You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Essential Afro-Latino/ Caribbean Current Events

- Thread starter Poitier

- Start date

More options

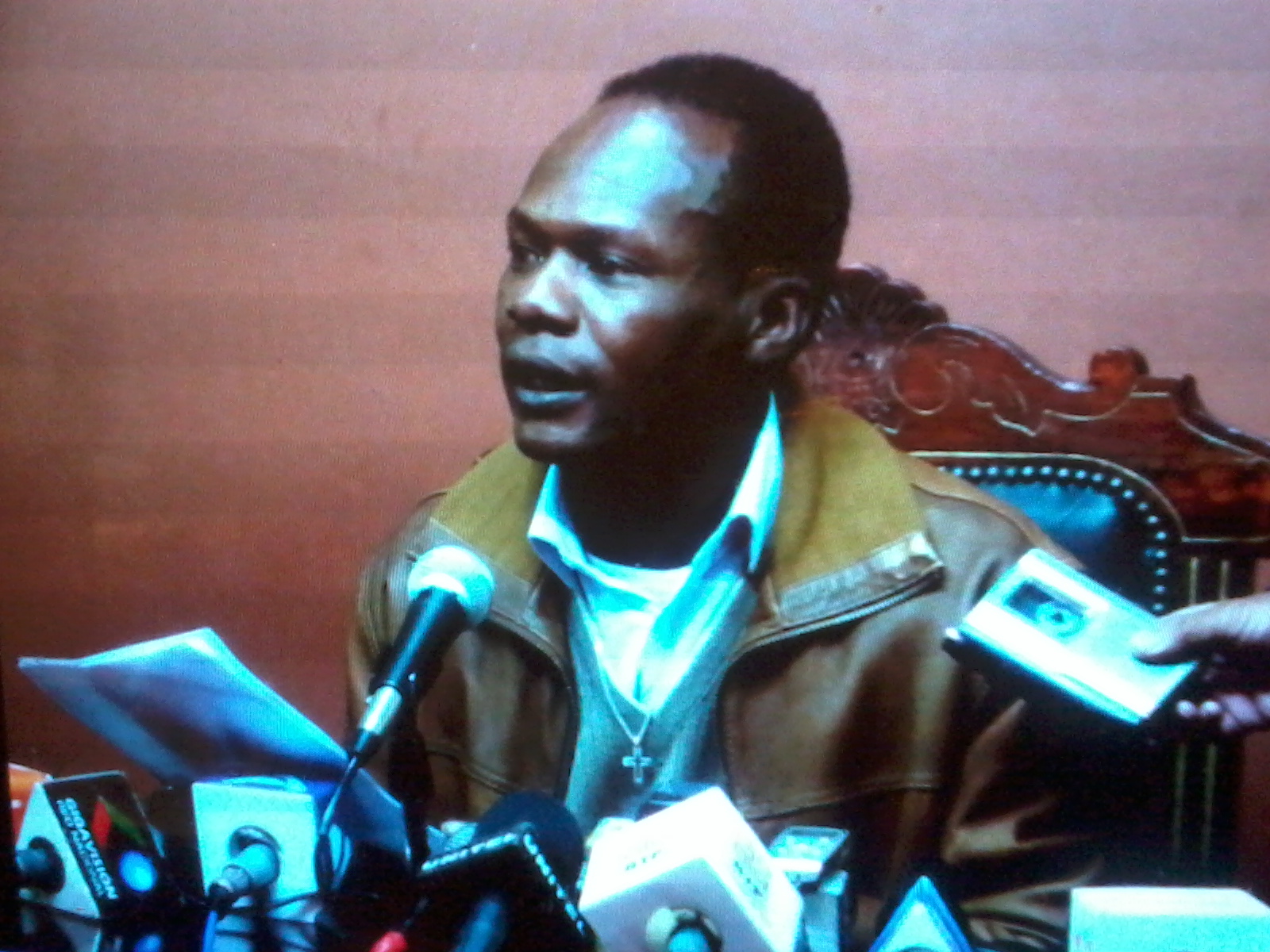

Who Replied?Nigeria’s most reclusive Billionaire,Oluwo Antonio Deinde Fernandez.

Welcome to the world of one of Africa’s richest men: HIS EXCELLENCY, OLUWO ANTONIO OLADEINDE FERNANDEZ, Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary Permanent Representative to the United Nations.

When it comes to the most impressive and exuberant display of the splendour of wealth, Fernandez dusts them all -by miles. The name ‘Fernandez’ is Portuguese in origin and shows that he is of the popular Fernandez family of Lagos. Historical accounts show that the Fernandezes were originally descendants of freed slaves from Brazil, where Portuguese is the official language. Some of the first modern-styled buildings in Lagos were built by the Fernandezes, and these buildings are known for their spectacular Brazilian architecture. Portuguese navigators were also the first European explorers to reach Lagos State. Actually, they gave the state the name ‘Lagos.

For Ovation magazine to feature a man in 40 pages says a lot about his prestigious standing. Very secretive (not in a bad way or let me say he guards his privacy jealously) and aloof (he very rarely comes to Nigeria where he is from), this is one rich man in a class and mansion of his own -with no rivals but maybe a few big cats.His wealth has dazed and fazed many, and left even many more speechless. ANTONIO DEINDE FERNANDEZ. Okay, enough of that. Let’s get some bits on him:

Even though he is Nigerian, he was appointed the Permanent Representative of Central African Republic (CAR) at the United Nations in 1997 (ain’t that classy?, but with the current turmoil in CAR, with former President Francois Bozize fleeing the nation, things are hazy). -Fernandez is said to have interests in the CAR’s oil industry (at a time, he was the Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Central African Republic). That does not include his bauxite (for aluminum) exports, gold mines (in Angola) and diamonds pits. He owns Petro Inett, an oil company. Petro Inett is just one of them. He also has shares in View, Sandcat Petroleum, Sanantonio, Goldfields, Voguehope, Grantdalem Inuola, Sandcat Goldfields (cat, cat, now I understand those two cats…lol), Woods and Petro Inett Equatorial Guinea.

-Before then, he had served as the Special Adviser to the President of Mozambique on International Economic Matters and from 1992-1995, he was the Ambassador-at-Large for the Republic of Togo and Angola.

-He was also once the Consul for Benin Republic (then Republic of Dahomey) (1966), made the Economic Advisor to the Angolan Government in 1982 (just for perspective, only Nigeria produces more oil than Angola in Africa, shey you gerrit?). To be specific, he was a long-time adviser to President José Eduardo dos Santos of Angola (he’s been ruling since 1975).

In 1984, he was the Ambassador and Deputy Permanent Representative of Mozambique to the United Nations. At a point, he was a Deputy Minister of Finance in Swaziland.

-He has houses in Kano, built a tower for himself in Lagos (where he was born in 1936), New York (where he is said to stay almost permanently), Scotland, France, Belgium and the United Kingdom. But that’s not all, he has accounts in the Cayman Islands, France, Switzerland (I love that country joor), Ireland, Hong Kong, Scotland and the United States. Don’t ask me of Nigeria.Also as 6 private jets.

He surrounds himself with the finest, classiest and the most exquisite things that money can buy. Do you know of any other moneybag who travels around in a convoy of pink Rolls Royces? Baba ni Deinde! (or wetin you think? Na my own opinion be this o, talk ya own!) And yes, if you have the misfortune (lol!) of entering a restaurant before him, you will have to vacate -unless maybe you are Bill Gates. His Excellency is said not to dine where there are commoners.

In a divorce case with one of his former wives, it was revealed that he splashed 200,000 British Pounds on his seven-storey townhouse to buy 1,000 books of gold leaf to ‘toosh’ up the already ‘tooshed’ cornices and balustrades. This man is just too much! 200,000 Pounds = N51 million naira. Not much, abi? It was also revealed by his former wife that in one of his houses in France, the wine collection (used in the wedding celebrations of their two daughters) alone is worth about $1 million (calm down, it’s just N160 million). Atimes, I cannot but just wonder about how the world is so so skewed in terms of wealth distribution. Some have more than they can ever spend or use, while some just manage to exist. Something somewhere is definitely wrong with humans, the so-called higher animals. Even animals do not have such wealth disparity. Well, it’s just a thought.

-A high chief of the Ogboni Confraternity, he is highly revered in his Yorubaland and his family motto is: Aguntan meji kii mumi ninu koto kan na (see images for the insignia). Okay, what that simply means is that two rams cannot drink from the same container. Or some people will say, there cannot be two captains on a ship. Well, that’s correct, there is no other Antonio Deinde Fernandez (the Big Masquerade). Today, he is married to a beauty from Kano State. Her name? Haleema, and has a daughter, Mahreyah. She is said to be of the Alhaji Muhammadu Maude (also known as Maude Tobacco) family of Kano. Alhaji Maude was the Presidential Liaison Officer for Kano State during the Shehu Shagari presidency. A wealthy businessman, he made attempts to become governor of Kano State in the 1980s but lost even though his campaign was one of the most colourful and was associated with the use of yan banga,local thugs.More to come.

Now you can see that dangote and the rest are learning.

chai!

The only black presidential candidate, Marina suffers resistance among Afro-Brazilians

Note from BW of Brazil: With black Brazilians being nearly invisible in Brazil’s sphere’s of power, one would think that the strong possibility of Marina Silva becoming the first black president in the nation’s history would have more feelings of hope and celebration within the Afro-Brazilian community. Well, this is not exactly how is looking for Silva. According to recent numbers, the incumbent president, Dilma Rouseff leads with 37% of the intended vote, while Marina carries 31% and Aécio Neves, 15%. But those same reports last week were predicting that once Aécio Neves dropped out of the race and Silva goes head to head with Rouseff, Silva would claim a victory. A report by Financial Times out today reveals that Silva and Rouseff would be in a tie without Neves in the race.

Breaking last week’s number down even further, we find that Dilma is the favorite among Catholics (40% to 31%), while Silva claims an edge (43% to 32%) with Evangelicals and a slight edge (32% to 30%) among persons of other religions. In terms of economic class, Dilma leads among Brazil’s poorest (49% to 27% among those earning one minimum salary per month and 38% to 33% among those who earn two minimum salaries), Marina leads among those who earn more than five minimum salaries (37% to 28%) while there is 35% tie between the two women in terms of people who earn between two and five minimum salaries per month.

Current President, Dilma Rouseff and candidate Marina Silva

We also see a sort of rich/poor break down in terms of support by education. For those who have up to a 4th grade education and between 5th and 8th grade, Dilma leads (50% to 25% and 44% to 29%, respectively) while Marina has the support of those who graduated from high school (38% to 33%) and those who graduated from college (37% to 24%). In terms of the racial question, numbers from late August and early September suggest that 40% of the Afro-Brazilian population intends to vote for Dilma versus 28% who intend to vote for Marina. These same reports show that the third candidate, Aécio Neves, would receive about 12% of the black vote, which is exactly the difference between Rouseff and Silva among this segment of the population. This could be a huge factor for either of the eventual two candidates, which will certainly be Silva and Rouseff.

According to research from TSE, PNAD/IBGE, the população negra (black population or the sum of pretos/blacks and pardos/browns) makes up 55% of qualified voters for the 2014 election, the first that this parcel of the population represents the majority. And as the black population represents the larger percentage of poor Brazilians, we can also see how, for the most part, race and class are also intimately linked in the upcoming election. In the past 12 years, under PT (Partido dos Trabalhadores or Workers Party) presidents Lula da Silva and Rouseff, the poor and black population made great gains in terms of access to higher education and ascension into the middle classes, which could explain why the black and poor seem to be remaining faithful to the possibility of Dilma’s re-election. This is part of the reason that this election cannot be simply seen as a racial vote with the population that looks more like Marina Silva voting for her based on identity politics. And there are a number of reasons for this.

Marina Silva lags behind incumbent President Dilma Rouseff in terms of black support

1) Even though racism, racial exclusion and white supremacy continue to reign supreme in Brazil, non-white people see this election, as always, as a chance to support the candidate that will most likely create policies in their interests. And with reputation of the PT connected to the struggle of “the people” (even with its rightward turn in recent years) and 12 years of economic improvement for this population, Dilma remains the favorite. 2) Racial numbers in Brazil can never been seen as absolute and cannot automatically be assumed that persons see themselves as others may seen them. What does it say for identity politics if we take note of a female who physically looks likes Marina Silva but sees defines herself as branca (white)? As there are millions of people in Brazil who would fit this phenotype, it would throw off the entire prediction.

3) In a clear difference in comparison with US President Barack Obama’s carrying of 95% of the African-American vote in the 2008 election, the dream of actually seeing a black president isn’t as strong a sentiment that could overcome other factors associated with quality of life and social ascension in Brazil. How else can one explain the fact that during his historic run for the presidency in 2008, Obama actually said very little about what he would do to improve the plight of black Americans and yet African-Americans overwhelmingly voted for him anyway. Sure, one would expect that in a country like Brazil in which the power structure is overwhelmingly white that non-whites would vote for someone who looked like them, but also remember that racial identity in Brazil is not as black and white as it is in the US. 4) There is an old saying in Brazil that even blacks don’t for blacks, thus, it is very likely that there are persons of visible African ancestry who would never vote for Marina regardless of how much she spoke to their interests.

5) Although Marina has identified herself as a black woman, her campaign as not as of yet spoken directly to concerns of black Brazilians, or better, persons of visible African descent. There are several key issues to consider in this issue. First, if she were to speak directly to the “black community” how many people would that actually be, as the vast majority of persons of visible African ancestry don’t actually define themselves asnegro/negra/black. Second, it is apparent that Marina, as any other candidate, must represent the wishes of the big money interests that are backing her. This clearly doesn’t apply to non-whites as they don’t represent big money, business interest nor political power. Although white supremacy is clearly visible in Brazil, because of a different history with less open racial conflict (despite the strong presence of racism/white supremacy), aspirations simply aren’t as tied directly to race in Brazil as they are in US. In fact, rather than seeing Marina as a female Obama, one could argue that in this election, President Rouseff may represent a figure closer to someone like a US President Lyndon Johnson in the minds of non-white Brazilians: a white political figure who is deemed to be in solidarity with an excluded parcel of the population is search of social ascension. And judging from the plight of African-Americans under nearly six years of the first black president, maybe it would be a good idea for Afro-Brazilians to analyze these candidates beyond the perspective of race.

The only black presidential candidate, Marina suffers resistance amongafrodescendentes (African descendants)

Activists and researchers of the black movement say that Marina has no ties to militancy

Marina is viewed with “suspicion” by blacks, academics, social organizations and activists. The more backward evangelical leaders of Brazil, like Malafaia and Feliciano, support her with force

by Ricardo Senra

“Brazilian nata, born in Rio Branco, Acre, on February 8, 1958, female, color/race preta(black) (1),” says the document from the Superior Electoral Court that formalizes Marina Silva’s candidacy for president.

In 2010, when she ran for the Planalto (quarters of Brazilian president) (2) for the first time, Marina said she wanted to be “the first black woman, from a poor background, President of the Federative Republic of Brazil.” Four years later, it appears, according to IBOPE, in the leader among intentions of white voters, but behind Dilma Rousseff among blacks and mulatos.

Despite being the only one of the three leading candidates to devote an entire chapter of her government program for the black population, the former senator is not perceived as a representative of that portion of the electorate.

Evangelical, daughter of mestiça (mixed race) mother and black father, Marina is analyzed with suspicion by academics, research institutes, social organizations and activists interviewed by BBC Brasil.

The most frequent criticisms question the candidate’s stance on issues important to black militancy. Freedom for religions of African origin, the land registry for quilombocommunities, viability of affirmative policies such as racial quotas, and the lack of links with the movement were the main points raised by respondents.

Paulino Cardoso, president of the Associação Brasileira de Pesquisadores Negros

“We are very happy that someone self-declares themselves black, but under no circumstances does Marina represent the struggle of this population,” says Professor Paulino Cardoso, president of the Associação Brasileira de Pesquisadores Negros (ABPN or Brazilian Association of Black Researchers) and researcher of Afro-Brazilian culture for 30 years.

“We [blacks] are the poorest of the poor in Brazil,” said Cardoso. “Will it be that the State streamlines what she promises, of neoliberal character, with an independent Banco Central (Central Bank) will able to fund our social policies? Blacks rely heavily on these initiatives, they cost more than R$12 billion (US$5.16 billion) for the government and are frowned upon by oligarchies,” says the professor.

Marina’s committee assured that the candidate would personally respond to questions sent by BBC on the subject by BBC Brasil. After cancelling the commitment twice, aides failed to respond to the report.

Allies

A PhD in psychology, Elisa Nascimento, president of Ipeafro (Instituto de Pesquisas e Estudos Afro Brasileiros or Research Institute of Afro Brazilian Studies), says that political allies of Marina can compromise her stance on religious tolerance.

To the press, Silva repeatedly said that she defends a “secular state”. The candidate, however, has the support of important Evangelical political leaders – such as the congressman Marco Feliciano (PSC-SP), who has said “to prophesy the burial of the pais de santo (Afro-Brazilian religion priests)” and the “closure of the terreiros de macumba.” (3)

“I have seen Marina try to unbind religion from her positions, but it is evident that her beliefs influence her political action. There are Neo-pentecostals who repeatedly disrespect the Candomblé and Umbanda (Afro-Brazilian religions). There are terreirosbeing invaded and destroyed. The religious are being persecuted. Marina hasn’t no positioned herself (on this) and has support of some of the main enemies of these religions.”

Speaking to BBC Brasil, Valneide Nascimento, national political coordinator of and racial equality promotion of the campaign, recognizes the flaws.

“Not detailing (the policy on religions) was our mistake,” she said by telephone.

Note from BW of Brazil: With black Brazilians being nearly invisible in Brazil’s sphere’s of power, one would think that the strong possibility of Marina Silva becoming the first black president in the nation’s history would have more feelings of hope and celebration within the Afro-Brazilian community. Well, this is not exactly how is looking for Silva. According to recent numbers, the incumbent president, Dilma Rouseff leads with 37% of the intended vote, while Marina carries 31% and Aécio Neves, 15%. But those same reports last week were predicting that once Aécio Neves dropped out of the race and Silva goes head to head with Rouseff, Silva would claim a victory. A report by Financial Times out today reveals that Silva and Rouseff would be in a tie without Neves in the race.

Breaking last week’s number down even further, we find that Dilma is the favorite among Catholics (40% to 31%), while Silva claims an edge (43% to 32%) with Evangelicals and a slight edge (32% to 30%) among persons of other religions. In terms of economic class, Dilma leads among Brazil’s poorest (49% to 27% among those earning one minimum salary per month and 38% to 33% among those who earn two minimum salaries), Marina leads among those who earn more than five minimum salaries (37% to 28%) while there is 35% tie between the two women in terms of people who earn between two and five minimum salaries per month.

Current President, Dilma Rouseff and candidate Marina Silva

We also see a sort of rich/poor break down in terms of support by education. For those who have up to a 4th grade education and between 5th and 8th grade, Dilma leads (50% to 25% and 44% to 29%, respectively) while Marina has the support of those who graduated from high school (38% to 33%) and those who graduated from college (37% to 24%). In terms of the racial question, numbers from late August and early September suggest that 40% of the Afro-Brazilian population intends to vote for Dilma versus 28% who intend to vote for Marina. These same reports show that the third candidate, Aécio Neves, would receive about 12% of the black vote, which is exactly the difference between Rouseff and Silva among this segment of the population. This could be a huge factor for either of the eventual two candidates, which will certainly be Silva and Rouseff.

According to research from TSE, PNAD/IBGE, the população negra (black population or the sum of pretos/blacks and pardos/browns) makes up 55% of qualified voters for the 2014 election, the first that this parcel of the population represents the majority. And as the black population represents the larger percentage of poor Brazilians, we can also see how, for the most part, race and class are also intimately linked in the upcoming election. In the past 12 years, under PT (Partido dos Trabalhadores or Workers Party) presidents Lula da Silva and Rouseff, the poor and black population made great gains in terms of access to higher education and ascension into the middle classes, which could explain why the black and poor seem to be remaining faithful to the possibility of Dilma’s re-election. This is part of the reason that this election cannot be simply seen as a racial vote with the population that looks more like Marina Silva voting for her based on identity politics. And there are a number of reasons for this.

Marina Silva lags behind incumbent President Dilma Rouseff in terms of black support

1) Even though racism, racial exclusion and white supremacy continue to reign supreme in Brazil, non-white people see this election, as always, as a chance to support the candidate that will most likely create policies in their interests. And with reputation of the PT connected to the struggle of “the people” (even with its rightward turn in recent years) and 12 years of economic improvement for this population, Dilma remains the favorite. 2) Racial numbers in Brazil can never been seen as absolute and cannot automatically be assumed that persons see themselves as others may seen them. What does it say for identity politics if we take note of a female who physically looks likes Marina Silva but sees defines herself as branca (white)? As there are millions of people in Brazil who would fit this phenotype, it would throw off the entire prediction.

3) In a clear difference in comparison with US President Barack Obama’s carrying of 95% of the African-American vote in the 2008 election, the dream of actually seeing a black president isn’t as strong a sentiment that could overcome other factors associated with quality of life and social ascension in Brazil. How else can one explain the fact that during his historic run for the presidency in 2008, Obama actually said very little about what he would do to improve the plight of black Americans and yet African-Americans overwhelmingly voted for him anyway. Sure, one would expect that in a country like Brazil in which the power structure is overwhelmingly white that non-whites would vote for someone who looked like them, but also remember that racial identity in Brazil is not as black and white as it is in the US. 4) There is an old saying in Brazil that even blacks don’t for blacks, thus, it is very likely that there are persons of visible African ancestry who would never vote for Marina regardless of how much she spoke to their interests.

5) Although Marina has identified herself as a black woman, her campaign as not as of yet spoken directly to concerns of black Brazilians, or better, persons of visible African descent. There are several key issues to consider in this issue. First, if she were to speak directly to the “black community” how many people would that actually be, as the vast majority of persons of visible African ancestry don’t actually define themselves asnegro/negra/black. Second, it is apparent that Marina, as any other candidate, must represent the wishes of the big money interests that are backing her. This clearly doesn’t apply to non-whites as they don’t represent big money, business interest nor political power. Although white supremacy is clearly visible in Brazil, because of a different history with less open racial conflict (despite the strong presence of racism/white supremacy), aspirations simply aren’t as tied directly to race in Brazil as they are in US. In fact, rather than seeing Marina as a female Obama, one could argue that in this election, President Rouseff may represent a figure closer to someone like a US President Lyndon Johnson in the minds of non-white Brazilians: a white political figure who is deemed to be in solidarity with an excluded parcel of the population is search of social ascension. And judging from the plight of African-Americans under nearly six years of the first black president, maybe it would be a good idea for Afro-Brazilians to analyze these candidates beyond the perspective of race.

The only black presidential candidate, Marina suffers resistance amongafrodescendentes (African descendants)

Activists and researchers of the black movement say that Marina has no ties to militancy

Marina is viewed with “suspicion” by blacks, academics, social organizations and activists. The more backward evangelical leaders of Brazil, like Malafaia and Feliciano, support her with force

by Ricardo Senra

“Brazilian nata, born in Rio Branco, Acre, on February 8, 1958, female, color/race preta(black) (1),” says the document from the Superior Electoral Court that formalizes Marina Silva’s candidacy for president.

In 2010, when she ran for the Planalto (quarters of Brazilian president) (2) for the first time, Marina said she wanted to be “the first black woman, from a poor background, President of the Federative Republic of Brazil.” Four years later, it appears, according to IBOPE, in the leader among intentions of white voters, but behind Dilma Rousseff among blacks and mulatos.

Despite being the only one of the three leading candidates to devote an entire chapter of her government program for the black population, the former senator is not perceived as a representative of that portion of the electorate.

Evangelical, daughter of mestiça (mixed race) mother and black father, Marina is analyzed with suspicion by academics, research institutes, social organizations and activists interviewed by BBC Brasil.

The most frequent criticisms question the candidate’s stance on issues important to black militancy. Freedom for religions of African origin, the land registry for quilombocommunities, viability of affirmative policies such as racial quotas, and the lack of links with the movement were the main points raised by respondents.

Paulino Cardoso, president of the Associação Brasileira de Pesquisadores Negros

“We are very happy that someone self-declares themselves black, but under no circumstances does Marina represent the struggle of this population,” says Professor Paulino Cardoso, president of the Associação Brasileira de Pesquisadores Negros (ABPN or Brazilian Association of Black Researchers) and researcher of Afro-Brazilian culture for 30 years.

“We [blacks] are the poorest of the poor in Brazil,” said Cardoso. “Will it be that the State streamlines what she promises, of neoliberal character, with an independent Banco Central (Central Bank) will able to fund our social policies? Blacks rely heavily on these initiatives, they cost more than R$12 billion (US$5.16 billion) for the government and are frowned upon by oligarchies,” says the professor.

Marina’s committee assured that the candidate would personally respond to questions sent by BBC on the subject by BBC Brasil. After cancelling the commitment twice, aides failed to respond to the report.

Allies

A PhD in psychology, Elisa Nascimento, president of Ipeafro (Instituto de Pesquisas e Estudos Afro Brasileiros or Research Institute of Afro Brazilian Studies), says that political allies of Marina can compromise her stance on religious tolerance.

To the press, Silva repeatedly said that she defends a “secular state”. The candidate, however, has the support of important Evangelical political leaders – such as the congressman Marco Feliciano (PSC-SP), who has said “to prophesy the burial of the pais de santo (Afro-Brazilian religion priests)” and the “closure of the terreiros de macumba.” (3)

“I have seen Marina try to unbind religion from her positions, but it is evident that her beliefs influence her political action. There are Neo-pentecostals who repeatedly disrespect the Candomblé and Umbanda (Afro-Brazilian religions). There are terreirosbeing invaded and destroyed. The religious are being persecuted. Marina hasn’t no positioned herself (on this) and has support of some of the main enemies of these religions.”

Speaking to BBC Brasil, Valneide Nascimento, national political coordinator of and racial equality promotion of the campaign, recognizes the flaws.

“Not detailing (the policy on religions) was our mistake,” she said by telephone.

Marina Silva, left, with Valneide Nascimento

“Like Marina, I, the national coordinator, am also Protestant and we didn’t have an accumulation of knowledge about religions of African origin,” she says. “We didn’t put it in because we didn’t have an understanding on how it should be, at the time.”

Valneide, however, denies other alterations in the government program – in late August, the PSB eliminated sections of the chapter directed at LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and transsexuals) rights. The change was justified at the time as “a failure in the publishing process.”

“We will not change. Religions are in the program, what was missing was the detailing. But we will announce these details in person on the 20th, in Salvador.”

Quilombolas

According to the 2013 Fundação Cultural Palmares (Palmares Cultural Foundation), at least 1,281 quilombola communities are in the formalization process, with only 21 having their territories effectively titled as recommended by the Constitution.

The government program announced by Rousseff does not cite quilombolas at any moment.

Presidential candidates and the black population

Candidates for the presidency: Current President Dilma Rouseff, Aécio Neves and Marina Silva

Policies directed at the black population proposed in the government plans of Aécio Neves and Dilma Rousseff, Silva’s chief competitors in the race for the Planalto, are much leaner than the PSB candidate.

In her program, consisting of 242 pages, Marina is the only one to devote a whole chapter to afrodescedentes (African descendants) and other traditional communities, including quilombolas.

Aécio, whose full program has 76 pages, proposes, on topics, joint initiatives for “blacks, women, elderly, children, LGBT, quilombolas, ciganos (gypsies), indigenous peoples and disabled people”, without distinction between policies for each groups.

Dilma’s government program (42 pages) says defending the “fight against discrimination and the promotion of racial equality” as “priority tasks”, assuming the “challenge of making a reality of the Quota Law in the federal public service, culminating in June 2014, guaranteeing the same efficiency already achieved by the law of quotas in public universities.”

The current president’s program also highlights “addressing violence against young blacks” by expanding the Programa Juventude Viva (youth program).

Aécio Neves mentions the “implementation of support and assistance programs for quilombola communities”, besides references to “vulnerable sectors” such as “women, children, elderly, afrodescendentes, LGBT, quilombolas, gypsies, persons with disabilities, victims of violence and indigenous peoples”.

In addition to citing quilombolas 34 times, Marina’s program is the only one to dedicate a chapter to the subject.

In the text, she promises to “accelerate the processes of recognition and titling of quilombo lands”, “improve the water supply, sewer and garbage collection”, “curb property speculation in and around areas of quilombos”, among other initiatives. Even so, her proposals meet resistance.

João Jorge Rodrigues of Olodum sees a conflict in Silva’s candidacy

“Culturally, the boundaries of the negotiation of lands for traditional communities come up against agriculture. Demarcation will never be the interest of the owners,” says João Jorge Rodrigues, owner of a master’s in Public Law and president of the organization Olodum, in Bahia.

“How can announce a series of policies for quilombolacommunities while having an agribusiness leader as her vice?” he asks.

Paulino Cardoso, of ABPN is also skeptical. “Marina allies herself with banks and oligarchs to do what is called new politics. On paper she accepts everything. We need to know how it will be done.”

Quotas for ten years

The three main presidential candidates in this election defend the policy of racial quotas in universities.

“Marina Silva and no other candidate for the presidency position themselves (on policies for blacks). The political class is still far behind in this.”

In her government program, the ex-senator says “reaffirming the importance of quotas for black people, as a temporary, emergency and reparatory of the historical debt with an expected date to end.”

Dilma Rousseff says she plans to “make the Quota Law a reality in the federal public service, guaranteeing the same effectiveness already achieved in the quota law in the universities.” Aécio Neves follows the same line, preaching the “defense and maintenance of affirmative action for social inclusion, including quotas, because of race.”

Widow of former Senator Abdias do Nascimento, creator of the Teatro Experimental do Negro (Black Experimental Theater) in 1940 and awarded by UNESCO for his pioneering in the fight for the rights of the black population, Elisa Nascimento, president of Ipeafro criticizes the text of the PSB candidate’s program on quotas.

“She talks about quotas as a measure with an expected date to end, but I don’t see how to determine a date. We are far from a social situation of equilibrium without statistical inequalities between blacks and whites,” she says.

According to the IBGE, 66.6% of white students between 18-24 years of age attend college, while 37.4% of pretos (blacks) and pardos (browns) are in higher education.

Speaking to BBC Brasil, the coordinator of Marina’s racial program says that within 10 years the transition from racial quotas to social quotas would be expected.

“We don’t want blacks to stay forever dependent on quotas,” says Valneide Nascimento.

“The racial dimension of the quotas is necessary because poverty and racism are different things,” counter argues Elisa. “The racial factor is another and is not resolved with general policies.”

Symbol

For Jurema Werneck, none of the candidates have positioned themselves on the issue of Afro-Brazilians

For the doctor Jurema Werneck, of theArticulação de Organizações de Mulheres Negras (Articulation of Black Women’s Organizations), the lack of effective proposals for the black population is a problem common to all candidates.

The possibility of a black president “is symbolically important,” says the activist.

“But this is a symbolism that speaks of the past, of the struggle waged by the Movimento Negro (black movement) and that allowed her to get there,” he says. “Marina Silva and no other candidate for the presidency have positioned themselves [on policies for blacks]. The political class is still far behind in this.”

For Thais Santos, of the Coletivo Negro (Black Collective), of the University of São Paulo (USP), the candidate declaring or not declaring herself black “does not mean much.”

João Jorge Rodrigues, president of Olodum, says quilombola policies are incompatible with agribusiness

“In a country where many blacks don’t understand themselves as blacks, they will not understand her also. If she declares this in advertisements, if that was part of her campaign, this would be something else.”

The biography of the candidate, published on her official campaign website does not mention her color. Even so, Dennis de Oliveira, USP professor and coordinator of the collective Quilombação, considers it important that Afro-Brazilians earn space in spheres of power – and cites Joaquim Barbosa, former president of the Federal Supreme Court.

“Marina campaigned with rubber tappers, but I don’t recall policies for the black population,” he says. “She is much more perceived on the environmental issue than for her identification with blacks.”

According to the coordinator of racial policies, Valneide Nascimento, “the program was constructed with the participation of representatives of society and militancy in Brazil.”

Asked which groups of militancy in which they participated, Nascimento didn’t know how to respond. “There were many, we called and they came.”

Notes

1. This fact is quite surprising. In Brazil, it is difficult to find persons of Silva’s skin color classified as preta/preto, meaning black, on their birth certificates. Even those who most would classify as black and possessing medium to dark brown skin are often defined as pardo/parda (brown) on their birth certificates. Historically, Brazil has always tried to hide/erase its black population, and still today, persons of African ancestry are encouraged to define themselves in lighter-skinned categories (see here,here or here)

2. The Palácio do Planalto is the official workplace of the President of Brazil. It is located in the national capital of Brasília.

3. A terreiro is a temple of worship for followers of Afro-Brazilian religions. The term “macumbeira” is a derogatory term used in reference to persons who are thought to practice “macumba”, which was the name used for all Bantu religious practices mainly by Afro-Brazilians in the northeastern state of Bahia in the 19th Century. “Macumba”, and the term “Macumbeira”, became common in some parts of Brazil and this word is used by most people as a pejorative word meaning “black witchcraft”, although actual practitioners don’t view the term negatively. In some ways, it is equal to saying someone practices “Voodoo” or “Voudoon”, another misunderstood, negatively viewed religion practiced in Haiti. “Macumbeira” is a common used term to slight Afro-Brazilians whether they are actually practitioners of Afro-Brazilian religions or not.

DreadBrown

Feed the children

JAMAICA

Bogdanovich takes largest stake in KLE

Music promoter to leverage contacts, wealth to grow entertainment company’s brand

Wednesday, September 17, 2014

(L-R) Gary Matalon and Josef Bogdanovich

MUSIC promoter Josef Bogdanovich now owns the largest shareholdings in the Kingston Live Entertainment (KLE) Group.

It's part of an overall strategy to allow Bogdanovich to leverage his contacts and wealth to grow the brand.

"It should help us to achieve our vison sooner," said Gary Matalon, the former largest shareholder of KLE, which aims to be an international entertainment group.

"He has about 23 per cent of the shareholding and I have 16 per cent," said Matalon, the CEO of the KLE Group, in an interview with the Jamaica Observer at the Tracks & Records in Kingston yesterday.

In July, Bogdanovich acquired 7.1 million shares from director Craig Powell, then in September acquired 8.1 million shares from director Kevin Bourke and 5.9 million shares from director Zuar Ard Jarrett , said Matalon. All directors still hold some shares following the sale.

"Based on his contacts and experience over the years, it's an honour to work with someone like that," he said. Part of that contact list involves the group possibly hosting one of the world's most known sportsmen, later this year.

"We can't even pay for his jet fuel," he said of the unnamed sportsman. "But Joe's contacts are incredible."

Bogdanovich aims to capitalise on the company's growth prospects based on Usain Bolt's Tracks & Records' franchise opportunities in New York, USA and Montego Bay, Jamaica.

Bogdanovich is a co-partner in the staging of the annual show, Sting.

He also operates Downsound Records — a popular studio that produces Ninjaman, Specialist and other deejays. He also traded commodities and is said to be part heir to a sizeable stake in the Heinz empire. Downsound Records indicated that Bogdanovich declined to comment up to press.

The sale of shares represents the largest block transactions since listing on the Junior Market in 2012.

"His initial interest was on Famous nightclub then he became interested in the overall KLE Group because of our intention to franchise the Tracks & Records brand. Then he said that he wanted to be involved in everything," Matalon explained. "In order for us to execute our [partnership] he wanted to ensure that he has a meaningful stake."

Matalon still holds 13.6 million KLE shares, the second largest of the 100 million outstanding. Also, the shares controlled by sprinter Usain Bolt via Sherwood Holdings remain unchanged at 6.7 million units.

KLE's stock price lost ground over 52 weeks from $1.61 to $1 up to Monday.

The stock suffered from quarterly losses but also from an otherwise depressed stock market.

"Expect announcements in the coming weeks," Matalon said on new revenue measures.

KLE operates Fiction, Famous Night Club and Usain Bolt's Tracks & Records. It recorded a $12.6-million loss for the March quarter compared with a $17.2-million loss a year earlier. In addition to restructuring, the business has focused on its franchising model for Tracks & Records.

Matalon responded when asked why Bogdanovich would invest in a loss-making venture: "The KLE potential is huge. I do not know many other companies that can export and earn foreign exchange today [as a franchise] and for the past three years we have been develiping the franchise model".

KLE now operates Fiction night club in a joint venture partnership through which KLE owns a 40 per cent stake, Matalon indicated.

KLE Group, in its initial public offering, raised $94 million.

http://www.jamaicaobserver.com/business/Bogdanovich-takes-largest-stake-in-KLE_17556513

Bogdanovich takes largest stake in KLE

Music promoter to leverage contacts, wealth to grow entertainment company’s brand

Wednesday, September 17, 2014

(L-R) Gary Matalon and Josef Bogdanovich

MUSIC promoter Josef Bogdanovich now owns the largest shareholdings in the Kingston Live Entertainment (KLE) Group.

It's part of an overall strategy to allow Bogdanovich to leverage his contacts and wealth to grow the brand.

"It should help us to achieve our vison sooner," said Gary Matalon, the former largest shareholder of KLE, which aims to be an international entertainment group.

"He has about 23 per cent of the shareholding and I have 16 per cent," said Matalon, the CEO of the KLE Group, in an interview with the Jamaica Observer at the Tracks & Records in Kingston yesterday.

In July, Bogdanovich acquired 7.1 million shares from director Craig Powell, then in September acquired 8.1 million shares from director Kevin Bourke and 5.9 million shares from director Zuar Ard Jarrett , said Matalon. All directors still hold some shares following the sale.

"Based on his contacts and experience over the years, it's an honour to work with someone like that," he said. Part of that contact list involves the group possibly hosting one of the world's most known sportsmen, later this year.

"We can't even pay for his jet fuel," he said of the unnamed sportsman. "But Joe's contacts are incredible."

Bogdanovich aims to capitalise on the company's growth prospects based on Usain Bolt's Tracks & Records' franchise opportunities in New York, USA and Montego Bay, Jamaica.

Bogdanovich is a co-partner in the staging of the annual show, Sting.

He also operates Downsound Records — a popular studio that produces Ninjaman, Specialist and other deejays. He also traded commodities and is said to be part heir to a sizeable stake in the Heinz empire. Downsound Records indicated that Bogdanovich declined to comment up to press.

The sale of shares represents the largest block transactions since listing on the Junior Market in 2012.

"His initial interest was on Famous nightclub then he became interested in the overall KLE Group because of our intention to franchise the Tracks & Records brand. Then he said that he wanted to be involved in everything," Matalon explained. "In order for us to execute our [partnership] he wanted to ensure that he has a meaningful stake."

Matalon still holds 13.6 million KLE shares, the second largest of the 100 million outstanding. Also, the shares controlled by sprinter Usain Bolt via Sherwood Holdings remain unchanged at 6.7 million units.

KLE's stock price lost ground over 52 weeks from $1.61 to $1 up to Monday.

The stock suffered from quarterly losses but also from an otherwise depressed stock market.

"Expect announcements in the coming weeks," Matalon said on new revenue measures.

KLE operates Fiction, Famous Night Club and Usain Bolt's Tracks & Records. It recorded a $12.6-million loss for the March quarter compared with a $17.2-million loss a year earlier. In addition to restructuring, the business has focused on its franchising model for Tracks & Records.

Matalon responded when asked why Bogdanovich would invest in a loss-making venture: "The KLE potential is huge. I do not know many other companies that can export and earn foreign exchange today [as a franchise] and for the past three years we have been develiping the franchise model".

KLE now operates Fiction night club in a joint venture partnership through which KLE owns a 40 per cent stake, Matalon indicated.

KLE Group, in its initial public offering, raised $94 million.

http://www.jamaicaobserver.com/business/Bogdanovich-takes-largest-stake-in-KLE_17556513

DreadBrown

Feed the children

JAMAICA

GK (Grace Kennedy) Capital eyes big stake in venture capital funds

Wednesday, September 17, 2014

WEHBY... we are looking at small and medium local companies that we can help to grow, especially in the overseas market…

GK Capital Management plans to invest big in the venture capital market in Jamaica.

The investment company might even take a few of the companies that it invests in to market “whether through the stock exchange or through the junior stock exchange”, according to GraceKennedy Group CEO, Don Wehby.

Previously, GK Capital signalled that it would be willing to invest up to US$2 million in venture funds which have a total value of US$20 million or upwards.

That is, if 70 per cent or more of the funds are invested in Jamaican companies, according to the Development Bank of Jamaica (DBJ) in its 'Call for Proposals from Local and International Venture Captial and Private Equity Funds' dated July 31.

“I have been waiting on the day for us to put in place the proper infrastructure for venture capital and I am hoping that it will not take too long before we can start rolling out,” said Webhy. Though the conglomerate has placed priority on investing in food manufacturing and agro-food processing companies, GraceKennedy’s investment company is placing no restrictions on the type of businesses that it invests in.

The CEO said that GK Capital will be keeping an eye open for investment opportunities that do not fall squarely within its core business. The information technology (IT) and animation sectors are two such areas that GraceKennedy has expressed strong interest in.

The rate at which these areas have been growing makes them ripe for investment, Wehby reckons. At this stage, “we are looking at small and medium local companies that we can help to grow, especially in the overseas market… as this falls within GraceKennedy's export led growth strategy,” said the Group CEO. GK Capital is also not ruling out the possibility of investing in some start-up companies as well.

Webhy said that, as long as the due diligence and market research points to the company growing significantly as a result of Gracekennedy's investment of capital, human resources and management discipline, they are willing to invest.

GK Capital Management is one of the eleven companies that are seeking to take equity positions in the formation of venture capital funds that is being facilitated by the DBJ, through which they will evaluate projects and deals in which they will consider investing. The DBJ aims to have the first venture capital fund up and running by next year.

GK (Grace Kennedy) Capital eyes big stake in venture capital funds

Wednesday, September 17, 2014

WEHBY... we are looking at small and medium local companies that we can help to grow, especially in the overseas market…

GK Capital Management plans to invest big in the venture capital market in Jamaica.

The investment company might even take a few of the companies that it invests in to market “whether through the stock exchange or through the junior stock exchange”, according to GraceKennedy Group CEO, Don Wehby.

Previously, GK Capital signalled that it would be willing to invest up to US$2 million in venture funds which have a total value of US$20 million or upwards.

That is, if 70 per cent or more of the funds are invested in Jamaican companies, according to the Development Bank of Jamaica (DBJ) in its 'Call for Proposals from Local and International Venture Captial and Private Equity Funds' dated July 31.

“I have been waiting on the day for us to put in place the proper infrastructure for venture capital and I am hoping that it will not take too long before we can start rolling out,” said Webhy. Though the conglomerate has placed priority on investing in food manufacturing and agro-food processing companies, GraceKennedy’s investment company is placing no restrictions on the type of businesses that it invests in.

The CEO said that GK Capital will be keeping an eye open for investment opportunities that do not fall squarely within its core business. The information technology (IT) and animation sectors are two such areas that GraceKennedy has expressed strong interest in.

The rate at which these areas have been growing makes them ripe for investment, Wehby reckons. At this stage, “we are looking at small and medium local companies that we can help to grow, especially in the overseas market… as this falls within GraceKennedy's export led growth strategy,” said the Group CEO. GK Capital is also not ruling out the possibility of investing in some start-up companies as well.

Webhy said that, as long as the due diligence and market research points to the company growing significantly as a result of Gracekennedy's investment of capital, human resources and management discipline, they are willing to invest.

GK Capital Management is one of the eleven companies that are seeking to take equity positions in the formation of venture capital funds that is being facilitated by the DBJ, through which they will evaluate projects and deals in which they will consider investing. The DBJ aims to have the first venture capital fund up and running by next year.

DreadBrown

Feed the children

JAMAICA

Change Ja In Order To Tackle HIV/AIDS

Published: Wednesday | September 17, 20140 Comments

- Harvey

DR KEVIN Harvey, acting permanent secretary in the Ministry of Health, said for a country to be free of persons living with human immunodeficiency virus and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS), policymakers must have the courage to do things differently.

Speaking at the Pan American Health Organisation (PAHO) Treatment 2.0 Conference on Monday, Harvey said it cannot be business as usual.

"We have had demonstration projects within our own country, which shows that we can't continue to do business the same way if we are to end the HIV/AIDS epidemic. If we don't refocus the programme on what the evidence shows, then we will be battling this for the next 20 years," he declared.

"Jamaica is at a critical stage in the HIV/AIDS response and, as the evidence emerges, as it relates to Jamaica's response, we have demonstrated the ability to adapt and to have the greatest impact, but we have to take it a step further," he said, while addressing the audience at PAHO offices at the University of the West Indies, Mona.

Harvey called for more to be done to end discrimination against vulnerable groups in society.

"We will have to implement mechanisms that mitigate against stigma and discrimination, particularly where we provide treatment and care, and also to facilitate access to the vulnerable population to ensure that they can be reached," he said.

"We have seen where conversations have increased when it comes to vulnerable groups which is good, but we would appreciate if this conversation continues along with heightened action mechanisms," Harvey said.

Similarly, Denise Herbol, mission director for United States Agency for International Development, said there must be strategic approaches to curbing incidents of the illness.

"There is now ways to achieve an AIDS-free future without targeted approaches to our key populations, which would include men who have sex with men, their partners, commercial sex workers and their clients. These people often face inadequate access to services as persistent societal barriers stand in their way," she said.

"The implementation and scale-up of comprehensive prevention and treatment interventions are critical in order to address the burden of HIV that these marginalised groups face. We must also reduce the stigma and discrimination faced by these populations and expand access to services for these groups," she declared.

jodi-ann.gilpin@gleanerjm.com

Change Ja In Order To Tackle HIV/AIDS

Published: Wednesday | September 17, 20140 Comments

- Harvey

DR KEVIN Harvey, acting permanent secretary in the Ministry of Health, said for a country to be free of persons living with human immunodeficiency virus and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS), policymakers must have the courage to do things differently.

Speaking at the Pan American Health Organisation (PAHO) Treatment 2.0 Conference on Monday, Harvey said it cannot be business as usual.

"We have had demonstration projects within our own country, which shows that we can't continue to do business the same way if we are to end the HIV/AIDS epidemic. If we don't refocus the programme on what the evidence shows, then we will be battling this for the next 20 years," he declared.

"Jamaica is at a critical stage in the HIV/AIDS response and, as the evidence emerges, as it relates to Jamaica's response, we have demonstrated the ability to adapt and to have the greatest impact, but we have to take it a step further," he said, while addressing the audience at PAHO offices at the University of the West Indies, Mona.

Harvey called for more to be done to end discrimination against vulnerable groups in society.

"We will have to implement mechanisms that mitigate against stigma and discrimination, particularly where we provide treatment and care, and also to facilitate access to the vulnerable population to ensure that they can be reached," he said.

"We have seen where conversations have increased when it comes to vulnerable groups which is good, but we would appreciate if this conversation continues along with heightened action mechanisms," Harvey said.

Similarly, Denise Herbol, mission director for United States Agency for International Development, said there must be strategic approaches to curbing incidents of the illness.

"There is now ways to achieve an AIDS-free future without targeted approaches to our key populations, which would include men who have sex with men, their partners, commercial sex workers and their clients. These people often face inadequate access to services as persistent societal barriers stand in their way," she said.

"The implementation and scale-up of comprehensive prevention and treatment interventions are critical in order to address the burden of HIV that these marginalised groups face. We must also reduce the stigma and discrimination faced by these populations and expand access to services for these groups," she declared.

jodi-ann.gilpin@gleanerjm.com

Trinidad and Tobago to Hold Investment Conference in New York City

September 15, 2014 | 4:23 pm |Print

Above: Trinidad (CJ Photo)

By the Caribbean Journal staff

Trinidad and Tobago is ramping up its push to attract foreign investment.

The country’s government announced this week that it would be holding an investment conference in New York later this month.

The conference, which will take place on Sept. 25, will be held at the Council on Foreign Relations on E 68th Street.

The event will focus on the country’s “competitive advantages as a business location” and its “advancements in economic diversification, foreign investment, foreign policy, energy, competitiveness and innovation,”according to a release.

Trinidad and Tobago Prime Minister Kamla Persad-Bissessar will be attending the conference, joined by Trade Minister Vasant Bharath, Planning and Sustainable Development Minister Bohendradatt Tewarie and Energy Minister Kevin Ramnarine, among others.

September 15, 2014 | 4:23 pm |Print

Above: Trinidad (CJ Photo)

By the Caribbean Journal staff

Trinidad and Tobago is ramping up its push to attract foreign investment.

The country’s government announced this week that it would be holding an investment conference in New York later this month.

The conference, which will take place on Sept. 25, will be held at the Council on Foreign Relations on E 68th Street.

The event will focus on the country’s “competitive advantages as a business location” and its “advancements in economic diversification, foreign investment, foreign policy, energy, competitiveness and innovation,”according to a release.

Trinidad and Tobago Prime Minister Kamla Persad-Bissessar will be attending the conference, joined by Trade Minister Vasant Bharath, Planning and Sustainable Development Minister Bohendradatt Tewarie and Energy Minister Kevin Ramnarine, among others.

Mr Bubbles

Superstar

Here are some videos on the Jamaican Stock Exchange (JSE)

If I could dap this post more than once I would. A cartoon commercial with only black people? I could cry.

DreadBrown

Feed the children

JAMAICA

Saturday at Linstead Market

Thursday, September 18, 2014

A bustling market day. (PHOTOS: LIONEL ROOKWOOD)

Immortalised in the popular Jamaican folk song, Linstead Market is home to a colourful cast of vendor personalities, with stalls stocked with a distinct array of farm-fresh produce and veggies as Thursday Life went a-calling last weekend. Get your shopping list ready as we venture to the iconic St Catherine space to see a Saturday market day in action.

The Linstead Market of today is markededly different from the one of the past. While not aesthetic perfection, in the 40-plus years that octogenarian Juletta Stuart has been a vendor in the St Catherine township, the market has been transformed from an open lot to a sheltered, one-storey building (albeit, with a roof that currently needs urgent replacement) where vendors are required to pay a daily fee to sell their produce. “It wasn’t like this,” a fedora-wearing Stuart tells us. With small stacks of coconuts, June plums, nutmegs and plantains lying on a crocus bag-lined display before her, Stuart, sitting on a stool and initially a tad hesitant to engage our enquiries, volunteers: “We used to be on an open compound before this was built.”

While happy with the transformation, the elderly vendor is, however, unhappy with the economic shift that the passage of time has dealt to her earnings.

“Everything gone down flat,” she bemoans. “Sales bad now; first time you could get money and hold onto it, but now the money not really there, and it goes so fast.”

The complaint of slower-paced sales is not singularly hers. It’s oft-repeated by other vendors with whom we interface as we troll around the market.

The violet-haired Herma Hunt feels a turn in the tide. “Sometimes business is bad, sometimes good,” she notes. A veteran vendor in the Linstead Market, Hunt started selling there at 18. “When I was going to high school, I had to come and sell to help make up my lunch money,” she recalls.

Counting Saturday as one of the market’s better sale days, Hunt tells us that the recent drought has created a scarcity for some goods, and caused price hikes for a number of items including tomatoes (which presently surpass $200 for a dozen) and lettuce (now $400 a head).

Fluctuating earnings notwithstanding, the stocky and spirited vendor, much like her peers, has a fondness for her job. “I love what I do because it makes me independent,” enthuses Hunt.

Melvill Drummond — whose stall of yams, bananas, carrots, sweet potatoes and corn is mere steps away from Hunt’s — is thankful and always eager to show up to sell in the market, which he has done for the last 12 years.

“It helps me to send my kids to school and take care of my family,” the good-natured and chatty Drummond divulges. A Clarendon-based farmer, he says his day in the market typically begins at 5:00 am, but could be later, depending on his ability to access a route taxi to transport him. The workday for him ends when he has parted with most of his stock. “Me not going home until me sell off,” he shares.

We soon make acquaintance with Latoya Lee, yet another chirpy vendor. Lee made the transition from selling clothes to produce and veggies five years ago. “I used to sell clothes, then I thought maybe I should do food because food is a must,” she explains. With clothing vendors populating the market in equal numbers as food vendors, Lee is grateful for having pulled a switcheroo, seeing better sales. “It’s up and it’s down,” Lee notes. “But I really like it.”

— Omar Tomlinson

Latoya Lee shells ackee from the pods. “I like when I make a spread of my food items and people say, ‘I like how your things look good just like you’.” Like most all vendors in Linstead Market, the majority of vegetables, fruits and ground provisions are bought at Coronation Market in Kingston.

Vendor Lurline Halladene (right) entertains questions from customer Ethel Henry.

Vendor Marlette Bertram bags lemons. (AT RIGHT) Terril Nembhard, who has worked as a vendor for 10 years at the Linstead Market alongside his grandmother, bags sorrel (sale price: $150 per pound) last Saturday. “I am able to send my children to school; they have food to eat and I’m not a trouble to anyone as I’m self-dependent,” Nembhard says.

http://www.jamaicaobserver.com/Saturday-at-Linstead-Market_17548474

Saturday at Linstead Market

Thursday, September 18, 2014

A bustling market day. (PHOTOS: LIONEL ROOKWOOD)

Immortalised in the popular Jamaican folk song, Linstead Market is home to a colourful cast of vendor personalities, with stalls stocked with a distinct array of farm-fresh produce and veggies as Thursday Life went a-calling last weekend. Get your shopping list ready as we venture to the iconic St Catherine space to see a Saturday market day in action.

The Linstead Market of today is markededly different from the one of the past. While not aesthetic perfection, in the 40-plus years that octogenarian Juletta Stuart has been a vendor in the St Catherine township, the market has been transformed from an open lot to a sheltered, one-storey building (albeit, with a roof that currently needs urgent replacement) where vendors are required to pay a daily fee to sell their produce. “It wasn’t like this,” a fedora-wearing Stuart tells us. With small stacks of coconuts, June plums, nutmegs and plantains lying on a crocus bag-lined display before her, Stuart, sitting on a stool and initially a tad hesitant to engage our enquiries, volunteers: “We used to be on an open compound before this was built.”

While happy with the transformation, the elderly vendor is, however, unhappy with the economic shift that the passage of time has dealt to her earnings.

“Everything gone down flat,” she bemoans. “Sales bad now; first time you could get money and hold onto it, but now the money not really there, and it goes so fast.”

The complaint of slower-paced sales is not singularly hers. It’s oft-repeated by other vendors with whom we interface as we troll around the market.

The violet-haired Herma Hunt feels a turn in the tide. “Sometimes business is bad, sometimes good,” she notes. A veteran vendor in the Linstead Market, Hunt started selling there at 18. “When I was going to high school, I had to come and sell to help make up my lunch money,” she recalls.

Counting Saturday as one of the market’s better sale days, Hunt tells us that the recent drought has created a scarcity for some goods, and caused price hikes for a number of items including tomatoes (which presently surpass $200 for a dozen) and lettuce (now $400 a head).

Fluctuating earnings notwithstanding, the stocky and spirited vendor, much like her peers, has a fondness for her job. “I love what I do because it makes me independent,” enthuses Hunt.

Melvill Drummond — whose stall of yams, bananas, carrots, sweet potatoes and corn is mere steps away from Hunt’s — is thankful and always eager to show up to sell in the market, which he has done for the last 12 years.

“It helps me to send my kids to school and take care of my family,” the good-natured and chatty Drummond divulges. A Clarendon-based farmer, he says his day in the market typically begins at 5:00 am, but could be later, depending on his ability to access a route taxi to transport him. The workday for him ends when he has parted with most of his stock. “Me not going home until me sell off,” he shares.

We soon make acquaintance with Latoya Lee, yet another chirpy vendor. Lee made the transition from selling clothes to produce and veggies five years ago. “I used to sell clothes, then I thought maybe I should do food because food is a must,” she explains. With clothing vendors populating the market in equal numbers as food vendors, Lee is grateful for having pulled a switcheroo, seeing better sales. “It’s up and it’s down,” Lee notes. “But I really like it.”

— Omar Tomlinson

Latoya Lee shells ackee from the pods. “I like when I make a spread of my food items and people say, ‘I like how your things look good just like you’.” Like most all vendors in Linstead Market, the majority of vegetables, fruits and ground provisions are bought at Coronation Market in Kingston.

Vendor Lurline Halladene (right) entertains questions from customer Ethel Henry.

Vendor Marlette Bertram bags lemons. (AT RIGHT) Terril Nembhard, who has worked as a vendor for 10 years at the Linstead Market alongside his grandmother, bags sorrel (sale price: $150 per pound) last Saturday. “I am able to send my children to school; they have food to eat and I’m not a trouble to anyone as I’m self-dependent,” Nembhard says.

http://www.jamaicaobserver.com/Saturday-at-Linstead-Market_17548474

DreadBrown

Feed the children

Not really news but this market is minutes away from my dads house and I got a cousin who trades there so I had to represent. Times hard all around as produce and other products are cheaper imported from the US undercutting domestic sellers

Last edited:

Not really news but this market is minutes away from my dads house and I got a cousin who trades there so I had to represent. Times hard all around as produce and other products are cheaper imported from the US undercutting domestic sellers

You in Jamaica currently?

DreadBrown

Feed the children

Nah I live in the UK born here aswell my parents came here in the 70's. I try to go back often as I can but air fair is far from cheap, was there last August 2013. My dad is out there at least twice a year though.