A. Fuel Price Hike

In July 2018, simmering tensions exploded into massive protests after President Moïse announced a fuel-price hike that would have devastated Haiti’s poor majority

17 who are already struggling to survive on $2 per day.

18 The price increases — between 38% and 51% — were required earlier that year by the International Monetary Fund as a condition of its bailout of the Haitian Government.19 President Moïse responded to the protests by suspending the price hike and replacing then Prime Minister Jack Guy Lafontant to placate protesters.20 But he did not take further measures to address the rising costs of living and predatory corruption that made the price hikes so devastating in the first place. The failure to address these deeper drivers made the situation ripe for further uprisings. IJDH Director Brian Concannon warned at the time that “if Haiti’s government does not confront poverty and corruption, more unrest will follow.”21

B. PetroCaribe Corruption Scandal

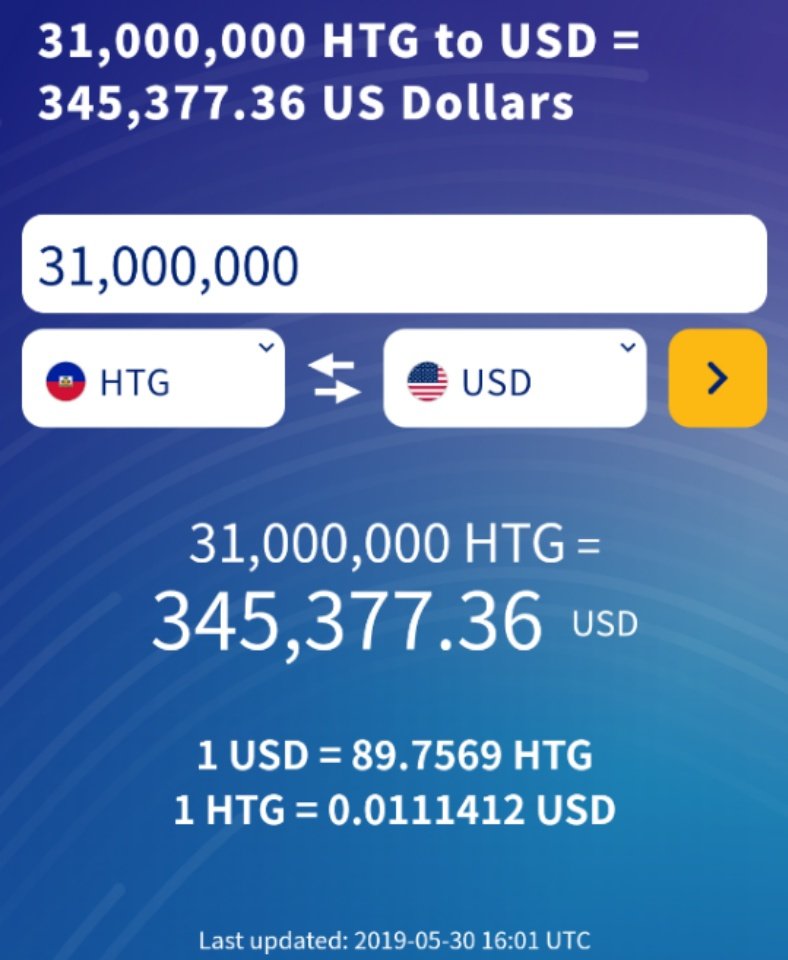

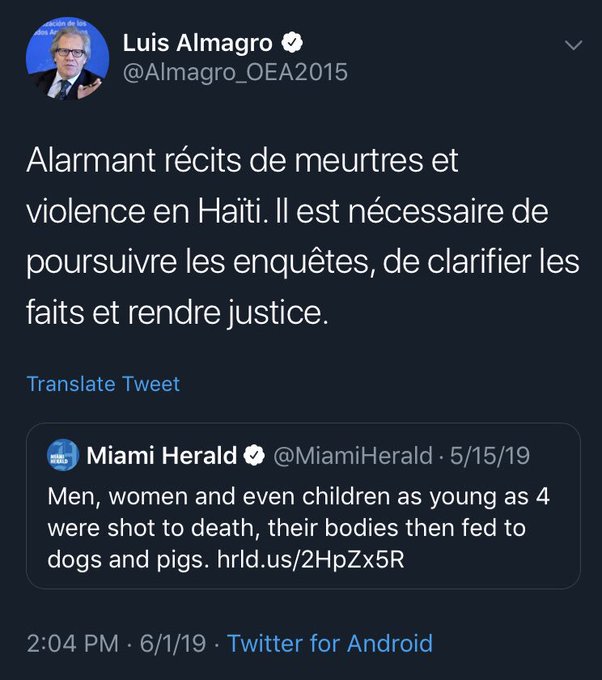

Protests erupted again the following month, and have now coalesced around demands for accountability for the disappearance of an estimated $3.8 billion from the PetroCaribe fund, which holds revenue from a low-interest fuel loan program from Venezuela intended to finance socioeconomic development in Haiti.22 Official investigations have implicated much of Haiti’s political class, including numerous high-level officials throughout recent administrations, in the corruption scandal.

23 In November 2017, the Haitian Senate’s Special Commission of Investigation released a 650-page report that identified 15 former ministers and top officials suspected of corruption and misappropriation of the public funds, resulting in the loss of $1.7 billion.24 From May 2011 to January 2016, President Moïse’s predecessor and patron President Michel Martelly allegedly spent about $1.256 billion of the $1.7 billion (74% of all the money the Haitian government took over a decade from the PetroCaribe Fund) to finance projects that were either not finished or never started.25President Moïse is also personally implicated, accused of overbilling the government on a $100,000 contract to install solar lamps back in 2013.26

The implication of so many high-level officials in and close to this government has thwarted accountability at every level of government, even within supposedly autonomous agencies.27 At the legislative level, the Senate obstructed investigations by blocking a vote on the Commission report for four months.28 Senators with the majority party then passed a resolution condemning the report as politically-motivated in a clandestine session convened after opposition senators had left the building.29 In a move described as “exposing the cowardice of the Senate”, the resolution referred the dossier to the

Cour Superieur des Comptes et du Contentieux Administratif (CSCCA), a governmental body that had already signed off on the contracts in questions at the time they were awarded.30 The CSCCA did issue an audit report in January 2019 that appears to be a serious attempt to advance the investigation.31 The report demonstrated that many state entities are delaying or denying the cooperation that the CSCCA needs to complete its work. Because of this, the CSCCA only addressed projects where it had enough information. In April 2019, the CSCCA announced that a follow-up report was further delayed due to inadequate resources to complete the investigation.32 At the executive level, President Moïse unlawfully fired the director of UCREF, the financial crimes unit that produced an investigative report during the 2016 elections implicating President Moïse in money laundering, and replaced him with an unlawful “interim” director more favorable to Moïse.

33 The new Parliament dominated by President Moïse’s allies then passed a law that granted the executive de facto control over the entity, greatly undermining its independence.34 Finally, at the judicial level, criminal prosecutions have been slow to advance. As of October 2018, private citizens had filed over 60 complaints in court, which are now before an investigative judge assigned to the matter.35 According to a March 26, 2019 statement from civil society group Fondasyon Je Klere, the judge ordered the freezing of bank accounts associated with some of the individuals and companies implicated in the scandal, including Haiti’s former Prime Minister Laurent Lamothe and several former ministers.

36 But no officials have been held criminally accountable for wrongdoing related to PetroCaribe to date.37

President Moïse unlawfully fired Sonel Jean François (above), the director of UCREF, the financial crimes unit that produced an investigative report during the 2016 elections implicating President Moïse in money laundering.

Civil society is pushing for accountability from the streets in Haiti to social media around the world.38 Massive protests were held in August, November and December 2018, and February 2019, and are expected to continue. President Moïse has mostly responded to the protests with silence, declining to address the concerns of the opposition. During the ten-day lockdown in February, he waited until day four to issue a five-minute statement that was widely criticized for lacking in substance.39

C. Arrest and Release of Foreign Mercenaries

At the height of the February protests, the arrest and subsequent unlawful release to the United States of seven heavily armed foreign mercenaries further roiled the nation.40Haitian police intercepted the men in an unlicensed vehicle with a cache of automatic rifles and pistols outside the Central Bank.41 The men allegedly told the police they were “on a government mission.”42 They were arrested on weapons trafficking charges and held in Haitian jail. On the order of the Minister of Justice, a close ally of President Moïse, they were later transferred into U.S. custody and taken to Miami, where U.S. authorities released them without charge.43 One of the men involved, ex-Navy SEAL Chris Osman, publicly lauded the release operation in a social media post, stating “I have seen the weight of the U.S. Government at work and it’s a glorious thing”.44

While many of the details remain murky, subsequent journalistic investigations suggest that the men were in Haiti to provide security for a Haitian businessman with close ties to the President, who was moving $80 million from the PetroCaribe fund into an account that the President controls in order to further consolidate power.45 Osman has publicly contested this account, countering that the group’s understanding of the mission was to provide security protection during the signing of a multimillion dollar infrastructure contract.46 While the true motives may not be known, the incident — eerily evocative of the U.S. marine occupation of Haiti in 1914 that started with a seizure of Haiti’s gold reserves at the Central Bank47 – sowed further anxiety at a time of intense insecurity in Haiti. The U.S. government’s interference with the Haitian justice system sparked particular outrage,48 and contravened the U.S.’s own policy of not intervening when U.S. citizens are before the Haitian criminal justice system.49 As the

Bureau des Avocats Internationauxwrote in a letter to the U.S. Ambassador denouncing the interference, the action undermined stability, sovereignty and the rule of law.50 It was a vivid reminder of the ways in which power interests operate above the law in Haiti, thus adding fuel to an already roiling fire.

(To be continued)