You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Essential Afro-Latino/ Caribbean Current Events

- Thread starter Poitier

- Start date

More options

Who Replied?“Champeta is liberation”: The indestructible sound system culture of Afro-Colombia

BY APRIL CLARE WELSH, AUG 21 2016

For decades confined to Colombia’s poor coastal regions and condemned by conservative politicians as violent and corrupting, the African-Latin fusion sound of champeta is finally cracking into the mainstream. April Clare Welsh speaks to Palenque Records founder Lucas Silva to discover the “visionary black music” of a marginalised population. Scroll to the end for a huge champeta playlist.

Sound systems are the radio stations of champeta. Forty years ago, brightly painted “picós”, as they are called in Spanish, could be found in every neighbourhood around Cartagena, the Colombian port city that birthed the percussion-heavy mix of African and Colombian musical styles known as champeta. These Jamaican-inspired handmade structures arrived in Colombia in the 1950s and became a fixture at fiestas, carnivals and family parties along the country’s Caribbean coast, home to much of the country’s Afro-Colombian population. For the next two decades, the selectors – known as picóteras – would spin music from a traditional Latin songbook of salsa, vallenato, guaracha, bolero, tango and rancheras on famous sound systems like La Salsa de Puerto Rico, El Rojo, El Dragon, El Conde, and what is still largely considered to be the most popular picó in Cartagena, El Rey de Rocha.

Picós served a social and communal function for people living in the poorer areas, or barrios, of Cartagena and the region’s largest port, Barranquilla, offering a cheap form of entertainment as well as contributing to the area’s informal economy. When “música Africana” swept the region during the ‘70s and ‘80s, the sound systems played a vital role in building a collective diasporan identity for many Afro-Colombians living in a country heavily scored along race and class lines. Colombia’s black voices have been silenced and suppressed since European colonisers started bringing enslaved Africans to South America in the 16th century, and the country’s black population has largely been confined to the poorer coastal areas since slavery’s abolition. According to the most recent national census, while just over 10% of the country’s population is of African ancestry, the northern section of Colombia’s Pacific coast is over 80% black.

El Rojo sound system | Photo via: Fabian Altahona

The African music phenomenon – which also embraced Caribbean styles like zouk from Martinique and Guadeloupe, soca from Trinidad and reggae and dancehall from Jamaica – soon guaranteed picó owners a steady supply of records from all over Africa. There are different theories as to how these records ended up in Colombia, but most believe that they arrived with West African sailors docking in Cartagena and Barranquilla in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s. The sailors came with soukous from the Congo basin, Nigerian highlife and South African mbaqanga, and records by artists like Nigeria’s Fela Kuti and Prince Nico Mbarga, Cameroon’s Louisiana Tilda and Ivory Coast’s Ernesto Djédjé. The music was an instant hit with Colombia’s coastal population, or costeños, and was readily absorbed into the region’s picó culture.

Lucas Silva, the Bogota-born owner of champeta-focused label Palenque Records, says Colombians loved the African songs they were hearing so much that they began bootlegging them. “But after physically copying the records as much as they could, a number of Latin musicians decided to make their own versions,” he tells me when me meet in Bogota, the sprawling capital city. “That’s how the champeta blueprint came into being.” Picó owners would rip off record covers and throw away the sleeves to ensure exclusivity and keep their competitors at bay while also renaming the record in Spanish; Fela Kuti´s 1972 track ʻShakaraʼ became ʻShakalao’, for example.

Local record labels soon jumped on the bandwagon and began releasing records by Afro-Colombian artists like Wganda Kenya, who were signed to the prolific recording outpost Disco Fuentes (and who last year released a 12” on JD Twitch’s Autonomous Africa imprint), while other labels like Discos Tropical and Orbe & Costeno also embraced this new phenomenon. (More recently, in 2012 the African and Latin American reissue label Analog Africa documented the movement’s multitudinous sounds in its essential compilation The Colombian Melting Pot: Diablos del Ritmo, which spans everything from Afrobeat to Caribbean funk during the period from 1960 to 1985.)

“You can identify champeta by the pulsating beat and the rhythm of the African guitars which give it its identity,” explains Silva. Champeta has a signature three-part structure: an introduction, a chorus and a frantic, repetitive section called “el Despeluque” (which translates roughly as “messed up hair”, or perhaps more broadly, “lose your shyt”). Songs are predominantly sung in Spanish, or the Spanish-based creole language Palenquero, which is native to San Basillio de Palenque, recognised as the first African free town in South America. Lyrics can be emotionally, socially or religiously charged, mostly touching on everyday life.

“Champeta is the most explosive rhythm coming out of the Caribbean’s belly since the end of the century,” writes Silva on his label’s Bandcamp page, “and it’s rewriting the ‘New Testament of Afro-American music’.” It’s exactly these explosive rhythms that I heard blasted from car radios, bars and patios in Cartagena and Santa Marta, Colombia’s oldest surviving city. After spending a week in Bogota, I got a dose of Caribbean sunshine over a few days in Cartagena, where I ended up buying a handful of champeta CD-Rs from a market vendor.

“This is the music to dance to,” he excitedly told me, and he wasn’t wrong; two nights later I found myself flailing around to champeta at a small shop-cum-bar near my hotel. Many of the drinking dens in Colombia double up as convenience stores, stocking food like empanadas and various household items. I had just popped in to buy a packet of cigarettes when a Colombian man started talking to me from his table near the counter. A champeta song was playing loudly on the radio as I sat down to join him and his friends for a beer, and after conversing in broken Spanglish for an hour while guzzling down cold bottles of Club Colombia, we got up on our feet for a dance. As my new friend Sebastian told me: “This is the music of the coast. This is ours, this is what we have.”

BY APRIL CLARE WELSH, AUG 21 2016

For decades confined to Colombia’s poor coastal regions and condemned by conservative politicians as violent and corrupting, the African-Latin fusion sound of champeta is finally cracking into the mainstream. April Clare Welsh speaks to Palenque Records founder Lucas Silva to discover the “visionary black music” of a marginalised population. Scroll to the end for a huge champeta playlist.

Sound systems are the radio stations of champeta. Forty years ago, brightly painted “picós”, as they are called in Spanish, could be found in every neighbourhood around Cartagena, the Colombian port city that birthed the percussion-heavy mix of African and Colombian musical styles known as champeta. These Jamaican-inspired handmade structures arrived in Colombia in the 1950s and became a fixture at fiestas, carnivals and family parties along the country’s Caribbean coast, home to much of the country’s Afro-Colombian population. For the next two decades, the selectors – known as picóteras – would spin music from a traditional Latin songbook of salsa, vallenato, guaracha, bolero, tango and rancheras on famous sound systems like La Salsa de Puerto Rico, El Rojo, El Dragon, El Conde, and what is still largely considered to be the most popular picó in Cartagena, El Rey de Rocha.

Picós served a social and communal function for people living in the poorer areas, or barrios, of Cartagena and the region’s largest port, Barranquilla, offering a cheap form of entertainment as well as contributing to the area’s informal economy. When “música Africana” swept the region during the ‘70s and ‘80s, the sound systems played a vital role in building a collective diasporan identity for many Afro-Colombians living in a country heavily scored along race and class lines. Colombia’s black voices have been silenced and suppressed since European colonisers started bringing enslaved Africans to South America in the 16th century, and the country’s black population has largely been confined to the poorer coastal areas since slavery’s abolition. According to the most recent national census, while just over 10% of the country’s population is of African ancestry, the northern section of Colombia’s Pacific coast is over 80% black.

El Rojo sound system | Photo via: Fabian Altahona

The African music phenomenon – which also embraced Caribbean styles like zouk from Martinique and Guadeloupe, soca from Trinidad and reggae and dancehall from Jamaica – soon guaranteed picó owners a steady supply of records from all over Africa. There are different theories as to how these records ended up in Colombia, but most believe that they arrived with West African sailors docking in Cartagena and Barranquilla in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s. The sailors came with soukous from the Congo basin, Nigerian highlife and South African mbaqanga, and records by artists like Nigeria’s Fela Kuti and Prince Nico Mbarga, Cameroon’s Louisiana Tilda and Ivory Coast’s Ernesto Djédjé. The music was an instant hit with Colombia’s coastal population, or costeños, and was readily absorbed into the region’s picó culture.

Lucas Silva, the Bogota-born owner of champeta-focused label Palenque Records, says Colombians loved the African songs they were hearing so much that they began bootlegging them. “But after physically copying the records as much as they could, a number of Latin musicians decided to make their own versions,” he tells me when me meet in Bogota, the sprawling capital city. “That’s how the champeta blueprint came into being.” Picó owners would rip off record covers and throw away the sleeves to ensure exclusivity and keep their competitors at bay while also renaming the record in Spanish; Fela Kuti´s 1972 track ʻShakaraʼ became ʻShakalao’, for example.

Local record labels soon jumped on the bandwagon and began releasing records by Afro-Colombian artists like Wganda Kenya, who were signed to the prolific recording outpost Disco Fuentes (and who last year released a 12” on JD Twitch’s Autonomous Africa imprint), while other labels like Discos Tropical and Orbe & Costeno also embraced this new phenomenon. (More recently, in 2012 the African and Latin American reissue label Analog Africa documented the movement’s multitudinous sounds in its essential compilation The Colombian Melting Pot: Diablos del Ritmo, which spans everything from Afrobeat to Caribbean funk during the period from 1960 to 1985.)

“You can identify champeta by the pulsating beat and the rhythm of the African guitars which give it its identity,” explains Silva. Champeta has a signature three-part structure: an introduction, a chorus and a frantic, repetitive section called “el Despeluque” (which translates roughly as “messed up hair”, or perhaps more broadly, “lose your shyt”). Songs are predominantly sung in Spanish, or the Spanish-based creole language Palenquero, which is native to San Basillio de Palenque, recognised as the first African free town in South America. Lyrics can be emotionally, socially or religiously charged, mostly touching on everyday life.

“Champeta is the most explosive rhythm coming out of the Caribbean’s belly since the end of the century,” writes Silva on his label’s Bandcamp page, “and it’s rewriting the ‘New Testament of Afro-American music’.” It’s exactly these explosive rhythms that I heard blasted from car radios, bars and patios in Cartagena and Santa Marta, Colombia’s oldest surviving city. After spending a week in Bogota, I got a dose of Caribbean sunshine over a few days in Cartagena, where I ended up buying a handful of champeta CD-Rs from a market vendor.

“This is the music to dance to,” he excitedly told me, and he wasn’t wrong; two nights later I found myself flailing around to champeta at a small shop-cum-bar near my hotel. Many of the drinking dens in Colombia double up as convenience stores, stocking food like empanadas and various household items. I had just popped in to buy a packet of cigarettes when a Colombian man started talking to me from his table near the counter. A champeta song was playing loudly on the radio as I sat down to join him and his friends for a beer, and after conversing in broken Spanglish for an hour while guzzling down cold bottles of Club Colombia, we got up on our feet for a dance. As my new friend Sebastian told me: “This is the music of the coast. This is ours, this is what we have.”

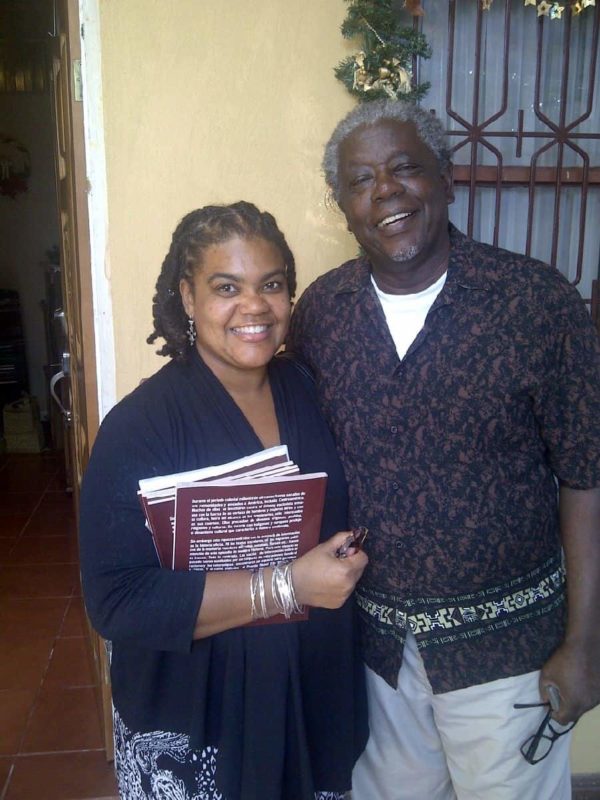

Ané Swing, aka Viviano Torres, and Son Palenque’s Justo Valdez in Cartagena, 2015. Photo by Lucas Silva

“Champeta was a movement that was both punk and African at its core – musical and cultural liberation for the black population,” Silva later tells me. Differing forms of the champeta dance, which were born from salsa rhythms, Puerto Rican jíbaro and reggae, began as a kind of therapy, although have since progressed into faster, raunchier versions. “This was dancing to unite the collective soul of Colombia’s mixed Indian, Latin and African heritage.”

There are several theories about the origin of the word champeta, but it likely stems from the champeta knife used by workers in Cartagena’s Bazurto market. In the ‘70s, these workers would meet regularly to listen to African music on picós, but over the decades the word has been deliberately sullied by conservatives seeking to attach connotations of violence to the music. This kind of prejudice against the country’s black population has stifled the genre’s growth over the years, with Colombian politicians even attempting to enforce a national ban on champeta, accusing the music of encouraging violence and teenage pregnancy.

“Champeta is a not a violent rhythm or one that is sexually charged,” says Pocho, a member of a traditional champeta group called Tribu Baru, over the phone from his hometown of Barranquilla. “I grew up listening to it and it doesn’t have any negative connotations for me. Yes, champeta is a knife, so people translate a champetura as ‘the one with a knife’ – but it’s all complete sensationalism, of course!”

Although Pocho lives in Barranquilla, the six members of his band met in Bogota six years ago. “At sound system parties you would hear songs from all over the world, but you would mostly hear soukous music,” he says. “About 80% of the music we make is influenced by the soukous that we all grew up listening to, along with Caribbean music from Haiti and reggae from Jamaica – sound systems brought a lot of music to us and we want to show that in our music. We use the aesthetic of the sound systems because to be a champetura, that’s the culture surrounding it all.”

Throughout the ‘70s and ‘80s, a steady stream of homegrown champeta stars – including one of the genre’s best-loved artists, Abelardo Carbonó – lit up the coast’s music scene, while the band Son Palenque, who married local palenquera culture to modern guitar and saxophone sounds, were the leading lights of the champeta criolla movement in the ‘80s (criolla is the Spanish word for ‘creole’), along with Estrellas De Caribe, who seared their sound with a psychedelic edge. Featuring songs sung in the Palenquero language, champeta criolla was largely confined to San Basilio de Palenque, and the town is seen by many as the source of champeta owing to its history as a free town. In the middle of the 17th century, runaway African slaves began settling in their own towns to escape from their oppressors and the risk of being burned to death by the Spanish Inquisition. These settlements became known as palenques, and San Basilio de Palenque was the first of its kind – in 2005, the village was given special heritage status by UNESCO.

Diogenes Salgado, vocalist with Estrellas De Caribe, who died in 2015. Photo by: Lucas Silva

Silva, the founder of Palenque Records and self-styled ‘DJ Champeta-Man’, began researching Afro-Colombian music in the early ‘90s when he was living in France. He flew back to his country in 1994 when he heard about the music that had been gripping the coast, and when he travelled to Palenque he discovered a whole community of artists reinterpreting folk traditions in exciting new ways. In 1998, Silva released the compilation album Champeta Criolla – New African Music From Colombia Vol. 1, bringing the music to a market outside of Colombia, and the record’s popularity helped sow the seeds of Silva’s international reputation. Over the past two decades, Silva has released over 20 champeta records, both on his own label and in collaboration with others, like the Palenque! Palenque!compilation for Soundway in 2010.

Last January, Palenque released a second volume ofChampeta Criola subtitled “Visionary Black Music From Colombia”. Spanning music made between 1984 and 1999, the 25 tracks were produced and recorded by what he dubs “the architects of the Champeturo sound of Cartagena,” including Chawala, selector for the Rey De Rocha Sound System, producer Yamiro Marin, studio engineers Luis Garcia and Alvaro Cuellar, and a plethora of singers. The album is a vivid patchwork of African and Latin styles, from Medellin-based Louis Towers’ ‘Mama Africa’, which fuses scratching and nostalgic blasts of accordion with urgent drums, to Latin hip-swing and horns from Batata y Su Rhumba’s ‘Ataole’ and deejay toasting courtesy of Elio Boom’s ‘El Fulo.’ There are also calypso-infused tracks, and the warm call-and-response vocals of Son San’s ‘Mangaina Vae ya’. The album unbottles what Silva refers to as champeta’s “wild cultural mix,” but as he explains, he had to work hard to spread the gospel of champeta outside its coastal home.

“It was a very tough fight. There is a lot of racism in this county and champeta was too new – people didn’t understand it, it was a shock, like with any revolution. I remember coming back to Bogota in the mid ‘90s and everybody hated champeta. They all said it was ‘stupid’ music and too sexual. But the lyrics were just covering normal things about life. Bogota was a very white city in the ‘90s – everyone was listening to rock music at the time. Rock music was for rich people and cumbia and champeta were for the poor people.”

Cassettes from El Rojo “La Cobra de Barranquilla” sound system | Photo via: Fabian Altahona

While Colombian society is by no means a liberal, tolerant utopia, things have started to move forward in recent years, and champeta has begun to be adapted into more commercial, digital strains. Urban champeta is the most-up-to-date electronic refit of the genre, melding dancehall and reggaetón with radio-friendly pop music. Trailblazer Kevin Florez, who began life as a rapper, is its most successful star, having made it onto national radio playlists – a success usually reserved for salsa and reggaeton artists, or those willing to pay the required commercial fees. A Florez song popped up on a restaurant’s playlist when I was eating in Bogota one night; he has made it out of the coast and into the country’s wider musical consciousness.

“Champeta is still a fairly new trend in Bogota,” adds Silva, who this year is celebrating the label’s 20th anniversary with a record of electronic remixes of champeta. “But it’s getting there, and people are starting to support it more at venues, bars and clubs. Along with the social climate, the internet has changed the way the music is consumed, distributed and produced. Everything is different now. New artists are all over the internet and it has broken down the barriers. When I started putting out champeta records, it was at the time confined to the ghetto. Now you have a singer who has a Facebook page with a lot of fans. It’s basically party music, and therefore there has been a proliferation of commercial artists who make a lot of money.”

So champeta is finally becoming commercial. “But it’s like any kind of music,” he warns. “You have good champeta, bad champeta, stupid champeta. It’s for all kinds of tastes. The black artists who are from the ghetto, they want to make money, they want to be famous. They want to go to America, to tour Europe – and what’s so wrong with that? Some of their music I like, some of it I don’t like, but there is more than enough room for all of it.”

April Clare Welsh is on Twitter

Dip into our huge playlist of champeta tracks old and new.

“Champeta is liberation”: The indestructible sound system culture of Afro-Colombia

subs

Jim Jones Is Unaware Of How The Diaspora Works…

Marjua Estevez @_MsEstevez | August 26, 2016 - 10:36 am

CREDIT: Getty Images

Earlier this year, during an interview with Power 105.1 The Breakfast Club, Dascha Polanco and the show’s hosts discussed the controversial casting of Zoe Saldana in the Nina Simone biopic. Talks concerning Afro-Latinidad ensued, and Charlamagne Tha God became very confused about how someone could simultaneously be black and Latina. Soon thereafter, on the Brilliant Idiots podcast, a conversation—if you can call it that—about blackness outside of America (namely the Caribbean), aimed at further breaking down the concept, took place.

READ: Dascha Polanco: “If I’m Not American Or Latina Enough, Then What Am I?”

On Thursday (Aug. 25), Jim Jones and his partner of 11 years Chrissy Lampkin in a recent interview with Hip-Hop Wired was asked about Lampkin’s Afro-Cuban ancestry, to which the Harlem rapper quipped, “She’s Mexican.”

After a fleeting moment of awkward silence and chuckles were exchanged, Jim Jones, who is also Afro-Latino, of Aruban and Puerto Rican descent, added: “Where does Afro-Cuban come from. I never heard of Afro-Cuban. I heard of Afro-American. So does that mean there’s Afro-Asian?”

Lampkin finally interjected with “I am black and Cuban,” adding, “my Cuban side of the family makes fun of me because I don’t speak Spanish,” something that is often a source of insecurity or even shame for many U.S. Latinxs.

READ: Tongue Tactics: 9 Afro-Latino Poets Who Get Radical On The Mic

But guess what, Chrissy girl, you still #BrownGirlFly and #BlackGirlMagic and Afro-Cuban as all hell, because speaking Spanish doesn’t make you anymore Latino than speaking English makes you American, and blackness outside of the U.S. is—surprise—real. When the Transatlantic Slave Trade happened, most of the slaves were brought to the Caribbean, and of that region in the 19th century, Cuba itself absorbed a majority of the Africans forced to migrate.

Being Latino is an ethnicity in which any number of races can exist. And yes, Jimmy, there is such a thing as Afro-Asian.

Jim Jones Is Unaware Of How The Diaspora Works…

Marjua Estevez @_MsEstevez | August 26, 2016 - 10:36 am

CREDIT: Getty Images

Earlier this year, during an interview with Power 105.1 The Breakfast Club, Dascha Polanco and the show’s hosts discussed the controversial casting of Zoe Saldana in the Nina Simone biopic. Talks concerning Afro-Latinidad ensued, and Charlamagne Tha God became very confused about how someone could simultaneously be black and Latina. Soon thereafter, on the Brilliant Idiots podcast, a conversation—if you can call it that—about blackness outside of America (namely the Caribbean), aimed at further breaking down the concept, took place.

READ: Dascha Polanco: “If I’m Not American Or Latina Enough, Then What Am I?”

On Thursday (Aug. 25), Jim Jones and his partner of 11 years Chrissy Lampkin in a recent interview with Hip-Hop Wired was asked about Lampkin’s Afro-Cuban ancestry, to which the Harlem rapper quipped, “She’s Mexican.”

After a fleeting moment of awkward silence and chuckles were exchanged, Jim Jones, who is also Afro-Latino, of Aruban and Puerto Rican descent, added: “Where does Afro-Cuban come from. I never heard of Afro-Cuban. I heard of Afro-American. So does that mean there’s Afro-Asian?”

Lampkin finally interjected with “I am black and Cuban,” adding, “my Cuban side of the family makes fun of me because I don’t speak Spanish,” something that is often a source of insecurity or even shame for many U.S. Latinxs.

READ: Tongue Tactics: 9 Afro-Latino Poets Who Get Radical On The Mic

But guess what, Chrissy girl, you still #BrownGirlFly and #BlackGirlMagic and Afro-Cuban as all hell, because speaking Spanish doesn’t make you anymore Latino than speaking English makes you American, and blackness outside of the U.S. is—surprise—real. When the Transatlantic Slave Trade happened, most of the slaves were brought to the Caribbean, and of that region in the 19th century, Cuba itself absorbed a majority of the Africans forced to migrate.

Being Latino is an ethnicity in which any number of races can exist. And yes, Jimmy, there is such a thing as Afro-Asian.

Jim Jones Is Unaware Of How The Diaspora Works…

Jim Jones & Chrissy Try To Figure Out What

Chick herself didn't even know what it means either. :jimohreally: I guess she's half AA and half Cuban but the Cuban side ain't Black.

Haiti's peanut producers oppose 500-tonne US donation

Peanut producers in Haiti have united to block the delivery of a 500-tonne shipment of nuts from the US.

They say the shipment threatens to undermine the livelihood of thousands of people in the country.

According to the World Bank, extreme poverty in the country has fallen from 31 to 24 percent over the last decade but remains the poorest country in the Americas and one of the poorest in the world (with a GDP per capita of $846 in 2014).

The US Department of Agriculture argues the shipment is a donation to alleviate hunger among Haitian schoolchildren but the locals are strongly opposing the move.

"Our peanuts are natural, we can use them over and over again," farmers' leader Josapha Antonice Guillaume told Al Jazeera.

"We don't modify our crops. We will not accept anyone or any institution that tries to destroy them. We will fight. Peanuts are part of our heritage."

More than 50 groups of farmers and aid workers, both Haitian and foreign, have issued a joint statement calling on the US to stop the shipment.

"The dumping of these peanuts will create a big catastrophe, even bigger than the destruction of our rice production," said Jean Pierre Ricot, an agriculture expert.

"Hundreds of thousands of families lost their livelihoods because of those policies. To face the problem, we need a fundamental battle to stop these policies."

Some international aid experts warn that the US peanut donation could eventually become another cautionary tale about humanitarian aid from a wealthy nation that undermines a flimsy economy in a poor one.

Source: Al Jazeera News and agencies

Haiti Latin America Poverty Poverty & Development

Peanut producers in Haiti have united to block the delivery of a 500-tonne shipment of nuts from the US.

They say the shipment threatens to undermine the livelihood of thousands of people in the country.

According to the World Bank, extreme poverty in the country has fallen from 31 to 24 percent over the last decade but remains the poorest country in the Americas and one of the poorest in the world (with a GDP per capita of $846 in 2014).

The US Department of Agriculture argues the shipment is a donation to alleviate hunger among Haitian schoolchildren but the locals are strongly opposing the move.

"Our peanuts are natural, we can use them over and over again," farmers' leader Josapha Antonice Guillaume told Al Jazeera.

"We don't modify our crops. We will not accept anyone or any institution that tries to destroy them. We will fight. Peanuts are part of our heritage."

More than 50 groups of farmers and aid workers, both Haitian and foreign, have issued a joint statement calling on the US to stop the shipment.

"The dumping of these peanuts will create a big catastrophe, even bigger than the destruction of our rice production," said Jean Pierre Ricot, an agriculture expert.

"Hundreds of thousands of families lost their livelihoods because of those policies. To face the problem, we need a fundamental battle to stop these policies."

Some international aid experts warn that the US peanut donation could eventually become another cautionary tale about humanitarian aid from a wealthy nation that undermines a flimsy economy in a poor one.

Source: Al Jazeera News and agencies

Haiti Latin America Poverty Poverty & Development

Multi-million-$ tourism loan facility launched in Jamaica

29 Augsut 2016

KINGSTON, Jamaica--Minister of Tourism Edmund Bartlett has launched a special J $20 million (US $157,735) revolving loan facility to boost the compliance of small tourism properties, attractions and businesses on Jamaica’s eco-friendly south coast.

The initiative for community tourism enterprises in Treasure Beach, St. Elizabeth, forms part of the Ministry of Tourism’s National Community Tourism Policy and Strategy aimed at developing community tourism island-wide to diversify the island’s tourism product.

Minister Bartlett said it would serve as a pilot project for community tourism, adding that he hoped it could be replicated across the island.

The facility financed by the Tourism Enhancement Fund (TEF), serves as counterpart funding for the Compete Caribbean Initiative which has committed some US $627,000 to date, to develop community tourism in the area.

The loan scheme is being administered by Jamaica National Small Business Loans (JNSBL). Applicants will be able to access loans of up to J $2 million (US $15,773) at a highly subsidised interest rate of 3 per cent per annum for five years. Several small business operators present at the launch last week signed loan applications on the spot.

Minister Bartlett said the scheme would enable the enterprises in Treasure Beach to become compliant and more appealing, which he said is crucial to positioning the area as a unique destination offering a “rustic luxury experience which the rich and famous seek when they want to escape from the formal luxurious settings that are characteristic of some of the destinations that we know, where the link with nature is never broken but the quality of the creature comforts are still at the highest level.”

In anticipation of increased tourist traffic, roads in Treasure Beach are to be improved and consideration given to offering air travel to the south coast by upgrading the Lionel Densham Aerodrome. ~ Caribbean360 ~

29 Augsut 2016

KINGSTON, Jamaica--Minister of Tourism Edmund Bartlett has launched a special J $20 million (US $157,735) revolving loan facility to boost the compliance of small tourism properties, attractions and businesses on Jamaica’s eco-friendly south coast.

The initiative for community tourism enterprises in Treasure Beach, St. Elizabeth, forms part of the Ministry of Tourism’s National Community Tourism Policy and Strategy aimed at developing community tourism island-wide to diversify the island’s tourism product.

Minister Bartlett said it would serve as a pilot project for community tourism, adding that he hoped it could be replicated across the island.

The facility financed by the Tourism Enhancement Fund (TEF), serves as counterpart funding for the Compete Caribbean Initiative which has committed some US $627,000 to date, to develop community tourism in the area.

The loan scheme is being administered by Jamaica National Small Business Loans (JNSBL). Applicants will be able to access loans of up to J $2 million (US $15,773) at a highly subsidised interest rate of 3 per cent per annum for five years. Several small business operators present at the launch last week signed loan applications on the spot.

Minister Bartlett said the scheme would enable the enterprises in Treasure Beach to become compliant and more appealing, which he said is crucial to positioning the area as a unique destination offering a “rustic luxury experience which the rich and famous seek when they want to escape from the formal luxurious settings that are characteristic of some of the destinations that we know, where the link with nature is never broken but the quality of the creature comforts are still at the highest level.”

In anticipation of increased tourist traffic, roads in Treasure Beach are to be improved and consideration given to offering air travel to the south coast by upgrading the Lionel Densham Aerodrome. ~ Caribbean360 ~

The elegance of Quince Duncan: a chat with the celebrated writer

NATASHA GORDON-CHIPEMBERE | 2 DAYS AGO

Quince Duncan at Casa Presidencial, August 2016. Erin Skoczylas/The Tico Times

About six years ago, when I was a just novice getting my feet wet in research about slavery in colonial Costa Rica, I managed to get an interview with the renowned writer Quince Duncan. Born in 1940 in San José, don Quince is celebrated as Costa Rica’s first Afro-Caribbean writer in the Spanish language. His literary production is prolific: he has written and co-authored over 40 books, including “Hombres Curtidos,” “Kimbo,” “El Pueblo Afrodescendiente,” “Un Señor de Chocolate,” “Los cuatro espejos” and “La Paz del pueblo.” His novel “A Message from Rosa” is written in English and Spanish.

His work focuses on the Afro-Caribbean population living on Costa Rica’s Caribbean coast, particularly around the city of Puerto Limón, though his current writing focuses on the indigenous populations in Costa Rica.

His novels and short stories have been awarded Costa Rica’s National Literature Prize and the Costa Rican Editorial Prize. A growing number of global scholars writing on AfroLatin@s are clamoring for more work by Duncan in English, and scholarly texts have explored his considerable contributions to the canon, including Dorothy Mosby’s “Quince Duncan: Writing Afro-Costa Rican and Caribbean Identity” and Dellita Martin-Ogunsola’s “The Eve/Hagar Paradigm in the Fiction of Quince Duncan.”

My initial interview with don Quince took place six years ago when I was visiting family over the Christmas holidays. It was my first solo venture in a bus and taxi in Costa Rica, from Quesada Durán in Zapote to don Quince’s house in Heredia, and I struggled with the directions – which, of course, included something like “500 meters to the house with the brown fence, then 200 meters to the pulperia.” Eventually, I got there accompanied by several neighborhood dogs. The night before I had spoken to my Costa Rican mother in New York, telling her how excited I was to meet the famous writer. She stopped me in mid-sentence, asking what I knew about him. Little had I known that my mother knew don Quince through the Anglican Church in Siquirres, Limón, in the 1960s. Having this connection felt like a blessing when I finally arrived at his door.

I have always felt the elegance of Quince Duncan, from that first meeting when he allowed me to quiz him on Costa Rican history and his writing practice. I cringe now at the uninformed questions I must have asked – I’m not searching for that tape recording anytime soon – but the amount that I learned has made me see him as a “padrino” and a mentor. Because of his fifty-plus years of dedicated literary production and human rights activism, Quince Duncan is truly Costa Rica’s national treasure. (My question is, who from the younger generation will support his current work and keep the torch going? I am ready to volunteer!)

Now, six years later, we are long familiars, and I had a chance to sit down with him again this month. As the new Commissioner of the Ministry of Afro-Costa Rican Affairs, don Quince invited me to his office at the Casa Presidencial, where we discussed the state of Afro-Costa Rican affairs and his current writing projects. I also had the chance to congratulate him on the President’s Award he was given on June 4 in St. Martin at their 14th Annual Book Fair.

Excerpts follow.

Please share the current writing projects that you are involved in.

I am working on a collection of three short stories about the indigenous populations in Limón, focusing on the Matina Rebellion against the Europeans; the last Chief of the Talamanca region who was poisoned when he was vocal against the United Fruit Company; and lastly, the rebellion in Talamanca where the Europeans could not conquer the city. This collection is expected to be published at the end of 2016. The next novel is about the rebellion “de color,” by people of color during the Revolution in Cuba.

Some additional good news is that the University of Alabama may be publishing translations of two of my published novels. Lastly, I am working on a large project about the culture and history of Afro-descended populations in Latin America which is expected to be part of the AfroLatin@ Diasporas Book Series by Palgrave in the United States that should be out by late 2017.

The Ministry of Afro-Costa Ricans Affairs was established last year as part of the United Nation’s Decade of the Afro-Descendants. How did this come to pass?

The Office was set up at the request of the Costa Rican Afro-descended population during the campaign of [President Luis Guillermo Solís] and came to fruition in February 2015. Right now the Ministry has 17 goals that we hope can get accomplished by 2018.

What are the major initiatives of your office?

With the Ministry of Health, we have established a health protocol to focus a health initiative for Afro-descended populations who have historically been left out of the general social services in Costa Rica. We are targeting populations where we find concentrations of diseases such as glaucoma, which has a higher prevalence rate in people of African descent. We found higher concentrations in the people of Guanacaste than in Limón, which confirms that area had a large heritage of Afro-descendants starting from the 16th century. Within this initiative we are trying to create programs that are also culturally sensitive so that patients and doctors can communicate better. This program should be up and running by April 2017.

My office is also initiating an English-language program in Limón that will be funded by the National Learning Institute (INA). The goal is to train 2,000 people in English within 18 months. This project seeks not only to restore the use of English in this community but also to prepare for the new port that is being built in Moin, which promises jobs that require English. We are in partnership with the University of Costa Rica and other institutions where these courses can be offered. We are also working on the formal recognition of Creole English in Limón as part of the cultural and linguistic heritage of the community.

Through a process of working with local Black organizations in Limón, 170 young people have been identified to begin a skills training program that they can take alongside their high-school courses. Some of these young people are also outside the school system and are being supported so that they can get employment. This program is being co-sponsored by the Ministry of Labor and Finance.

Can you tell me about your work on the issue of racism?

Along with Dr. Rina Caceres and several others, I have begun a program of racial sensitivity training and workshops for the judiciary system, the police force and other policy makers. Once a month, regional activities around racism are being conducted. What we have found is that the need for information is so great that we are creating a course on a CD with an additional booklet that can be used in any professional setting for this type of training, as there are too few people doing this necessary work.

What I have found in these workshops is that most Ticos are unaware that they hold racist tendencies. Once they gain knowledge of this, they are open to self-reflect and do the work that will make the country more inclusive.

Once of the outstanding take-aways in some of these workshops is that many Ticos do not recognize what racism actually is. They have seen the public markers of racism in South African Apartheid or the Jim Crow Laws of the Southern United States. Signs that separated races were clearly racist. Since these public signposts were not used in Costa Rica, people automatically assumed there was no racism here and so, for instance, they cannot understand why “Cocori” is an offensive book to the Afro-Costa Rican population. These workshops opened up these types of radical, honest discussions.

Read more from Natasha Gordon-Chipembere here.

Natasha Gordon-Chipembere holds a PhD in English. She is a writer, professor and founder of the Tengo Sed Writers Retreats. In June 2014, she moved to Heredia, Costa Rica with her family from New York. She may be reached at indisunflower@gmail.com. Her column “Musings from an Afro-Costa Rican” is published monthly.

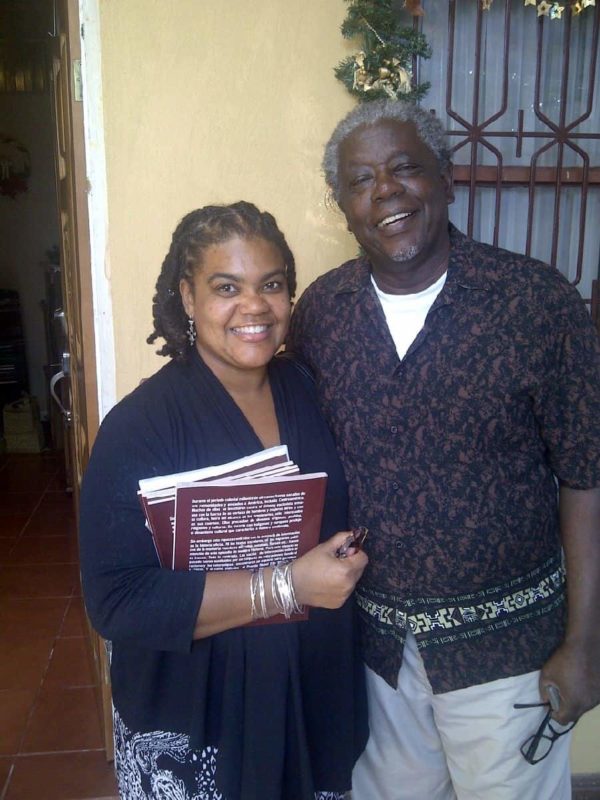

Natasha Gordon-Chipembere with Quince Duncan. Natasha Gordon-Chipembere/The Tico Times

The elegance of Quince Duncan: a chat with the celebrated writer

NATASHA GORDON-CHIPEMBERE | 2 DAYS AGO

Quince Duncan at Casa Presidencial, August 2016. Erin Skoczylas/The Tico Times

About six years ago, when I was a just novice getting my feet wet in research about slavery in colonial Costa Rica, I managed to get an interview with the renowned writer Quince Duncan. Born in 1940 in San José, don Quince is celebrated as Costa Rica’s first Afro-Caribbean writer in the Spanish language. His literary production is prolific: he has written and co-authored over 40 books, including “Hombres Curtidos,” “Kimbo,” “El Pueblo Afrodescendiente,” “Un Señor de Chocolate,” “Los cuatro espejos” and “La Paz del pueblo.” His novel “A Message from Rosa” is written in English and Spanish.

His work focuses on the Afro-Caribbean population living on Costa Rica’s Caribbean coast, particularly around the city of Puerto Limón, though his current writing focuses on the indigenous populations in Costa Rica.

His novels and short stories have been awarded Costa Rica’s National Literature Prize and the Costa Rican Editorial Prize. A growing number of global scholars writing on AfroLatin@s are clamoring for more work by Duncan in English, and scholarly texts have explored his considerable contributions to the canon, including Dorothy Mosby’s “Quince Duncan: Writing Afro-Costa Rican and Caribbean Identity” and Dellita Martin-Ogunsola’s “The Eve/Hagar Paradigm in the Fiction of Quince Duncan.”

My initial interview with don Quince took place six years ago when I was visiting family over the Christmas holidays. It was my first solo venture in a bus and taxi in Costa Rica, from Quesada Durán in Zapote to don Quince’s house in Heredia, and I struggled with the directions – which, of course, included something like “500 meters to the house with the brown fence, then 200 meters to the pulperia.” Eventually, I got there accompanied by several neighborhood dogs. The night before I had spoken to my Costa Rican mother in New York, telling her how excited I was to meet the famous writer. She stopped me in mid-sentence, asking what I knew about him. Little had I known that my mother knew don Quince through the Anglican Church in Siquirres, Limón, in the 1960s. Having this connection felt like a blessing when I finally arrived at his door.

I have always felt the elegance of Quince Duncan, from that first meeting when he allowed me to quiz him on Costa Rican history and his writing practice. I cringe now at the uninformed questions I must have asked – I’m not searching for that tape recording anytime soon – but the amount that I learned has made me see him as a “padrino” and a mentor. Because of his fifty-plus years of dedicated literary production and human rights activism, Quince Duncan is truly Costa Rica’s national treasure. (My question is, who from the younger generation will support his current work and keep the torch going? I am ready to volunteer!)

Now, six years later, we are long familiars, and I had a chance to sit down with him again this month. As the new Commissioner of the Ministry of Afro-Costa Rican Affairs, don Quince invited me to his office at the Casa Presidencial, where we discussed the state of Afro-Costa Rican affairs and his current writing projects. I also had the chance to congratulate him on the President’s Award he was given on June 4 in St. Martin at their 14th Annual Book Fair.

Excerpts follow.

Please share the current writing projects that you are involved in.

I am working on a collection of three short stories about the indigenous populations in Limón, focusing on the Matina Rebellion against the Europeans; the last Chief of the Talamanca region who was poisoned when he was vocal against the United Fruit Company; and lastly, the rebellion in Talamanca where the Europeans could not conquer the city. This collection is expected to be published at the end of 2016. The next novel is about the rebellion “de color,” by people of color during the Revolution in Cuba.

Some additional good news is that the University of Alabama may be publishing translations of two of my published novels. Lastly, I am working on a large project about the culture and history of Afro-descended populations in Latin America which is expected to be part of the AfroLatin@ Diasporas Book Series by Palgrave in the United States that should be out by late 2017.

The Ministry of Afro-Costa Ricans Affairs was established last year as part of the United Nation’s Decade of the Afro-Descendants. How did this come to pass?

The Office was set up at the request of the Costa Rican Afro-descended population during the campaign of [President Luis Guillermo Solís] and came to fruition in February 2015. Right now the Ministry has 17 goals that we hope can get accomplished by 2018.

What are the major initiatives of your office?

With the Ministry of Health, we have established a health protocol to focus a health initiative for Afro-descended populations who have historically been left out of the general social services in Costa Rica. We are targeting populations where we find concentrations of diseases such as glaucoma, which has a higher prevalence rate in people of African descent. We found higher concentrations in the people of Guanacaste than in Limón, which confirms that area had a large heritage of Afro-descendants starting from the 16th century. Within this initiative we are trying to create programs that are also culturally sensitive so that patients and doctors can communicate better. This program should be up and running by April 2017.

My office is also initiating an English-language program in Limón that will be funded by the National Learning Institute (INA). The goal is to train 2,000 people in English within 18 months. This project seeks not only to restore the use of English in this community but also to prepare for the new port that is being built in Moin, which promises jobs that require English. We are in partnership with the University of Costa Rica and other institutions where these courses can be offered. We are also working on the formal recognition of Creole English in Limón as part of the cultural and linguistic heritage of the community.

Through a process of working with local Black organizations in Limón, 170 young people have been identified to begin a skills training program that they can take alongside their high-school courses. Some of these young people are also outside the school system and are being supported so that they can get employment. This program is being co-sponsored by the Ministry of Labor and Finance.

Can you tell me about your work on the issue of racism?

Along with Dr. Rina Caceres and several others, I have begun a program of racial sensitivity training and workshops for the judiciary system, the police force and other policy makers. Once a month, regional activities around racism are being conducted. What we have found is that the need for information is so great that we are creating a course on a CD with an additional booklet that can be used in any professional setting for this type of training, as there are too few people doing this necessary work.

What I have found in these workshops is that most Ticos are unaware that they hold racist tendencies. Once they gain knowledge of this, they are open to self-reflect and do the work that will make the country more inclusive.

Once of the outstanding take-aways in some of these workshops is that many Ticos do not recognize what racism actually is. They have seen the public markers of racism in South African Apartheid or the Jim Crow Laws of the Southern United States. Signs that separated races were clearly racist. Since these public signposts were not used in Costa Rica, people automatically assumed there was no racism here and so, for instance, they cannot understand why “Cocori” is an offensive book to the Afro-Costa Rican population. These workshops opened up these types of radical, honest discussions.

Read more from Natasha Gordon-Chipembere here.

Natasha Gordon-Chipembere holds a PhD in English. She is a writer, professor and founder of the Tengo Sed Writers Retreats. In June 2014, she moved to Heredia, Costa Rica with her family from New York. She may be reached at indisunflower@gmail.com. Her column “Musings from an Afro-Costa Rican” is published monthly.

Natasha Gordon-Chipembere with Quince Duncan. Natasha Gordon-Chipembere/The Tico Times

The elegance of Quince Duncan: a chat with the celebrated writer

Red Shield

Global Domination

Its about to be dark days ahead for Afro-Brazilians.

at that one tweet talkin bout the usa should send help. shyt wouldn't be surprised if the usa helped this "coup"

at that one tweet talkin bout the usa should send help. shyt wouldn't be surprised if the usa helped this "coup"Dominicans: Haiti Gov’t will remove restrictions on 23 products

Wednesday August 31, 2016

Dominican Republic, Economy, Executive

Samuel Maxime

Editor-in-Chief

PORT-AU-PRINCE, Haiti (sentinel.ht) – Dominican news agencies are reporting that the Haitian government has agreed to lift the import restrictions placed on 23 Dominican products since September 2015. Haitian authorities had reported on their meeting with the new Dominican Minister of Foreign Affairs, Tuesday, but made no announcement of any such regarding a lifting of the import ban.

According to the Dominican news agency, Hoy, the Haitian Minister of Foreign Affairs, Pierrot Delienne, will only require that custom duties be paid by land importers – which has always been the law but enforcement debated – and that the Haitian government will have until late October to document 112,000 nationals living in the Dominican Republic. These nationals would be eligible for citizenship under the Dominican National Plan for the Regulation of Immigrants but did not have vital documents to apply before the July 2015 deadline.

Hoy reports that it was at a meeting away from the National Palace and at the Hotel El Rancho, near the Dominican Embassy in Port-au-Prince, that Minister Vargas raised with his Haitian counterpart and the authorities of Haiti, a treaty to energize the flow of bilateral trade “unhindered and without objections” beyond those imposed by international trade rules.

“Let us propose, Mr. Chancellor, to meet periodically, to restore the tasks of the Joint Bilateral Commission for this handshake I offer you is always reminder sign of how sincere are these expressions of friendship, respect and good neighborly relations with Haiti” said the Dominican Minister.

Vargas was accompanied by Dominican entrepreneurs Juan Vicini, Manuel Estrella and Fernando Capellan, the Dominican Ambassador to Haiti, Ruben Silié, as well as officials and diplomats from the Dominican Foreign Ministry.

He said that both the Dominican Republic and Haiti must put aside what disengages them and undertake an action agenda from the points which should underpin a true friendship, which open the way to new ideas of trade and cultural relations, respecting their individual characteristics.

Vargas noted that mutual trust is essential, so that both sides should work on clear rules governing trade and investment guarantee, with efficient mechanisms that allow collision bypass routes.

Dominican Foreign Minister said that the existence of synergies is clear, as has been demonstrated with companies labor intensive that have settled in the north Haitian Dominican capital.

Vargas suggested combining best practices from both countries, ensuring that the Dominican side there is a genuine interest in working “shoulder to shoulder” with them.

In his view, the two countries should discuss important agreements, based on the mutual recognition of sanitary and phytosanitary measures and the application of tariff measures to facilitate the areas of services and transport in Haiti.

He argued that the purpose of his visit is to hold a frank and sincere dialogue, in which the similarities greatly outweigh the differences, and it was no coincidence have chosen Haiti as the first country to visit in the newly inaugurated leadership of the Ministry of External relationships.

He said that the Dominican Republic has taken the relentless pursuit of freedom as inalienable cause, “and opposed to foreign interference sovereign vocation of peoples who have experienced firsthand the tragedy of imperial ambitions”, referring to diversity, “more a pitfall, is a factor that adds richness and variety to this side of the Caribbean, whose tourism potential is not yet fully developed.“

Dominicans: Haiti Gov’t will remove restrictions on 23 products

Wednesday August 31, 2016

Dominican Republic, Economy, Executive

Samuel Maxime

Editor-in-Chief

PORT-AU-PRINCE, Haiti (sentinel.ht) – Dominican news agencies are reporting that the Haitian government has agreed to lift the import restrictions placed on 23 Dominican products since September 2015. Haitian authorities had reported on their meeting with the new Dominican Minister of Foreign Affairs, Tuesday, but made no announcement of any such regarding a lifting of the import ban.

According to the Dominican news agency, Hoy, the Haitian Minister of Foreign Affairs, Pierrot Delienne, will only require that custom duties be paid by land importers – which has always been the law but enforcement debated – and that the Haitian government will have until late October to document 112,000 nationals living in the Dominican Republic. These nationals would be eligible for citizenship under the Dominican National Plan for the Regulation of Immigrants but did not have vital documents to apply before the July 2015 deadline.

Hoy reports that it was at a meeting away from the National Palace and at the Hotel El Rancho, near the Dominican Embassy in Port-au-Prince, that Minister Vargas raised with his Haitian counterpart and the authorities of Haiti, a treaty to energize the flow of bilateral trade “unhindered and without objections” beyond those imposed by international trade rules.

“Let us propose, Mr. Chancellor, to meet periodically, to restore the tasks of the Joint Bilateral Commission for this handshake I offer you is always reminder sign of how sincere are these expressions of friendship, respect and good neighborly relations with Haiti” said the Dominican Minister.

Vargas was accompanied by Dominican entrepreneurs Juan Vicini, Manuel Estrella and Fernando Capellan, the Dominican Ambassador to Haiti, Ruben Silié, as well as officials and diplomats from the Dominican Foreign Ministry.

He said that both the Dominican Republic and Haiti must put aside what disengages them and undertake an action agenda from the points which should underpin a true friendship, which open the way to new ideas of trade and cultural relations, respecting their individual characteristics.

Vargas noted that mutual trust is essential, so that both sides should work on clear rules governing trade and investment guarantee, with efficient mechanisms that allow collision bypass routes.

Dominican Foreign Minister said that the existence of synergies is clear, as has been demonstrated with companies labor intensive that have settled in the north Haitian Dominican capital.

Vargas suggested combining best practices from both countries, ensuring that the Dominican side there is a genuine interest in working “shoulder to shoulder” with them.

In his view, the two countries should discuss important agreements, based on the mutual recognition of sanitary and phytosanitary measures and the application of tariff measures to facilitate the areas of services and transport in Haiti.

He argued that the purpose of his visit is to hold a frank and sincere dialogue, in which the similarities greatly outweigh the differences, and it was no coincidence have chosen Haiti as the first country to visit in the newly inaugurated leadership of the Ministry of External relationships.

He said that the Dominican Republic has taken the relentless pursuit of freedom as inalienable cause, “and opposed to foreign interference sovereign vocation of peoples who have experienced firsthand the tragedy of imperial ambitions”, referring to diversity, “more a pitfall, is a factor that adds richness and variety to this side of the Caribbean, whose tourism potential is not yet fully developed.“

Dominicans: Haiti Gov’t will remove restrictions on 23 products

How Three Caribbean Restaurants Help Keep Brooklyn’s Island Pride Strong

The people behind Gloria’s, Veggies, and Peppa’s on how they’ve made the borough a home away from home.

By NYLE DANIELS

Photographer PAUL MCLAREN

Brooklyn is filled to capacity with hundreds of places to eat. Sometimes, finding a unique place to dine here can be a scavenger hunt in itself. But what sets Brooklyn apart from neighboring boroughs is the prevalent, interdependent Caribbean culture that exists in areas such as Crown Heights and East Flatbush. In fact, the heavy Caribbean presence that has existed here since the late '60s solidifies Brooklyn's reputation as a cultural — and culinary — force. Anyone who's visited Flatbush or Crown Heights knows what I'm talking about: thick smoke floating from jerk chicken being barbecued on a grill, constant horn-squeaks from dollar cab drivers hounding for a fare, Beres Hammond and Sanchez tracks playing outside of tiny, closet-sized storefronts year round.

But if you've been to Brooklyn and never tasted Caribbean cuisine from some of its landmark spots, then you've already played yourself. Still, the hometown heroes who run restaurants, new and old, contribute more than just a plate a food to Brooklyn — they are a part of its past, present, and future. As neighborhoods throughout the borough undergo various phases of gentrification, The FADER spoke to the people behind Gloria's, Veggies, and Peppa's about their work and how they preserve their culture and embrace Caribbean pride.

Read their stories below.

1. Gloria's Caribbean Cuisine

764 Nostrand Ave, Crown Heights

BRYAN CUMBERBATCH: Gloria’s is a family business —I was actually born into it. My grandmother, she is Gloria. She came here from Trinidad in '73. The business has been up since 1974. When Gloria's was first opened, she wanted to start a legacy — which she did — and since I'm the new generation, I have to keep that up. Growing up, I'd see her work real hard; on her feet for 15, 16, 17 hours a day, at sixty-something years old. She was still going hard; she's my biggest role model. I can't see this place go down — no way. When I get older, I already intend to pass this down to my kids, show them how it's done. I already had them start [cooking], to know what it is to "work." Everything in life, you gotta work for — to get where you gotta go. And nothing comes easy, that's how I was raised. Hard work pays off.

There is no average day here. As soon as lunch, 12 p.m., 1 o'clock hits, it's a mad house. It's like you're working out in the gym for, like, ten hours. Sometimes, I have to run away from here to catch a little breath. But doing it for all this time, I love it, I'm used to it. I love what I do. Some people who are in it might say, "It's hard work, long hours." If you're your own boss, you gotta make your own time, you have to set your own standards. I'm a family man, married for fourteen years, four kids. I hear it from my wife all the time, "Babe, you not coming with us?" But she knows, my family knows, we have a goal to accomplish, That's what I love about my family — they always back me up, especially my wife and my aunt. We got a job to do, and we just do it.

One thing we don't worry about is competition. For us being here for so many years, we don't even think about that. “Caribbean Brooklyn” — we try to keep it strong on this side, to have the culture remain in the neighborhood, because we see many restaurants: they open, and they close, and they don't last too long. It's how you do your business. The amount of years we've been here, and the kind of feedback we get from people, it makes us feel like we’re doing something right. It's not, "If we like it, the people like it." It’s not about what we think, it's about what the people think. There's not just "one kind" of people out here. We show everybody love, everybody comes and eats. We attend to them, we make them feel comfortable when they come here. Whatever they want, we go out and try to satisfy.

We have plenty of regulars that come in and spend hundreds of dollars — especially on the catering orders. We have a few celebs that we've dealt with. One is Beyoncé, she loves our oxtails. Anytime she comes to New York, she always sends someone to get it. I am family with Inga [Foxy Brown], that's my second blood. She's a big client here. Me and her practically grew up in the same house together. Anthony Bourdain, we did a show with him, No Reservations. Michael K. Williams, he's another very good customer of ours. He's local, he's always around here. I know when he's in New York, I know this is where he comes to grab something to eat. There's a few other [celebs], but you know, they always stay disguised. But we know it's them, they say hi and keep it moving.

When customers come in, they're like, "Oh, you guys have Apple Pay?" Yeah, because you gotta keep up or you'll get left behind. I plan to do an internet cooking show. That's coming out around Christmas time. But a main goal for myself is to open up a culinary school for kids — because even my daughters, they like to get up and cook. Every time I'm cooking, they're like, "Daddy, what's this?" or "Daddy, what's that?" I know that there are kids out there that want to learn, but sometimes the environment they're in, they're trapped. When I do open that culinary school one day and, say, the parents don't have enough money to afford it, trust me, I'll find a way for that kid to get in there. He or she can learn something. It wouldn't be just one kind of food, I'll have a variety of foods to learn. I'll call an African chef, a West Indian chef, an Italian chef, and it would be the foods you like to learn. But that's my goal — to open a Gloria's Cooking School.

2. Veggies Natural Juice Bar

785 Franklin Ave, Crown Heights

JAHMAN MCKENZIE: My mother and I opened this place up six years ago. She had a dream. She wanted to do a sit-in cafe type of place you could be comfortable to drink your tea. My uncle had a juice bar up in the Bronx, and so that's what sprung her to do this. Juicing is like a way of life; all of this is natural eating and drinking. My mom used to always make smoothies with us on Sunday dinner. She always had the ingredients. The healthy eating and vegan lifestyle, that still is my father. What is called "vegan" eating, we called "Ital" since the '60s. Now we see vegan becoming popular, when Ital always was part of our culture for years.

We get over a hundred transactions a day. You got your customers, then you got your loyal customers, and then you have the customers that love you, and then you got the customers that come when they can, when they can afford to because you know this is an expensive habit if you're doing it daily. And then you always have your visitors, your guests. It's a lifestyle, it's an investment, but an investment on your health. You'd go out and buy breakfast somewhere else, why not just buy a healthy smoothie? But a good customer, you become friends with that person. I have customers that have their own drinks on the [menu] wall. They were just "in it" with us. They spent their bread, daily, weekly. They would come and get their own recipes or try out new things, and getting it over and over again, I'm like, "You know what,throw this on the wall, throw that on the wall." They stick with us, they recommend us to people, talk highly of us. They're definitely up in it, with us. They're a part of the family, so to speak.

The people behind Gloria’s, Veggies, and Peppa’s on how they’ve made the borough a home away from home.

By NYLE DANIELS

Photographer PAUL MCLAREN

Brooklyn is filled to capacity with hundreds of places to eat. Sometimes, finding a unique place to dine here can be a scavenger hunt in itself. But what sets Brooklyn apart from neighboring boroughs is the prevalent, interdependent Caribbean culture that exists in areas such as Crown Heights and East Flatbush. In fact, the heavy Caribbean presence that has existed here since the late '60s solidifies Brooklyn's reputation as a cultural — and culinary — force. Anyone who's visited Flatbush or Crown Heights knows what I'm talking about: thick smoke floating from jerk chicken being barbecued on a grill, constant horn-squeaks from dollar cab drivers hounding for a fare, Beres Hammond and Sanchez tracks playing outside of tiny, closet-sized storefronts year round.

But if you've been to Brooklyn and never tasted Caribbean cuisine from some of its landmark spots, then you've already played yourself. Still, the hometown heroes who run restaurants, new and old, contribute more than just a plate a food to Brooklyn — they are a part of its past, present, and future. As neighborhoods throughout the borough undergo various phases of gentrification, The FADER spoke to the people behind Gloria's, Veggies, and Peppa's about their work and how they preserve their culture and embrace Caribbean pride.

Read their stories below.

1. Gloria's Caribbean Cuisine

764 Nostrand Ave, Crown Heights

BRYAN CUMBERBATCH: Gloria’s is a family business —I was actually born into it. My grandmother, she is Gloria. She came here from Trinidad in '73. The business has been up since 1974. When Gloria's was first opened, she wanted to start a legacy — which she did — and since I'm the new generation, I have to keep that up. Growing up, I'd see her work real hard; on her feet for 15, 16, 17 hours a day, at sixty-something years old. She was still going hard; she's my biggest role model. I can't see this place go down — no way. When I get older, I already intend to pass this down to my kids, show them how it's done. I already had them start [cooking], to know what it is to "work." Everything in life, you gotta work for — to get where you gotta go. And nothing comes easy, that's how I was raised. Hard work pays off.

There is no average day here. As soon as lunch, 12 p.m., 1 o'clock hits, it's a mad house. It's like you're working out in the gym for, like, ten hours. Sometimes, I have to run away from here to catch a little breath. But doing it for all this time, I love it, I'm used to it. I love what I do. Some people who are in it might say, "It's hard work, long hours." If you're your own boss, you gotta make your own time, you have to set your own standards. I'm a family man, married for fourteen years, four kids. I hear it from my wife all the time, "Babe, you not coming with us?" But she knows, my family knows, we have a goal to accomplish, That's what I love about my family — they always back me up, especially my wife and my aunt. We got a job to do, and we just do it.

One thing we don't worry about is competition. For us being here for so many years, we don't even think about that. “Caribbean Brooklyn” — we try to keep it strong on this side, to have the culture remain in the neighborhood, because we see many restaurants: they open, and they close, and they don't last too long. It's how you do your business. The amount of years we've been here, and the kind of feedback we get from people, it makes us feel like we’re doing something right. It's not, "If we like it, the people like it." It’s not about what we think, it's about what the people think. There's not just "one kind" of people out here. We show everybody love, everybody comes and eats. We attend to them, we make them feel comfortable when they come here. Whatever they want, we go out and try to satisfy.

We have plenty of regulars that come in and spend hundreds of dollars — especially on the catering orders. We have a few celebs that we've dealt with. One is Beyoncé, she loves our oxtails. Anytime she comes to New York, she always sends someone to get it. I am family with Inga [Foxy Brown], that's my second blood. She's a big client here. Me and her practically grew up in the same house together. Anthony Bourdain, we did a show with him, No Reservations. Michael K. Williams, he's another very good customer of ours. He's local, he's always around here. I know when he's in New York, I know this is where he comes to grab something to eat. There's a few other [celebs], but you know, they always stay disguised. But we know it's them, they say hi and keep it moving.

When customers come in, they're like, "Oh, you guys have Apple Pay?" Yeah, because you gotta keep up or you'll get left behind. I plan to do an internet cooking show. That's coming out around Christmas time. But a main goal for myself is to open up a culinary school for kids — because even my daughters, they like to get up and cook. Every time I'm cooking, they're like, "Daddy, what's this?" or "Daddy, what's that?" I know that there are kids out there that want to learn, but sometimes the environment they're in, they're trapped. When I do open that culinary school one day and, say, the parents don't have enough money to afford it, trust me, I'll find a way for that kid to get in there. He or she can learn something. It wouldn't be just one kind of food, I'll have a variety of foods to learn. I'll call an African chef, a West Indian chef, an Italian chef, and it would be the foods you like to learn. But that's my goal — to open a Gloria's Cooking School.

2. Veggies Natural Juice Bar

785 Franklin Ave, Crown Heights

JAHMAN MCKENZIE: My mother and I opened this place up six years ago. She had a dream. She wanted to do a sit-in cafe type of place you could be comfortable to drink your tea. My uncle had a juice bar up in the Bronx, and so that's what sprung her to do this. Juicing is like a way of life; all of this is natural eating and drinking. My mom used to always make smoothies with us on Sunday dinner. She always had the ingredients. The healthy eating and vegan lifestyle, that still is my father. What is called "vegan" eating, we called "Ital" since the '60s. Now we see vegan becoming popular, when Ital always was part of our culture for years.

We get over a hundred transactions a day. You got your customers, then you got your loyal customers, and then you have the customers that love you, and then you got the customers that come when they can, when they can afford to because you know this is an expensive habit if you're doing it daily. And then you always have your visitors, your guests. It's a lifestyle, it's an investment, but an investment on your health. You'd go out and buy breakfast somewhere else, why not just buy a healthy smoothie? But a good customer, you become friends with that person. I have customers that have their own drinks on the [menu] wall. They were just "in it" with us. They spent their bread, daily, weekly. They would come and get their own recipes or try out new things, and getting it over and over again, I'm like, "You know what,throw this on the wall, throw that on the wall." They stick with us, they recommend us to people, talk highly of us. They're definitely up in it, with us. They're a part of the family, so to speak.