Her party won the most votes, but lost around 8% compared to last election. This is the worst result for her party in its existence and she is now severely weakened. Since the 33% her party got are not nearly enough to govern alone, she needs to form a coalition government. However, her former social democratic coalition partners (and second strongest party) already said they will not continue the coalition, in Order to recover from their historic defeat with barely 20% of the votes. That means that Merkel will have to turn to the smaller liberal party as well as the greens, who are on very different ends of the political spectrum. Negotiations will be difficult and probably take two or three month. If they fail, there might be reelections.So Merkel won re-election?

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

German Federal Elections (Merkel remains Chancellor, AfD enters Bundestag, SPD heads the Opposition)

- Thread starter FAH1223

- Start date

More options

Who Replied?Her party won the most votes, but lost around 8% compared to last election. This is the worst result for her party in its existence and she is now severely weakened. Since the 33% her party got are not nearly enough to govern alone, she needs to form a coalition government. However, her former social democratic coalition partners (and second strongest party) already said they will not continue the coalition, in Order to recover from their historic defeat with barely 20% of the votes. That means that Merkel will have to turn to the smaller liberal party as well as the greens, who are on very different ends of the political spectrum. Negotiations will be difficult and probably take two or three month. If they fail, there might be reelections.

Upstart AfD Shakes Up German Election—but It Has an Espionage Backstory

Upstart AfD Shakes Up German Election—but It Has an Espionage Backstory

By John R. Schindler • 09/25/17 4:00pm

Opinion

Leadership member of the hard-right party AfD (Alternative für Deutschland) Alice Weidel addresses a press conference on the day after the German General elections on September 25, 2017 in Berlin. JOHN MACDOUGALL/AFP/Getty Images

Germany went to the polls on Sunday to elect a new federal parliament—and a new national government—and the results stunned Europe and the world. Although center-right Chancellor Angela Merkel won a fourth term in office, since her party came out on top in the vote tallies, in truth the election stands as a stern rebuke of her and her party’s governance since 2005. For a politician widely considered the de facto leader of the European Union, and even hailed as the “leader of the free world” by some, including Hillary Clinton, this is a serious setback.

Her Christian Democratic Union (CDU) received one-third of the votes, 33 percent, far ahead of the second-place Social Democrats (SPD) with 20.6 percent, but for both parties this represented a big drop-off since the last elections. In 2013, the CDU and the SPD got 37 and 29 percent, respectively, and Sunday’s tallies are the lowest for both parties since the establishment of the Federal Republic in 1949, out of the ashes of Nazism and the Second World War.

The big news here is the rise of the Alternative for Germany (AfD). Founded only four years ago, this new right-wing party barely competed in the 2013 election, garnering only 1.9 percent of the vote, but on Sunday the upstart AfD won 12.6 percent, which will give them 94 seats in the incoming parliament in Berlin, what Germans call the Bundestag. For the first time since 1990, a new party will be seated in the Bundestag, and it’s on the far-right. The AfD did especially well in economically lagging regions of the former East Germany, where 26 percent of men voted for the party.

Several other parties hovered around the 10-percent mark, including the libertarian-leaning Free Democrats (10.7), the former East German Communists rebranded as Die Linke (9.2), and the environmentalist Greens (8.9). As the chastened Social Democrats show no interest in a grand coalition with Merkel’s Christian Democrats, the only way the chancellor can form a government will be in coalition with some of these smaller parties. The likeliest outcome is the so-called “Jamaica” coalition from the colors of that country’s flag: black for the CDU, yellow for the Free Democrats, and green (obviously) for the Greens.

Merkel will keep the upstart AfD out of government at all costs, viewing them as pariahs and extremists. Ironically, this new rival is very much her own creation, inadvertently. Born out of frustration with Berlin’s costly bailouts of Greece and other bankrupt EU states, the AfD takes its name from one of Merkel’s less popular aphorisms, when she repeatedly stated Germany had “no alternative” but to financially bail out Southern Europe from its insolvency.

This was far from popular with many Germans, a notoriously frugal bunch that loathes debt; as late as 2011, only one-third of Germans had a credit card, and most personal transactions are still in cash. Merkel then made things worse by opening Germany’s doors to migrants in 2015, which made her deeply unpopular with many working-class Germans. The arrival of two million migrants in 2015—relative to population, this would be like the U.S. taking in eight million migrants in 12 months—has caused serious political heartache in certain quarters.

That anger made up some of the AfD’s appeal on Sunday. There are definite wings of the party. Some supporters are financially-minded, worried about the cost of Germany’s dragging along the EU and its vast debts. Others fret about migrants, many of them Muslim, bringing crime, welfare skimming, and terrorism to the country. Then there’s the hard-right element of the party, people who are uncomfortably sympathetic to Germany’s troubled past.

In other words, there are neo-Nazis lurking in the AfD. This is a serious matter, since unlike in America, it’s not legal to fly Nazi flags and shout Hitlerian slogans in public. There is no free speech in Germany about such touchy matters, and people really do wind up in jail for acting out their Nazi fantasies. The march-turned-riot this country witnessed in Charlottesville in August would have been shut down in Germany the minute anybody unfurled a swastika.

Exactly how many neo-Nazis there are in AfD ranks is a tricky question. Some party bigwigs have walked close to the line. Alexander Gauland, a party leader, recently suggested that Germany should act like any other country and be “proud” of its soldiers in both world wars. Such a comment, which would be uncontroversial in most places, was greeted with outrage in Germany, where any public esteem for the Nazi period is verboten.

If the AfD is harboring neo-Nazis, this is a matter for Germany’s intelligence services too. Since the creation of the Federal Republic, the domestic intelligence agency, the mouthful Office for the Protection of the Constitution (BfV), has monitored political extremists looking for unhealthy dissent, left and right. Uncovering subversion—specifically anything that threatens Germany’s democratic values—is one of the BfV’s main jobs, and it has watched the AfD closely since its birth.

Last month, Thomas de Maizière, Germany’s interior minister, frankly admitted that the security services had their eye on the AfD, looking for subversion. Although the party on the whole was “not extremist,” less moderate elements in the AfD did merit examination, de Maizière explained. At the same time, after a review of AfD online activities in part of the former East Germany, the security service concluded that the party was substantially right-wing but not engaged in openly subversive activities.

Germany has shut down neo-Nazi parties before. In 1952, the authorities banned the Socialist Reich Party, which saw itself as Hitler’s heirs and was staffed by former Nazis. It also had the secret backing of Soviet intelligence, which sought to manipulate West German politics during the Cold War.

More recently, the standard-bearer for such views has been the National Democratic Party (NPD). Founded in 1964, it’s a fringe party that has never won any seats in the Bundestag, although it’s intermittently won seats at the state level in Germany. The NPD doesn’t make much effort to hide its Hitlerian sympathies but usually stays on the right side of Germany’s restrictive laws on such matters, if only just.

The party has been of intense concern to the BfV from its birth, and here’s where things get interesting: German authorities have tried more than once to ban the NPD on the grounds that its aims are undemocratic, yet all efforts have failed to stand up in court. The biggest push came between 2001 and 2003, and the case went to Germany’s highest court. There the NPD triumphed on the revealing grounds that, since the party was so filled with BfV agents, it was impossible for the court to assess what the NPD really stood for. Many of its most Nazified members turned out to be clandestine government operatives. The BfV, in effect, was in control of the NPD, and its numerous agents provocateurs were running the show.

Given this recent history, questions must be raised about the AfD as well, not least because the party has worrisome ties to Russia. Party higher-ups are enthusiastic fans of Vladimir Putin, while Kremlin outlets like RT and Sputnik laud the party on a regular basis. Moreover, the election campaign witnessed an explosion of pro-AfD activity online, including Twitter bots, emanating from Russia—just as the Kremlin did in the United States last year.

To be fair, the former Communists of Die Linke are every bit as Russophile as the AfD—which means that Putin has friends on the left and right of Merkel, amounting to 22 percent of the vote on Sunday—while top SPD officials take Kremlin money without any concern for appearances or conflicts of interest. Germany has a problem with illicit Kremlin influence that extends far beyond just the AfD.

That said, the BfV’s interest in the AfD, now the country’s third-biggest political party, encompasses counterintelligence concerns as much as worries about extremism. The arrival of the AfD in the Bundestag will shake up German politics in a manner that’s not been seen in decades, even though the party will not be in government. They will force debate on issues that Chancellor Merkel would prefer to avoid, above all migration and assimilation of newcomers.

It would therefore be wise to watch how the AfD reacts to its newfound limelight. Already cracks are appearing in the party. Less than 24 hours after electoral triumph, Frauke Petry, the leader of the AfD’s more moderate wing, announced she would not take her parliamentary seat, citing chaos inside the party. This stunning news may push the AfD even further to the right. Expect more bumps in this road.

John Schindler is a security expert and former National Security Agency analyst and counterintelligence officer. A specialist in espionage and terrorism, he’s also been a Navy officer and a War College professor. He’s published four books and is on Twitter at @20committee.

German defeat: Workers walk out on Europe’s mainstream left

Divorce between working class and center-left spelled defeat for Social Democrats.

By PAUL TAYLOR

9/26/17, 4:04 AM CET

The SPD hemorrhaged support in the former industrial bastions in the Ruhr region | Lukas Schulze/Getty Images

Once, the West German SPD boasted a rock-solid base of unionized, industrial, working-class voters. Allied with the progressive middle class and young people, the party of Willy Brandt and Helmut Schmidt polled close to or above 40 percent from 1965 to 1983. As recently as 2002, it still won 38.5 percent in reunited Germany, sufficient to lead a governing coalition.

On Sunday, the list led by former European Parliament President Martin Schulz polled just 20.5 percent — the SPD’s worst score since World War II — due to mass defections in traditional heartlands.

The party’s biggest setbacks were in northern cities such as Hamburg and Bremen and former industrial bastions in the Ruhr region of western Germany such as Essen, Gelsenkirchen and Dortmund, where losses of 8-10 percentage points were triple the national average.

The slump mirrors the catastrophic results of moderate-left parties around much of Western Europe, as traditional supporters defect to populist anti-immigration movements, hard-left anti-globalization forces or abstention.

For the SPD, the decline began when the German Greens started to peel away “lifestyle liberals” in the 1980s.

In Germany, pollster Infratest Dimap estimated that former SPD voters defected in almost equal numbers to the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD), the liberal Free Democrats (FDP), the hard-left Die Linke and the Greens. The nativist AfD — a sister party to Marine Le Pen’s National Front in France and the Dutch Freedom Party of Geert Wilders — polled 12.6 percent to enter the Bundestag for the first time, riding a wave of hostility to immigration, refugees, Islam and the European Union.

It’s a trend that has played out across the Continent. France’s Socialists and the Dutch Labor Party both suffered decimating defeats this year, bleeding support to anti-immigration Islamophobes, Euroskeptics, centrist modernizers and hard-left anti-globalization parties. Meanwhile, Spain’s Socialists have lost ground to the far-left Podemos and to Catalan nationalists.

The same forces led many lifelong working-class British Labour Party voters to vote for the U.K. to leave the EU. And there’s an echo in the U.S., where “America first” President Donald Trump won over many white working-class voters from the Democrats with a nationalist, anti-immigration, anti-globalization campaign.

Identity politics

According to Piero Ignazi, a lecturer in comparative politics at Italy’s Bologna University, the main battleground of Western politics has shifted away from class-based issues to matters of identity, culture and lifestyle, partly because of the success of social-democratic welfare policies in improving living standards and working conditions.

“Political conflict in the West since the end of the 20th century was based not only on class struggle but also on cultural issues, cosmopolitanism versus closed nationalism,” he said at a debate at the Lector in Fabula European cultural festival in Conversano, Italy. “Workers no longer live and work in the same conditions in Germany, France, Italy or Greece. Traditional workers don’t feel represented anymore and ask why left-wing parties no longer deal with their problems.”

Martin Schulz was at the top of the list as the SPD crashed to their worst result in 20 years | Sean Gallup/Getty Images

For the SPD, the decline began when the German Greens started to peel away “lifestyle liberals” — younger, pacifist and environmentalist voters — in the 1980s. Having lost the organic muesli-eaters, the party went on to alienate beer-and-wurst Sozis. Starting in 2004, many working-class and leftist voters defected to Die Linke in protest of former SPD Chancellor Gerhard Schröder’s neoliberal reforms of labor laws, unemployment benefits and pensions.

Schröder’s Agenda 2010 reforms laid the foundation for Germany’s economic recovery over the last decade, but they hurt many core left-wing voters and fostered a generation of “mini-jobs.” More recently, the SPD’s embrace of multiculturalism and gay marriage cost it some traditional supporters.

“The old working class is disappearing historically, and therefore left-wing parties need to look for other voter groups in the middle classes,” said Colin Crouch, emeritus professor of sociology at Britain’s Warwick University.

After serving as junior partners in governments led by conservative Chancellor Angela Merkel for eight of the last 12 years, the Social Democrats were unable to present themselves as a credible alternative.

If Infratest Dimap’s model is right, nearly 900,000 SPD voters switched on Sunday to the AfD and the FDP. While those two parties have very different economic philosophies, they share a common aversion to Merkel’s decision to welcome more than 1.5 million refugees and other migrants in 2015-2016 and a refusal to help weaker eurozone partners financially.

Portuguese Prime Minister Antonio Costa currently leads a successful left-wing government | Mario Cruz/EPA

As a result, the SPD joins the ranks of other European center-left parties at risk of tearing themselves apart — and possibly losing their souls — over how to win back the voters they lost.

Left behind?

Austria’s Socialist Party has adopted some of the anti-immigration rhetoric of the populist Freedom Party in order to survive. In Britain, Jeremy Corbyn has embraced Brexit and curbing immigration, as well as old-style tax-and-spend and nationalization policies, to try to revive Labour’s fortunes. He is aided by a first-past-the-post electoral system that gives a premium to big parties and punishes fragmentation.

On the Continent, where proportional representation dominates, the risks of a splintering of the left are far greater. In France, far-left leader Jean-Luc Mélenchon is positioning his anti-globalization, Euroskeptic movement as the sole real opposition to Macron’s labor market liberalization, at the risk of driving Socialist reformers into Macron’s arms.

The SPD may win back some lost voters simply by going into opposition and restoring a clearer left-right divide — but the four-way split in defections and the shifting class base of its electorate makes its task ever more complicated.

If the party is to make itself relevant to German workers, it will have to grapple with the changing nature of society and of work, as well as declining unionization and party membership.

“Whichever way the SPD moves, it’s going to lose people on the other side” — Researcher Andrew Watt

The questions the SPD will need to answer include: whether to protect job-for-life incumbents or favor precarious job-creation for the unemployed; how to provide credible social rights for a growing army of gig workers in service industries; how to share the cost of the welfare state in an aging society; and how to reconcile a diverse, tolerant community with a more traditional national identity.

Andrew Watt, a researcher with the German trade unions’ Hans-Böckler Foundation, suggests the left will need two parties that compete against each other but are able to compromise and form coalitions together. He pointed to the success of Portuguese Prime Minister Antonio Costa, who leads a minority Socialist government supported by two smaller communist and leftist parties.

“You have to have two fishing boats. One that tries to get back traditional voters in competition with AfD, Die Linke, Mélenchon and Front National,” he said. “And another party that competes with the CDU and the FDP, or with Macron, for the more comfortably-off working class, professionals, creatives and public sector workers.”

“You can’t say ‘we just have to push left now,’” he added. “Whichever way the SPD moves, it’s going to lose people on the other side.”

German defeat: Workers walk out on Europe’s mainstream left

Divorce between working class and center-left spelled defeat for Social Democrats.

By PAUL TAYLOR

9/26/17, 4:04 AM CET

The SPD hemorrhaged support in the former industrial bastions in the Ruhr region | Lukas Schulze/Getty Images

Once, the West German SPD boasted a rock-solid base of unionized, industrial, working-class voters. Allied with the progressive middle class and young people, the party of Willy Brandt and Helmut Schmidt polled close to or above 40 percent from 1965 to 1983. As recently as 2002, it still won 38.5 percent in reunited Germany, sufficient to lead a governing coalition.

On Sunday, the list led by former European Parliament President Martin Schulz polled just 20.5 percent — the SPD’s worst score since World War II — due to mass defections in traditional heartlands.

The party’s biggest setbacks were in northern cities such as Hamburg and Bremen and former industrial bastions in the Ruhr region of western Germany such as Essen, Gelsenkirchen and Dortmund, where losses of 8-10 percentage points were triple the national average.

The slump mirrors the catastrophic results of moderate-left parties around much of Western Europe, as traditional supporters defect to populist anti-immigration movements, hard-left anti-globalization forces or abstention.

For the SPD, the decline began when the German Greens started to peel away “lifestyle liberals” in the 1980s.

In Germany, pollster Infratest Dimap estimated that former SPD voters defected in almost equal numbers to the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD), the liberal Free Democrats (FDP), the hard-left Die Linke and the Greens. The nativist AfD — a sister party to Marine Le Pen’s National Front in France and the Dutch Freedom Party of Geert Wilders — polled 12.6 percent to enter the Bundestag for the first time, riding a wave of hostility to immigration, refugees, Islam and the European Union.

It’s a trend that has played out across the Continent. France’s Socialists and the Dutch Labor Party both suffered decimating defeats this year, bleeding support to anti-immigration Islamophobes, Euroskeptics, centrist modernizers and hard-left anti-globalization parties. Meanwhile, Spain’s Socialists have lost ground to the far-left Podemos and to Catalan nationalists.

The same forces led many lifelong working-class British Labour Party voters to vote for the U.K. to leave the EU. And there’s an echo in the U.S., where “America first” President Donald Trump won over many white working-class voters from the Democrats with a nationalist, anti-immigration, anti-globalization campaign.

Identity politics

According to Piero Ignazi, a lecturer in comparative politics at Italy’s Bologna University, the main battleground of Western politics has shifted away from class-based issues to matters of identity, culture and lifestyle, partly because of the success of social-democratic welfare policies in improving living standards and working conditions.

“Political conflict in the West since the end of the 20th century was based not only on class struggle but also on cultural issues, cosmopolitanism versus closed nationalism,” he said at a debate at the Lector in Fabula European cultural festival in Conversano, Italy. “Workers no longer live and work in the same conditions in Germany, France, Italy or Greece. Traditional workers don’t feel represented anymore and ask why left-wing parties no longer deal with their problems.”

Martin Schulz was at the top of the list as the SPD crashed to their worst result in 20 years | Sean Gallup/Getty Images

For the SPD, the decline began when the German Greens started to peel away “lifestyle liberals” — younger, pacifist and environmentalist voters — in the 1980s. Having lost the organic muesli-eaters, the party went on to alienate beer-and-wurst Sozis. Starting in 2004, many working-class and leftist voters defected to Die Linke in protest of former SPD Chancellor Gerhard Schröder’s neoliberal reforms of labor laws, unemployment benefits and pensions.

Schröder’s Agenda 2010 reforms laid the foundation for Germany’s economic recovery over the last decade, but they hurt many core left-wing voters and fostered a generation of “mini-jobs.” More recently, the SPD’s embrace of multiculturalism and gay marriage cost it some traditional supporters.

“The old working class is disappearing historically, and therefore left-wing parties need to look for other voter groups in the middle classes,” said Colin Crouch, emeritus professor of sociology at Britain’s Warwick University.

After serving as junior partners in governments led by conservative Chancellor Angela Merkel for eight of the last 12 years, the Social Democrats were unable to present themselves as a credible alternative.

If Infratest Dimap’s model is right, nearly 900,000 SPD voters switched on Sunday to the AfD and the FDP. While those two parties have very different economic philosophies, they share a common aversion to Merkel’s decision to welcome more than 1.5 million refugees and other migrants in 2015-2016 and a refusal to help weaker eurozone partners financially.

Portuguese Prime Minister Antonio Costa currently leads a successful left-wing government | Mario Cruz/EPA

As a result, the SPD joins the ranks of other European center-left parties at risk of tearing themselves apart — and possibly losing their souls — over how to win back the voters they lost.

Left behind?

Austria’s Socialist Party has adopted some of the anti-immigration rhetoric of the populist Freedom Party in order to survive. In Britain, Jeremy Corbyn has embraced Brexit and curbing immigration, as well as old-style tax-and-spend and nationalization policies, to try to revive Labour’s fortunes. He is aided by a first-past-the-post electoral system that gives a premium to big parties and punishes fragmentation.

On the Continent, where proportional representation dominates, the risks of a splintering of the left are far greater. In France, far-left leader Jean-Luc Mélenchon is positioning his anti-globalization, Euroskeptic movement as the sole real opposition to Macron’s labor market liberalization, at the risk of driving Socialist reformers into Macron’s arms.

The SPD may win back some lost voters simply by going into opposition and restoring a clearer left-right divide — but the four-way split in defections and the shifting class base of its electorate makes its task ever more complicated.

If the party is to make itself relevant to German workers, it will have to grapple with the changing nature of society and of work, as well as declining unionization and party membership.

“Whichever way the SPD moves, it’s going to lose people on the other side” — Researcher Andrew Watt

The questions the SPD will need to answer include: whether to protect job-for-life incumbents or favor precarious job-creation for the unemployed; how to provide credible social rights for a growing army of gig workers in service industries; how to share the cost of the welfare state in an aging society; and how to reconcile a diverse, tolerant community with a more traditional national identity.

Andrew Watt, a researcher with the German trade unions’ Hans-Böckler Foundation, suggests the left will need two parties that compete against each other but are able to compromise and form coalitions together. He pointed to the success of Portuguese Prime Minister Antonio Costa, who leads a minority Socialist government supported by two smaller communist and leftist parties.

“You have to have two fishing boats. One that tries to get back traditional voters in competition with AfD, Die Linke, Mélenchon and Front National,” he said. “And another party that competes with the CDU and the FDP, or with Macron, for the more comfortably-off working class, professionals, creatives and public sector workers.”

“You can’t say ‘we just have to push left now,’” he added. “Whichever way the SPD moves, it’s going to lose people on the other side.”

German defeat: Workers walk out on Europe’s mainstream left

V-2

[ [ AT/GC ] ]

So Merkel won re-election?

That she did, but as someone already mentioned it was the worst federal election performance for the CDU in 68 years. The rise of the AFD can be successfully stemmed if Merkel gets back to behaving like a CDU politician; in a social context that is. I said it elsewhere that she'd be wise to take a few cues from her Interior Minister and it appears that's what she intends to do. The interesting thing is that they didn't just poach votes from the CDU (over a million), but the SPD, Die Linke, Die Grünen as well, including drawing out an additional 700,000 former non-voters.

Merkel is toast... you think them Germans was cool with here allowing all those refugees in Germany.

It isn't so much the immigrants as it is the bureaucrats, their brand of multiculturalism and the ideas they've got about integration with very little in the way of political - nevermind public - discourse. I could expand on that quite a bit if necessary. Modern day Germany is otherwise an incredibly accepting country and society in which POC would find less discrimination than they do today stateside (with police brutality in particular being a total and complete non-issue). Nobody, or at least very few actually want to see a party like the AFD in a position of governance. It's more of a wake up call to the establishment parties and needs to be taken seriously.

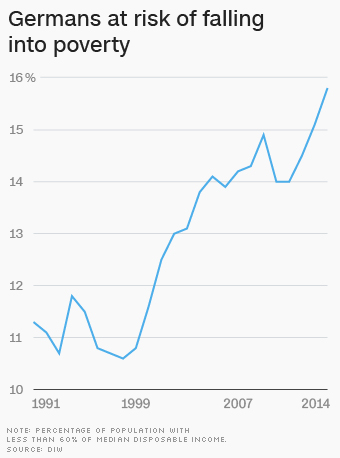

That isn't to say there aren't issues with migrant crime and such that have people legitimately alarmed, but also a non-negotiable €94 billion commitment for refugees through 2020 is an off-putting prospect for many when they are struggling to make end's meet themselves. Overall, the economy is performing at a high level and unemployment is low but that doesn't speak to the increasing level of income equality and it's a phenomenon that's been exacerbated in almost every western nation over the last few decades.

DynamoEAR

All Star

DrBanneker

Space is the Place

Wow so SpD can get even more down and AfD can get more share??

Perhaps!

Germany May Face New Elections After Coalition Talks Fail

Germany May Face New Elections After Coalition Talks Fail

By MELISSA EDDY and KATRIN BENNHOLDNOV. 20, 2017

Chancellor Angela Merkel after meeting with President Frank-Walter Steinmeier of Germany, in Berlin, on Monday. Odd Andersen/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

BERLIN — Chancellor Angela Merkel of Germany faced the greatest crisis of her political career on Monday, after late-night negotiations to form a new government collapsed, raising the prospect of a snap election.

The chancellor expressed a preference for a new election, saying that she was doubtful that a government lacking a majority in Parliament could handle the many challenges it faces.

“I don’t want to say never, but I am very skeptical, and believe that new elections would be the better way forward,” the chancellor told the public broadcaster ARD.

The rapid developments thrust Germany, a bedrock of stability in Europe, into its worst period of political uncertainty since the Cold War.

It also raised new doubts about the political longevity of Ms. Merkel, considered perhaps the West’s most ardent defender of democratic values and freedoms.

“There is no coalition of the willing to form a government,” said Thomas Kleine-Brockhoff, director of the Berlin office of the German Marshall Fund. “This is uncharted territory since 1949. We’re facing a protracted period of political immobility. Not only is this not going to go away soon, there is no clear path out.”

Calling new elections is not a straightforward procedure in Germany. Written with the unstable governments and eventual collapse of the Weimar Republic in mind, the German constitution includes several hurdles that make it difficult to call a snap election.

The breakdown of the talks came against the backdrop of other forces of instability that have been rattling Europe recently, including Britain’s exit from the European Union and a Catalonia secession crisis in Spain.

Ms. Merkel met in private on Monday with President Frank-Walter Steinmeier, who, as head of state, is charged with trying to break the deadlock in coalition talks. He could also appoint a chancellor to lead a minority government. If those actions fail, a new round of elections could also be called.

The potential for instability in Germany would be a major blow to the European Union. Ms. Merkel has been the region’s dominant political figure of the past decade. Her leadership is credited with helping to guide the bloc through the 2008 financial crisis and, more recently, with providing a powerful counterpoint to populists across the Continent and beyond.

Financial markets reacted calmly to the turmoil in Berlin, calculating that the German economy could power through the uncertainty. After opening lower, the DAX index of major stocks closed the day higher. The euro fell slightly.

But some economists warned that the longer term effects could be more severe. A weak government might be unable to agree on needed improvements to infrastructure and the education system, for example.

“The economic situation is very good,” Christoph M. Schmidt, chairman of the German Council of Economic Experts, said in a statement. “But over the mid and long term there are big challenges, especially the demographic shift, digitalization, sensible development of the European Union, and climate change.”

The political instability stems from the elections in Germany on Sept. 24, when Ms. Merkel’s Christian Democrats finished first. But their share of the overall vote dropped significantly, while the far-right Alternative for Germany party scored a record vote, entering Parliament for the first time as the third-biggest grouping.

Even so, political analysts had expected Ms. Merkel to form a new coalition government that would have allowed her to remain as chancellor. That may still happen, but it will be harder now, and it is unlikely to happen soon, experts say.

“Building a government is always a difficult process,” Mr. Steinmeier said on Monday, reminding lawmakers of their duty to serve the people who voted them into office. “I expect from all a readiness to talk to make agreeing a government possible in the near future,” he added.

Elsewhere in Europe, the possibility of a weakened Ms. Merkel and of an inward-looking Germany alarmed some leaders. The chancellor canceled a meeting in Berlin with Prime Minister Mark Rutte of the Netherlands. In Paris, President Emmanuel Macron of France said that Ms. Merkel’s difficulties were a serious hurdle to the partnership between their two countries.

France has “no interest in a worsening of the situation” in Germany, Mr. Macron said in a statement on Monday. “Our wish is that our main partner, for the sake of Germany and Europe, remains strong and stable, so that we can move forward together,” he added.

Even if Ms. Merkel’s problems leave Mr. Macron as Europe’s de facto strongest leader — with weak domestic opposition in France, a strengthening economy, and a good record so far on driving through economic overhauls — the French president had been counting on Ms. Merkel as an ally in his push to make changes to the European Union.

Mr. Macron will be aware that his agenda for the bloc, which includes a common defense force, a strengthened euro, and a joint finance minister, stands no chance without German backing. He already seemed to have established a strong rapport with Ms. Merkel. The leaders have met frequently since Mr. Macron’s election; for the past six months, the French news media has been full of images of the two of them smiling side by side.

Ms. Merkel had originally set Friday as the deadline for reaching an agreement with the Free Democrats, the Greens, and the Christian Social Union, which forms a conservative bloc with the chancellor’s Christian Democrats. From the outset, all of those parties had differed markedly on key issues, notably migration and climate policies, resulting in strained talks that led to open sniping between some participants.

After they agreed to take talks into overtime, negotiators and party leaders failed to produce any breakthroughs over the weekend, and the Free Democrats quit the talks.

Ms. Merkel could try to approach the Social Democrats about forming a coalition. But the center-left party has served as the junior coalition partner to the Christian Democrats since 2013 and on Monday, the party’s leader, Martin Schulz, said his group had no interest in another round.

Should Mr. Steinmeier decide to nominate a chancellor, it would most likely be Ms. Merkel, given that her party has the largest bloc in Parliament. She would then need to be confirmed by lawmakers, but would be left with a minority government. But such a constellation would require she continually seek alliances with other partners, robbing Germans of the governmental stability they have known since the end of World War II.

Despite the difficulties presented by the possible solutions, experts said calling a snap election would be a last resort.

Germany May Face New Elections After Coalition Talks Fail

By MELISSA EDDY and KATRIN BENNHOLDNOV. 20, 2017

Chancellor Angela Merkel after meeting with President Frank-Walter Steinmeier of Germany, in Berlin, on Monday. Odd Andersen/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

BERLIN — Chancellor Angela Merkel of Germany faced the greatest crisis of her political career on Monday, after late-night negotiations to form a new government collapsed, raising the prospect of a snap election.

The chancellor expressed a preference for a new election, saying that she was doubtful that a government lacking a majority in Parliament could handle the many challenges it faces.

“I don’t want to say never, but I am very skeptical, and believe that new elections would be the better way forward,” the chancellor told the public broadcaster ARD.

The rapid developments thrust Germany, a bedrock of stability in Europe, into its worst period of political uncertainty since the Cold War.

It also raised new doubts about the political longevity of Ms. Merkel, considered perhaps the West’s most ardent defender of democratic values and freedoms.

“There is no coalition of the willing to form a government,” said Thomas Kleine-Brockhoff, director of the Berlin office of the German Marshall Fund. “This is uncharted territory since 1949. We’re facing a protracted period of political immobility. Not only is this not going to go away soon, there is no clear path out.”

Calling new elections is not a straightforward procedure in Germany. Written with the unstable governments and eventual collapse of the Weimar Republic in mind, the German constitution includes several hurdles that make it difficult to call a snap election.

The breakdown of the talks came against the backdrop of other forces of instability that have been rattling Europe recently, including Britain’s exit from the European Union and a Catalonia secession crisis in Spain.

Ms. Merkel met in private on Monday with President Frank-Walter Steinmeier, who, as head of state, is charged with trying to break the deadlock in coalition talks. He could also appoint a chancellor to lead a minority government. If those actions fail, a new round of elections could also be called.

The potential for instability in Germany would be a major blow to the European Union. Ms. Merkel has been the region’s dominant political figure of the past decade. Her leadership is credited with helping to guide the bloc through the 2008 financial crisis and, more recently, with providing a powerful counterpoint to populists across the Continent and beyond.

Financial markets reacted calmly to the turmoil in Berlin, calculating that the German economy could power through the uncertainty. After opening lower, the DAX index of major stocks closed the day higher. The euro fell slightly.

But some economists warned that the longer term effects could be more severe. A weak government might be unable to agree on needed improvements to infrastructure and the education system, for example.

“The economic situation is very good,” Christoph M. Schmidt, chairman of the German Council of Economic Experts, said in a statement. “But over the mid and long term there are big challenges, especially the demographic shift, digitalization, sensible development of the European Union, and climate change.”

The political instability stems from the elections in Germany on Sept. 24, when Ms. Merkel’s Christian Democrats finished first. But their share of the overall vote dropped significantly, while the far-right Alternative for Germany party scored a record vote, entering Parliament for the first time as the third-biggest grouping.

Even so, political analysts had expected Ms. Merkel to form a new coalition government that would have allowed her to remain as chancellor. That may still happen, but it will be harder now, and it is unlikely to happen soon, experts say.

“Building a government is always a difficult process,” Mr. Steinmeier said on Monday, reminding lawmakers of their duty to serve the people who voted them into office. “I expect from all a readiness to talk to make agreeing a government possible in the near future,” he added.

Elsewhere in Europe, the possibility of a weakened Ms. Merkel and of an inward-looking Germany alarmed some leaders. The chancellor canceled a meeting in Berlin with Prime Minister Mark Rutte of the Netherlands. In Paris, President Emmanuel Macron of France said that Ms. Merkel’s difficulties were a serious hurdle to the partnership between their two countries.

France has “no interest in a worsening of the situation” in Germany, Mr. Macron said in a statement on Monday. “Our wish is that our main partner, for the sake of Germany and Europe, remains strong and stable, so that we can move forward together,” he added.

Even if Ms. Merkel’s problems leave Mr. Macron as Europe’s de facto strongest leader — with weak domestic opposition in France, a strengthening economy, and a good record so far on driving through economic overhauls — the French president had been counting on Ms. Merkel as an ally in his push to make changes to the European Union.

Mr. Macron will be aware that his agenda for the bloc, which includes a common defense force, a strengthened euro, and a joint finance minister, stands no chance without German backing. He already seemed to have established a strong rapport with Ms. Merkel. The leaders have met frequently since Mr. Macron’s election; for the past six months, the French news media has been full of images of the two of them smiling side by side.

Ms. Merkel had originally set Friday as the deadline for reaching an agreement with the Free Democrats, the Greens, and the Christian Social Union, which forms a conservative bloc with the chancellor’s Christian Democrats. From the outset, all of those parties had differed markedly on key issues, notably migration and climate policies, resulting in strained talks that led to open sniping between some participants.

After they agreed to take talks into overtime, negotiators and party leaders failed to produce any breakthroughs over the weekend, and the Free Democrats quit the talks.

Ms. Merkel could try to approach the Social Democrats about forming a coalition. But the center-left party has served as the junior coalition partner to the Christian Democrats since 2013 and on Monday, the party’s leader, Martin Schulz, said his group had no interest in another round.

Should Mr. Steinmeier decide to nominate a chancellor, it would most likely be Ms. Merkel, given that her party has the largest bloc in Parliament. She would then need to be confirmed by lawmakers, but would be left with a minority government. But such a constellation would require she continually seek alliances with other partners, robbing Germans of the governmental stability they have known since the end of World War II.

Despite the difficulties presented by the possible solutions, experts said calling a snap election would be a last resort.