IllmaticDelta

Veteran

I'm more familiar with F.D. Opie's work....in fact since I couldn't find a direct passage about the Chesapeake foodways in HOTH, I decided to post an excerpt from Opie's book , Hog and Hominy

==========================================================

posting the American Regional Cuisine chapter on Chesapeake in next post

Don't think I saw it mentioned but as far as Chesapeake region goes...

Virginia peanut soup

Roanoke's favorite combo speaks to its Southern roots

Nestled in the Blue Ridge Mountains, Virginia's Roanoke Valley offers endless outdoor recreation -- everything from biking and hiking on hundreds of miles through national forests (the Appalachian Trail traverses the northern end of the valley on its 2,000-plus-mile journey from Maine to Georgia), to white water rafting and canoeing on the James River, to fishing and boating on Smith Mountain Lake. All of which, of course, will make you hungry.

If you're daytripping in the city of Roanoke, there's one dish you absolutely have to try: The peanut soup at the grand Hotel Roanoke.

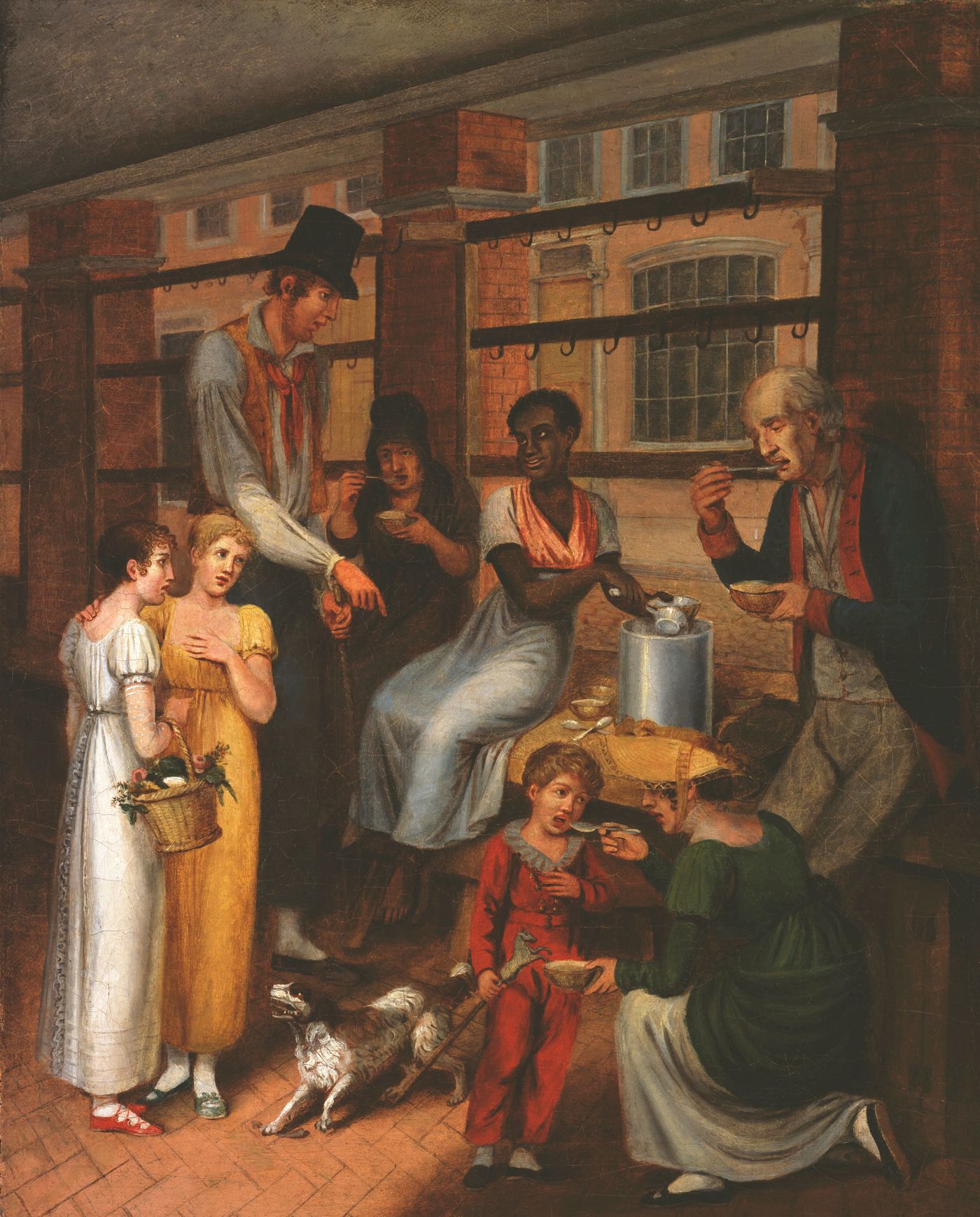

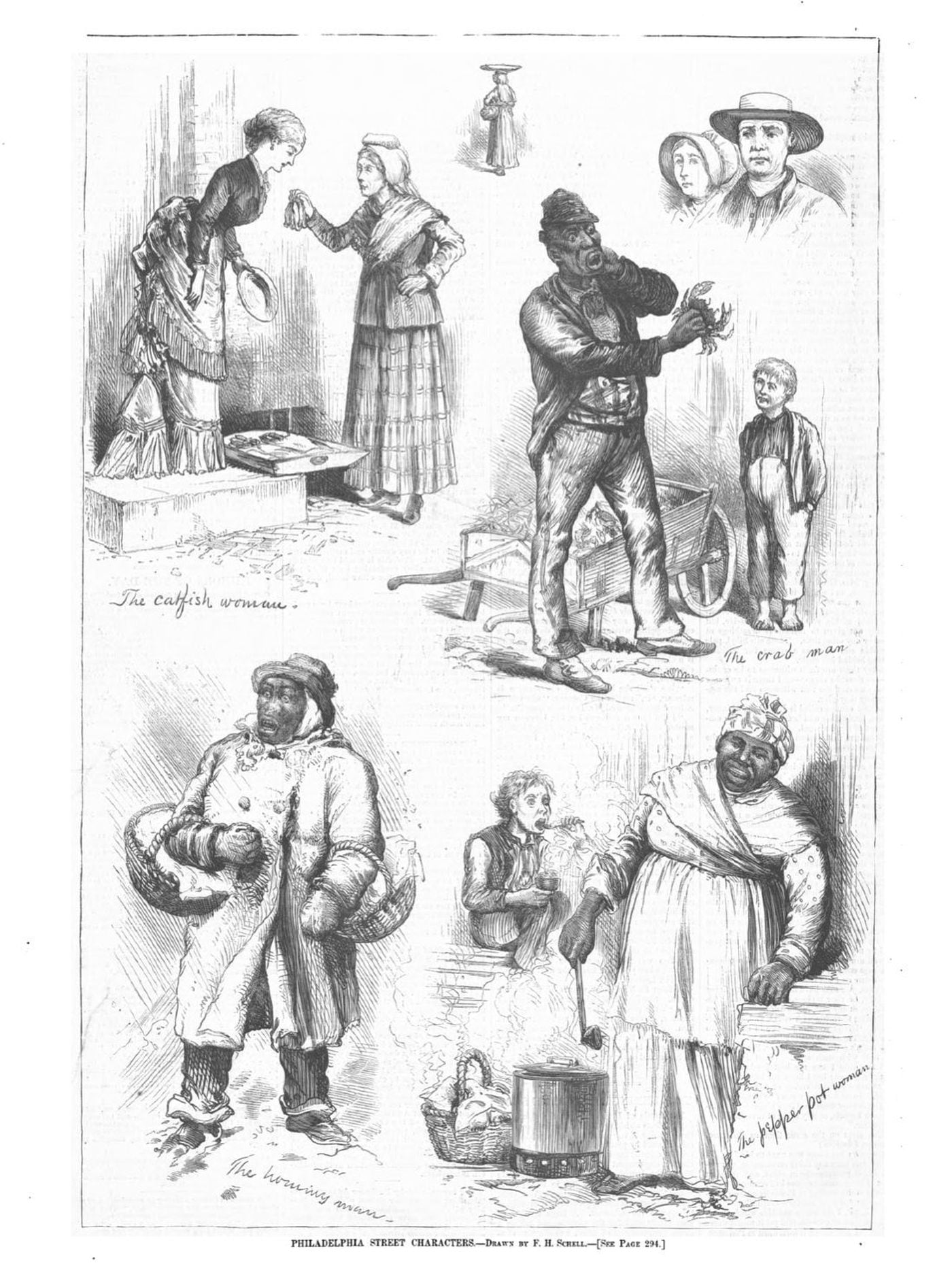

Considered a Southern delicacy, the gourmet classic dates back to the 1700s in America. But it actually has its roots in Africa. In the 1500s, Portuguese explorers carried the peanut from its native Brazil to Western Africa, where it was quickly embraced by African growers and used for stews, soups and mushes. From there, it was transported once again across the Atlantic, arriving with black-eyed peas and yams in Colonial Virginia via the slave trade.

Virginia peanut soup as we know it, says Michael Twitty, a culinary historian who specializes in African-American foodways, is a direct descendant of maafe, a peanut soup eaten by the Wolof people of Senegal and Gambia. Peanuts -- or groundnuts, as they were then known -- also were grown in Sierra Leone and Angola, where they regularly made their way into stews and spicy sauces. Before long, it found its way into plantation kitchens, "so what we're really looking at is the influence of female and male black cooks."

Some historians claim George Washington so loved peanut soup that he ate it every day, and by 1781, Thomas Jefferson, who cultivated peanuts at Monticello, was writing about them as a common crop, said Mr. Twitty. The first known recipe comes from "House and Home; or, The Carolina Housewife," a collection of Low Country recipes published in 1847 by Sarah Rutledge, a housewife from Charleston, S.C. It included a pint of oysters and peanuts ground with flour.

.

.

.

Maafe

Maafe (var. Mafé, Maffé, Maffe, sauce d'arachide (French), tigadèguèna or tigadenena (Bamana; literally 'peanut butter sauce'), or Groundnut Stew, is a stew or sauce (depending on water content) common to much of West Africa. It originates from the Mandinka and Bambara people of Mali.[1] Variants of the dish appear in the cuisine of nations throughout West Africa and Central Africa

Variations

Recipes for the stew vary wildly, but commonly include chicken, tomato, onion, garlic, cabbage, and leaf or root vegetables. In the coastal regions of Senegal, maafe is frequently made with fish. Other versions include okra, corn, carrots, cinnamon, hot peppers, paprika, black pepper, turmeric, and other spices. Maafe is traditionally served with white rice (in Senegambia), fonio in Mali, couscous (as West Africa meets the Sahara), or fufu and sweet potatoes in the more tropical areas, such as the Ivory Coast. Um'bido is a variation using greens, while Ghanaian Maafe is cooked with boiled eggs.[3] A variation of the stew, "Virginia peanut soup", even traveled with enslaved Africans to North America.