After he escaped prison, Emmett Bass spent 27 years on the run

Just like Robert Stackowitz, a Georgia prison escapee caught after 48 years, Bass was finally caught when he filed for social security benefits

By Shaun Raviv

October 6, 2016

Emmett Bass - Photograph by Kevin D. Liles

“I thought I was gonna get snatched up any time,” says Bass, 70, sitting in his nicely shaded backyard in Adair Park. He lives in a brown-and-white bungalow with long-term partner Mildred Shy and one of their two grown daughters. Bass looks up with foggy eyes and speaks through a mostly toothless mouth. He says he can laugh now about skipping out on the rest of his term. “I’m glad I got away,” he says. “What would I want to stay in prison for?”

This past May another longtime Georgia fugitive, Robert Stackowitz, was arrested in Connecticut 48 years after walking away from a Carroll County work detail. He’d been the getaway driver for two men who robbed an Atlanta home in 1966, holding the owner at gunpoint and tying him up. In 1968, two years into a 17-year sentence, Stackowitz found a ride to the Atlanta airport and flew to his home state, where he moved to a small town and started over under a new name, reportedly staying out of trouble until his recapture.

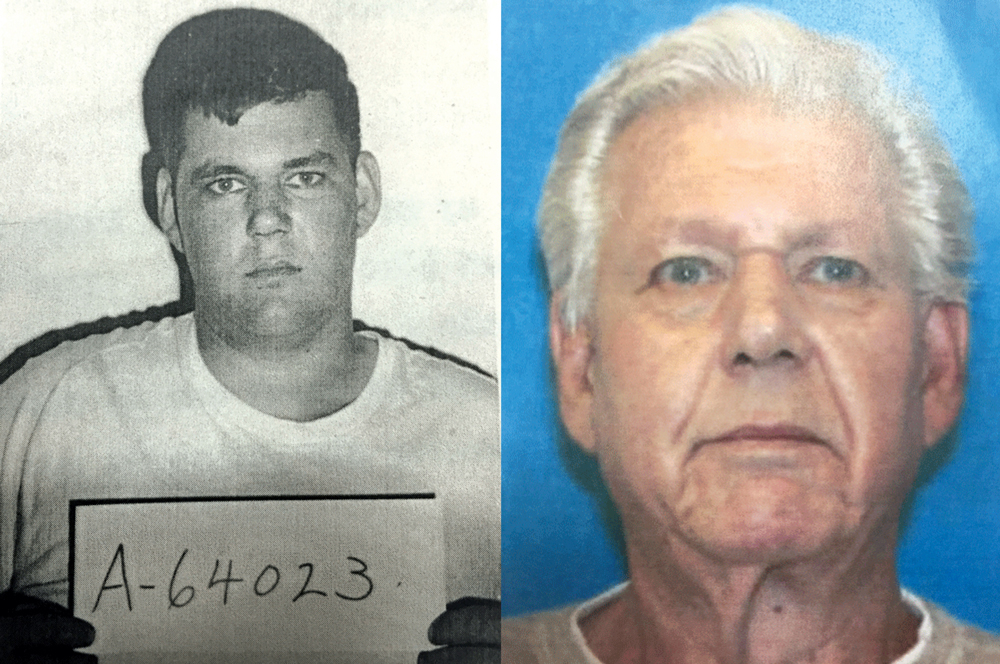

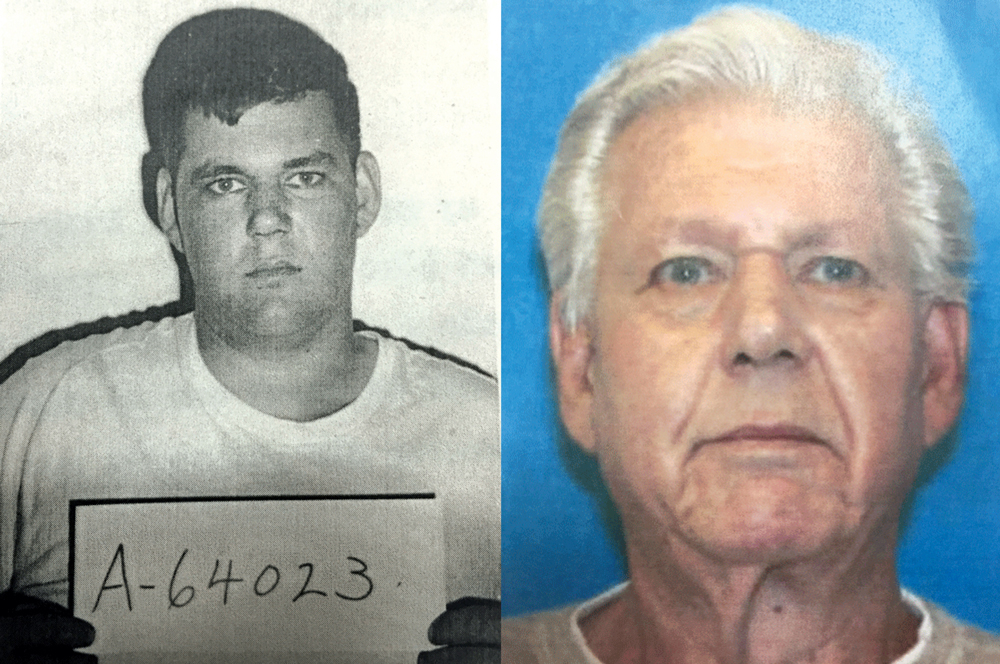

Robert Stackowitz—seen here in arrest photos from 1966 and 2016—spent 46 years on the lam after escaping from a prison work detail in Carroll County.

If the Georgia Corrections Department succeeds in extraditing Stackowitz—now 71 and suffering from bladder cancer—it might do well to refer to the Emmett Bass case in deciding what to do with him. Like Stackowitz, Bass escaped without much drama just a few years after being arrested. Bass, only 32 years old when he fled, also found his way to Atlanta, but unlike Stackowitz, he ended up staying.

After his conviction, Bass, who says he had no idea his “associate” was going to rob the store, was transferred around before landing at a prison in Griffin, where he’d grown up. When he woke up in the hay barn, he was wearing a striped prison outfit, so he traveled along ditches in the dark and steered clear of pedestrians and cars.

He went to his sister’s home to get a new set of clothes, but she told him to turn himself in. “Told her I ain’t going back,” Bass says. “They got to catch me and take me back ’cause I ain’t gonna give up after I went through all that crap.” He next went to a cousin, who let him in. He took a bath, changed his clothes, ate dinner, and in the morning another relative drove him to his mother’s house outside town to get some money. Then they headed north to Atlanta, where Bass rented a room in a house on the west side. “We were planning on going further,” he says, “but I got here and I just stayed.”

He went to work in construction—leveling basements, pushing wheelbarrows, laying bricks—and eventually had a somewhat normal life. The man who liked to gamble found a place to play spades at the nearby Harris Homes housing project. There, within a year of his escape, he met a future nurse named Mildred Shy. They moved to Adair Park, raised twin daughters and a son Shy had from a previous relationship, and have been together ever since.

After many years of smoking, Bass developed difficulty breathing. He was diabetic and had emphysema. By 2005 it had been more than two decades since he’d left the prison detail, and he hoped authorities had forgotten about him. Like Stackowitz, he applied for Social Security benefits because he couldn’t work. And like Stackowitz, that’s how he got caught. “I got greedy,” he says.

The day of his capture, Bass had been feeling pretty damn lucky. He was walking down his street with $2,000 in his pocket from hitting his lottery numbers the day before when a pickup pulled up next to him. A police officer got out and asked Bass for his ID. When he saw it, the officer said, “Damn, boy, we’ve been looking for you for 27 years!” Bass, then 59, no longer had the energy to run. The police took him home to get his diabetes medicine, put him in handcuffs, and took him to prison. “They put my ass in the truck,” Bass says, “and shot my ass straight to Jackson.”

Looking back on his 9,984 days as a fugitive, Bass says being on the run is just another way of serving time. “I had done that 15 years on the street,” he says. “I was looking over my shoulder all the time.” But in 1977, a few months before he escaped, a sentencing review panel had reduced his sentence to 10 years. And in 1978, Bass’s sentence was modified again—effectively cut in half because of good behavior. Had he stayed in prison, he likely would have served only two and a half more years. Instead, he spent 27 years being pursued, plus 10 months in jail after his recapture and another 20 months on parole.

Like Bass, Stackowitz managed to stay on the right side of the law after his escape. “You get the impression that he’s lived quietly and tried to enjoy life one day at a time,” says his lawyer, Norm Pattis, who is arguing that his client’s clean record over the past half century proves his rehabilitation. Stackowitz could find out by year’s end if he’ll be sent back to Georgia.

Bass feels like he got off pretty well in the end, surviving his return to prison and living free ever since.

“I thought I wasn’t gonna get out of there,” he says. He still likes to gamble, and even remembers his winning lottery numbers from the day before he was recaptured: 8-5-9. Every once in a while, he still hits his picks, he says. “Sometimes I get lucky, ya know?”

Editor’s note: In late September, after this story was written and published, the state of Georgia agreed not to seek extradition of Stackowitz, citing his precarious medical condition.

This article originally appeared in our October 2016 issue.

Just like Robert Stackowitz, a Georgia prison escapee caught after 48 years, Bass was finally caught when he filed for social security benefits

By Shaun Raviv

October 6, 2016

Emmett Bass - Photograph by Kevin D. Liles

Emmett Bass is a gambling man. In 1975 he and another man were arrested in Henry County for armed robbery of a package store. Bass was convicted and given a 15-year sentence. Three years later, on April 3, 1978, Bass was on a work detail near Highway 16 in Griffin when he went to relieve himself in the trees. Instead of returning to where his fellow inmates were cleaning ditches in the hot sun, he continued deeper into the woods. He found a hay barn, fell asleep, and by the time he woke up it was night. It would be 27 years before the police finally caught up with him.“I thought I was gonna get snatched up any time,” says Bass, 70, sitting in his nicely shaded backyard in Adair Park. He lives in a brown-and-white bungalow with long-term partner Mildred Shy and one of their two grown daughters. Bass looks up with foggy eyes and speaks through a mostly toothless mouth. He says he can laugh now about skipping out on the rest of his term. “I’m glad I got away,” he says. “What would I want to stay in prison for?”

This past May another longtime Georgia fugitive, Robert Stackowitz, was arrested in Connecticut 48 years after walking away from a Carroll County work detail. He’d been the getaway driver for two men who robbed an Atlanta home in 1966, holding the owner at gunpoint and tying him up. In 1968, two years into a 17-year sentence, Stackowitz found a ride to the Atlanta airport and flew to his home state, where he moved to a small town and started over under a new name, reportedly staying out of trouble until his recapture.

Robert Stackowitz—seen here in arrest photos from 1966 and 2016—spent 46 years on the lam after escaping from a prison work detail in Carroll County.

If the Georgia Corrections Department succeeds in extraditing Stackowitz—now 71 and suffering from bladder cancer—it might do well to refer to the Emmett Bass case in deciding what to do with him. Like Stackowitz, Bass escaped without much drama just a few years after being arrested. Bass, only 32 years old when he fled, also found his way to Atlanta, but unlike Stackowitz, he ended up staying.

After his conviction, Bass, who says he had no idea his “associate” was going to rob the store, was transferred around before landing at a prison in Griffin, where he’d grown up. When he woke up in the hay barn, he was wearing a striped prison outfit, so he traveled along ditches in the dark and steered clear of pedestrians and cars.

He went to his sister’s home to get a new set of clothes, but she told him to turn himself in. “Told her I ain’t going back,” Bass says. “They got to catch me and take me back ’cause I ain’t gonna give up after I went through all that crap.” He next went to a cousin, who let him in. He took a bath, changed his clothes, ate dinner, and in the morning another relative drove him to his mother’s house outside town to get some money. Then they headed north to Atlanta, where Bass rented a room in a house on the west side. “We were planning on going further,” he says, “but I got here and I just stayed.”

He went to work in construction—leveling basements, pushing wheelbarrows, laying bricks—and eventually had a somewhat normal life. The man who liked to gamble found a place to play spades at the nearby Harris Homes housing project. There, within a year of his escape, he met a future nurse named Mildred Shy. They moved to Adair Park, raised twin daughters and a son Shy had from a previous relationship, and have been together ever since.

After many years of smoking, Bass developed difficulty breathing. He was diabetic and had emphysema. By 2005 it had been more than two decades since he’d left the prison detail, and he hoped authorities had forgotten about him. Like Stackowitz, he applied for Social Security benefits because he couldn’t work. And like Stackowitz, that’s how he got caught. “I got greedy,” he says.

The day of his capture, Bass had been feeling pretty damn lucky. He was walking down his street with $2,000 in his pocket from hitting his lottery numbers the day before when a pickup pulled up next to him. A police officer got out and asked Bass for his ID. When he saw it, the officer said, “Damn, boy, we’ve been looking for you for 27 years!” Bass, then 59, no longer had the energy to run. The police took him home to get his diabetes medicine, put him in handcuffs, and took him to prison. “They put my ass in the truck,” Bass says, “and shot my ass straight to Jackson.”

Looking back on his 9,984 days as a fugitive, Bass says being on the run is just another way of serving time. “I had done that 15 years on the street,” he says. “I was looking over my shoulder all the time.” But in 1977, a few months before he escaped, a sentencing review panel had reduced his sentence to 10 years. And in 1978, Bass’s sentence was modified again—effectively cut in half because of good behavior. Had he stayed in prison, he likely would have served only two and a half more years. Instead, he spent 27 years being pursued, plus 10 months in jail after his recapture and another 20 months on parole.

Like Bass, Stackowitz managed to stay on the right side of the law after his escape. “You get the impression that he’s lived quietly and tried to enjoy life one day at a time,” says his lawyer, Norm Pattis, who is arguing that his client’s clean record over the past half century proves his rehabilitation. Stackowitz could find out by year’s end if he’ll be sent back to Georgia.

Bass feels like he got off pretty well in the end, surviving his return to prison and living free ever since.

“I thought I wasn’t gonna get out of there,” he says. He still likes to gamble, and even remembers his winning lottery numbers from the day before he was recaptured: 8-5-9. Every once in a while, he still hits his picks, he says. “Sometimes I get lucky, ya know?”

Editor’s note: In late September, after this story was written and published, the state of Georgia agreed not to seek extradition of Stackowitz, citing his precarious medical condition.

This article originally appeared in our October 2016 issue.

dude really thought they forgot. Like the feds just said "u know what its been 27 years fukk this ninja

dude really thought they forgot. Like the feds just said "u know what its been 27 years fukk this ninja  u know what we dont want u back! he probably dead anyway

u know what we dont want u back! he probably dead anyway