Some years ago here in Brazil they made a novel with this kuduro dance.

The theme quickly reached the top spots on local hit charts

I know lol, I remember that.

Some years ago here in Brazil they made a novel with this kuduro dance.

The theme quickly reached the top spots on local hit charts

Is this diasporic influence?

A collection of mostly African artists who have created their own hybrid of their traditional music and American Blues, R&B and Rock.

The Rough Guide To Desert Blues is a world music compilation album originally released in 2010. Desert blues refers to the music of the Mandinka and related nomad groups of the Sahara, who perform a style of music considered the root of the American Blues genre. This was first popularized in the West by Ali Farka Touré and has more recently been carried by a new wave of artists such as Tinariwen.[1]

Part of the World Music Network Rough Guides series, the album contains two discs: an overview of the genre on Disc One, and a "bonus" Disc Two highlighting Etran Finatawa. Disc One features nine Malian tracks, two Sahrawi, and one each from Mauritania and Niger. The compilation was produced by Phil Stanton, co-founder of the World Music Network.[2][3]

The late lamented African Bluesman Ali Farka Touré is still celebrated as one of the pioneering figures of West African music. It was he who took the traditional music of Mali, the music of the Jeliya and the Kora, and applied it to the guitar, to create something which resembled the blues of America’s Mississippi delta. Touré’s music has been credited with bringing to light the spiritual and ancestral connection between the music of the West African hinterland and the music of the delta bluesmen, which traced its lineage to the songs brought over by African slaves on the Middle Passage. Touré’s Mali Blues reunified these two distinct branches of ‘African Music’, prompting Martin Scorsese to famously comment that Touré’s music contained the ’DNA of the Blues’.

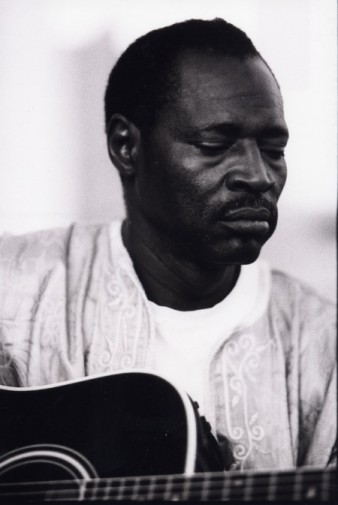

Ali Farka Touré | Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

Ali Farka Touré was also one of the first African musicians to gain a degree of worldwide fame and was a part of the forefront of the so-called ‘World Music’ movement, which came to prominence in the late 1970s and 80s. His popularity both within and beyond the borders of Mali transformed Western perceptions of African music and culture. Many artists were able to follow in his footsteps and gain critical exposure beyond West Africa, such as Habib Koité and Salif Keita, who have both gained a widespread following in the West. Touré’s cultural and social significance for the people of Mali is underlined in the documentary A Visit to Ali Farka Touré in which we see Touré engaging in social programs, as well as playing music with people from the various tribes and ethnic groups of Mali.

The country’s growing status as a cultural destination are reflected in the success of the Festival in the Desert, which is held there every January and is now in its eleventh year. Past performers at the festival have included such icons of West African music as Ali Farka Touré, Salif Keita and the Tuareg band Tinariwen. Despite having to change location in 2010, from the desert regions of Mali to a location closer to Timbuktu, the festival continues to grow in international prominence, and with it Malian music, as more artists come out from the shadow of Ali Farka Touré and develop their own versions of Malian music. As with Touré, whose music both embraced West African tradition and transcended it, artists such as Amadou & Mariam and Touré’s son Vieux Farka Touré, are reinventing West African music and bringing it to new audiences all over the world.

Ali Farka Toure was born in 1939 in Gourmararusse (in the Timbuktu region), Mali, into the noble Sorhai family. Being of noble birth, he should never have taken up music. His family disapproved because the musician profession is normally inherited in Malian society and the right to play belongs to the musician families. However, being a man of determination and independence, once he decided to take up music, there was no stopping him.

Ali Farka Toure took up the guitar at the age of ten, but it wasn’t until about age 17 that he really got a handle on the instrument. In 1950 he began playing the gurkel, a single string African guitar that he chose because of its power to draw out the spirits. He also taught himself the njarka, a single string fiddle that was a popular part of his performances.

Then in 1956, Ali Farka Toure saw a performance by the great Guinean guitarist Keita Fodeba in Bamako. He was so moved that he decided then and there to become a guitarist. Teaching himself, Alila Farka Toure adapted traditional songs using the techniques he had learned on the gurkel.

During a visit to Bamako in the late 1960’s, artists such as Ray Charles, Otis Redding and most importantly John Lee Hooker introduced Ali Farka Toure to African-American music. At first, he thought that Hooker was playing Malian music, but then realized that this music coming from the United States of America had deep African roots.

Ali Farka Toure was also inspired by Hooker’s strength as a performer and began to incorporate elements into his own playing. During those years Ali Farka Toure composed, sang and performed with the famous Troupe 117, a group created by the Malian government after the country’s independence.

Ali Farka Toure trained as a sound engineer, a profession he practiced until 1980, when he had saved enough money to become a farmer, which is what he was until he died.

Ali Farka Toure – Photo by Thomas Dorn

[...] This style probably arose around 1800 on the island of Boa Vista. Originally the morna was only instrumental and played much faster, inspired by the lundu, which probably originated with Bantu slaves from Angola who brought their music to Cape Verde. Under the influence of other styles, especially the Brazilian modinha, the morna was slowed down and poetic lyrics were added. This poetry revolves around the feeling of saudade, a nostalgic combination of homesickness and lost love but yet hope for a better future. In the early 20th century, journalist Eugénio Tavares of the island Brava brought the morna to increased prominence and gave it its lyrical content. Tavares was a lover of the fado, which reveals a link to this Portuguese genre. In the first half of the 20th century, Francisco Xavier da Cruz (better known as B.Leza) and Luis Rendal of the island São Vicente added the influences of the Brazilian choro and samba.

In the 1930s and the 1940s, the morna gained special characteristics in São Vicente. The Brava style was much appreciated and cultivated in all Cape Verde by that time (there are records about E. Tavares being received in apotheosis in S. Vicente island and even the Barlavento composers wrote in Sotavento Creole, probably because the maintenance of the unstressed vowels in Sotavento Creoles gave more musicality). But specific conditions in S. Vicente such as the cosmopolitanism and openness to foreign influences brought some enrichment to the morna.

One of the main people responsible for this enrichment was the composer Francisco Xavier da Cruz (a.k.a. B.Leza) who under Brazilian music influence introduced the so-called passing chords, popularly known as “meio-tom brasileiro” (Brazilian half-tone) in Cape Verde. Thanks to these passing chords, the harmonic structure of the morna was not restrained to the cycle of fifths, but incorporated other chords that made the smooth transition to the main ones.

That sahel aa connection is interesting

You rarely hear about it irl tho

I watched some independent film showing that. I also read an article where some Nigerians there said that because of Afro beat it's the first time they are proud of their heritage. I'm sorry, but Nigerian Brits have always been corny to me. Even my uncles back home clown them. One of them said "I'm glad your father raised you in the US. You're not like the one to come back from The UK. Wearing shirts and ties, don't know how to do anything."

Not to derail the thread, it's known/talked about but it's a combination of associating all "african" music with drums and for most aframs, "blues" is a music of the past outside of a few regions of the usa like mississippi.

British Nigerians are so corny. I can't believe the levels they grew up being ashamed of their heritage in the UK

Not to say that it was easy here if United States, but it was always a lot more accepted here than over there

Gang leaders brehWrong, British Nigerians are the trendsetters in the uk, since the 90's

All the gang leaders in the Uk were either Nigerian or Jamaican, in the worst areas like Peckham, Deptford, Hackney so whats there to be ashamed off?

The name "bongo flava" is a corruption of "bongo flavour", where "bongo" is the plural form of the Swahili word ubongo, meaning "brain", and is a common nickname used to refer to Dar es Salaam, the city where the genre originated. In the bongo flava, the metaphor of "brains" may additionally refer to the cunning and street smarts of the mselah [...]

The term "bongo flava" was coined and first mentioned in 1996 by Radio One's 99.6 FM (one of the first private radio stations in Tanzania) Radio DJ Mike Mhagama who was trying to differentiate between American R&B and hip hop music through his popular radio show known as 'DJ Show' with that of local youngsters music that didn't have, at that time, an identity of its own. DJ Show was the first radio show that accepted young Tanzanian musicians influenced by American music to express themselves through singing and rapping. He said on air, "After listening to "R&B Flava" titled 'No Diggity' from the United States, here comes "Bongo Flava" from Unique Sisters, one of our own." After he said that on the show, the term "Bongo Flava" stuck.

Starting from the 1980s, liberalization politics have caused a profound transformation of cultural production in Tanzania. The privatization of media along with new techniques of production and distribution have facilitated the emergence of a new music scene, called Bongo Flava, as well as a flourishing market of video films in Swahili.

Bongo flava is a Tanzanian Hip Hop genre that originated in the mid-1990s in the Dar es Salaam area. Apart from being rooted in popular styles of American hip hop, bongo flava is influenced by various other genres including Rhythm & Blues, Afrobeat and Dancehall, as well as native Tanzanian music styles such as Taarab and Muziki wa dansi.

Bongo Flava, as Tanzanian hip hop music is known, has evolved from being a genre of outlaws into the most-loved source of entertainment. It has won over a sceptical older generation.

Bongo Flava is now the most popular musical style among locals. Christina Bella, A.Y, David Genz, Diamond Platnumz, Dully Sykes, Mr. II (who is said to be the pioneer of the genre) and Vanessa Mdee, are among the most prominent names.

Outside its historical home of Tanzania, Bongo Flava has become popular in neighbouring countries such as Kenya and Uganda.

The music has even found a home outside Africa with the most popular artistes in the genre addressing Western markets. And Bongo Radio, the self-proclaimed “best internet station for Bongo Flava”, is based in Chicago, Illinois in the US.

Kwaito

is a music genre that emerged in Johannesburg, South Africa, during the 1990s. It is a variant of house music featuring the use of African sounds and samples. Typically at a slower tempo range than other styles of house music, Kwaito often contains catchy melodic and percussive loop samples, deep bass lines, and vocals. Although bearing similarities to hip hop music, a distinctive feature of Kwaito is the manner in which the lyrics are sung, rapped and shouted. American producer Diplo has described Kwaito as "slowed-down garage music," most popular among the black youth of South Africa.