Vaccines beat natural immunity in fight against COVID-19

Vaccines beat natural immunity in fight against COVID-19

The best protection against COVID-19? Getting vaccinated, not waiting for illness to create natural immunity, says infectious disease expert Anna Durbin

Vaccines beat natural immunity in fight against COVID-19

Vaccines beat natural immunity in fight against COVID-19

The best protection against COVID-19? Getting vaccinated, not waiting for illness to create natural immunity, says infectious disease expert Anna Durbin

Katie Pearce

/ Sep 10

A common reason cited for not getting vaccinated against COVID-19—especially among the young and healthy—is "I trust my immune system" or some variation of that line. The same goes for those who have already had the virus and assume they've developed some natural immunity.

Though the human immune system is indeed an extraordinary mechanism, it's not worth gambling with a disease as unpredictable and serious as COVID-19, says infectious disease expert

Anna Durbin, a professor of international health at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine.

"It's Russian roulette," she says. "Young people tend to think they're invincible. But it just takes that one slip and your entire life could change."

With the delta variant,

we're seeing many more young people on ventilators in hospitals and dying, Durbin says. And declining the vaccine is more than just a personal decision: An infected person can easily transmit the virus to others, including immunocompromised people at higher risk for grave illness and children under 12 who can't yet access the vaccines.

During a conversation with the Hub, Durbin, a faculty member at the

Center for Immunization Research, talked about some of the popular misconceptions surrounding natural immunity and the purpose of vaccines.

What would you say to someone who wants to put their faith in their own immune system with COVID-19?

It's not a good idea. Yes, natural infection does provide some immunity, so the next time you get that disease, you won't get as sick. But here's the problem: Your first encounter with that disease could go very wrong. With COVID-19, you could end up very ill, you could end up in the hospital, or you could die. We're seeing huge rates of hospitalizations and deaths, and you don't want to risk becoming one of those statistics. And there are other potential complications: You could lose your sense of taste and smell for months, you could develop long-haul COVID-19. It's an unpredictable disease, and we don't know how it's going to hit different people.

That's where the vaccines come in. Vaccines provide protection without any of the morbidities you can get with a natural COVID-19 protection. We don't have vaccines for things like the common cold because most people don't get very sick from that, so it's not worth the effort to make different vaccines for every different cold virus. But when we see viruses or other bacteria that can cause severe illness, like COVID-19, we need the protection of a vaccine to prevent the hospitalizations and deaths. Vaccines are the reason we no longer see so many other diseases that people suffered from in the past: smallpox, measles, polio, even chicken pox.

For those who have already had COVID-19 in the past, why would a vaccine still be necessary?

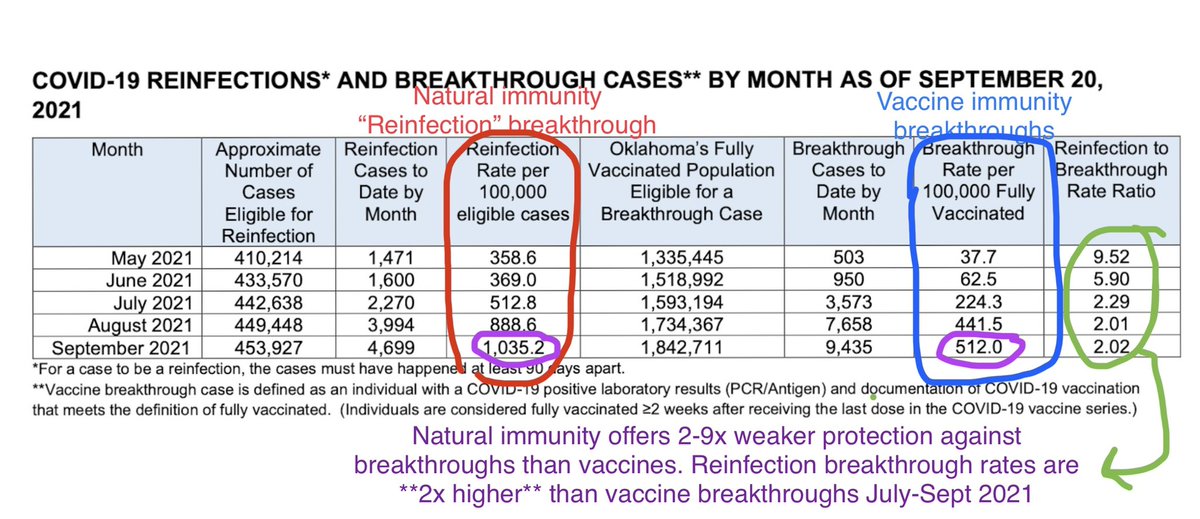

The vaccines still lower your risks. We have evidence showing that if you've been naturally infected with COVID-19 and you aren't vaccinated,

your risk of getting reinfected with symptomatic disease is about 2.5–fold higher. When you introduce the vaccine to someone who's already had COVID-19, the body says, "Hey, I remember that, I'm going to stimulate the immune response so you're protected." You're pumping up your antibodies to higher levels so they can stop the virus before it enters your system.

"We're seeing some breakthrough infections among vaccinated people and will continue to, but that's expected and doesn't mean the vaccines are failing."

Professor, Bloomberg School of Public Health and Johns Hopkins School of Medicine

So would someone who's had both COVID-19 and the vaccine have the most protection possible?

There's no doubt that natural infection confers immunity, and we're seeing some evidence—not surprising—that a previous COVID-19 infection

plus vaccination provides more durable protection than simply vaccines alone. But that doesn't mean that vaccinated people should go out there and try to get infected. That risk just isn't worth taking as people, even young healthy people, can get very, very sick. We want to simply stop infections from happening, full-stop, to get this virus under control and prevent it from mutating further.

What if the response to that is "vaccinated people can transmit the virus, too," a fact now confirmed?

They can, but

we have evidence showing that vaccinated people are less likely to both get infected and to transmit the virus, and may spread the virus for a shorter time.

Are antibody tests a reliable way for someone to assess their immunity to COVID-19?

There are a couple things that are flawed about that. First, antibody levels wane over time; that happens naturally. Second, these tests don't capture the full picture. Antibodies are just one part of the equation. They're not primarily responsible for preventing severe disease once you're infected—that's the job of your memory immune response, which remembers the pathogen it saw before and gears up to control infection. Then there's the whole other arm of your immune system called T-cells, whose job is to recognize the virus in your body, identify cells infected with the virus, and destroy those cells.

The antibody tests are designed to diagnose whether you've had the infection recently. They're not designed to tell you how your immune system is going to respond to COVID-19, or how well your vaccines are going to work.

What other misconceptions about immunity do you want to clear up?

I want people to understand that vaccination-induced immunity, like natural immunity, doesn't necessarily protect you from getting

infected with COVID-19. The purpose of vaccinations is to prevent severe illness and death. So, yes, we're seeing some breakthrough infections among vaccinated people and will continue to, but that's expected and doesn't mean the vaccines are failing. Even with the delta variant, this is a success story because we're seeing vaccines for the most part do what they need to do.

Also, this topic of booster shots I think is a bit of a distraction right now. There's this idea out there that your immunity suddenly falls off a cliff at six or eight months. That's not what's happening. You still have that memory immune response, and that's why we're still seeing effectiveness against the delta variant.

The other thing I need to stress is that booster shots aren't going to stop delta. The only way we can do that is to have unvaccinated people get their initial vaccinations. That's the only way we're going to control not only delta but the emergence of other variants that could prolong or worsen this pandemic.

How long did it take from the time you got it to when you started feeling bad?

How long did it take from the time you got it to when you started feeling bad?

and gradually got worse as the day went on. severe body aches

and gradually got worse as the day went on. severe body aches  , cold sweats

, cold sweats