Frances Negron-Muntaner

yesterday9 min read

Why Do Americans Find Cuba Sexy — but Not Puerto Rico?

The history of why the American imagination treats two Caribbean islands very differently.

By Frances Negrón-Muntaner

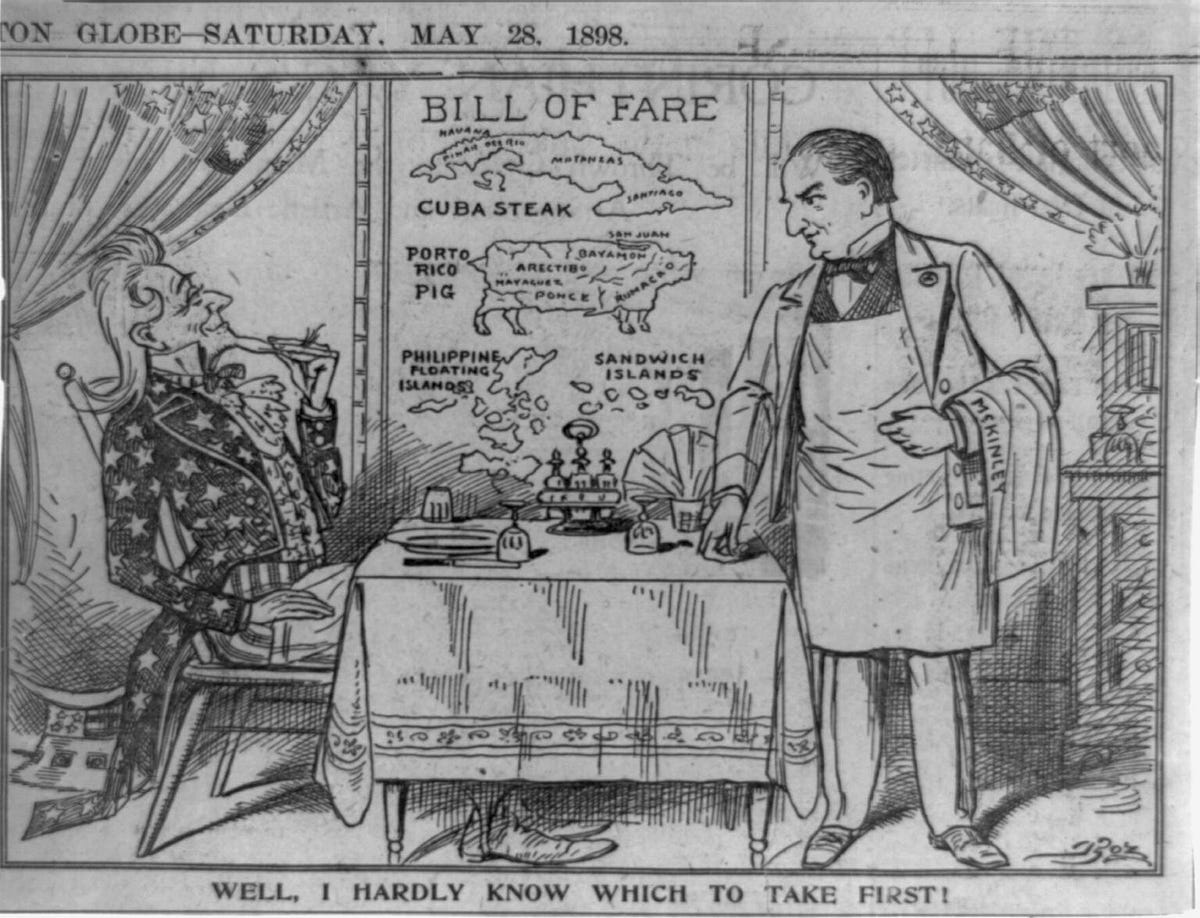

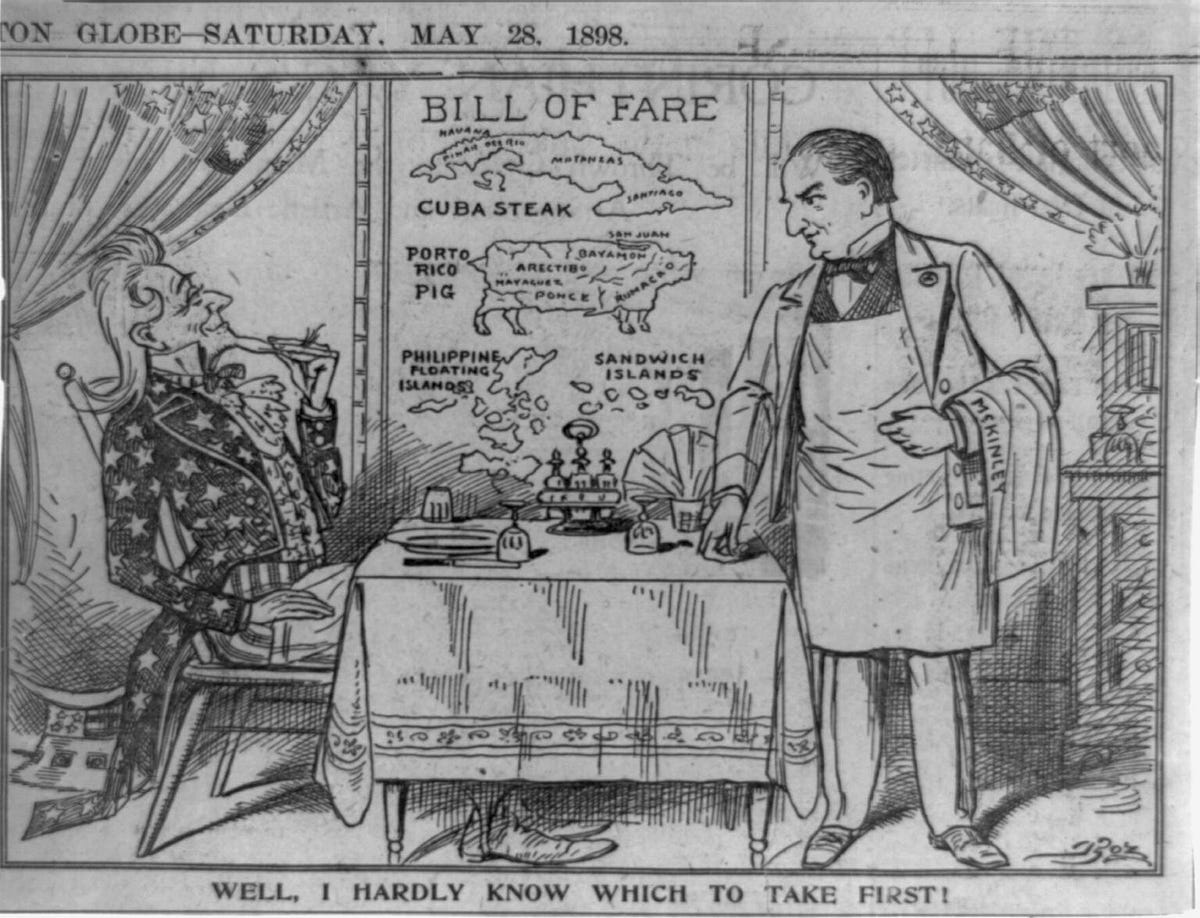

Cartoon in the Boston Globe, May 1898. (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

The editor of a leading publishing house was not moved by my impassioned pitch: to write a major English-language biography of Julia de Burgos, a Puerto Rican poet and national icon whose name or likeness can be found in dozens of murals, buildings, and street signs across Latino neighborhoods. To my proposal, he simply said: “Nah. It wouldn’t sell. The only Latin biography I’d publish is José Martí.”

“José Martí?” I repeated, incredulous. Certainly, the renowned Cuban poet and pro-independence hero merits not one but many biographies. The categorical tone of his reply, however, puzzled me: “Why only Martí?” The editor smiled: “Martí comes from a sexy country.” “But he’s not sexy,” I countered.

The double standard made little sense. Yet, it could be explained — and should. For how Americans view Cuba and Puerto Rico has both history and consequences, including now when the U.S. government just imposed a fiscal control board on Puerto Rico and Cuba warily embraces American investment.

Since the islands first entered the young republic’s field of vision in the 19th century, Cuba has always been the more attractive of the two. It was bigger. It was more elegant. But, above all, it was closer. In the American imagination, Cuba appeared as emotional boundary and vulnerable national border, an Achilles’ heel whose possession by another could bring about the destruction of the United States itself. In fact, the American fear that a different country than Spain would govern Cuba reached such heights that, between 1823 and 1897, the U.S. made no fewer than four attempts to purchase the island. To be in control of Cuba’s destiny grew into an obsession.

If Cuba is a colorful fantasy that lasts and lasts like a Life Savers lollipop, Puerto Rico is a nuisance, like a wad of gum stuck to the bottom of a shoe.

When the U.S. finally took up arms in the matter during the Spanish-American War of 1898, its fixation with Cuba intensified. Invoking libidinous and political fantasies, the press represented the island in numerous caricatures and narratives as a beautiful young woman or a starving mother, crying out for a savior who could rescue her from Spain. That Cuban pro-independence fighters were largely missing from the picture leaves little doubt that Uncle Sam was interested solely in saving Cuba — not Cubans.

Up until the U.S. readied to invade Puerto Rico, the island was hardly mentioned in the nation’s war coverage. Yet as the military campaign there advanced, references to Puerto Rico in the American press increased. Unlike with Cuba, however, the taking of “Porto Rico” is often described in cold imperial terms: Politicians and experts agreed on the island’s strategic advantages and business potential; they also assured readers that Puerto Rico was too small to be independent and would benefit from American guidance. Journalists likewise reported, in short articles underlining the island’s lack of importance, that it was Puerto Ricans and not Americans who were “excited” about the invasion.

Once in control of the islands after the 1898 Treaty of Paris, the U.S. imposed military governments in Cuba and Puerto Rico. In print, the Cuban belle morphed into a black boy who, similar to his Puerto Rican cousin, needed Uncle Sam to forever teach him the art of self-government. Nevertheless, whereas Americans saw themselves as superior to both Cubans and Puerto Ricans, the ethos of independence made them feel closer to Cubans. In the words of influential congressman Henry Teller, author of the amendment precluding the U.S. annexation of Cuba: “I don’t like the Puerto Rican. They are not fighters like the Cubans. They were under Spanish tyranny for centuries without showing enough manhood to oppose it. Such a race is unworthy of U.S. citizenship.”

The next step was as creative as it was crafty. While the desire to annex Cuba culminated in the American “concession” of independence in 1902, the U.S. viewed it as theirs. Puerto Rico, however, is legally possessed outright, even as the Supreme Court decided the island, like a superfluous accessory, belongs to — but is not part of — the U.S. Although the U.S. eventually extended citizenship to Puerto Rico’s residents in 1917, this formality had little to do with integration or civil rights. As colonial governor Arthur D. Yager put it, the U.S. citizenship of Puerto Ricans simply indicated that, “we have determined … the American flag will never be lowered in Puerto Rico.” Consequently, islanders entered the equivalent of political limbo: they could serve in the U.S. military but not vote for the president nor have a voting congressional representation.

By the 1920s, America’s attraction to Cuba eagerly returned to its primal idiom: sex. From the Roaring Twenties to the “lost decade” of the 1950s, Americans made Havana their go-to destination for the three Ds: dancing, drinking, and dealing. Puerto Rico, despite having spectacular beaches and a climate similar to the island next door, could boast only one luxury hotel, the Condado Vanderbilt, until 1949, when the Caribe Hilton was built — at the behest of the insular government. If Cuba was triple-D, Puerto Rico was triple-P: poor, puny, and passive. Americans remained hooked on Havana.

At least, until el mambo came to an end. Though the U.S.-Cuba affair was invariably tense, the Cuban Revolution of 1959 abruptly ended America’s romance, yet turned the island into a much more alluring girl. Again, Cuba became the forbidden fruit that must be re-acquired at all costs through invasions, embargoes, and assassination attempts — and no wonder: By 1958, Cuba was not just a popular adult amusement park for Americans. U.S. capital controlled a large portion of the island’s economy, including 90 percent of the electric and telephone industries, 83 percent of the railway commerce, and 43 percent of the sugar business.

Simultaneously, if the masculinity of young Cuban men-at-arms was a turnoff for the American political elite, it attracted leftist and minority intellectuals, who understood the revolution as a direct challenge to the racist and colonial policies of the U.S. at home and abroad. Even further, the revolution raised Cubans to the level of international sex symbols, models of how a small and poor nation could confront the most powerful military in the world and win. This development immediately affected Puerto Rico.

To counter the rise of Cuba rebelde as a sexy global brand, the U.S re-fashioned Puerto Rico as a plain but attractive alternative by offering corporate incentives and tax breaks. The new look is evident in a 1958 cover of Time magazine, featuring the island’s gray-haired governor Luis Muñoz Marín. Once more, Puerto Rico is sold in clinical terms, this time, as a laboratory “about democracy in Latin America.” According to the magazine, Puerto Rico demonstrates how good capitalism can be when Latin America embraces U.S. investment and rejects nationalism. Clinical or otherwise, the experiment soon lost funding and went into crisis. Not only did the ensuing Puerto Rican “economic miracle” last less than two decades, it required the exportation of over 700,000 Caribbean souls to cities such as New York to serve as cheap and expendable labor.

The motivation now is less to restore the border with Cuba than to recover lost time and re-conquer the last nearby market not deeply penetrated by American capital.

Ironically, even though many New Yorkers regarded Puerto Rican migrants as “tropical scum,” their origin “somewhere down there,” made it possible for a handful to be assimilated through the Latin Lover and sexy spitfire stereotypes. After 1959, the situation for Cubans fleeing to the U.S. is reversed: Although they received a warmer welcome, for Americans, the heat stayed behind. Whether considered model minorities as the first wave of exiles or riffraff after the 1980 Mariel boatlift, Cubans in America rarely earn the “most sexy” title–with the exception of those who work really hard at it like Pitbull. As always, the crown of sexy is reserved collectively for those who remain or live in Cuba — and Che, of course.

It is, then, not surprising that, in the last two years, as relations between the U.S. and Cuba have “thawed” and President Barack Obama became the first American president to visit since 1928, sexual rhetoric has returned as a vital component of the rapprochement, foreshadowing conflicts to come. In the first few months of 2015 alone, dozens of influential American magazines, from GQ to The New Yorker — and hundreds of Web and television images — depict this new era of American infatuation as a dance, accompanied by, what else, rum, cars, cigars, and mulattas. No doubt the party is back on.

The motivation now is less to restore the border with Cuba than to recover lost time and re-conquer the last nearby market not deeply penetrated by American capital. In this new climate, everything Cuban is hot. To learn how the Cuba Libre (and not the Piña Colada) came about is sexy. To invest in run-down urban areas (in Havana, not in San Juan) is sexy. It is also sexy to invite university students to study the biosphere. “Cuba is inaccessible,” the professor observes. “It makes the trip sound much sexier, don’t you think?”

Even Cuban poverty is sexy — at least on the front page of the New York Times. This past March 20th, 2016, the paper made the unusual choice of running stories about both islands. As scholar Rima Brusi quickly noted, the Cuban article was not only above the fold — it similarly included striking photographs of Havana’s ruins resembling realist paintings. Furthermore, while Cuba’s poverty may cause “aching despair,” the Times re-assures its readers that Cubans “brim with so much life. They wait, coiled with anticipation” (yet again). In contrast, Puerto Rico’s poverty and landscape are, in addition to ugly, repellent, and dangerous: the island is a “warm, wet paradise veined with gritty poverty, the ideal environment for the [Zika] mosquitoes carrying the virus.”

Many see little wrong with these depictions for at least two reasons. While the revolution was, in part, a response to U.S. domination, the formal rupture between governments and the fact that Fidel Castro took over allow the Americans to return as if they had nothing to do with Cuba’s fortunes. With Puerto Rico, denial is impossible, particularly now, when, to a large extent due to American failed policies, the country is emptying out by the thousands and the economy is near collapse.

After 118 years, it is clear that the self-designated greatest democracy in the world failed to provide what it promised upon arrival — prosperity and freedom — making Puerto Rico an uncomfortable matter for Americans. If Cuba is a colorful fantasy that lasts and lasts like a Life Savers lollipop, Puerto Rico is a nuisance, like a wad of gum stuck to the bottom of a shoe. It is also a damning mirror reflecting back an image of the U.S. as just another country imposing its power — not for the good of humanity, but to advance its own interests.

Ultimately, the irony is that being considered sexy or not, and following different paths of reform and revolution under its good neighbor, Cuba and Puerto Rico have ended up in a similar place: ruined. Though, once more, the U.S. mostly has eyes for one. The danger for Cuba is that, to quote philosopher Gilles Deleuze: “If you’re trapped in the dream of another, you’re screwed.” In other words, as Puerto Ricans know, possession without passion adds salt to the wound. But there are amores que matan — loves that kill — and looks too.

Why Do Americans Find Cuba Sexy — but Not Puerto Rico?

yesterday9 min read

Why Do Americans Find Cuba Sexy — but Not Puerto Rico?

The history of why the American imagination treats two Caribbean islands very differently.

By Frances Negrón-Muntaner

Cartoon in the Boston Globe, May 1898. (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

The editor of a leading publishing house was not moved by my impassioned pitch: to write a major English-language biography of Julia de Burgos, a Puerto Rican poet and national icon whose name or likeness can be found in dozens of murals, buildings, and street signs across Latino neighborhoods. To my proposal, he simply said: “Nah. It wouldn’t sell. The only Latin biography I’d publish is José Martí.”

“José Martí?” I repeated, incredulous. Certainly, the renowned Cuban poet and pro-independence hero merits not one but many biographies. The categorical tone of his reply, however, puzzled me: “Why only Martí?” The editor smiled: “Martí comes from a sexy country.” “But he’s not sexy,” I countered.

The double standard made little sense. Yet, it could be explained — and should. For how Americans view Cuba and Puerto Rico has both history and consequences, including now when the U.S. government just imposed a fiscal control board on Puerto Rico and Cuba warily embraces American investment.

Since the islands first entered the young republic’s field of vision in the 19th century, Cuba has always been the more attractive of the two. It was bigger. It was more elegant. But, above all, it was closer. In the American imagination, Cuba appeared as emotional boundary and vulnerable national border, an Achilles’ heel whose possession by another could bring about the destruction of the United States itself. In fact, the American fear that a different country than Spain would govern Cuba reached such heights that, between 1823 and 1897, the U.S. made no fewer than four attempts to purchase the island. To be in control of Cuba’s destiny grew into an obsession.

If Cuba is a colorful fantasy that lasts and lasts like a Life Savers lollipop, Puerto Rico is a nuisance, like a wad of gum stuck to the bottom of a shoe.

When the U.S. finally took up arms in the matter during the Spanish-American War of 1898, its fixation with Cuba intensified. Invoking libidinous and political fantasies, the press represented the island in numerous caricatures and narratives as a beautiful young woman or a starving mother, crying out for a savior who could rescue her from Spain. That Cuban pro-independence fighters were largely missing from the picture leaves little doubt that Uncle Sam was interested solely in saving Cuba — not Cubans.

Up until the U.S. readied to invade Puerto Rico, the island was hardly mentioned in the nation’s war coverage. Yet as the military campaign there advanced, references to Puerto Rico in the American press increased. Unlike with Cuba, however, the taking of “Porto Rico” is often described in cold imperial terms: Politicians and experts agreed on the island’s strategic advantages and business potential; they also assured readers that Puerto Rico was too small to be independent and would benefit from American guidance. Journalists likewise reported, in short articles underlining the island’s lack of importance, that it was Puerto Ricans and not Americans who were “excited” about the invasion.

Once in control of the islands after the 1898 Treaty of Paris, the U.S. imposed military governments in Cuba and Puerto Rico. In print, the Cuban belle morphed into a black boy who, similar to his Puerto Rican cousin, needed Uncle Sam to forever teach him the art of self-government. Nevertheless, whereas Americans saw themselves as superior to both Cubans and Puerto Ricans, the ethos of independence made them feel closer to Cubans. In the words of influential congressman Henry Teller, author of the amendment precluding the U.S. annexation of Cuba: “I don’t like the Puerto Rican. They are not fighters like the Cubans. They were under Spanish tyranny for centuries without showing enough manhood to oppose it. Such a race is unworthy of U.S. citizenship.”

The next step was as creative as it was crafty. While the desire to annex Cuba culminated in the American “concession” of independence in 1902, the U.S. viewed it as theirs. Puerto Rico, however, is legally possessed outright, even as the Supreme Court decided the island, like a superfluous accessory, belongs to — but is not part of — the U.S. Although the U.S. eventually extended citizenship to Puerto Rico’s residents in 1917, this formality had little to do with integration or civil rights. As colonial governor Arthur D. Yager put it, the U.S. citizenship of Puerto Ricans simply indicated that, “we have determined … the American flag will never be lowered in Puerto Rico.” Consequently, islanders entered the equivalent of political limbo: they could serve in the U.S. military but not vote for the president nor have a voting congressional representation.

By the 1920s, America’s attraction to Cuba eagerly returned to its primal idiom: sex. From the Roaring Twenties to the “lost decade” of the 1950s, Americans made Havana their go-to destination for the three Ds: dancing, drinking, and dealing. Puerto Rico, despite having spectacular beaches and a climate similar to the island next door, could boast only one luxury hotel, the Condado Vanderbilt, until 1949, when the Caribe Hilton was built — at the behest of the insular government. If Cuba was triple-D, Puerto Rico was triple-P: poor, puny, and passive. Americans remained hooked on Havana.

At least, until el mambo came to an end. Though the U.S.-Cuba affair was invariably tense, the Cuban Revolution of 1959 abruptly ended America’s romance, yet turned the island into a much more alluring girl. Again, Cuba became the forbidden fruit that must be re-acquired at all costs through invasions, embargoes, and assassination attempts — and no wonder: By 1958, Cuba was not just a popular adult amusement park for Americans. U.S. capital controlled a large portion of the island’s economy, including 90 percent of the electric and telephone industries, 83 percent of the railway commerce, and 43 percent of the sugar business.

Simultaneously, if the masculinity of young Cuban men-at-arms was a turnoff for the American political elite, it attracted leftist and minority intellectuals, who understood the revolution as a direct challenge to the racist and colonial policies of the U.S. at home and abroad. Even further, the revolution raised Cubans to the level of international sex symbols, models of how a small and poor nation could confront the most powerful military in the world and win. This development immediately affected Puerto Rico.

To counter the rise of Cuba rebelde as a sexy global brand, the U.S re-fashioned Puerto Rico as a plain but attractive alternative by offering corporate incentives and tax breaks. The new look is evident in a 1958 cover of Time magazine, featuring the island’s gray-haired governor Luis Muñoz Marín. Once more, Puerto Rico is sold in clinical terms, this time, as a laboratory “about democracy in Latin America.” According to the magazine, Puerto Rico demonstrates how good capitalism can be when Latin America embraces U.S. investment and rejects nationalism. Clinical or otherwise, the experiment soon lost funding and went into crisis. Not only did the ensuing Puerto Rican “economic miracle” last less than two decades, it required the exportation of over 700,000 Caribbean souls to cities such as New York to serve as cheap and expendable labor.

The motivation now is less to restore the border with Cuba than to recover lost time and re-conquer the last nearby market not deeply penetrated by American capital.

Ironically, even though many New Yorkers regarded Puerto Rican migrants as “tropical scum,” their origin “somewhere down there,” made it possible for a handful to be assimilated through the Latin Lover and sexy spitfire stereotypes. After 1959, the situation for Cubans fleeing to the U.S. is reversed: Although they received a warmer welcome, for Americans, the heat stayed behind. Whether considered model minorities as the first wave of exiles or riffraff after the 1980 Mariel boatlift, Cubans in America rarely earn the “most sexy” title–with the exception of those who work really hard at it like Pitbull. As always, the crown of sexy is reserved collectively for those who remain or live in Cuba — and Che, of course.

It is, then, not surprising that, in the last two years, as relations between the U.S. and Cuba have “thawed” and President Barack Obama became the first American president to visit since 1928, sexual rhetoric has returned as a vital component of the rapprochement, foreshadowing conflicts to come. In the first few months of 2015 alone, dozens of influential American magazines, from GQ to The New Yorker — and hundreds of Web and television images — depict this new era of American infatuation as a dance, accompanied by, what else, rum, cars, cigars, and mulattas. No doubt the party is back on.

The motivation now is less to restore the border with Cuba than to recover lost time and re-conquer the last nearby market not deeply penetrated by American capital. In this new climate, everything Cuban is hot. To learn how the Cuba Libre (and not the Piña Colada) came about is sexy. To invest in run-down urban areas (in Havana, not in San Juan) is sexy. It is also sexy to invite university students to study the biosphere. “Cuba is inaccessible,” the professor observes. “It makes the trip sound much sexier, don’t you think?”

Even Cuban poverty is sexy — at least on the front page of the New York Times. This past March 20th, 2016, the paper made the unusual choice of running stories about both islands. As scholar Rima Brusi quickly noted, the Cuban article was not only above the fold — it similarly included striking photographs of Havana’s ruins resembling realist paintings. Furthermore, while Cuba’s poverty may cause “aching despair,” the Times re-assures its readers that Cubans “brim with so much life. They wait, coiled with anticipation” (yet again). In contrast, Puerto Rico’s poverty and landscape are, in addition to ugly, repellent, and dangerous: the island is a “warm, wet paradise veined with gritty poverty, the ideal environment for the [Zika] mosquitoes carrying the virus.”

Many see little wrong with these depictions for at least two reasons. While the revolution was, in part, a response to U.S. domination, the formal rupture between governments and the fact that Fidel Castro took over allow the Americans to return as if they had nothing to do with Cuba’s fortunes. With Puerto Rico, denial is impossible, particularly now, when, to a large extent due to American failed policies, the country is emptying out by the thousands and the economy is near collapse.

After 118 years, it is clear that the self-designated greatest democracy in the world failed to provide what it promised upon arrival — prosperity and freedom — making Puerto Rico an uncomfortable matter for Americans. If Cuba is a colorful fantasy that lasts and lasts like a Life Savers lollipop, Puerto Rico is a nuisance, like a wad of gum stuck to the bottom of a shoe. It is also a damning mirror reflecting back an image of the U.S. as just another country imposing its power — not for the good of humanity, but to advance its own interests.

Ultimately, the irony is that being considered sexy or not, and following different paths of reform and revolution under its good neighbor, Cuba and Puerto Rico have ended up in a similar place: ruined. Though, once more, the U.S. mostly has eyes for one. The danger for Cuba is that, to quote philosopher Gilles Deleuze: “If you’re trapped in the dream of another, you’re screwed.” In other words, as Puerto Ricans know, possession without passion adds salt to the wound. But there are amores que matan — loves that kill — and looks too.

Why Do Americans Find Cuba Sexy — but Not Puerto Rico?

I don't know any Venezuelans in Brazil tho. But I don't know anyone in the north, it's like someone from Miami knowing about north dakota's Canadian border. I'm ignorant as fukk sadly

I don't know any Venezuelans in Brazil tho. But I don't know anyone in the north, it's like someone from Miami knowing about north dakota's Canadian border. I'm ignorant as fukk sadly