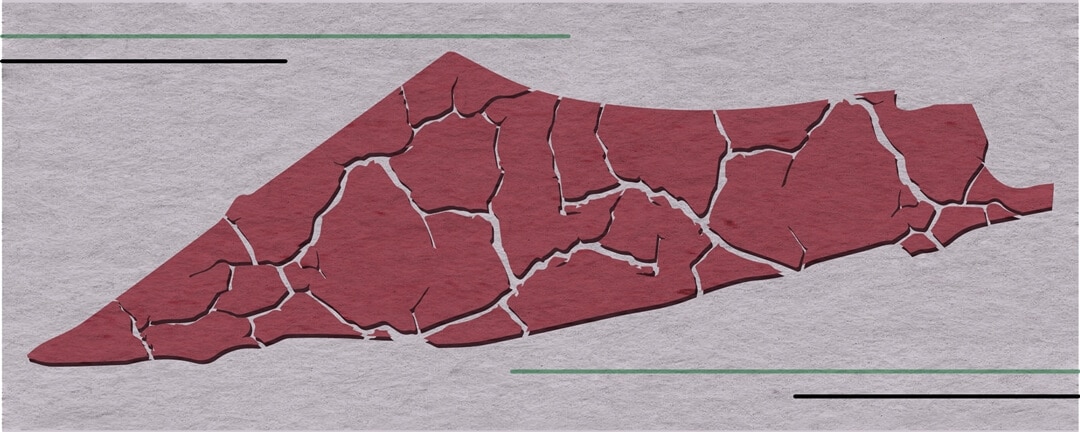

When partition is brought up in the historical sense, it is not surprising that most tend to think of the 1947 UNGA resolution. However, this was not the first partition scheme to be presented. In 1919, for example, the World Zionist Organization put forward a ‘partition’

plan, which included all of historical Palestine, parts of Lebanon, Syria and Transjordan. At the time, the Jewish population of this proposed state would not have even reached 2-3% of the total population.

Naturally, such a proposal did not see the light of day, but it is an indication of the entitlement of the Zionist movement in wanting to establish an ethnic state in an area where they were so

utterly outnumbered. To put this into context, even after waves of Jewish immigration to Palestine, and a much smaller area allocated to the Jewish state in the 1947 partition plan, the proposed Jewish state would not have had a Jewish majority without additional immigration and settlement.

As even on the eve of the Nakba, the Jewish population in mandatory Palestine was less than

a third. If we consider that most of this population arrived during the

4th and

5th Aliyot (Between 1924-1939), then the majority of those demanding partition of the land had barely been living there for 20 years at the most. To make matters worse, the UN partition plan allotted approximately

56% of the land of mandatory Palestine to the Jewish state.

Why, then, were Palestinians expected to agree to give away most of their land to a minority of recently arrived settlers? Why is the rejection of such a ridiculously unjust proposal framed as irrational or hateful?

Jabotinsky understood clearly what establishing Israel meant for the natives; he did not mince words, in his 1923 essay The Iron Wall he

wrote that:

‘Every native population in the world resists colonists as long as it has the slightest hope of being able to rid itself of the danger of being colonised’.

What was being asked of Palestinians was nothing short of rubber-stamping their own colonization with approval. Nobody should be expected to agree to that.

Yet for some, this is not seen as convincing reasoning for the rejection of partition. They acknowledge the obscene injustice of what was being asked of Palestinians, yet they argue that due to the historical persecution of the Jewish people, and fresh off the heels of the Holocaust, creating a Jewish state at the expense of Palestinians was a

historic necessity.

While such justifications serve mainly to assuage guilt, I argue that there is also a practical reason for why accepting or rejecting partition was irrelevant to the grand scheme of Zionist colonization of Palestine.

It is often brought up how the Yishuv agreed to the 1947 partition plan, showing good will and a readiness to coexist and live with their Palestinian neighbors. While this may seem true on the surface, a cursory glance at internal Yishuv meetings paints an entirely different picture.

Partition as a concept was entirely rejected, and any acceptance in public was tactical in order for the newly created Jewish state to gather its strength before expanding

[You can read more about this here].

While addressing the Zionist Executive, Ben Gurion reemphasized that any acceptance of partition would be

tactical and temporary:

“After the formation of a large army in the wake of the establishment of the state, we will abolish partition and expand to the whole of Palestine."

This was not a one-time occurrence, and neither was it only espoused by Ben Gurion. Internal debates and letters illustrate this time and time again. Even in letters to his family, Ben Gurion

wrote that “

A Jewish state is not the end but the beginning” detailing that settling the rest of Palestine depended on creating an

“elite army”. As a matter of fact, he was quite

explicit:

“I don’t regard a state in part of Palestine as the final aim of Zionism, but as a mean toward that aim.”

Chaim Weizmann

expected that:

“partition might be only a temporary arrangement for the next twenty to twenty-five years”.

So even ignoring the moral question of requiring the natives to formally green-light their own colonization, had the Palestinians agreed to partition they most likely still would not have had an independent state today. Despite what was announced in public, internal Zionist discussions make it abundantly clear that this would have never been allowed.

Partition today remains as immoral as it was when first presented, a band-aid solution and a cure for a symptom which overlooks the root cause. Any settlement that is achieved without justice or accountability merely buries the issues in exchange for short-lived quiet; but no matter how long it takes, silenced and ignored grievances will resurface.

This becomes exceedingly clear when observing the situation of our comrades in South Africa today. The demise of the Oslo accords can serve as a catalyst to challenge the fixation on the pre-1967 war borders. Reducing the question of Palestine to partition and occupation overlooks crucial components of the struggle. Many may prefer to ignore said components; however, if true justice is our goal, then they must be discussed and confronted. We must start from the beginning and reject any urges to whitewash history.

Give the Jews the north, give the Palestinians the south. Put military bases EVERYWHERE to keep both sides honest. If the US was able to force Korea to split in two in the 50s, I don't understand what the problem was. Yea, both sides would have been pissed that they lost land they thought was theirs but, fukk them they would've fallen in line. And all this money we handing to Israel should have been split equally between the two

Give the Jews the north, give the Palestinians the south. Put military bases EVERYWHERE to keep both sides honest. If the US was able to force Korea to split in two in the 50s, I don't understand what the problem was. Yea, both sides would have been pissed that they lost land they thought was theirs but, fukk them they would've fallen in line. And all this money we handing to Israel should have been split equally between the two

Israel's greatest danger is Netanyahu and his extremist minions

Israel's greatest danger is Netanyahu and his extremist minions