IllmaticDelta

Veteran

wouldn’t that one ... African American if One was born in America but families were from Liberia?

??

wouldn’t that one ... African American if One was born in America but families were from Liberia?

At the end of the day nothing is consistent when it comes to defining Who Americo Liberians when it comes to the Semantics people want to play. At the end of the day they were the descendants of Slaves anything else is a personal problem for other peoples agendas lol.

Strangely enough, the one-drop rule was not made law until the early 20th century. This was decades after the Civil War, emancipation, and the Reconstruction era. It followed restoration of white supremacy in the South and the passage of Jim Crow racial segregation laws. In the 20th century, it was also associated with the rise of eugenics and ideas of racial purity.[citation needed] From the late 1870s on, white Democrats regained political power in the former Confederate states and passed racial segregation laws controlling public facilities, and laws and constitutions from 1890 to 1910 to achieve disfranchisement of most blacks. Many poor whites were also disfranchised in these years, by changes to voter registration rules that worked against them, such as literacy tests, longer residency requirements and poll taxes.

Jim Crow laws reached their greatest influence during the decades from 1910 to 1930. Among them were hypodescent laws, defining as black anyone with any black ancestry, or with a very small portion of black ancestry.[3] Tennessee adopted such a "one-drop" statute in 1910, and Louisiana soon followed. Then Texas and Arkansas in 1911, Mississippi in 1917, North Carolina in 1923, Virginia in 1924, Alabama and Georgia in 1927, and Oklahoma in 1931. During this same period, Florida, Indiana, Kentucky, Maryland, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, and Utah retained their old "blood fraction" statutes de jure, but amended these fractions (one-sixteenth, one-thirty-second) to be equivalent to one-drop de facto.[18]

Before 1930, individuals of visible mixed European and African ancestry were usually classed as mulatto, or sometimes as black and sometimes as white, depending on appearance. Previously, most states had limited trying to define ancestry before "the fourth degree" (great-great-grandparents). But, in 1930, due to lobbying by southern legislators, the Census Bureau stopped using the classification of mulatto. Documentation of the long social recognition of mixed-race people was lost, and they were classified only as black or white.

Douglass considered himself to be neither White nor Black, but both. His multiracial self-identity showed in his first autobiography. Introducing his father in Narrative, Douglass wrote, “My father was a white man.” In this text, his mother was a stranger whom he had never seen in daylight, he could not picture her face, and he was unmoved by news of her death.4 Not only did Douglass adopt a fictional Scottish hero’s name, he emphasized his (perhaps imagined) Scots descent through his father. When visiting Great Britain in 1845-47, Douglass extended his stay in Scotland. He immersed himself in Scottish music and ballads, which he played on the violin for the rest of his life. Having plunged into a Scottish ethnic identity, Douglass wrote to his (then) friend, William Lloyd Garrison, “If I should meet you now, amid the free hills of old Scotland, where the ancient ‘black Douglass’ [sic] once met his foes… you would see a great change in me!”5 Upon arriving in Nantucket, Douglass hoped to represent a blending of both endogamous groups, a man who was half-White and half-Black:

Young, ardent, and hopeful, I entered upon this new life in the full gush of unsuspecting enthusiasm. The cause was good, the men engaged in it were good, the means to attain its triumph, good…. For a time, I was made to forget that my skin was dark and my hair crisped.6

But acceptance by White society was out of reach for Douglass. He discovered that, in the North, there was no such thing as a man who was half-Black. White ships’ caulkers in New Bedford denied him a chance to work at his craft because in their eyes he was all Black.7 When he joined the Garrisonians on a boat to an abolitionist convention in Nantucket, and a squabble broke out because the White abolitionists demanded that the Black abolitionists take lesser accommodations, Douglass found himself classified as Black by his friends. Later in Nantucket, Douglass so impressed the Garrisonians with his public speaking that abolitionist Edmund Quincy exchanged reports with others that Douglass was an articulate public speaker, “for a ******.”8 Repeatedly, Douglass tried to present himself as an intermediary between America’s two endogamous groups. But the Garrisonians made it clear that he was expected to present himself as nothing more than an intelligent “Negro.” He was told to talk only about the evils of slavery and ordered to stop talking about the endogamous color line. “Give us the facts [about being a slave]. We will take care of the [racial] philosophy.” They also ordered him to “leave a little plantation speech” in his accent.9 In their own words, they wanted to display a smart “******,” but not too smart.

Douglass’s cruelest discovery came after he broke with the Garrisonians and went out on his own. Abolitionist friends of both endogamous groups had warned him that there was nothing personal in how Garrison had used him. The public did not want an intermediary; they wanted an articulate Black. Douglass soon discovered that his friends were right. His newspaper, The North Star,failed to sell because it had no market; White Yankees wanted to read White publications and Black Yankees wanted to read Black ones. Indeed, Black political leaders resented Douglass’s distancing himself from Black ethno-political society. There was no room in Massachusetts for a man who straddled the color line.

Douglass dutifully reinvented himself. He applied himself to learning Black Yankee culture. “He began to build a closer relationship with… Negro leaders and with the Negro people themselves, to examine the whole range of Negro problems, and to pry into every facet of discrimination.”10 Eight months later, The North Star’s circulation was soaring and Black leader James McCune Smith wrote to Black activist Gerrit Smith:

You will be surprised to hear me say that only since his Editorial career has he seen to become a colored man! I have read his paper very carefully and find phrase after phrase develop itself as in one newly born among us.11

From that day on, Douglass never looked back. The public wanted him to be hyper-Black and so hyper-Black he became. His later autobiographies reveal the change.12 Narrative (1845) says that his “father was a white man,” My Bondage and My Freedom (1854) says that his father “was shrouded in mystery” and “nearly white,” and The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (1882-1892) says flatly, “of my father I know nothing.”13 Narrative says that his mother was a stranger whose death did not affect him, and Bondage and Freedom reports that he was “deeply attached to her,” Life and Times says that “her image is ineffably stamped upon my memory,” and describes her death with “great poignancy and sorrow.”14

And yet, although he donned a public persona of extreme Blackness, he continued to see himself as half White Scottish in his private life. When he eventually married Helen Pitts, a woman of the White endogamous group, even close friends were bothered by the mismatch between the public and private Douglasses.15 In a speech in 1886 Jacksonville, Florida, Douglass justified his intermarriage on the grounds of his own multiracial self-identity. According to James Weldon Johnson:

Douglass spoke, and moved a large audience of white and colored people by his supreme eloquence. … Douglass was speaking in the far South, but he spoke without fear or reservation. One statement in particular that he made, I now wonder if any Negro speaker today, under the same circumstances, would dare to make, and, if he did, what the public reaction would be; Douglass, in reply to the current criticisms regarding his second marriage, said, “In my first marriage I paid my compliments to my mother’s race; in my second marriage I paid my compliments to the race of my father.”16

* * * * *

The clash between how Douglass saw himself in 1838 and the public persona that he was forced to portray, was due to the presence of African-American ethnicity in the North.17 Free citizens of part-African ancestry in the South, especially in the lower South, lacked the sense of common tradition associated with ethnic self-identity. This essay traces the emergence of African-American ethnicity and the subsequent evolution of the color line in five topics: Origins of African-American Ethnicity explains how the imposition of a unique endogamous color line eventually led to the synthesis of a unique ethno-cultural community in the Jacksonian Northeast. African-American Ethnic Traits outlines the customs of the Black Yankee ethnic group to show that they gave birth to many of today’s Black traditions. The Integration versus Separatism Pendulum introduces a debate that has occupied Black political leaders since colonial times. The Color Line in the North contrasts the harsh enforcement of the intermarriage barrier in the free states with the more permeable systems of the lower South (as presented in the preceding three essays). The National Color Line’s Rise and Fall concludes this section on the endogamous color line by presenting two graphs. The first shows that which side of the endogamous color line you were on was most hotly contested in U.S. courts between 1840 and 1869. The second shows that the color line grew abruptly stronger during Reconstruction, was at its harshest during Jim Crow, and began to recover only around 1980.

black yankess(northern free people of color) were around at the time of the people who left to liberia. Black Yankees were the ones who were against it.

African America’s First Protest Meeting: Black Philadelphians Reject the American Colonization Society Plans for Their Resettlem

African America’s First Protest Meeting: Black Philadelphians Reject the American Colonization Society Plans for Their Resettlem | The Black Past: Remembered and Reclaimed

brah, I went there for 2 weeks I had to come back. I cannot see myself living there. Nothing to do, people always looking for a come up, your cousin always fukking up your money (we told dude to go to the nearest town to go wash our truck we went to another one, hit some dude on that was riding his bike and got our truck stuck in the mud. Had to pay 7 people to take it out) and police and other government officials looking to fine you with paper work to run your business over there. Man my dad and I almost threw hands with the police. This was last year. But Back in 2001 when I went there in 6th grade man my dad was gonna fight soldiers that were carrying ak-47 cause they kept asking us to give them money at every check point. I remember there were bullet holes on people houses including my cousin From the civil war.

This makes no sense as none of you on this site lived through Jim Crow or reconstruction, which by logic would discount you as being Afram, which is the logic you're applying hereNo one is even claiming or arguing that. I don't know how you brought that up.

Point is Americo-Liberians were for the most are not the same as modern day AAs. Especially when people try to say AAs ruined Liberia. Americo-Liberians for the most part were not even enslaved but freed blacks. And so their experience was different from the average AA.

This makes no sense as none of you on this site lived through Jim Crow or reconstruction, which by logic would discount you as being Afram, which is the logic you're applying here

So we could say you, yourself and your children's children are different since you never lived through this. Those free people of colour where Ados just like you and probably even moreso as they where born during when slavery.Our ancestors -- meaning out direct family members lived through Jim Crow and Reconstruction and enslavement. Some of our families members are still living who lived through Jim Crow - as it didn't end till the 1960's.

old thread but

Yes and no. The light ones were free people of color who lived in the south, decades before the one drop rule and jim crowism. The color & class lines between afrodescendants were more broken up/less unified in the south at that time

The Afram identity that we know today (blurring of complexion and admx) is a NORTHERN AFRAM creation, not a Southern one.

which I fully explain below

1st, contrary to popular belief: WHITE americans didn't invent one-droppism. It wasn't even a law by white people until the 1910's

It was created by Northern USA, Aframs.

basically;free people of color which usually described light skinned people;negro which meant darker/unmixed blacks, would became: colored american (this would later become afro-american and/or black), to encompass all shades/mixes of afro-descendants

this exact process played out when Frederick Douglas who was from the South, went North and encountered; "Black Yankees"

Essays on the U.S. Color Line » Blog Archive » The Color Line Created African-American Ethnicity in the North

..........this is why some of those lighter skinned ones exported from the American South & imported to LIberia/followed a colorline/caste system that's unlike 2 tier caste system that MODERN AFRAM IDENTITY was born in.

If you want to know how early FREE PEOPLE OF COLOR ( afro-europeans/triracials) in the American South saw things, look no further than all the FPOC "Indian" groups scattered around the South

........most of the of the light skinned people that went to Liberia were from Virginia, Maryland, and the Carolinas; the same places that had these early, more fluid colorlines

So we could say you, yourself and your children's children are different since you never lived through this. Those free people of colour where Ados just like you and probably even moreso as they where born during when slavery.

Also how would you classify descendants of free people of colour, who lived through Jim Crow, Reconstruction, Civil Rights. How about those whose ancestors escaped but lived through it (i.e Harriet Tubman) and thus born free, are their descendants not AA to.

This makes no sense as none of you on this site lived through Jim Crow or reconstruction, which by logic would discount you as being Afram, which is the logic you're applying here

So we could say you, yourself and your children's children are different since you never lived through this. Those free people of colour where Ados just like you and probably even moreso as they where born during when slavery.

Also how would you classify descendants of free people of colour, who lived through Jim Crow, Reconstruction, Civil Rights. How about those whose ancestors escaped but lived through it (i.e Harriet Tubman) and thus born free, are their descendants not AA to.

The modern AfroAmerican indentity was fully crystallized THROUGH & AFTER Jim Crow & Reconstruction. W/o those 2 factors (which ADOS who went to Liberia never faced), ADOS would have never fully became "black" in the way that bypassed phenotypes

.

.

.

^^^^that's fully formed ADOS identity who lived/came through Jim Crowism

.

.

On the flip side

They would still be doing weird shyt like what the ADOS imported to Liberia based on PRE-JIM CROW/ONE DROP RULE slave system dynamic, experiences

Even darker skinned Americo-Liberians (ADOS) suffered to a degree

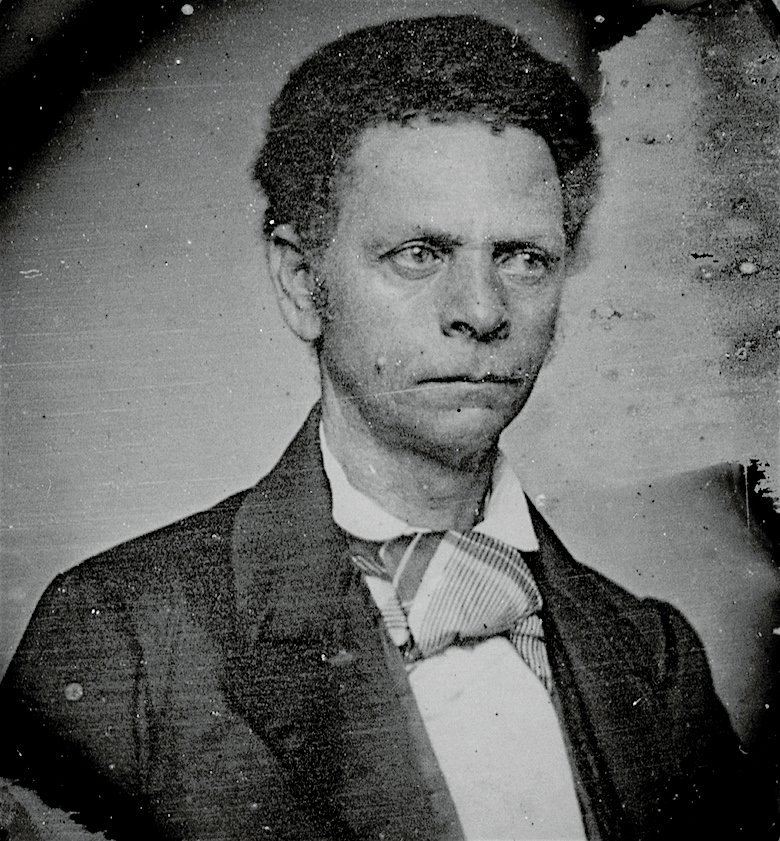

Edward Roye was a dark skinned Americo-Liberian

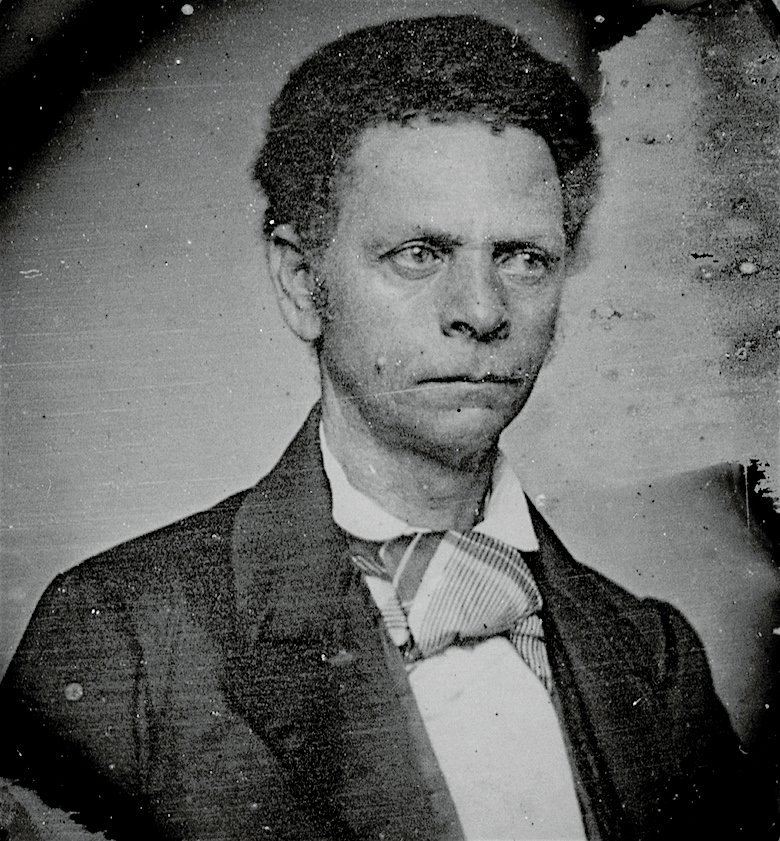

Joseph Roberts was a light skinned Americo-Liberian from the South

.

.

.

more context

.

that's pretty much how pre-Jim Crow/One Drop, South operated in the USA

ADOS who went to Liberia came up in that dynamic; the ADOS who lived through Jim Crow, birthed the MODERN ADOS identity

Thomas Sheridan (ca. 1787-1864) was an emancipated mulatto carpenter active in Bladen County during the antebellum period, whose only documented building is the Brown Marsh Presbyterian Church (1828) in that county.

Thomas Sheridan’s family background illustrates the complexities of race and status in his era. Probably born in Bladen County, he may have been the son of Nancy Sheridan (a woman of color who was emancipated after his birth) and Joseph R. Gautier, a wealthy Bladen County planter and merchant of French Huguenot background. Gautier, who was frequently listed among the leading men of the Cape Fear region, was a political figure in Elizabethtown, a state senator (1791), and an early supporter of the University of North Carolina noted for having left his library of some 100 volumes (mostly in French) to the university’s library. Gautier was the owner of several slaves, including Thomas Sheridan and his brother Louis Sheridan, and probably Nancy Sheridan. Circumstantial evidence also indicates that Joseph Gautier and Nancy Sheridan had a long-term domestic relationship: many white men who had such relationships with their enslaved women often freed their enslaved family members and provided for them (although emancipation became increasingly difficult in the early and mid-19th century).

Louis Sheridan (ca. 1793-1844), probably Thomas’s brother or half-brother, gained a good education and became an important merchant and large property owner in Elizabethtown with business connections throughout the state and even the nation. He owned as many as sixteen slaves. He also acquired many town lots in Elizabethtown, including those he sold as sites for the courthouse and for the Presbyterian and Methodist churches. Probably because of his father’s position and connections, Sheridan was aided by former governor John Owen and other leading men of the region and traveled widely for business to Philadelphia, New York, and elsewhere. Although he had initially opposed colonization, after the state placed tighter restrictions on free people of color in the 1830s, Louis Sheridan joined the Liberian colonization movement. He sold his slaves and moved with his family to Liberia in 1837, where he found a situation far less rosy than he anticipated and wrote (often negative) reports back to the United States. He remained there nevertheless and died there in 1844.

Sheridan occupied one of the best houses in Elizabethtown, and his household in 1829 was composed of himself, aged twenty-six, eight male and four female slaves, and three free blacks. In 1830 the household consisted of twenty-three persons including sixteen slaves, five free blacks, one of whom is said to have been his mother, and two white males under the age of thirty, who may have been clerks in his store since many of his customers were white. As a slave owner, Sheridan had the reputation of being "a severe master."

Although he had friends of both races, Sheridan had difficulty in finding his place in society. Until the liberties of free blacks in America began to be restricted following a slave insurrection in Virginia in 1831, he opposed the colonization of blacks in Africa. Legislative action and changes in the North Carolina Constitution in 1835, however, led him to yield to the suggestion of agents of the American Colonization Society that he move to Africa. They observed that "[f]or energy of mind, firmness of purpose and a variety of practical knowledge, Sheridan has no superior."

In 1836 Sheridan decided that he and "39 other persons of my family" would begin plans to move. He freed his own slaves in 1837 and sailed for Liberia two days before Christmas, taking with him between $15,000 to $20,000, a large quantity of lumber, and thirty tons of merchandise to be sold there. He had refused to take a ship from Norfolk and agreed to sail only when a ship was made available in Wilmington. He also insisted that ample good food and drinking water be provided for the voyage as well as comfortable accommodations for his family.

These people were definitely representative of the One-Drop rule.

Paul Cuffee (1759–1817) was a mixed-race, successful Quaker ship owner, and activist descended from Ashanti and Wampanoagparents. He advocated settling freed American slaves in Africa and gained support from the British government, free black leaders in the United States, and members of Congress to take emigrants to the British colony of Sierra Leone. Cuffee was an early advocate of settling freed blacks in Africa and he gained support from black leaders and members of the U.S. Congress for an emigration plan.[14] In 1815 he financed a trip and the following year,[15] in 1816, Cuffee took 38 American blacks to Freetown, Sierra Leone; other voyages were precluded by his death in 1817. By reaching a large audience with his pro-colonization arguments and practical example, Cuffee laid the groundwork for the American Colonization Society.[16]

Louis Sheridan, farmer, free black merchant, and Liberian official, was probably the Louis Sheridan mentioned in the 1800 will of Joseph R. Gautier (d. 15 May 1807), Elizabethtown merchant, as the son of Nancy Sheridan, "my emancipated black woman" to whom he left "my plantation at the Marsh." Louis obtained a good education and engaged in extensive mercantile operations. Although he was a mulatto with a fair complexion, he was recorded as white in the Bladen County censuses for 1810, 1820, and 1830. He was aided in business by John Owen, former governor, and other white men of the Lower Cape Fear who gave him letters of introduction. Sheridan made business trips to nearby Wilmington as well as to Philadelphia, New York, and elsewhere, sometimes making purchases of goods valued in excess of $12,000. As a young man he preached for a brief time and also subscribed to and served as an agent for two black newspapers.

They were not slaves.....

This goes further to showcase "Mulattos" who represented majority of "Free People of Color" did not see themselves as "Black" - hence couldn't be listed as AA.

Source: Another America: The Story of Liberia and the Former Slaves Who Ruled It