https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2021/06/10/myth-alamo-gets-history-all-wrong/

The myth of Alamo gets the history all wrong

Instead of a heroic stance for freedom, Texans fought to be able to enslave people

The Alamo is best known as the site of a legendary 1836 battle, but the popular understanding of the history of that battle gets the causes wrong. (Eric Gay/AP)

By Bryan Burrough

and

Jason Stanford

June 10, 2021 at 6:00 a.m. EDT

The 1836 battle for the Alamo is remembered as a David vs. Goliath story. A band of badly outnumbered Texans fought against oppression by the Mexican dictator Santa Anna, holding off the siege long enough for Sam Houston to move the main rebel force east and providing them a rallying cry at the Battle of San Jacinto. As almost any Texan will tell you, their heroic sacrifice turned the Alamo into the cradle of Texas liberty.

American presidents have even invoked the Alamo myth to inspire their citizens in battles of all kinds, from Lyndon B. Johnson during the Vietnam War to then-candidate George W. Bush, who read William Travis’s iconic “Victory or Death!” letter to inspire the U.S. team to win the 1999 Ryder Cup. And in his last State of the Union address, Donald Trump, perhaps inspiring Americans to an internal battle, referenced “Texas patriots [who] made their last stand at the Alamo. The beautiful, beautiful Alamo.”

Yet, the legend of the Alamo is a Texas tall tale run amok. The actual story is one of White American immigrants to Texas revolting in large part over Mexican attempts to end slavery. Far from heroically fighting for a noble cause, they fought to defend the most odious of practices. Our newfound understanding of this history presents Americans with a long-overlooked opportunity to correct a racist myth surrounding this monument.

Anglo settlers began arriving in Texas from the United States in the 1820s, when it was part of Spanish Mexico. The Spanish government wanted them as a bulwark against the Comanche, but these new Texans had another agenda. They wanted to take advantage of thousands of acres of land in the Brazos River Valley that was available cheap for White settlers, some of which was used to cultivate cotton.

When these dichotomous visions became clear in 1822, a newly independent Mexican government in Mexico City paused further settlement. The problem, according to Stephen F. Austin, known as the “Father of Texas,” was that the new government, which took power on a racial equality agenda, would not abide slavery.

The Mexican government’s efforts to write a new federal constitution got bogged down. One of the sticking points was the question of slavery. The new government wanted slavery gone, but ending the practice would ruin the settlers. Austin, “talked to each individual member of the junta of the necessity which existed in Texas … for the new colonists to bring their slaves.”

And the Mexican government couldn’t just ignore their whims. The Anglo settlers were increasingly taking over the place and could, if their numbers increased sufficiently, break Texas off from Mexico and join the United States, which, of course, eventually happened.

So the Mexican government struck a deal with Austin. The deal allowed settlers to keep their enslaved people but banned any further trade. Enslavement took root, and in 1823, Austin received permission to increase immigration from the United States.

But constant turnover and instability in Mexico City proved problematic for the Texans. In 1824, a new government proposed measures to undo the understanding over slavery. One bill outlawed “commerce and traffic in slaves” and stated that any enslaved person brought into Mexico would be deemed free by “the mere act of treading Mexican soil.”

Potential settlers noticed. One prospective settler from Mississippi noted that the only thing preventing “wealthy planters from emigrating immediately to the province of Texas,” was the “uncertainty now prevailing” over slavery. And from Alabama came a similar message: “Our most valuable inhabitants here own negroes. … Our planters are not willing to remove without they can first be assured of their being secured to them by the laws of your Govt.” Economic opportunity made Texas alluring for cotton growers, but the political uncertainty made them hesitate. Their hesitation, in turn, increased pressure on Mexican lawmakers, who wanted to maintain control of Texas, and on Austin, whose livelihood depended on getting more people to immigrate.

Finally, in 1824, a new Mexican constitution seemed to settle the issue by leaving the slavery question to the states. The locus of Austin’s anxiety shifted to Saltillo, the capital of the Mexican state of Coahuila, to which the Texas territory belonged. The state constitution of 1827 allowed settlers to import enslaved people for six more months. That September, however, yet another new government in Mexico City passed a flurry of laws curbing slavery.

By 1828, Texans had settled on an unsustainable practice: They would ignore anti-slavery laws passed in Mexico City.

Discussion that the government might actually enforce the 1827 laws, though, brought talk of war. “Many have announced to me that there will be a revolution if the law takes effect,” a Mexican military commander in East Texas wrote a superior. “Austin’s colony would be the first to think along these lines. It was formed for slavery, and without it her inhabitants would be nothing.”

This talk of secession brought crackdowns from the Mexican government, including taxes on cotton to pay for military installations in Texas and an order to close the border with the United States. Austin sunk into a depression. Mexico was threatening the foundation of Texans’ economy. “Nothing is wanted but money,” Austin wrote in one letter, adding in another, “and negros are necessary to make it.”

Cotton was booming, though, which boosted illegal immigration into Texas. Americans, though still a minority, were fast on their way to becoming a majority. This demographic shift increased Mexico’s efforts to directly control Texas, including newfound enforcement of laws. Texans, accustomed to a la carte obedience to Mexican law, took this affront as tyranny.

In April 1832, the Mexican government closed a loophole allowing settlers to reclassify their human chattel as indentured servants. This finally outlawed slavery, full stop. For Austin, this was the last straw. “Texas must be a slave country,” he wrote a friend, “circumstances and unavoidable necessity compels it.”

He saw only two options: a separate Mexican statehood for Texas with legal slavery or rebellion. “No middle course left,” he wrote.

When the Mexican government granted Santa Anna dictatorial powers in 1834, Mexican states revolted, first Zacatecas, then Coahuila, which included Texas. The Mexican army marched north to put down the rebellions. In Matagorda, a group of Anglo settlers declared that “merciless soldiery” was coming “to give liberty to our slaves, and to make slaves of ourselves.”

The Texas leadership justified the war as a fight to preserve their “natural rights” and — that word again — their “property,” meaning their enslaved laborers.

Even in Washington it was clear what drove the Texans. Abolitionists denounced their insurgency as the world’s first proslavery rebellion. “The war now raging in Texas,” charged former president and Rep. John Quincy Adams (Mass.), was “a war for the reestablishment of Slavery where it was abolished. It is not a servile war, but a war between Slavery and Emancipation, and every possible effort has been made to drive us into this war, on the side of slavery.”

The Texas Revolt may have been precipitated by ham-handed Mexican attempts to exercise control over its territory, but the underlying cause, was the one thing American immigrants and the Mexican government had disagreed on since the beginning: the preservation of slavery.

Given that its defenders were fighting to form what became the single most militant slave nation in history, that men who fought at the Alamo like Jim Bowie and William Travis traded enslaved people, and Austin, the “Father of Texas,” spent years fighting to preserve slavery from the attacks of Mexican abolitionists, it is clear that rather than a courageous stand for liberty, the White men fighting at the Alamo were battling to own people of color.

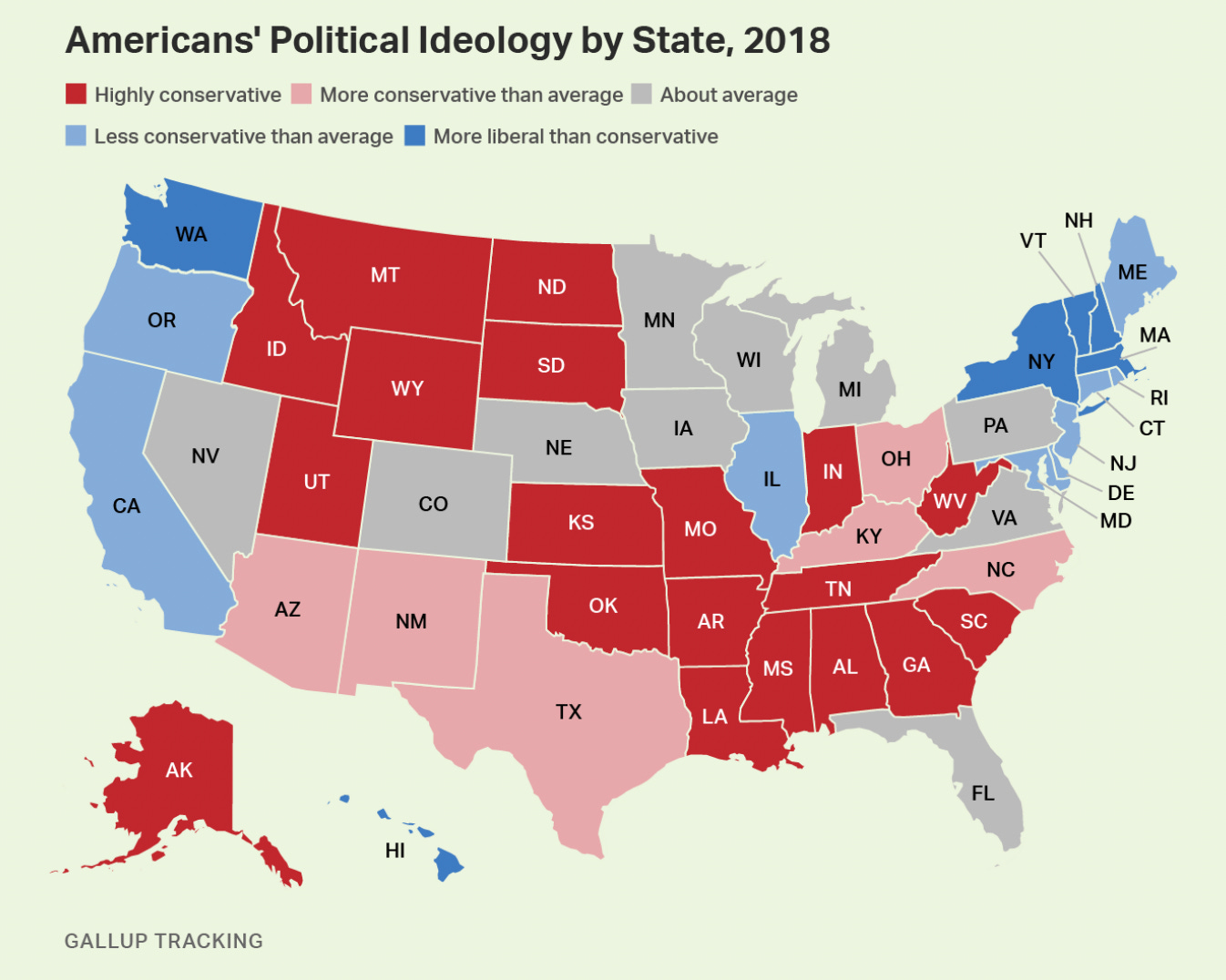

To many in Texas, the Alamo is a secular shrine to conservative values on par with a Confederate monument, a metaphor made literal in 2019 when the Texas Senate specifically included the Alamo in legislation to protect Confederate monuments from removal. The debate over the history of White supremacy has only expanded since then, most recently in debates over teaching critical race theory and with the first national reckoning over the Tulsa Massacre. With the debate over our past increasingly fraught, reexamining the Alamo’s history shines a spotlight on how slavery played a role in the formation of the Southwest and how its impact has lingered, fueling an ethos at the core of Texas identity and, as Trump’s last State of the Union shows, that continues to animate conservative ideology.

The myth of Alamo gets the history all wrong

Instead of a heroic stance for freedom, Texans fought to be able to enslave people

The Alamo is best known as the site of a legendary 1836 battle, but the popular understanding of the history of that battle gets the causes wrong. (Eric Gay/AP)

By Bryan Burrough

and

Jason Stanford

June 10, 2021 at 6:00 a.m. EDT

The 1836 battle for the Alamo is remembered as a David vs. Goliath story. A band of badly outnumbered Texans fought against oppression by the Mexican dictator Santa Anna, holding off the siege long enough for Sam Houston to move the main rebel force east and providing them a rallying cry at the Battle of San Jacinto. As almost any Texan will tell you, their heroic sacrifice turned the Alamo into the cradle of Texas liberty.

American presidents have even invoked the Alamo myth to inspire their citizens in battles of all kinds, from Lyndon B. Johnson during the Vietnam War to then-candidate George W. Bush, who read William Travis’s iconic “Victory or Death!” letter to inspire the U.S. team to win the 1999 Ryder Cup. And in his last State of the Union address, Donald Trump, perhaps inspiring Americans to an internal battle, referenced “Texas patriots [who] made their last stand at the Alamo. The beautiful, beautiful Alamo.”

Yet, the legend of the Alamo is a Texas tall tale run amok. The actual story is one of White American immigrants to Texas revolting in large part over Mexican attempts to end slavery. Far from heroically fighting for a noble cause, they fought to defend the most odious of practices. Our newfound understanding of this history presents Americans with a long-overlooked opportunity to correct a racist myth surrounding this monument.

Anglo settlers began arriving in Texas from the United States in the 1820s, when it was part of Spanish Mexico. The Spanish government wanted them as a bulwark against the Comanche, but these new Texans had another agenda. They wanted to take advantage of thousands of acres of land in the Brazos River Valley that was available cheap for White settlers, some of which was used to cultivate cotton.

When these dichotomous visions became clear in 1822, a newly independent Mexican government in Mexico City paused further settlement. The problem, according to Stephen F. Austin, known as the “Father of Texas,” was that the new government, which took power on a racial equality agenda, would not abide slavery.

The Mexican government’s efforts to write a new federal constitution got bogged down. One of the sticking points was the question of slavery. The new government wanted slavery gone, but ending the practice would ruin the settlers. Austin, “talked to each individual member of the junta of the necessity which existed in Texas … for the new colonists to bring their slaves.”

And the Mexican government couldn’t just ignore their whims. The Anglo settlers were increasingly taking over the place and could, if their numbers increased sufficiently, break Texas off from Mexico and join the United States, which, of course, eventually happened.

So the Mexican government struck a deal with Austin. The deal allowed settlers to keep their enslaved people but banned any further trade. Enslavement took root, and in 1823, Austin received permission to increase immigration from the United States.

But constant turnover and instability in Mexico City proved problematic for the Texans. In 1824, a new government proposed measures to undo the understanding over slavery. One bill outlawed “commerce and traffic in slaves” and stated that any enslaved person brought into Mexico would be deemed free by “the mere act of treading Mexican soil.”

Potential settlers noticed. One prospective settler from Mississippi noted that the only thing preventing “wealthy planters from emigrating immediately to the province of Texas,” was the “uncertainty now prevailing” over slavery. And from Alabama came a similar message: “Our most valuable inhabitants here own negroes. … Our planters are not willing to remove without they can first be assured of their being secured to them by the laws of your Govt.” Economic opportunity made Texas alluring for cotton growers, but the political uncertainty made them hesitate. Their hesitation, in turn, increased pressure on Mexican lawmakers, who wanted to maintain control of Texas, and on Austin, whose livelihood depended on getting more people to immigrate.

Finally, in 1824, a new Mexican constitution seemed to settle the issue by leaving the slavery question to the states. The locus of Austin’s anxiety shifted to Saltillo, the capital of the Mexican state of Coahuila, to which the Texas territory belonged. The state constitution of 1827 allowed settlers to import enslaved people for six more months. That September, however, yet another new government in Mexico City passed a flurry of laws curbing slavery.

By 1828, Texans had settled on an unsustainable practice: They would ignore anti-slavery laws passed in Mexico City.

Discussion that the government might actually enforce the 1827 laws, though, brought talk of war. “Many have announced to me that there will be a revolution if the law takes effect,” a Mexican military commander in East Texas wrote a superior. “Austin’s colony would be the first to think along these lines. It was formed for slavery, and without it her inhabitants would be nothing.”

This talk of secession brought crackdowns from the Mexican government, including taxes on cotton to pay for military installations in Texas and an order to close the border with the United States. Austin sunk into a depression. Mexico was threatening the foundation of Texans’ economy. “Nothing is wanted but money,” Austin wrote in one letter, adding in another, “and negros are necessary to make it.”

Cotton was booming, though, which boosted illegal immigration into Texas. Americans, though still a minority, were fast on their way to becoming a majority. This demographic shift increased Mexico’s efforts to directly control Texas, including newfound enforcement of laws. Texans, accustomed to a la carte obedience to Mexican law, took this affront as tyranny.

In April 1832, the Mexican government closed a loophole allowing settlers to reclassify their human chattel as indentured servants. This finally outlawed slavery, full stop. For Austin, this was the last straw. “Texas must be a slave country,” he wrote a friend, “circumstances and unavoidable necessity compels it.”

He saw only two options: a separate Mexican statehood for Texas with legal slavery or rebellion. “No middle course left,” he wrote.

When the Mexican government granted Santa Anna dictatorial powers in 1834, Mexican states revolted, first Zacatecas, then Coahuila, which included Texas. The Mexican army marched north to put down the rebellions. In Matagorda, a group of Anglo settlers declared that “merciless soldiery” was coming “to give liberty to our slaves, and to make slaves of ourselves.”

The Texas leadership justified the war as a fight to preserve their “natural rights” and — that word again — their “property,” meaning their enslaved laborers.

Even in Washington it was clear what drove the Texans. Abolitionists denounced their insurgency as the world’s first proslavery rebellion. “The war now raging in Texas,” charged former president and Rep. John Quincy Adams (Mass.), was “a war for the reestablishment of Slavery where it was abolished. It is not a servile war, but a war between Slavery and Emancipation, and every possible effort has been made to drive us into this war, on the side of slavery.”

The Texas Revolt may have been precipitated by ham-handed Mexican attempts to exercise control over its territory, but the underlying cause, was the one thing American immigrants and the Mexican government had disagreed on since the beginning: the preservation of slavery.

Given that its defenders were fighting to form what became the single most militant slave nation in history, that men who fought at the Alamo like Jim Bowie and William Travis traded enslaved people, and Austin, the “Father of Texas,” spent years fighting to preserve slavery from the attacks of Mexican abolitionists, it is clear that rather than a courageous stand for liberty, the White men fighting at the Alamo were battling to own people of color.

To many in Texas, the Alamo is a secular shrine to conservative values on par with a Confederate monument, a metaphor made literal in 2019 when the Texas Senate specifically included the Alamo in legislation to protect Confederate monuments from removal. The debate over the history of White supremacy has only expanded since then, most recently in debates over teaching critical race theory and with the first national reckoning over the Tulsa Massacre. With the debate over our past increasingly fraught, reexamining the Alamo’s history shines a spotlight on how slavery played a role in the formation of the Southwest and how its impact has lingered, fueling an ethos at the core of Texas identity and, as Trump’s last State of the Union shows, that continues to animate conservative ideology.