You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Disputed 1619 project was CORRECT, Slavery WAS key to US Revolution; Gerald Horne proved in 2014

- Thread starter ☑︎#VoteDemocrat

- Start date

More options

Who Replied?The 1619 Project and the Work of the Historian

earlyamericanists.com

The 1619 Project and the Work of the Historian

By Joseph M. Adelman

7-8 minutes

Yesterday Princeton historian Sean Wilentz published his latest piece opposing the 1619 Project at The Atlantic. In it, Wilentz argues that he—along with the other historians who signed a letter to the editors of the New York Times Magazine questioning the Project’s conclusions—are taking issue as a “matter of facts” that were presented in the 1619 Project, in particular in the essay authored by Nikole Hannah-Jones, the lead editor for the magazine’s issue, and in the letter of response from the Magazine’s editor, Jack Silverstein.

I’d initially planned not to comment publicly on the 1619 Project, but Wilentz’s essay is flawed in the precise area of my expertise—Revolutionary-era newspapers—in ways that diminish the credence of his claims. Critiques of the 1619 Project have tended to obscure the practice of historical research and writing, but there is nonetheless an opportunity to illuminate how we locate, contextualize, and interrogate sources. In making that clear, we can understand better the debate about interpretations of the American Revolution.

In the Atlantic essay, Wilentz focuses on the Somerset case, the 1772 decision in which an enslaved man was freed because, judge Lord Mansfield determined, his master could not legally hold him in bondage in England. Here’s what he writes about how American newspapers responded:

There’s a lot going on here. The information Wilentz provided was so precise that it had me wondering at its source. The only scholar he refers to in the essay is Christopher L. Brown, so I went back to Brown’s Moral Capital and the sections he wrote about the Somerset case. There was no reference to newspaper coverage, but Brown in turn cites journalism scholar Patricia Bradley, who published Slavery, Propaganda, and the American Revolution in 1998. Her book includes an entire chapter on the Somerset decision and its coverage in the American colonies, but not the numbers that Wilentz cited. For that, it seems we need to go back to a 1984 paper that Bradley presented at the annual meeting of the Association for Education in Journalism—or at least, this is the only place I could locate these figures. I’d also mention that Bradley’s 1984 paper seems the most likely source because she includes the very specific anecdote about Princess Caroline in her essay.

But between my own knowledge and Bradley’s paper and chapter, it is clear that Wilentz’s statistics are misleading.

First, there are two problems with the number of newspapers he cites. Bradley’s research involved taking a sample of newspapers, and she did not include newspapers from North Carolina or Georgia because too few issues existed. So we’re missing two colonies which boasted three newspapers (two in North Carolina and one in Georgia).[1] The other problem is that those six newspapers are the sum total of those published in those colonies in 1772. In other words, we could easily re-phrase his first sentence to say that “every newspaper in Maryland, Virginia, and South Carolina reported on the Somerset decision,” which makes the evidence seem far more significant than Wilentz would allow.

Second, as to the number of times the case was mentioned, the significance of the number fifteen isn’t clear. Fifteen mentions doesn’t suggest complete ignorance of the case, but it’s not clear from Bradley’s paper or book chapter how exactly she defined a “mention.” She includes some fascinating information about the extent of coverage in Boston’s Loyalist newspaper, the Massachusetts Gazette … but that’s a complex issue that would require a separate post for a full discussion.

The third issue in Wilentz’s paragraph is his dismissal of the news items about Somerset as appearing in the middle of the newspaper in a “tiny-font.” It sounds clever but does not reflect how newspapers were organized in the eighteenth century. Any mention of the case appeared where it did (on pages 2 and 3) because that was the obvious place to put it. Newspapers were not organized by the importance of the news (with a few notable exceptions). Instead editors organized the paragraphs they collected by function and geography. Long essays and some advertising would appear on the first page, followed by news from London and Europe continuing onto the second page. Then printers would include news from other colonies, usually working their way closer to their own town’s news at the end of page 2 or somewhere on page 3. The rest of the newspaper would then include advertising. News was published by paragraphs with no headlines; the only way to determine what news was important was to read all of it.[2]

Understanding the circulation of news about the case in this way undercuts Wilentz’s claim. It’s actually rather significant that every newspaper published (and available!) in the Southern colonies in 1772 mentioned Somerset, even if only in passing. Further, it’s important to remember that newspapers were less central to the news culture of Southern colonies than they were further north. Elite Southerners did little to support local newspapers, but they would have had access to news about the decision from London newspapers and magazines which, as Bradley and Brown note, reported extensively on the trial and decision. They also would have had access to news through their correspondents in London because letters were a key source of news traveling across the Atlantic. This is not a specific event I’ve researched, to be fair, but my point is that there is very likely more to the story than these newspapers can tell.

Facts are important, but they need to be placed into a historical context. Indeed, the ways in which Wilentz frames newspaper coverage belies just how much the debate over the 1619 Project is actually about interpretations and not, as he claims, simply a “matter of facts.”

_______

[1] The America’s Historical Newspapers database still includes no issues of the Georgia Gazette, the Cape-Fear Mercury, or the North-Carolina Gazette for 1772.

[2] Self-promotion alert! The introduction to my book, Revolutionary Networks, goes into even more detail about how newspapers were structured and edited.

earlyamericanists.com

The 1619 Project and the Work of the Historian

By Joseph M. Adelman

7-8 minutes

Yesterday Princeton historian Sean Wilentz published his latest piece opposing the 1619 Project at The Atlantic. In it, Wilentz argues that he—along with the other historians who signed a letter to the editors of the New York Times Magazine questioning the Project’s conclusions—are taking issue as a “matter of facts” that were presented in the 1619 Project, in particular in the essay authored by Nikole Hannah-Jones, the lead editor for the magazine’s issue, and in the letter of response from the Magazine’s editor, Jack Silverstein.

I’d initially planned not to comment publicly on the 1619 Project, but Wilentz’s essay is flawed in the precise area of my expertise—Revolutionary-era newspapers—in ways that diminish the credence of his claims. Critiques of the 1619 Project have tended to obscure the practice of historical research and writing, but there is nonetheless an opportunity to illuminate how we locate, contextualize, and interrogate sources. In making that clear, we can understand better the debate about interpretations of the American Revolution.

In the Atlantic essay, Wilentz focuses on the Somerset case, the 1772 decision in which an enslaved man was freed because, judge Lord Mansfield determined, his master could not legally hold him in bondage in England. Here’s what he writes about how American newspapers responded:

In the entire slaveholding South, a total of six newspapers—one in Maryland, two in Virginia, and three in South Carolina—published only 15 reports about Somerset, virtually all of them very brief. Coverage was spotty: The two South Carolina newspapers that devoted the most space to the case didn’t even report its outcome. American newspaper readers learned far more about the doings of the queen of Denmark, George III’s sister Caroline, whom Danish rebels had charged with having an affair with the court physician and plotting the death of her husband. A pair of Boston newspapers gave the Somerset decision prominent play; otherwise, most of the coverage appeared in the tiny-font foreign dispatches placed on the second or third page of a four- to six-page issue.

There’s a lot going on here. The information Wilentz provided was so precise that it had me wondering at its source. The only scholar he refers to in the essay is Christopher L. Brown, so I went back to Brown’s Moral Capital and the sections he wrote about the Somerset case. There was no reference to newspaper coverage, but Brown in turn cites journalism scholar Patricia Bradley, who published Slavery, Propaganda, and the American Revolution in 1998. Her book includes an entire chapter on the Somerset decision and its coverage in the American colonies, but not the numbers that Wilentz cited. For that, it seems we need to go back to a 1984 paper that Bradley presented at the annual meeting of the Association for Education in Journalism—or at least, this is the only place I could locate these figures. I’d also mention that Bradley’s 1984 paper seems the most likely source because she includes the very specific anecdote about Princess Caroline in her essay.

But between my own knowledge and Bradley’s paper and chapter, it is clear that Wilentz’s statistics are misleading.

First, there are two problems with the number of newspapers he cites. Bradley’s research involved taking a sample of newspapers, and she did not include newspapers from North Carolina or Georgia because too few issues existed. So we’re missing two colonies which boasted three newspapers (two in North Carolina and one in Georgia).[1] The other problem is that those six newspapers are the sum total of those published in those colonies in 1772. In other words, we could easily re-phrase his first sentence to say that “every newspaper in Maryland, Virginia, and South Carolina reported on the Somerset decision,” which makes the evidence seem far more significant than Wilentz would allow.

Second, as to the number of times the case was mentioned, the significance of the number fifteen isn’t clear. Fifteen mentions doesn’t suggest complete ignorance of the case, but it’s not clear from Bradley’s paper or book chapter how exactly she defined a “mention.” She includes some fascinating information about the extent of coverage in Boston’s Loyalist newspaper, the Massachusetts Gazette … but that’s a complex issue that would require a separate post for a full discussion.

The third issue in Wilentz’s paragraph is his dismissal of the news items about Somerset as appearing in the middle of the newspaper in a “tiny-font.” It sounds clever but does not reflect how newspapers were organized in the eighteenth century. Any mention of the case appeared where it did (on pages 2 and 3) because that was the obvious place to put it. Newspapers were not organized by the importance of the news (with a few notable exceptions). Instead editors organized the paragraphs they collected by function and geography. Long essays and some advertising would appear on the first page, followed by news from London and Europe continuing onto the second page. Then printers would include news from other colonies, usually working their way closer to their own town’s news at the end of page 2 or somewhere on page 3. The rest of the newspaper would then include advertising. News was published by paragraphs with no headlines; the only way to determine what news was important was to read all of it.[2]

Understanding the circulation of news about the case in this way undercuts Wilentz’s claim. It’s actually rather significant that every newspaper published (and available!) in the Southern colonies in 1772 mentioned Somerset, even if only in passing. Further, it’s important to remember that newspapers were less central to the news culture of Southern colonies than they were further north. Elite Southerners did little to support local newspapers, but they would have had access to news about the decision from London newspapers and magazines which, as Bradley and Brown note, reported extensively on the trial and decision. They also would have had access to news through their correspondents in London because letters were a key source of news traveling across the Atlantic. This is not a specific event I’ve researched, to be fair, but my point is that there is very likely more to the story than these newspapers can tell.

Facts are important, but they need to be placed into a historical context. Indeed, the ways in which Wilentz frames newspaper coverage belies just how much the debate over the 1619 Project is actually about interpretations and not, as he claims, simply a “matter of facts.”

_______

[1] The America’s Historical Newspapers database still includes no issues of the Georgia Gazette, the Cape-Fear Mercury, or the North-Carolina Gazette for 1772.

[2] Self-promotion alert! The introduction to my book, Revolutionary Networks, goes into even more detail about how newspapers were structured and edited.

poynter.org

It's Banned Books Week in America. In some places, the '1619 Project' is being targeted. - Poynter

By: Tom Jones

2-3 minutes

This is “Banned Books Week” in America.

It’s described as the “annual event celebrating the freedom to read. Banned Books Week was launched in 1982 in response to a sudden surge in the number of challenges to books in schools, bookstores and libraries. Typically held during the last week of September, it highlights the value of free and open access to information. Banned Books Week brings together the entire book community — librarians, booksellers, publishers, journalists, teachers, and readers of all types — in shared support of the freedom to seek and to express ideas, even those some consider unorthodox or unpopular.”

Appearing on CNN’s “Reliable Sources,” Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter Nikole Hannah-Jones talked about her “1619 Project” for The New York Times Magazine.

“This is a particularly dangerous moment,’’ Hannah-Jones told host Brian Stelter. “It’s one thing to have right-wing media saying they don’t like the ‘1619 Project,’ they don’t agree with the ‘1619 Project.’ But it’s quite something else to have politicians from state legislatures down to school boards actually making prohibitions against teaching a work of American journalism or really any of these other texts. The fact that we are all talking about this fake controversy called ‘critical race theory’ really speaks to how successful the public propaganda campaign has been. I don’t think it’s just about scared white parents. It’s about politicians savvily stoking racial resentment in response, I think, to the global protests last year in order to divide America from each other, and they’re being quite successful.”

Hannah-Jones said it isn’t just the “1619 Project” that is being targeted.

“This is actually trying to control the collective memory of this country,” Hannah-Jones said. “And trying to say we just want to purge uncomfortable truths from our collective memory. And that’s very dangerous.”

This article originally appeared in Covering COVID-19, a daily Poynter briefing of story ideas about the coronavirus and other timely topics for journalists. Sign up here to have it delivered to your inbox every weekday morning.

Eric Williams and the Tangled History of Capitalism and Slavery

The Politician-Scholar

Eric Williams and the tangled history of capitalism and slavery.

By Gerald Horne

TODAY 5:00 AM

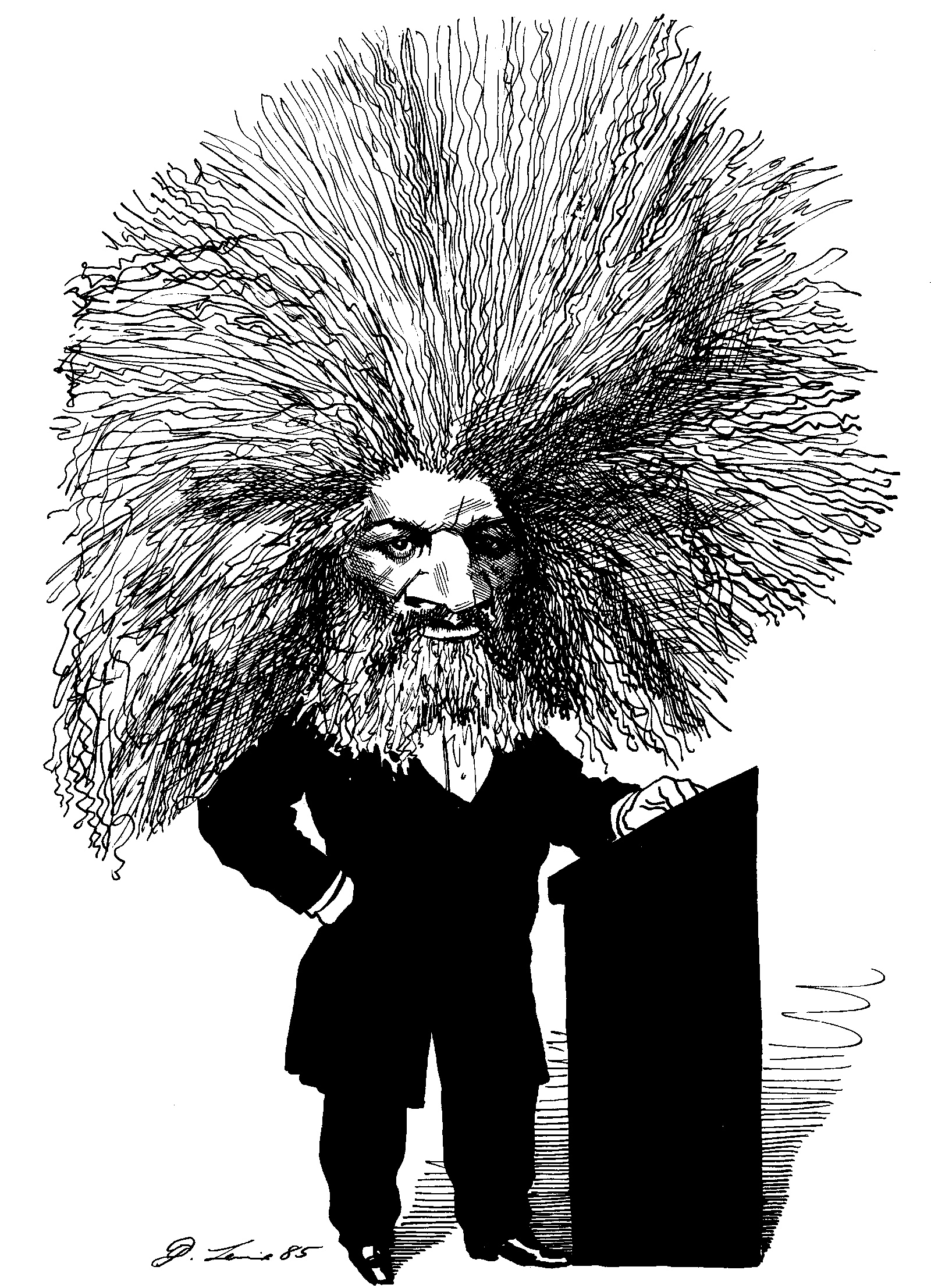

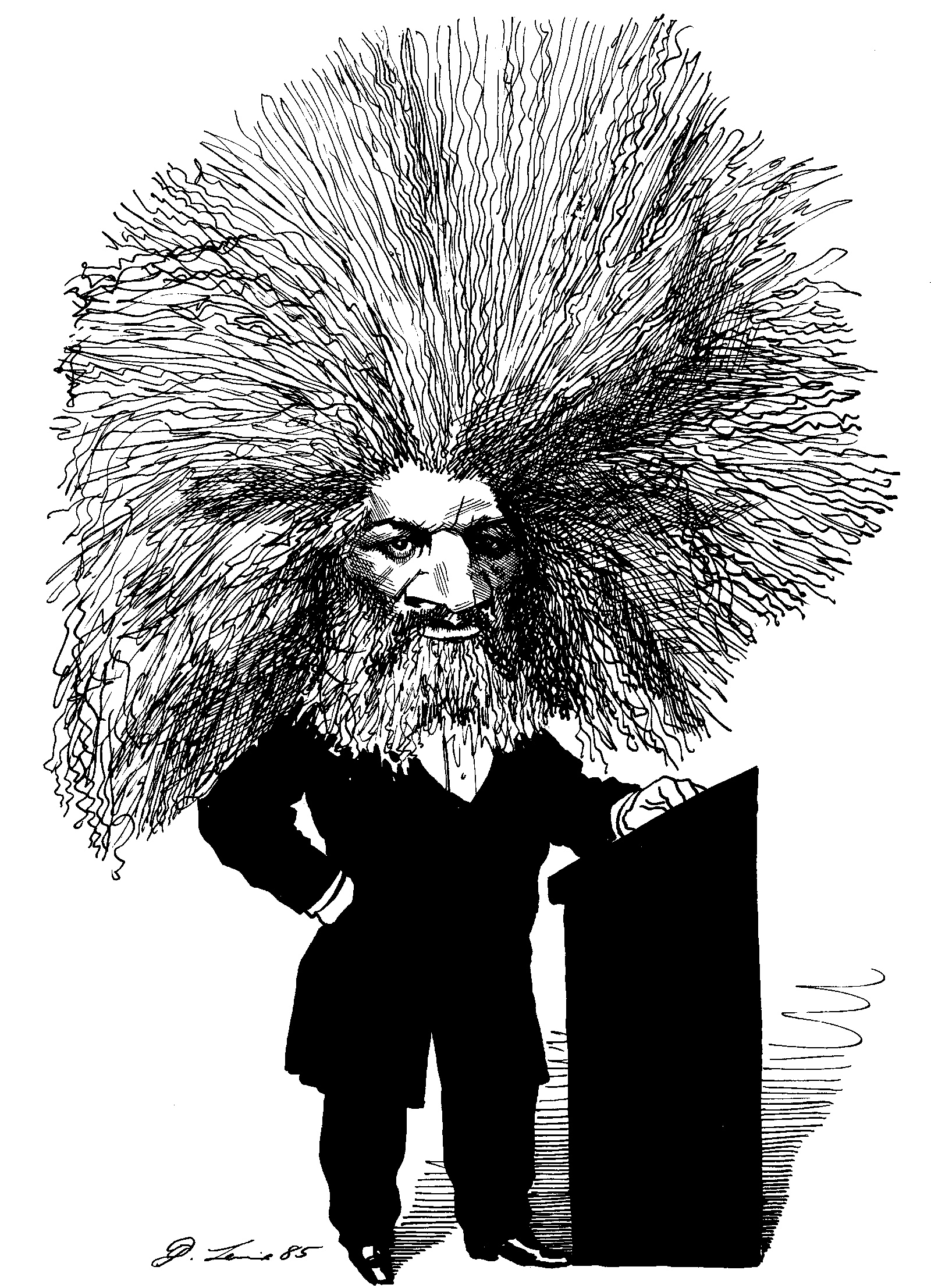

Illustration by Joe Ciardiello.

Before he became a celebrated author and the founding father and first prime minister of Trinidad and Tobago, Eric Eustace Williams was an adroit footballer. At his high school, Queen’s Royal College, he was a fierce competitor, which likely led to an injury that left him deaf in his right ear. Yet as Williams’s profile as a scholar and national leader rose, so did the attempts by his critics to turn his athleticism against him. An “expert dribbler” known for prancing downfield with the ball kissing one foot, then the other, Williams was now accused by his political detractors of not being a team player. Driven by his desire to play to the gallery—or so it was said—he proved to be uninterested in whether his team (or his nation, not to mention the erstwhile British Commonwealth) was victorious.

What his critics described as a weakness, though, was also a strength: His willingness to go it alone on the field probably contributed to his willingness to break from the historiographic pack during his tenure at Oxford University, and it also led him to chart his own political course. Williams, after all, often had good reason not to trust his political teammates, particularly those with close ties to London. Moreover, he was convinced that a good politician should play to the gallery: Ultimately, he was a public representative. And this single-minded determination to score even if it meant circumventing his teammates, instilled in him a critical mindset, one that helped define both his scholarship—in particular his groundbreaking Capitalism and Slavery—and his work as a politician and an intellectual, though admittedly this trait proved to be more effective at Oxford and Howard University than during his political career, which coincided with the bruising battles of the Cold War.

A new edition of Capitalism and Slavery, published by the University of North Carolina Press with a foreword by the economist William Darity, reminds us in particular of Williams’s independent political and intellectual spirit and how his scholarship upended the historiographical consensus on slavery and abolition. Above all else, in this relatively slender volume, Williams asserted the primacy of the enslaved themselves in breaking the chains that bound them, putting their experiences at the center of his research. Controversially, he also placed slavery at the heart of the rise of capitalism and the British Empire, which carried profound implications for its successor, the United States. The same holds true for his devaluation of the humanitarianism of white abolitionists and their allies as a spur for ending slavery. In many ways, the book augured his determination as a political actor as well: Williams the academic striker sped downfield far ahead of the rest and scored an impressive goal for the oppressed while irking opponents and would-be teammates alike. But his subsequent career as a politician also came as a surprise: Despite his own radical commitments as a historian, as a politician Williams broke in significant ways from many of his anti-colonial peers. For both reasons of his own making and reasons related to leading a small island nation in the United States’ self-proclaimed backyard, Williams as prime minister was hardly seen as an avatar of radicalism.

Eric Williams was born in 1911 in Port-of-Spain, the capital of Trinidad and Tobago, then a financially depressed British colony. His father was far from wealthy, receiving only a primary education before becoming a civil service clerk at the tender age of 17. In his affecting autobiography, Williams describes his mother’s “contribution to the family budget” by baking “bread and cakes” for sale. She was a descendant of an old French Creole family, with the lighter skin hue to prove it.

Despite his humble origins, the studious and disciplined Williams won a prized academic scholarship at the age of 11, putting him on track to become a “coloured Englishman,” he noted ruefully. His arrival at Oxford in 1931—again on a scholarship—seemingly confirmed this future. There he mingled in a progressive milieu that included the founder of modern Kenya, Jomo Kenyatta, and the self-exiled African American socialist Paul Robeson. It was at Oxford that Williams wrote “The Economic Aspect of the Abolition of the West Indian Slave Trade and Slavery,” which was later transformed into the book at hand. In both works, but in the book more decisively, Williams punctured the then-reigning notion that abolitionism had been driven by humanitarianism—an idea that conveniently kept Europeans and Euro-Americans at the core of this epochal development. Instead Williams stressed African agency and resistance, which in turn drove London’s financial calculations. He accomplished this monumental task in less than 200 pages of text, making the response that followed even more noteworthy. Extraordinarily, entire volumes have been devoted to weighing his conclusions in this one book.

It would not be an exaggeration, then, to say that when Williams published Capitalism and Slavery in 1944, it ignited a firestorm of applause and fury alike. His late biographer, Colin Palmer, observed that “reviewers of African descent uniformly praised the work, while those who claimed European heritage were much less enthusiastic and more divided in their reception.” One well-known scholar of the latter persuasion assailed the “Negro nationalism” that Williams espoused in it. Nonetheless, Capitalism and Slavery has become arguably the most academically influential work on slavery written to date. It has sold tens of thousands of copies—with no end in sight—and has been translated into numerous European languages as well as Japanese and Korean. The book continues to inform debates on the extent to which capitalism was shaped by the enslavement of Africans, not to mention the extent to which these enslaved workers struck the first—and most decisive—blow against their inhumane bondage.

Proceeding chronologically from 1492 to the eve of the US Civil War, Williams grounded his narrative in parliamentary debates, merchants’ papers, documents from Whitehall, memoirs, and abolitionist renderings, recording the actions of the oppressed as they were reflected in these primary sources. The book has three central theses that have captured the attention of generations of readers and historians. The first was Williams’s almost offhand assertion that slavery had produced racism, not vice versa: “Slavery was not born of racism,” he contended, but “rather, racism was the consequence of slavery.” To begin with, “unfree labor in the New World was brown, white, black and yellow; Catholic, Protestant and pagan,” with various circumstances combining to promote the use of enslaved African labor. For example, “escape was easy for the white servant; less easy for the Negro,” who was “conspicuous by his color and features”—and, Williams added, “the Negro slave was cheaper.” But it was in North America most dramatically that slavery became encoded with “race” and thus, through its contorted rationalizations, ended up producing a new culture of racism.

This thesis was provocative for several reasons, but perhaps most of all because it implied that once the material roots of slavery had been ripped up, the modern world would finally witness the progressive erosion of anti-Black politics and culture. This optimistic view was echoed by the late Howard University classicist Frank Snowden in his trailblazing book Before Color Prejudice: The Ancient View of Blacks. Of course, sterner critics could well contend that such optimism was misplaced, that it misjudged the extent to which many post-slavery societies had been poisoned at the root. But this sunnier view of post-slavery societies was spawned in part by the proliferation of anti-colonial and anti–Jim Crow activism in the 1940s and ’50s.

Williams’s second thesis hasn’t stirred as much controversy, but it also exerted an enormous influence on the scholarship to come: He insisted that slavery fueled British industrial development, and therefore that slavery was the foundation not only of British capitalism but of capitalism as a whole. To prove this claim, Williams cited the many British mercantilists who themselves knew that slavery and the slave trade (not to mention the transportation of settlers) relied on a complex economic system, one that included shipbuilding and shackles to restrain the enslaved, along with firearms, textiles, and rum—manufacturing, in short. Sugar and tobacco, then cotton, were ferociously profitable, adding mightily to London’s coffers, which meant more ships and firearms, in a circle devoid of virtue. Assuredly, the immense wealth generated by slavery and the slave trade—the latter, at times, bringing a 1,700 percent profit—provided rocket fuel to boost the takeoff of capitalism itself.

If Williams’s first thesis has been critiqued by subsequent historians and scholars, who have found its apparent optimism about the ability to uproot racism misguided, his second has been largely embraced and bolstered by subsequent scholars, including Walter Rodney in How Europe Underdeveloped Africa and Joseph Inikori in Africans and the Industrial Revolution in England.

The latter, in fact, goes farther than Williams does. Inikori argues that before the advent of the slave trade, England’s West Yorkshire, the West Midlands, and South Lancashire were poorer regions; but buoyed by slavery’s economic stimulus, they became wealthy and industrialized. Similarly, in the period from 1650 to 1850, the Americas were effectively an extension of Africa itself in terms of exports, buoying the former to the detriment of the latter. More polemically, Rodney portrays Africa and Europe on a veritable seesaw, with one declining as the other rises, the two processes intrinsically united in a manner that echoes Williams.

The scholarship that followed Williams’s book also pointed to something that Williams missed in his account of the entwined nature of capitalism and slavery: The intense feudal religiosity that characterized Spain, Protestant England’s inquisitorial Catholic foe, began to yield in favor of a similarly intense racism—albeit shaped and formed by religion, just as racial slavery shaped and formed capitalism. As the historian Donald Matthews suggested in his book At the Altar of Lynching, this ultimate Jim Crow expression of hate—often featuring the immolation of the cross, if not of the victimized himself—was also a kind of religious sacrament as well as a holdover from a previous epoch in England’s history, in which Queen Mary I (also known as “Bloody Mary”) burned Protestant foes at the stake during her tumultuous and brief 16th-century reign. In the bumpy transition from feudalism to capitalism, there is a perverse devolutionary logic embedded in the shift from torching presumed heretics to torching actual Africans.

Nonetheless, Williams’s most disputed thesis was his downgrading of the heroic role of the British abolitionists. In his telling of their story, he argued that naked economic self-interest, more than morality or humanitarianism, drove England’s retreat from the slave trade in 1807 and its barring of slavery in 1833. Like The New York Times’ 1619 Project, this part of Williams’s argument pricked a sensitive nerve in the nation’s self-conception. In 2007, on the 200th anniversary of the official banning of human trafficking from Africa, the British prime minister and the monarch presided over a commemoration that sought to foreground Britain’s abolitionism, not its central role in the muck of slavery’s repulsiveness. Instead of focusing on the United Kingdom as a primary beneficiary of the enslavement of Africans, they refashioned their once formidable empire as the very embodiment of abolitionism.

The Politician-Scholar

Eric Williams and the tangled history of capitalism and slavery.

By Gerald Horne

TODAY 5:00 AM

Illustration by Joe Ciardiello.

Before he became a celebrated author and the founding father and first prime minister of Trinidad and Tobago, Eric Eustace Williams was an adroit footballer. At his high school, Queen’s Royal College, he was a fierce competitor, which likely led to an injury that left him deaf in his right ear. Yet as Williams’s profile as a scholar and national leader rose, so did the attempts by his critics to turn his athleticism against him. An “expert dribbler” known for prancing downfield with the ball kissing one foot, then the other, Williams was now accused by his political detractors of not being a team player. Driven by his desire to play to the gallery—or so it was said—he proved to be uninterested in whether his team (or his nation, not to mention the erstwhile British Commonwealth) was victorious.

What his critics described as a weakness, though, was also a strength: His willingness to go it alone on the field probably contributed to his willingness to break from the historiographic pack during his tenure at Oxford University, and it also led him to chart his own political course. Williams, after all, often had good reason not to trust his political teammates, particularly those with close ties to London. Moreover, he was convinced that a good politician should play to the gallery: Ultimately, he was a public representative. And this single-minded determination to score even if it meant circumventing his teammates, instilled in him a critical mindset, one that helped define both his scholarship—in particular his groundbreaking Capitalism and Slavery—and his work as a politician and an intellectual, though admittedly this trait proved to be more effective at Oxford and Howard University than during his political career, which coincided with the bruising battles of the Cold War.

A new edition of Capitalism and Slavery, published by the University of North Carolina Press with a foreword by the economist William Darity, reminds us in particular of Williams’s independent political and intellectual spirit and how his scholarship upended the historiographical consensus on slavery and abolition. Above all else, in this relatively slender volume, Williams asserted the primacy of the enslaved themselves in breaking the chains that bound them, putting their experiences at the center of his research. Controversially, he also placed slavery at the heart of the rise of capitalism and the British Empire, which carried profound implications for its successor, the United States. The same holds true for his devaluation of the humanitarianism of white abolitionists and their allies as a spur for ending slavery. In many ways, the book augured his determination as a political actor as well: Williams the academic striker sped downfield far ahead of the rest and scored an impressive goal for the oppressed while irking opponents and would-be teammates alike. But his subsequent career as a politician also came as a surprise: Despite his own radical commitments as a historian, as a politician Williams broke in significant ways from many of his anti-colonial peers. For both reasons of his own making and reasons related to leading a small island nation in the United States’ self-proclaimed backyard, Williams as prime minister was hardly seen as an avatar of radicalism.

Eric Williams was born in 1911 in Port-of-Spain, the capital of Trinidad and Tobago, then a financially depressed British colony. His father was far from wealthy, receiving only a primary education before becoming a civil service clerk at the tender age of 17. In his affecting autobiography, Williams describes his mother’s “contribution to the family budget” by baking “bread and cakes” for sale. She was a descendant of an old French Creole family, with the lighter skin hue to prove it.

Despite his humble origins, the studious and disciplined Williams won a prized academic scholarship at the age of 11, putting him on track to become a “coloured Englishman,” he noted ruefully. His arrival at Oxford in 1931—again on a scholarship—seemingly confirmed this future. There he mingled in a progressive milieu that included the founder of modern Kenya, Jomo Kenyatta, and the self-exiled African American socialist Paul Robeson. It was at Oxford that Williams wrote “The Economic Aspect of the Abolition of the West Indian Slave Trade and Slavery,” which was later transformed into the book at hand. In both works, but in the book more decisively, Williams punctured the then-reigning notion that abolitionism had been driven by humanitarianism—an idea that conveniently kept Europeans and Euro-Americans at the core of this epochal development. Instead Williams stressed African agency and resistance, which in turn drove London’s financial calculations. He accomplished this monumental task in less than 200 pages of text, making the response that followed even more noteworthy. Extraordinarily, entire volumes have been devoted to weighing his conclusions in this one book.

It would not be an exaggeration, then, to say that when Williams published Capitalism and Slavery in 1944, it ignited a firestorm of applause and fury alike. His late biographer, Colin Palmer, observed that “reviewers of African descent uniformly praised the work, while those who claimed European heritage were much less enthusiastic and more divided in their reception.” One well-known scholar of the latter persuasion assailed the “Negro nationalism” that Williams espoused in it. Nonetheless, Capitalism and Slavery has become arguably the most academically influential work on slavery written to date. It has sold tens of thousands of copies—with no end in sight—and has been translated into numerous European languages as well as Japanese and Korean. The book continues to inform debates on the extent to which capitalism was shaped by the enslavement of Africans, not to mention the extent to which these enslaved workers struck the first—and most decisive—blow against their inhumane bondage.

Proceeding chronologically from 1492 to the eve of the US Civil War, Williams grounded his narrative in parliamentary debates, merchants’ papers, documents from Whitehall, memoirs, and abolitionist renderings, recording the actions of the oppressed as they were reflected in these primary sources. The book has three central theses that have captured the attention of generations of readers and historians. The first was Williams’s almost offhand assertion that slavery had produced racism, not vice versa: “Slavery was not born of racism,” he contended, but “rather, racism was the consequence of slavery.” To begin with, “unfree labor in the New World was brown, white, black and yellow; Catholic, Protestant and pagan,” with various circumstances combining to promote the use of enslaved African labor. For example, “escape was easy for the white servant; less easy for the Negro,” who was “conspicuous by his color and features”—and, Williams added, “the Negro slave was cheaper.” But it was in North America most dramatically that slavery became encoded with “race” and thus, through its contorted rationalizations, ended up producing a new culture of racism.

This thesis was provocative for several reasons, but perhaps most of all because it implied that once the material roots of slavery had been ripped up, the modern world would finally witness the progressive erosion of anti-Black politics and culture. This optimistic view was echoed by the late Howard University classicist Frank Snowden in his trailblazing book Before Color Prejudice: The Ancient View of Blacks. Of course, sterner critics could well contend that such optimism was misplaced, that it misjudged the extent to which many post-slavery societies had been poisoned at the root. But this sunnier view of post-slavery societies was spawned in part by the proliferation of anti-colonial and anti–Jim Crow activism in the 1940s and ’50s.

Williams’s second thesis hasn’t stirred as much controversy, but it also exerted an enormous influence on the scholarship to come: He insisted that slavery fueled British industrial development, and therefore that slavery was the foundation not only of British capitalism but of capitalism as a whole. To prove this claim, Williams cited the many British mercantilists who themselves knew that slavery and the slave trade (not to mention the transportation of settlers) relied on a complex economic system, one that included shipbuilding and shackles to restrain the enslaved, along with firearms, textiles, and rum—manufacturing, in short. Sugar and tobacco, then cotton, were ferociously profitable, adding mightily to London’s coffers, which meant more ships and firearms, in a circle devoid of virtue. Assuredly, the immense wealth generated by slavery and the slave trade—the latter, at times, bringing a 1,700 percent profit—provided rocket fuel to boost the takeoff of capitalism itself.

If Williams’s first thesis has been critiqued by subsequent historians and scholars, who have found its apparent optimism about the ability to uproot racism misguided, his second has been largely embraced and bolstered by subsequent scholars, including Walter Rodney in How Europe Underdeveloped Africa and Joseph Inikori in Africans and the Industrial Revolution in England.

The latter, in fact, goes farther than Williams does. Inikori argues that before the advent of the slave trade, England’s West Yorkshire, the West Midlands, and South Lancashire were poorer regions; but buoyed by slavery’s economic stimulus, they became wealthy and industrialized. Similarly, in the period from 1650 to 1850, the Americas were effectively an extension of Africa itself in terms of exports, buoying the former to the detriment of the latter. More polemically, Rodney portrays Africa and Europe on a veritable seesaw, with one declining as the other rises, the two processes intrinsically united in a manner that echoes Williams.

The scholarship that followed Williams’s book also pointed to something that Williams missed in his account of the entwined nature of capitalism and slavery: The intense feudal religiosity that characterized Spain, Protestant England’s inquisitorial Catholic foe, began to yield in favor of a similarly intense racism—albeit shaped and formed by religion, just as racial slavery shaped and formed capitalism. As the historian Donald Matthews suggested in his book At the Altar of Lynching, this ultimate Jim Crow expression of hate—often featuring the immolation of the cross, if not of the victimized himself—was also a kind of religious sacrament as well as a holdover from a previous epoch in England’s history, in which Queen Mary I (also known as “Bloody Mary”) burned Protestant foes at the stake during her tumultuous and brief 16th-century reign. In the bumpy transition from feudalism to capitalism, there is a perverse devolutionary logic embedded in the shift from torching presumed heretics to torching actual Africans.

Nonetheless, Williams’s most disputed thesis was his downgrading of the heroic role of the British abolitionists. In his telling of their story, he argued that naked economic self-interest, more than morality or humanitarianism, drove England’s retreat from the slave trade in 1807 and its barring of slavery in 1833. Like The New York Times’ 1619 Project, this part of Williams’s argument pricked a sensitive nerve in the nation’s self-conception. In 2007, on the 200th anniversary of the official banning of human trafficking from Africa, the British prime minister and the monarch presided over a commemoration that sought to foreground Britain’s abolitionism, not its central role in the muck of slavery’s repulsiveness. Instead of focusing on the United Kingdom as a primary beneficiary of the enslavement of Africans, they refashioned their once formidable empire as the very embodiment of abolitionism.

PART 2:

This sleight-of-hand at once evaded the continuing legacy of slavery’s barbarity and undermined the question of reparations for the country’s crimes against humanity. The evasion eventually led one Black Britisher to argue that the plight of descendants of the enslaved in the UK was reminiscent of the movie The Truman Show, “where you know something is not right but nobody wants to admit it.”

When it comes to Britain’s subjects in North America, Williams shows how 1776 led to a disruption of the profitable chain of enrichment that linked the 13 colonies and the British Caribbean. The resulting republic, he said, “diminished the number of slaves in the empire and made abolition easier”—which is difficult to refute, though Williams curiously omitted the salient fact that the republic swiftly supplanted the monarchy as the kingpin of the African slave trade. Williams also illustrated how, in this void, the unpatriotic settlers who had broken from the British Empire were busily developing ties with the French Caribbean, heightening the profitability—and the exploitation—of those enslaved in what became Haiti. It was a process that would backfire spectacularly with the transformative revolution sparked in 1791; indeed, this was the revolution that led to abolition. (This thesis was explored in even greater depth in The Black Jacobins, by Williams’s frequent political sparring partner and fellow Trinidadian, C.L.R. James.)

Despite the convincing evidence that Williams deploys to make his case, this particular thesis is still routinely ignored by many contemporary historians, who argue that the abolitionist movement was ignited instead by the rebellion of 1776 and its purportedly liberatory message, often citing Vermont’s abolition decree in 1777. But as the unjustly neglected historian Harvey Amani Whitfield observes in The Problem of Slavery in Early Vermont, the language of this measure was sufficiently porous that even the family of settler hero Ethan Allen was implicated in the odiousness of enslavement. (More to the point, the decree could easily be seen as a cynically opportunistic last-ditch attempt to appeal to Africans who were already defecting to the Union Jack.)

In Capitalism and Slavery, Williams also stressed the agency of the enslaved and their role in abolishing slavery—“the most dynamic and powerful” force, he argued, and one that has been “studiously ignored.” Early on, Williams demonstrated, the enslaved sought to abolish slavery through insurrection, murder, poisonings, arson—“indolence, sabotage and revolt” was his descriptor of these actions—and he charts how these acts of militant resistance made their way back to London as well, where many took note and realized that lives and, more importantly, investments could be jeopardized. “Every white slave owner in Jamaica, Cuba or Texas,” Williams wrote, “lived in dread of another Toussaint L’Ouverture,” the true founder of revolutionary Haiti and the grandest abolitionist of all. Rather than accede to this “emancipation from below,” the British government, prodded by British abolitionists, opted for “emancipation from above.”

Williams’s masterwork is so rich with ideas and historical insights that it still speaks to today’s historiography, but in ways that have seemingly eluded many contemporary practitioners. For example, in his focus on England’s so-called Glorious Revolution of 1688—which unleashed a devastating era of “free trade in Africans,” as merchants descended on the beleaguered continent with the maniacal energy of crazed bees, manacling Africans and shipping them in breathtaking numbers to a cruel fate—Williams anticipated the illuminating contribution of the British historian William Pettigrew in his insightful Freedom’s Debt.

Part of the problem is that today’s historians are so siloed, narrowly focused on an era, such as 1750-83 or 1850-65, that they remain oblivious to preceding events—even ones as momentous as 1688, 1776’s true precursor. These scholars mimic the uncomprehending jury in the 1992 trial of the Los Angeles police officers whose vicious beating of Rodney King was captured on tape. Instead of allowing the tape to unfold seamlessly from beginning to end, sly defense attorneys exposed the jury to mere fragments and convinced its members that the disconnected episodes hardly amounted to a crime.

Indeed, just as slavery drove 1688, it assuredly compelled Texas’s secession from Mexico in 1836 and then—finally—the failure of 1861. And yes, along with the Royal Proclamation of 1763, which sought to restrain real estate speculators (including George Washington) from moving westward to seize Indigenous land, forcing London to expend blood and treasure, slavery was at the heart of 1776. As with many earthshaking events, the lust for land and enslaved labor drove the founding of the republic.

Williams also anticipated one of the more important scholarly interventions of recent decades: He offered an early account of the “construction of whiteness,” a subject written about in the enlightening work of David Roediger and Nell Irvin Painter, among others. The slave trade, Williams argued, “had become necessary to almost every nation in Europe.” As a result, a new identity politics of “whiteness”—militarized and monetized—had to emerge in order to justify the subjugation of continents and peoples and the gargantuan transfer of wealth to London, Paris, Copenhagen, Lisbon, Madrid, Amsterdam, and Washington. No insult to Brussels intended, but the formation of the United States was little more than a bloodier precursor of the European Union, manifested on an alien continent with a more coercive regime.

Inevitably, this cash machine of enslavement and the way it racialized humanity did not disappear when slavery itself was finally abolished. The legacy of racism persisted in Jim Crow, then in outrageously disparate health outcomes and the carceral system. There is no more illustrative example than the hellhole that is Angola State Penitentiary in Louisiana, which inelegantly carries the name of the region in Africa that produced a disproportionate share of the US enslaved—and thus today’s imprisoned.

Unfortunately, all of the jousting that Williams had to do with the mainstream of British and US historiography, which tended to downplay slave resistance while failing to think critically about capitalism as a system, prevented him from forging a larger political framework in the book that would have strengthened its historical insights. Encountering his discussion of the still-astonishing influx of enslaved Africans into Brazil in the 1840s, the uncareful reader could easily conclude that British nationals were largely responsible—and not US citizens. Perhaps understandably, Williams, who languished under the British Empire’s lash for decades, directed his ire toward London more than any other place—much in the way that James, his fellow countryman, focused intently on London’s malign role in subjugating revolutionary Haiti and hardly engaged with Washington’s.

Ironically, when he finally entered politics, Williams—who had so successfully broken from the pack on the soccer field and in his scholarship—managed to achieve only lesser results. Although Karl Marx, in Chapter 31 of the first volume of Capital, prefigured him in treating slavery in the Americas as essential to the rise of British industry, Williams was no Marxist—even if many of his peers in the Pan-African movement were decidedly of the socialist persuasion. This was true not only of James but of another Trinidadian, Claudia Jones, a former US Communist Party leader who was deported to London and became a stalwart of Black Britain (though she is better known today as a foremother of intersectionality). Jones was part of a circle that included Nelson Mandela and his successor, Thabo Mbeki, both of whom had been leading members of the South African Communist Party, as well as the similarly oriented founding fathers of postcolonial Africa: Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah; Angola’s Agostinho Neto; Mozambique’s Samora Machel; Guinea-Bissau’s Amilcar Cabral. All of these leaders were more than willing to receive aid from Moscow in order to combat their North Atlantic foes. Nonetheless, both Williams and those to his left still tended to see 1776 as the start of an “incomplete” revolution.

On this, there is much to dispute, and one might start by comparing the outcome of 1776 to the 1948 implantation of “apartheid” in another USA: the then Union of South Africa. Apartheid was founded with the central goal of uplifting the Afrikaner poor (akin to the “American dream”) while grinding Africans into neo-slavery (they objected strenuously, as did their counterparts in 1776). Decades earlier, the Afrikaners, who were the descendants of Dutch immigrants, had fought a putatively anti-colonial war against London, then sought to gobble up the land of their sprawling neighbor, today’s Namibia, not far from the size territorially of California and Texas combined, just as the Cherokee Nation was expropriated by Washington. Thus, as with 1776, the launch of apartheid South Africa could be deemed an “incomplete” revolution that somehow forgot to include the African majority—or was this exclusion and exploitation central to such a draconian intervention?

For his part, Williams the politician was forced to reckon with many of these knotty matters, in particular as they pertained to the purposefully incomplete process of decolonization and the rise of new forms of empire. As prime minister, in order to court the United States’ favor, he was derelict in extending solidarity to its antagonists in Cuba and neighboring Guyana, where Cheddi Jagan would be joined by Jamaica’s Michael Manley in seeking to pursue a noncapitalist path to independence.

Williams’s tenure as prime minister of Trinidad and Tobago extended for nearly two decades, from 1962 to 1981. But the presence of oil on the archipelago attracted the most vulturous wing of capital, further limiting his aspirations. As in Guyana, tensions between the various sectors of the working class—one with roots in Africa, the other in British India—were not conducive to anti-imperialist unity, hampering Williams’s ability to forge a sturdy base. Incongruously, though he did as much as any individual to assert the primacy of enslaved Africans in modern history, he ran afoul of the Black Power movement in his homeland, which—not altogether inaccurately—found him too compliant in dealing with the intrusive imperial presence in Trinidad. Yet despite being hampered by a divided working class and a proliferating Black Power movement that often regarded him with contempt, Williams was able to hang on to office, though he lacked the political strength to solve the persistent problems of poverty and underdevelopment.

The scholar whose X-ray vision detected the role of enslaved people in the innards of capitalism and empire was seemingly felled by both when the moment to confront their toxic legacy arrived. Even so, the failings of Williams the politico should not be used to vitiate the insights of Williams the scholar. As slavery-infused capitalism continues to run amok, we must, like an expert diagnostician, finally develop an adequate history that can drive a comprehensive prescription for our ills.

This sleight-of-hand at once evaded the continuing legacy of slavery’s barbarity and undermined the question of reparations for the country’s crimes against humanity. The evasion eventually led one Black Britisher to argue that the plight of descendants of the enslaved in the UK was reminiscent of the movie The Truman Show, “where you know something is not right but nobody wants to admit it.”

When it comes to Britain’s subjects in North America, Williams shows how 1776 led to a disruption of the profitable chain of enrichment that linked the 13 colonies and the British Caribbean. The resulting republic, he said, “diminished the number of slaves in the empire and made abolition easier”—which is difficult to refute, though Williams curiously omitted the salient fact that the republic swiftly supplanted the monarchy as the kingpin of the African slave trade. Williams also illustrated how, in this void, the unpatriotic settlers who had broken from the British Empire were busily developing ties with the French Caribbean, heightening the profitability—and the exploitation—of those enslaved in what became Haiti. It was a process that would backfire spectacularly with the transformative revolution sparked in 1791; indeed, this was the revolution that led to abolition. (This thesis was explored in even greater depth in The Black Jacobins, by Williams’s frequent political sparring partner and fellow Trinidadian, C.L.R. James.)

Despite the convincing evidence that Williams deploys to make his case, this particular thesis is still routinely ignored by many contemporary historians, who argue that the abolitionist movement was ignited instead by the rebellion of 1776 and its purportedly liberatory message, often citing Vermont’s abolition decree in 1777. But as the unjustly neglected historian Harvey Amani Whitfield observes in The Problem of Slavery in Early Vermont, the language of this measure was sufficiently porous that even the family of settler hero Ethan Allen was implicated in the odiousness of enslavement. (More to the point, the decree could easily be seen as a cynically opportunistic last-ditch attempt to appeal to Africans who were already defecting to the Union Jack.)

In Capitalism and Slavery, Williams also stressed the agency of the enslaved and their role in abolishing slavery—“the most dynamic and powerful” force, he argued, and one that has been “studiously ignored.” Early on, Williams demonstrated, the enslaved sought to abolish slavery through insurrection, murder, poisonings, arson—“indolence, sabotage and revolt” was his descriptor of these actions—and he charts how these acts of militant resistance made their way back to London as well, where many took note and realized that lives and, more importantly, investments could be jeopardized. “Every white slave owner in Jamaica, Cuba or Texas,” Williams wrote, “lived in dread of another Toussaint L’Ouverture,” the true founder of revolutionary Haiti and the grandest abolitionist of all. Rather than accede to this “emancipation from below,” the British government, prodded by British abolitionists, opted for “emancipation from above.”

Williams’s masterwork is so rich with ideas and historical insights that it still speaks to today’s historiography, but in ways that have seemingly eluded many contemporary practitioners. For example, in his focus on England’s so-called Glorious Revolution of 1688—which unleashed a devastating era of “free trade in Africans,” as merchants descended on the beleaguered continent with the maniacal energy of crazed bees, manacling Africans and shipping them in breathtaking numbers to a cruel fate—Williams anticipated the illuminating contribution of the British historian William Pettigrew in his insightful Freedom’s Debt.

Part of the problem is that today’s historians are so siloed, narrowly focused on an era, such as 1750-83 or 1850-65, that they remain oblivious to preceding events—even ones as momentous as 1688, 1776’s true precursor. These scholars mimic the uncomprehending jury in the 1992 trial of the Los Angeles police officers whose vicious beating of Rodney King was captured on tape. Instead of allowing the tape to unfold seamlessly from beginning to end, sly defense attorneys exposed the jury to mere fragments and convinced its members that the disconnected episodes hardly amounted to a crime.

Indeed, just as slavery drove 1688, it assuredly compelled Texas’s secession from Mexico in 1836 and then—finally—the failure of 1861. And yes, along with the Royal Proclamation of 1763, which sought to restrain real estate speculators (including George Washington) from moving westward to seize Indigenous land, forcing London to expend blood and treasure, slavery was at the heart of 1776. As with many earthshaking events, the lust for land and enslaved labor drove the founding of the republic.

Williams also anticipated one of the more important scholarly interventions of recent decades: He offered an early account of the “construction of whiteness,” a subject written about in the enlightening work of David Roediger and Nell Irvin Painter, among others. The slave trade, Williams argued, “had become necessary to almost every nation in Europe.” As a result, a new identity politics of “whiteness”—militarized and monetized—had to emerge in order to justify the subjugation of continents and peoples and the gargantuan transfer of wealth to London, Paris, Copenhagen, Lisbon, Madrid, Amsterdam, and Washington. No insult to Brussels intended, but the formation of the United States was little more than a bloodier precursor of the European Union, manifested on an alien continent with a more coercive regime.

Inevitably, this cash machine of enslavement and the way it racialized humanity did not disappear when slavery itself was finally abolished. The legacy of racism persisted in Jim Crow, then in outrageously disparate health outcomes and the carceral system. There is no more illustrative example than the hellhole that is Angola State Penitentiary in Louisiana, which inelegantly carries the name of the region in Africa that produced a disproportionate share of the US enslaved—and thus today’s imprisoned.

Unfortunately, all of the jousting that Williams had to do with the mainstream of British and US historiography, which tended to downplay slave resistance while failing to think critically about capitalism as a system, prevented him from forging a larger political framework in the book that would have strengthened its historical insights. Encountering his discussion of the still-astonishing influx of enslaved Africans into Brazil in the 1840s, the uncareful reader could easily conclude that British nationals were largely responsible—and not US citizens. Perhaps understandably, Williams, who languished under the British Empire’s lash for decades, directed his ire toward London more than any other place—much in the way that James, his fellow countryman, focused intently on London’s malign role in subjugating revolutionary Haiti and hardly engaged with Washington’s.

Ironically, when he finally entered politics, Williams—who had so successfully broken from the pack on the soccer field and in his scholarship—managed to achieve only lesser results. Although Karl Marx, in Chapter 31 of the first volume of Capital, prefigured him in treating slavery in the Americas as essential to the rise of British industry, Williams was no Marxist—even if many of his peers in the Pan-African movement were decidedly of the socialist persuasion. This was true not only of James but of another Trinidadian, Claudia Jones, a former US Communist Party leader who was deported to London and became a stalwart of Black Britain (though she is better known today as a foremother of intersectionality). Jones was part of a circle that included Nelson Mandela and his successor, Thabo Mbeki, both of whom had been leading members of the South African Communist Party, as well as the similarly oriented founding fathers of postcolonial Africa: Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah; Angola’s Agostinho Neto; Mozambique’s Samora Machel; Guinea-Bissau’s Amilcar Cabral. All of these leaders were more than willing to receive aid from Moscow in order to combat their North Atlantic foes. Nonetheless, both Williams and those to his left still tended to see 1776 as the start of an “incomplete” revolution.

On this, there is much to dispute, and one might start by comparing the outcome of 1776 to the 1948 implantation of “apartheid” in another USA: the then Union of South Africa. Apartheid was founded with the central goal of uplifting the Afrikaner poor (akin to the “American dream”) while grinding Africans into neo-slavery (they objected strenuously, as did their counterparts in 1776). Decades earlier, the Afrikaners, who were the descendants of Dutch immigrants, had fought a putatively anti-colonial war against London, then sought to gobble up the land of their sprawling neighbor, today’s Namibia, not far from the size territorially of California and Texas combined, just as the Cherokee Nation was expropriated by Washington. Thus, as with 1776, the launch of apartheid South Africa could be deemed an “incomplete” revolution that somehow forgot to include the African majority—or was this exclusion and exploitation central to such a draconian intervention?

For his part, Williams the politician was forced to reckon with many of these knotty matters, in particular as they pertained to the purposefully incomplete process of decolonization and the rise of new forms of empire. As prime minister, in order to court the United States’ favor, he was derelict in extending solidarity to its antagonists in Cuba and neighboring Guyana, where Cheddi Jagan would be joined by Jamaica’s Michael Manley in seeking to pursue a noncapitalist path to independence.

Williams’s tenure as prime minister of Trinidad and Tobago extended for nearly two decades, from 1962 to 1981. But the presence of oil on the archipelago attracted the most vulturous wing of capital, further limiting his aspirations. As in Guyana, tensions between the various sectors of the working class—one with roots in Africa, the other in British India—were not conducive to anti-imperialist unity, hampering Williams’s ability to forge a sturdy base. Incongruously, though he did as much as any individual to assert the primacy of enslaved Africans in modern history, he ran afoul of the Black Power movement in his homeland, which—not altogether inaccurately—found him too compliant in dealing with the intrusive imperial presence in Trinidad. Yet despite being hampered by a divided working class and a proliferating Black Power movement that often regarded him with contempt, Williams was able to hang on to office, though he lacked the political strength to solve the persistent problems of poverty and underdevelopment.

The scholar whose X-ray vision detected the role of enslaved people in the innards of capitalism and empire was seemingly felled by both when the moment to confront their toxic legacy arrived. Even so, the failings of Williams the politico should not be used to vitiate the insights of Williams the scholar. As slavery-infused capitalism continues to run amok, we must, like an expert diagnostician, finally develop an adequate history that can drive a comprehensive prescription for our ills.

How Proslavery Was the Constitution?

How Proslavery Was the Constitution?

Nicholas Guyatt

Sean Wilentz’s ‘No Property in Man: Slavery and Antislavery at the Nation’s Founding’

June 6, 2019 issue

Submit a letter:

Email us letters@nybooks.com

Reviewed:

No Property in Man: Slavery and Antislavery at the Nation’s Founding

by Sean Wilentz

Harvard University Press, 350 pp., $26.95

Titus Kaphar/Jeremy Lawson

Titus Kaphar: Page 4 of Jefferson’s ‘Farm Book’…, 2018. That page of Jefferson’s ledger lists the names of enslaved people on his plantation at Monticello in January 1774.

Were the Founding Fathers responsible for American slavery? William Lloyd Garrison, the celebrated abolitionist, certainly thought so. In an uncompromising address in Framingham, Massachusetts, on July 4, 1854, Garrison denounced the hypocrisy of a nation that declared that “all men are created equal” while holding nearly four million African-Americans in bondage. The US Constitution was hopelessly implicated in this terrible crime, Garrison claimed: it kept free states like Massachusetts in a union with slave states like South Carolina, and it increased the influence of slave states in the House of Representatives and the Electoral College by counting enslaved people as three fifths of a human being. When Garrison finished excoriating the Founders, he pulled a copy of the Constitution from his pocket, branded it “a covenant with death and an agreement with hell,” and set it on fire.

Garrison was one of the most unpopular men in nineteenth-century America, and this performance did little to improve his standing with the moderates of his time. Today’s historians are more sympathetic to his argument that the Constitution made possible the expansion of slavery in the early United States. According to Ibram X. Kendi, author of the National Book Award–winning Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America (2016), the Constitution “enshrined the power of slaveholders and racist ideas in the nation’s founding document.” David Waldstreicher, in Slavery’s Constitution (2009), charges that the Founders produced “a proslavery constitution, in intention and effect.”

Their bleak assessments are grounded in the many protections for slaveholding agreed on at the Constitutional Convention of 1787. Beyond the three-fifths rule, the international slave trade was exempted from regulation by the federal government, which otherwise oversaw foreign commerce. Congress was banned from abolishing the trade until 1808 at the earliest. The federal government was prevented from introducing a head tax on slaves, and free states were forbidden from harboring runaways from slave states. The Founders obliged Congress to “suppress insurrections,” committing the national government to put down slave rebellions. The abolitionist Wendell Phillips, an associate of Garrison’s, summarized the work of the Founders in 1845: “Willingly, with deliberate purpose, our fathers bartered honesty for gain, and became partners with tyrants, that they might share in the profits of their tyranny.”

The effectiveness of constitutional protections for slavery can be measured in the growth of the institution between the formation of the federal government in 1789 and the secession of South Carolina in 1860. Across these seven decades, the number of enslaved people in the United States increased from 700,000 to four million. The dispossession of Native Americans and the violent seizure of northern Mexico created a vast cotton belt that stretched from the Atlantic to the Rio Grande. Although Congress opted to abolish the international slave trade at the earliest opportunity in 1808, a vast domestic trade—expressly permitted by the Constitution—relocated more than a million enslaved people from upper southern states like Maryland and Virginia to the cotton fields of the Deep South. Unspeakable crimes were committed against African-Americans; countless lives were broken or ended. While individual slaveholders bore their share of responsibility, the Constitution allowed proslavery forces to use the power of the federal government to support appalling measures. With the Dred Scott decision of 1857, which denied the possibility of black citizenship in America and invited slaveholders to take their property into any state of the Union, slavery’s domination of national politics seemed absolute.

Sean Wilentz’s No Property in Man concedes the horrors of slavery and acknowledges that the Constitution benefited slaveholders. For Wilentz, though, fixating on the Constitution’s proslavery effects or racist underpinning overlooks a “crucial subtlety” at the heart of the 1787 Constitutional Convention: while the delegates in Philadelphia encouraged and rewarded slaveholders, they refused to validate the principle of “property in man.”

Most books about the Constitution, even the ones that largely ignore slavery, acknowledge that the Convention walked a difficult line on the question. By 1787, in five of the original thirteen states, the legislature had outlawed slavery or the state supreme court had ended it. Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Connecticut had passed gradual emancipation bills, which ensured that slavery in those states would survive into the nineteenth century. In New Hampshire and Massachusetts, legal challenges under the new state constitutions brought slavery to a sudden end. New York and New Jersey had already started debating emancipation before the Constitutional Convention. They finally opted for their own gradual schemes in 1799 and 1804, respectively.

Economic and demographic developments encouraged the view that slavery was in retreat in the 1780s. In Virginia, which had more slaves than any other state throughout the antebellum period, soil exhaustion and trade disruption persuaded many white planters to shift from tobacco to less labor-intensive wheat farming. Virginia’s legislators made it easier for individual slaveholders to manumit their slaves. Throughout the upper South, writers and activists disputed the idea that the region’s future depended on the perpetuation of slavery. The holdouts in this fragile antislavery moment were the Deep South states, principally Georgia and South Carolina. Even here, white voices were raised against slavery, but the political elite was deeply committed to the persistence of human bondage. “If it is debated, whether their slaves are their property,” one South Carolina politician had warned the Continental Congress in 1776, “there is an end of the confederation.”

If eleven of the thirteen states were antislavery or skeptical about slavery’s future, why were Georgia and South Carolina given so much leeway in the Constitutional Convention? Wilentz offers a familiar answer: had any plan for emancipation been discussed, “the slaveholding states, above all the Lower South, would have never ratified such a Constitution.” There’s a comforting finality about the logic of this: the delegates at Philadelphia did the best they could, but it was simply impossible to craft a strong central government in 1787 without sweeping concessions to slavery.

Wilentz’s book has little to say about two questions that would illuminate what is often called the “paradox of liberty”: Were threats of disunion from South Carolina and Georgia credible? And might the Virginia delegation, under the enlightened leadership of James Madison, have led the upper South (and the nation) toward a happier future? Instead Wilentz focuses on the ways in which the Deep South delegates, occasionally (but not always) supported by their fellow slaveholders in the upper South, were frustrated in their efforts to obtain an even more proslavery Constitution. Rather than viewing the Philadelphia delegates as pusillanimous on the slavery question, Wilentz sees them playing a long game: by consciously and doggedly affirming “no property in man,” the Founders insisted that freedom, rather than slavery, was the principle at the core of the new nation.

Wilentz admits there are problems with this argument. It’s easy to understand why historians believe that slaveholding interests triumphed at Philadelphia, “because in several respects they did.” He does not dispute that slavery emerged intact from the 1787 Convention, but insists that “the Constitution’s proslavery features appear substantial but incomplete.” There is a surreal quality to some of his counterfactuals in this respect. (What if the Deep South had forced the delegates to pass a five-fifths rule?)

But for the most part he looks to later developments. The exclusion of “property in man” became “the Achilles’ heel of proslavery politics.” It offered a critical opening to subsequent generations of antislavery campaigners and politicians, who could—and eventually did—point to the absence of absolute constitutional guarantees of slavery’s legitimacy. Most notably, Wilentz suggests that the Republican Party of the 1850s used the Constitution as “the means to hasten slavery’s demise.” By declining to make an explicit declaration in 1787 that slavery was a foundational principle of the United States, the Founders had brilliantly facilitated the later Republican cry of “Freedom National, Slavery Sectional.”

Our view about whether the Constitution hastened abolition may depend on how we understand slavery’s effects in the seventy-five years between the Constitutional Convention and the Emancipation Proclamation. As Calvin Schermerhorn argues in Unrequited Toil (2018), his recent book on the development of slavery in the United States, the expansion of the institution under the provisions of the Constitution did incalculable damage to African-Americans, while hugely increasing the wealth of white people. By 1860, enslaved people counted for nearly 20 percent of national wealth and produced nearly 60 percent of the nation’s exports. Historians and economists debate the centrality of slavery to the emergence of modern American capitalism, but few dispute that the gains of slavery—through shipping, banking, insurance, and commerce—were distributed nationally.

Wilentz writes that the exclusion of an explicit guarantee of property in man was not just an accident or “technicality” at the Constitutional Convention. The delegates “insisted” on it, he claims, and he offers a line from James Madison to prove his point: it would be wrong “to admit in the Constitution the idea that there could be property in men.” This quotation is so perfect for Wilentz’s argument that he could not have invented better evidence in support of it.

But there is some doubt as to whether Madison actually used those words in Philadelphia. The debates at the Convention were held in secret, and the only person who kept substantial notes on what had been said was Madison himself. The legal historian Mary Sarah Bilder won the Bancroft Prize in 2016 for Madison’s Hand: Revising the Constitutional Convention, a brilliant study of just how extensively Madison reshaped the story of what happened at Philadelphia over his long lifetime. On the subject of slavery, she believes that Madison tinkered with the transcript of 1787 to make himself seem more righteous than he actually had been; she suspects that the specific reference to “property in men” was added at a later date. This doesn’t destroy Wilentz’s argument that “no property in man” was a discrete principle with political power, especially in the nineteenth century. But the notion that Madison and his colleagues planted antislavery language in the Constitution for Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass to discover in the 1850s is more exciting than convincing.

Madison is a tantalizing figure for Wilentz. The disputed quotation decrying “property in men” appears half a dozen times in his book, with Bilder’s qualms relegated to an endnote. Wilentz explains sympathetically that when Madison declared during the Virginia ratification debates that the Constitution provides strong protection for slavery via the fugitive slave clause, the Founder was “stuck in a dilemma that made candor impossible.” When evidence of antislavery intent dries up, Wilentz tells us that Madison was taking an influential stand against property in man even if he “could not or would not admit [it], not even, perhaps, to himself.”

How Proslavery Was the Constitution?

Nicholas Guyatt

Sean Wilentz’s ‘No Property in Man: Slavery and Antislavery at the Nation’s Founding’

June 6, 2019 issue

Submit a letter:

Email us letters@nybooks.com

Reviewed:

No Property in Man: Slavery and Antislavery at the Nation’s Founding

by Sean Wilentz

Harvard University Press, 350 pp., $26.95

Titus Kaphar/Jeremy Lawson

Titus Kaphar: Page 4 of Jefferson’s ‘Farm Book’…, 2018. That page of Jefferson’s ledger lists the names of enslaved people on his plantation at Monticello in January 1774.

Were the Founding Fathers responsible for American slavery? William Lloyd Garrison, the celebrated abolitionist, certainly thought so. In an uncompromising address in Framingham, Massachusetts, on July 4, 1854, Garrison denounced the hypocrisy of a nation that declared that “all men are created equal” while holding nearly four million African-Americans in bondage. The US Constitution was hopelessly implicated in this terrible crime, Garrison claimed: it kept free states like Massachusetts in a union with slave states like South Carolina, and it increased the influence of slave states in the House of Representatives and the Electoral College by counting enslaved people as three fifths of a human being. When Garrison finished excoriating the Founders, he pulled a copy of the Constitution from his pocket, branded it “a covenant with death and an agreement with hell,” and set it on fire.

Garrison was one of the most unpopular men in nineteenth-century America, and this performance did little to improve his standing with the moderates of his time. Today’s historians are more sympathetic to his argument that the Constitution made possible the expansion of slavery in the early United States. According to Ibram X. Kendi, author of the National Book Award–winning Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America (2016), the Constitution “enshrined the power of slaveholders and racist ideas in the nation’s founding document.” David Waldstreicher, in Slavery’s Constitution (2009), charges that the Founders produced “a proslavery constitution, in intention and effect.”

Their bleak assessments are grounded in the many protections for slaveholding agreed on at the Constitutional Convention of 1787. Beyond the three-fifths rule, the international slave trade was exempted from regulation by the federal government, which otherwise oversaw foreign commerce. Congress was banned from abolishing the trade until 1808 at the earliest. The federal government was prevented from introducing a head tax on slaves, and free states were forbidden from harboring runaways from slave states. The Founders obliged Congress to “suppress insurrections,” committing the national government to put down slave rebellions. The abolitionist Wendell Phillips, an associate of Garrison’s, summarized the work of the Founders in 1845: “Willingly, with deliberate purpose, our fathers bartered honesty for gain, and became partners with tyrants, that they might share in the profits of their tyranny.”