[...] few may know that one of the most influential and critically acclaimed Puerto Rican actors in the history of Hollywood was actually a black man — Juano Hernández — whose career in the pictures predated that of Ferrer by over twenty years.

Largely forgotten even in his native Puerto Rico, Hernández is considered by film historians to be a trailblazing actor who revolutionized the representation of black characters on the big screen. With a prolific career spanning over 50 years, his breakout role in a filmed adaptation of William Faulkner’s Intruder in the Dust (1949) earned him a Golden Globe nomination and glowing praise from international critics and even Faulkner himself.

[...] After a brief appearance as a Mexican soldier in the infamous 1914 feature The Life of General Villa, Hernández began his career on the big screen acting in producer-director Oscar Micheaux’ depression-era “race films” which featured black performers and were targeted towards black audiences.

Famed for his big, sympathetic eyes, commanding voice, and incomparable stage presence, Hernández’s eventual mainstream success with Intruder in the Dust opened the door for a series of groundbreaking roles under the guidance of illustrious directors like Michael Curtiz and Sydney Lumet. Later in life, Hernández returned to his native Puerto Rico where he taught English at the University of Puerto Rico and served as a mentor for young artists and filmmakers like Jacobo Morales. He continued acting in Hollywood productions until his death in 1970.

A Look Back at the Films of Juano Hernández, Hollywood's Very First Afro-Latino Movie Star

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

28 DAYS OF MELANIN: THE BLACK HISTORY MONTH APPRECIATION

- Thread starter m0rninggl0ry

- Start date

More options

Who Replied?m0rninggl0ry

All Star

João da Cruz e Sousa (November 24, 1861 – March 19, 1898) was a Brazilian poet and journalist, famous for being one of the first Brazilian Symbolist poets ever. A descendant of African slaves, he has received the epithets of "Black Dante" and "Black Swan". He is the patron of the 15th chair of the Academia Catarinense de Letras.

Fabiana Marcelino Claudino (born 24 January 1985) is a volleyball player from Brazil, who made her debut for the Brazilian national team against Croatia. She captained Brazil to the gold medal at the 2012 Olympics.

Emmanuel "Manno" Sanon (June 25, 1951 – February 21, 2008) was a Haitian footballer who played as a striker. He starred in the Haiti national football team winning the 1973 CONCACAF Championship and scored the team's only two goals in its history during the 1974 FIFA World Cup in Germany, where he became notorious for snapping Italy's Dino Zoff's no-goal 1,142 minute streak from a lead pass from Philippe Vorbe.

Sanon won his home national championship in 1971 with top-level Don Bosco. He then won the Belgian Cup in the Belgian Pro League in 1979 with the K. Beerschot V.A.C..

Sanon is among the "Les 100 Héros de la Coupe du Monde" (100 Heroes of the World Cup), which included the top 100 World Cup Players from 1930 to 1990, a list drawn up in 1994 by the France Football magazine based exclusively on their performances at World Cup level.

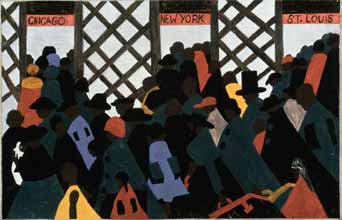

Jacob Lawrence (September 7, 1917 – June 9, 2000) was an African-American painter known for his portrayal of African-American life. But not only was he a painter, storyteller, and interpreter; he also was an educator. Lawrence referred to his style as "dynamic cubism," though by his own account the primary influence was not so much French art as the shapes and colors of Harlem.He brought the African-American experience to life using blacks and browns juxtaposed with vivid colors. He also taught, and spent 15 years as a professor at the University of Washington.

Lawrence is among the best-known 20th-century African-American painters. He was 23 years old when he gained national recognition with his 60-panel Migration Series, painted on cardboard. The series depicted the Great Migration of African Americans from the rural South to the urban North. A part of this series was featured in a 1941 issue of Fortune Magazine. The collection is now held by two museums. Lawrence's works are in the permanent collections of numerous museums, including the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney Museum, the Phillips Collection, Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Brooklyn Museum, and Reynolda House Museum of American Art. He is widely known for his modernist illustrations of everyday life as well as epic narratives of African American history and historical figures.

This thread is so beautiful. @m0rninggl0ry do you want this thread to basically/mainly be achievements/celebration or can it include some tragic stories?

m0rninggl0ry

All Star

This thread is so beautiful. @m0rninggl0ry do you want this thread to basically/mainly be achievements/celebration or can it include some tragic stories?

Thanks sis for your contribution

I prefer achievements but we have went thru tragedy that affects us today, globally. You may but put out information that we never knew about not the TULSA AND ROSEWOOD tragedies.

TezMilli

All Star

Henrietta Lacks

Henrietta Lacks was born Loretta Pleasant on August 1, 1920, in Roanoke, Virginia. At some point, she changed her name to Henrietta. After the death of her mother in 1924, Henrietta was sent to live with her grandfather in a log cabin that had been the slave quarters of a white ancestor's plantation. Henrietta Lacks shared a room with her first cousin, David "Day" Lacks. In 1935, the cousins had a son they called Lawrence. Henrietta was 14. The couple had a daughter, Elsie, in 1939, and married in 1941.

Henrietta and David moved to Maryland at the urging of another cousin, Fred Garret. There, they had three more children: David Jr., Deborah and Joseph. They placed their daughter Elsie, who was developmentally disabled, in the Hospital for the Negro Insane.

On January 29, 1951, Lacks went to Johns Hopkins Hospital to diagnose abnormal pain and bleeding in her abdomen. Physician Howard Jones quickly diagnosed her with cervical cancer. During her subsequent radiation treatments, doctors removed two cervical samples from Lacks without her knowledge. She died at Johns Hopkins on October 4, 1951, at the age of 31.

The cells from Lacks's tumor made their way to the laboratory of researcher Dr. George Otto Gey. Gey noticed an unusual quality in the cells. Unlike most cells, which survived only a few days, Lacks's cells were far more durable. Gey isolated and multiplied a specific cell, creating a cell line. He dubbed the resulting sample HeLa, derived from the name Henrietta Lacks.

The HeLa strain revolutionized medical research. Jonas Salk used the HeLa strain to develop the polio vaccine, sparking mass interest in the cells. Scientists cloned the cells in 1955, as demand grew. Since that time, over ten thousand patents involving HeLa cells have been registered. Researchers have used the cells to study disease and to test human sensitivity to new products and substances.

Black Haven

We will find another road to glory!!!

A bit controversial but you can't deny his legacy.

Robert Goines, the African American writer who turned out 16 novels under his own name and his pseudonym "Al C. Clark" in his brief literary career, was born in Detroit, Michigan in 1937. He was sent to Catholic school by his family, who expected young Donald to get his education and eventually work in the family's laundry business. In 1952, Goines enlisted in the US Air Force at the age of 17, lying about his age to enlist. During his three-year stint in USAF blues, he became a heroin addict while stationed in Korea and Japan, a monkey on his back that clung to him when he rejoined civilian life in 1955. Eventually, the monkey was demanding a century-note's worth of junk a day to remain calm and not run his claws through Goines' body and soul.

Robert Goines, the African American writer who turned out 16 novels under his own name and his pseudonym "Al C. Clark" in his brief literary career, was born in Detroit, Michigan in 1937. He was sent to Catholic school by his family, who expected young Donald to get his education and eventually work in the family's laundry business. In 1952, Goines enlisted in the US Air Force at the age of 17, lying about his age to enlist. During his three-year stint in USAF blues, he became a heroin addict while stationed in Korea and Japan, a monkey on his back that clung to him when he rejoined civilian life in 1955. Eventually, the monkey was demanding a century-note's worth of junk a day to remain calm and not run his claws through Goines' body and soul.

Unable to get straight, it was hard to fly right with such a burden, even for an ex-air man. Like many addicts, Goines turned to crime to support his jones. In addition to theft and armed robbery, he also engaged in bootlegging, numbers running and pimping. In and out of jail, he was incarcerated for a total of six and one-half of the first 15 years after he left the service. He wrote his first two novels while in stir.

Goines had first, while barred up and reduced to wearing prison stripes, tried his hand at writing Westerns, but he was uninspired by the genre. However, he found his muse when he discovered the writings of the ultra-cool Iceberg Slim, the legendary pimp and raconteur. Iceberg Slim's works such as his seminal "Pimp" inspired Goines to write the semi-autobiographical "Whoreson," a novel about a mack born to his trade as the son of a street-walker. "Whoreson" was brought out in 1972 by Slim's publisher, Holloway House, which specialized in African American works. It was his second published novel, after 1971's "Dopefiend: The Story of a Black Junkie."

Goines was sprung from the joint in 1970. He began writing at a frenzied pace for the four years that were allotted to him in this vale of tears, publishing 16 paperback originals with Holloway House. Still addicted to junk, Goines was disciplined enough to keep to a strict schedule, writing in the morning before giving over the rest of his day to letting the lady run her quick-silvery hands through his being. Writing at a furious pace, he could turn out a novel in as little as a month. His style is unpolished, his syntax rough, and his words liberally dependent on the language of the streets, shot through with black dialect (Ebonics). His novels are peopled by pimps, `hos, thieves, hitters and dope fiends, struggling to survive in a ghetto jungle beset with merciless predators. The books were written for an audience that had lived side-by-side with such creatures and to whom Goines' characters could never be deemed "exotics," readers to whom violence was or had been a part of life, not something wholly fictional.

The novels he published under his own name are about the "lumpenproleteriat," the criminal underclass. Under the name "Al C. Clark," Goines wrote five novels about a black revolutionary cat called Kenyatta. Unlike Goines' gangstas, Kenyatta - named after the great African freedom fighter Jomo Kenyatta - takes an active stance against exploitation and the depredations of inner-city life. He opposes the Establishment and is a sworn enemy of white cops. The head a black militant organization dedicated to the Herculean task of douching out the ghettos of drugs and prostitution, Kenyatta is killed in a shootout in the last book of the series, "Kenyatta's Last Hit" (1975).

Of his oeuvre, Andrew Calcutt and Richard Shepard in "Cult Fiction" (1998) opine, "Donald Goines wrote fiction the way other people package meat. There is little point in picking any of his titles as outstanding, since they are all formulaic. Equally, however, they are outstanding in that they are street-real and avoid the romanticism of many of the films and books about black life in America."

Between five and ten million of Goines books have been sold, though his work did not receive much critical attention until the the hip hop generation, which he influenced, became a cultural phenomenon. Goines' books have inspired gangsta rappers from Tupac Shakur to Noreaga as a new generation of rap-influenced African Americans adopted the long-gone writer as part of their cultural heritage. Goines' works reflect the anger and frustration of African Americans as a people. The hip hop generation was sympathetic and accepting of Goines' rejection of the values of white society.

The rapper DMX adapted Goines 1974 "Never Die Alone" into a movie, the first made from one of his novels. In the film, DMX plays King David, a gangster seeking redemption. The movie, directed by Ernest dikkerson, was financed by Fox/Searchlight Films and DMX's own Bloodline Films. No stranger to legal problems, DMX made the film because he identified with the writer.

Another rapper, Kool G Rap, one of the pioneers of street-hop, identifies himself as Goines' heir. Calling himself the "Donald Goines of Rap" due to his ability as a story-teller, Kool G says, "Before G Rap, they weren't talking about selling drugs in the street, murdering; they weren't doing nothing relating to the streets. They were talking about making new dances. But with Donald Goines, I took what I was seeing and tried to make it visual like him."

While hip hop as an art form cannot be considered a direct descendant of writers like Goines or Iceberg Slim, they did have a major influence on gangsta rappers. Nas and Royce Da 5' 9" both have songs called "Black Girl Lost," which is the title of a Goines book.

Donald Goines and his wife were shot to death on October 21, 1974 under circumstances that remain a mystery. Some people believe they were killed in a drug deal that went wrong. Their grandson, Donald Goines III, was murdered in 1992, part of the destruction of young African American lives that has not abated since long before the founding of the Republic, a country whose Constitution deemed African Americans as 3/5ths of a person for the purpose of establishing the apportionment of Congressional representation but did not give them any legal or social rights.

Thirty years after his death, Donald Goines's novels are as relevant as they were in the early 70s, offering a picture of a lifestyle immersed in violence, sex and drugs. It's a life - often sacrificed to the exigencies of the street - that has since become glamorized and more appealing for a new generation of African Americans and white "wiggah" wannabes due to the mainstream commercialization of gangsta rap by urban media moguls more concerned with Big Buck$ than social justice.

Unable to get straight, it was hard to fly right with such a burden, even for an ex-air man. Like many addicts, Goines turned to crime to support his jones. In addition to theft and armed robbery, he also engaged in bootlegging, numbers running and pimping. In and out of jail, he was incarcerated for a total of six and one-half of the first 15 years after he left the service. He wrote his first two novels while in stir.

Goines had first, while barred up and reduced to wearing prison stripes, tried his hand at writing Westerns, but he was uninspired by the genre. However, he found his muse when he discovered the writings of the ultra-cool Iceberg Slim, the legendary pimp and raconteur. Iceberg Slim's works such as his seminal "Pimp" inspired Goines to write the semi-autobiographical "Whoreson," a novel about a mack born to his trade as the son of a street-walker. "Whoreson" was brought out in 1972 by Slim's publisher, Holloway House, which specialized in African American works. It was his second published novel, after 1971's "Dopefiend: The Story of a Black Junkie."

Goines was sprung from the joint in 1970. He began writing at a frenzied pace for the four years that were allotted to him in this vale of tears, publishing 16 paperback originals with Holloway House. Still addicted to junk, Goines was disciplined enough to keep to a strict schedule, writing in the morning before giving over the rest of his day to letting the lady run her quick-silvery hands through his being. Writing at a furious pace, he could turn out a novel in as little as a month. His style is unpolished, his syntax rough, and his words liberally dependent on the language of the streets, shot through with black dialect (Ebonics). His novels are peopled by pimps, `hos, thieves, hitters and dope fiends, struggling to survive in a ghetto jungle beset with merciless predators. The books were written for an audience that had lived side-by-side with such creatures and to whom Goines' characters could never be deemed "exotics," readers to whom violence was or had been a part of life, not something wholly fictional.

The novels he published under his own name are about the "lumpenproleteriat," the criminal underclass. Under the name "Al C. Clark," Goines wrote five novels about a black revolutionary cat called Kenyatta. Unlike Goines' gangstas, Kenyatta - named after the great African freedom fighter Jomo Kenyatta - takes an active stance against exploitation and the depredations of inner-city life. He opposes the Establishment and is a sworn enemy of white cops. The head a black militant organization dedicated to the Herculean task of douching out the ghettos of drugs and prostitution, Kenyatta is killed in a shootout in the last book of the series, "Kenyatta's Last Hit" (1975).

Of his oeuvre, Andrew Calcutt and Richard Shepard in "Cult Fiction" (1998) opine, "Donald Goines wrote fiction the way other people package meat. There is little point in picking any of his titles as outstanding, since they are all formulaic. Equally, however, they are outstanding in that they are street-real and avoid the romanticism of many of the films and books about black life in America."

Between five and ten million of Goines books have been sold, though his work did not receive much critical attention until the the hip hop generation, which he influenced, became a cultural phenomenon. Goines' books have inspired gangsta rappers from Tupac Shakur to Noreaga as a new generation of rap-influenced African Americans adopted the long-gone writer as part of their cultural heritage. Goines' works reflect the anger and frustration of African Americans as a people. The hip hop generation was sympathetic and accepting of Goines' rejection of the values of white society.

The rapper DMX adapted Goines 1974 "Never Die Alone" into a movie, the first made from one of his novels. In the film, DMX plays King David, a gangster seeking redemption. The movie, directed by Ernest dikkerson, was financed by Fox/Searchlight Films and DMX's own Bloodline Films. No stranger to legal problems, DMX made the film because he identified with the writer.

Another rapper, Kool G Rap, one of the pioneers of street-hop, identifies himself as Goines' heir. Calling himself the "Donald Goines of Rap" due to his ability as a story-teller, Kool G says, "Before G Rap, they weren't talking about selling drugs in the street, murdering; they weren't doing nothing relating to the streets. They were talking about making new dances. But with Donald Goines, I took what I was seeing and tried to make it visual like him."

While hip hop as an art form cannot be considered a direct descendant of writers like Goines or Iceberg Slim, they did have a major influence on gangsta rappers. Nas and Royce Da 5' 9" both have songs called "Black Girl Lost," which is the title of a Goines book.

Donald Goines and his wife were shot to death on October 21, 1974 under circumstances that remain a mystery. Some people believe they were killed in a drug deal that went wrong. Their grandson, Donald Goines III, was murdered in 1992, part of the destruction of young African American lives that has not abated since long before the founding of the Republic, a country whose Constitution deemed African Americans as 3/5ths of a person for the purpose of establishing the apportionment of Congressional representation but did not give them any legal or social rights.

Thirty years after his death, Donald Goines's novels are as relevant as they were in the early 70s, offering a picture of a lifestyle immersed in violence, sex and drugs. It's a life - often sacrificed to the exigencies of the street - that has since become glamorized and more appealing for a new generation of African Americans and white "wiggah" wannabes due to the mainstream commercialization of gangsta rap by urban media moguls more concerned with Big Buck$ than social justice.

m0rninggl0ry

All Star

Willa Beatrice Player (August 9, 1909 - August 29, 2003) was an African-American educator, college administrator, college president, civil rights activist, and federal appointee. Player was the first African American woman to become president of a four-year fully accredited liberal arts college when she took the position at Bennett College for Women in Greensboro, North Carolina.

In her career at Bennett College, Player had served as a teacher and then in progressively responsible administrator positions. From 1955 to 1966, Player served as president of the historically black college, during a period of heightened civil rights activism in the South. She supported Bennett students who took part in the lengthy sit-ins started by the Greensboro Four to achieve integration of lunch counters in downtown stores.

Player had a strong education, earning a BA degree from Ohio Wesleyan College, a Master's from Oberlin College, a Certificat d'Études at University of Grenoble in France, and a PhD from Columbia University. After leaving the Bennett presidency, Player was appointed in 1966 by President Lyndon B. Johnson as the first female Director of the Division of College Support in the United States Department of Health, Education and Welfare, serving until 1986.

Paul Q. Judge (born 1977 in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, U.S.) is an award-winning technologist, entrepreneur, and speaker. Judge was a technical expert for the Federal Trade Commission in the 2005 Report to Congress on the Effectiveness of the CAN-SPAM Act. In 2003, he founded the Anti-Spam Research Group in the Internet Research Task Force.

Judge attended Morehouse College in Atlanta earning a B.S. in Computer Science with a minor in Mathematics in three years. He then matriculated at Georgia Tech, completing M.S. and Ph.D. degrees in Computer Science in 2002. Judge then did post doctorate work at Georgia Tech in 2003.

Judge joined the founding team of CipherTrust in 2000 and served as Chief Technology Officer until the company was acquired in 2006. Judge served as Senior Vice President and Chief Technology Officer of Secure Computing Corp until 2007. Judge founded Purewire in 2007, acquired by Barracuda Networks in 2009. He is cofounder and Executive Chairman of Pindrop, provider of phone anti-fraud and authentication solutions, founded in 2011. Most recently he is co-founder of Luma, a wireless networking company.

Judge has been awarded six US patents and has 19 other US patents pending. These include: No. 7,225,466 Systems and methods for message threat management, No. 7,213,260 Systems and methods for upstream threat pushback, No. 7,124,438 Systems and methods for anomaly detection in patterns of monitored communications,No. 7,096,498 Systems and methods for message threat management, No. 7,089,590 Systems and methods for adaptive message interrogation through multiple queues, and No. 6,941,467 Systems and methods for adaptive message interrogation through multiple queues.

Self_Born7

SUN OF MAN

this lovely lady, read her auto bio, years back and instantly fell in love with this queen... I admired her so much, i named my first child, my daughter after her

On May 2, 1973, Black Panther Assata Shakur (aka JoAnne Chesimard) lay in a hospital, close to death, handcuffed to her bed, while local, state, and federal police attempted to question her about the shootout on the New Jersey Turnpike that had claimed the life of a white state trooper. Long a target of J. Edgar Hoover's campaign to defame, infiltrate, and criminalize Black nationalist organizations and their leaders, Shakur was incarcerated for four years prior to her conviction on flimsy evidence in 1977 as an accomplice to murder.

This intensely personal and political autobiography belies the fearsome image of JoAnne Chesimard long projected by the media and the state. With wit and candor, Assata Shakur recounts the experiences that led her to a life of activism and portrays the strengths, weaknesses, and eventual demise of Black and White revolutionary groups at the hand of government officials. The result is a signal contribution to the literature about growing up Black in America that has already taken its place alongside The Autobiography of Malcolm X and the works of Maya Angelou.

Two years after her conviction, Assata Shakur escaped from prison. She was given political asylum by Cuba, where she now resides.

On May 2, 1973, Black Panther Assata Shakur (aka JoAnne Chesimard) lay in a hospital, close to death, handcuffed to her bed, while local, state, and federal police attempted to question her about the shootout on the New Jersey Turnpike that had claimed the life of a white state trooper. Long a target of J. Edgar Hoover's campaign to defame, infiltrate, and criminalize Black nationalist organizations and their leaders, Shakur was incarcerated for four years prior to her conviction on flimsy evidence in 1977 as an accomplice to murder.

This intensely personal and political autobiography belies the fearsome image of JoAnne Chesimard long projected by the media and the state. With wit and candor, Assata Shakur recounts the experiences that led her to a life of activism and portrays the strengths, weaknesses, and eventual demise of Black and White revolutionary groups at the hand of government officials. The result is a signal contribution to the literature about growing up Black in America that has already taken its place alongside The Autobiography of Malcolm X and the works of Maya Angelou.

Two years after her conviction, Assata Shakur escaped from prison. She was given political asylum by Cuba, where she now resides.

Keeth Thomas Smart[1] (born July 29, 1978) is a US sabre fencer who became the first African American to gain the sport's #1 ranking for males. He received a silver medal at the 2008 Olympic Games in Beijing

In 2002 and 2004, Smart won the US national sabre championship. In 2003, he became the first American to be named the top-ranked fencer internationally.

Smart graduated from Brooklyn Technical High School in 1996.[5] He graduated from St. John's University in New York

, majoring in finance.[5] He received his MBA from Columbia University in 2010 and now works at a major bank.[4]

, majoring in finance.[5] He received his MBA from Columbia University in 2010 and now works at a major bank.[4]Graman Quassi

A black man in eleborate European dress with a feathered cocked hat, watch, and a walking stick stands before a dwelling, fortifications with a Dutch flag, and soldiers drilling. Quacy, or Kwasi, was born in West Africa ca. 1690 and transported to Suriname as a child. By 1730, he had discovered the medicinal properties of the Quassiehout, Quassia amara, and served during the next six decades as the colony's leading medicine man with vast influence over all the inhabitants, black, white, and native, of Suriname. He was also the colony's principal intermediary in dealing with maroons*, serving first as a scout, then a negotiator, and then as an advisor to the Rangers. Kwasi was manumitted*, became a planter, and remained active well into his nineties.

http://bibliodyssey.blogspot.com.br/2007/08/surinam-slave-trade.html

Black Haven

We will find another road to glory!!!

Benjamin Banneker

Astronomer, Scientist (1731-1806)Benjamin Banneker was a largely self-educated mathematician, astronomer, compiler of almanacs and writer.

Synopsis

Benjamin Banneker was born on November 9, 1731, in Ellicott's Mills, Maryland. A free black man who owned a farm near Baltimore, Banneker was largely self-educated in astronomy and mathematics. He was later called upon to assist in the surveying of territory for the construction of the nation's capital. He also became an active writer of almanacs and exchanged letters with Thomas Jefferson, politely challenging him to do what he could to ensure racial equality. Banneker died on October 9, 1806.

Background and Early Years

Born on November 9, 1731, in Ellicott's Mills, Maryland, Benjamin Banneker was the son of an ex-slave named Robert and his wife, Mary Banneky. Mary was the daughter of an Englishwoman named Molly Welsh, a former indentured servant, and her husband, Bannka, an ex-slave whom she freed and who asserted that he came from tribal royalty in West Africa.

Because both of his parents were free, Benjamin escaped the wrath of slavery as well. He was taught to read by his maternal grandmother and for a very short time attended a small Quaker school. Banneker was primarily self-educated, a fact that did little to diminish his brilliance. His early accomplishments included constructing an irrigation system for the family farm and a wooden clock that was reputed to keep accurate time and ran for more than 50 years until his death. In addition, Banneker taught himself astronomy and accurately forecasted lunar and solar eclipses. After his father's passing, he ran his own farm for years, cultivating a business selling tobacco via crops.

Interests in Astronomy and Surveying

Banneker's talents and intelligence eventually came to the attention of the Ellicott family, entrepreneurs who had made a name and fortune by building a series of gristmills in the Baltimore area in the 1770s. George Ellicott had a large personal library and loaned Banneker numerous books on astronomy and other fields.

In 1791, Andrew Ellicott, George’s cousin, hired Banneker to assist in surveying territory for the nation’s capital city. He worked in the observatory tent using a zenith sector to record the movement of the stars. However, due to a sudden illness, Banneker was only able to work for Ellicott for about three months.

Popular Almanacs

Banneker's true acclaim, however, came from his almanacs, which he published for six consecutive years during the later years of his life, between 1792 and 1797. These handbooks included his own astronomical calculations as well as opinion pieces, literature and medical and tidal information, with the latter particularly useful to fishermen. Outside of his almanacs, Banneker also published information on bees and calculated the cycle of the 17-year locust.

Letter to Jefferson

Benjamin Banneker's accomplishments extended into other realms as well, including civil rights. In 1791, Thomas Jefferson was secretary of state and Banneker considered the respected Virginian, though a slaveholder, to also be open to viewing African Americans as more than slaves. Thus, he wrote Jefferson a letter hoping that he would “readily embrace every opportunity to eradicate that train of absurd and false ideas and opinions which so generally prevail with respect to us." To further support his point, Banneker included a handwritten manuscript of an almanac for 1792, containing his astronomical calculations.

In his letter, Banneker acknowledged he was “of the African race” and a free man. He recognized that he was taking “a liberty” writing to Jefferson, which would be unacceptable considering “the almost general prejudice and prepossession which is so prevalent in the world against those of my complexion.” Banneker then respectfully chided Jefferson and other patriots for their hypocrisy, enslaving people like him while fighting the British for their own independence.

Jefferson quickly acknowledged Banneker's letter, writing a response. He told Banneker that he took “the liberty of sending your almanac to Monsieur de Condorcet [secretary of the French Academy of Sciences]...because I considered it as a document to which your whole colour had a right for their justification against the doubts which have been entertained of them.” Banneker published Jefferson’s letter alongside his original piece of correspondence in his 1793 almanac. Banneker's outspokenness with regard to the issue of slavery earned him the widespread support of the abolitionist societies in Maryland and Pennsylvania, both of which helped him publish his almanac.

Below is a letter from Jefferson to Banneker dated August 30, 1791 from the Library of Congress:

I thank you sincerely for your letter of the 19th. instant and for the Almanac it contained. no body wishes more than I do to see such proofs as you exhibit, that nature has given to our black brethren, talents equal to those of the other colours of men, & that the appearance of a want of them is owing merely to the degraded condition of their existence both in Africa & America. I can add with truth that no body wishes more ardently to see a good system commenced for raising the condition both of their body & mind to what it ought to be, as fast as the imbecillity of their present existence, and other circumstance which cannot be neglected, will admit. I have taken the liberty of sending your almanac to Monsieur de Condorcet, Secretary of the Academy of sciences at Paris, and member of the Philanthropic society because I considered it as a document to which your whole colour had a right for their justification against the doubts which have been entertained of them. I am with great esteem, Sir, Your most obedt. humble servt. Th. Jefferson

Later Life and Death

Never married, Benjamin Banneker continued to conduct his scientific studies throughout his life. By 1797, sales of his almanac had declined and he discontinued publication. In the following years, he sold off much of his farm to the Ellicotts and others to make ends meet, continuing to live in his log cabin.

On October 9, 1806, after his usual morning walk, Banneker died in his sleep, just a month short of his 75th birthday. In accordance with his wishes, all the items that had been on loan from his neighbor, George Ellicott, were returned by Banneker’s nephew. Also included was Banneker’s astronomical journal, providing future historians one of the few records of his life known to exist.

On Tuesday, October 11, at the family burial ground a few yards from this house, Benjamin Banneker was laid to rest. During the services, mourners were startled to see his house had caught on fire, quickly burning down. Nearly everything was destroyed, including his personal effects, furniture and wooden clock. The cause of the fire was never determined.

Benjamin Banneker’s life was remembered in an obituary in the Federal Gazette of Philadelphia and has continued to be written about over the ensuing two centuries. With limited materials having been preserved related to Banneker's life and career, there's been a fair amount of legend and misinformation presented. In 1972, scholar Sylvio A. Bedini published an acclaimed biography on the 17th-century icon—The Life of Benjamin Banneker: The First African-American Man of Science. A revised edition appeared in 1999.

Black Haven

We will find another road to glory!!!

This man is truly underrated

GranvilleT. Woods

GranvilleT. Woods

Inventor (1856-1910)Known as "Black Edison," Granville Woods was an African-American inventor who made key contributions to the development of the telephone, street car and more.

Synopsis

Granville T. Woods was born in Columbus, Ohio, on April 23, 1856, to free African-Americans. He held various engineering and industrial jobs before establishing a company to develop electrical apparatus. Known as "Black Edison," he registered nearly 60 patents in his lifetime, including a telephone transmitter, a trolley wheel and the multiplex telegraph (over which he defeated a lawsuit by Thomas Edison). Woods died in 1910.

Early Life

Born in Columbus, Ohio, on April 23, 1856, to free African Americans, Granville T. Woods received little schooling as a young man and, in his early teens, took up a variety of jobs, including as a railroad engineer in a railroad machine shop, as an engineer on a British ship in a steel mill, and as a railroad worker. From 1876 to 1878, Woods lived in New York City, taking courses in engineering and electricity—a subject that he realized, early on, held the key to the future.

Back in Ohio in the summer of 1878, Woods was employed for eight months by the Springfield, Jackson and Pomeroy Railroad Company to work at the pumping stations and the shifting of cars in the city of Washington Court House, Ohio. He was then employed by the Dayton and Southeastern Railway Company as an engineer for 13 months.

During this period, while traveling between Washington Court House and Dayton, Woods began to form ideas for what would later be credited as his most important invention: the "inductor telegraph." He worked in the area until the spring of 1880, and then moved to Cincinnati.

Early Inventing Career

Living in Cincinnati, Woods eventually set up his own company to develop, manufacture and sell electrical apparatus, and in 1889, he filed his first patent for an improved steam boiler furnace. His later patents were mainly for electrical devices, including his second invention, an improved telephone transmitter.

The patent for his device, which combined the telephone and telegraph, was bought by Alexander Graham Bell, and the payment freed Woods to devote himself to his own research. One of his most important inventions was the "troller," a grooved metal wheel that allowed street cars (later known as "trolleys") to collect electric power from overhead wires.

Induction Telegraph

Woods's most important invention was the multiplex telegraph, also known as the "induction telegraph," or block system, in 1887. The device allowed men to communicate by voice over telegraph wires, ultimately helping to speed up important communications and, subsequently, preventing crucial errors such as train accidents. Woods defeated Thomas Edison's lawsuit that challenged his patent, and turned down Edison's offer to make him a partner. Thereafter, Woods was often known as "Black Edison."

After receiving the patent for the multiplex telegraph, Woods reorganized his Cincinnati company as the Woods Electric Co. In 1890, he moved his own research operations to New York City, where he was joined by a brother, Lyates Woods, who also had several inventions of his own.

Woods's next most important invention was the power pick-up device in 1901, which is the basis of the so-called "third rail" currently used by electric-powered transit systems. From 1902 to 1905, he received patents for an improved air-brake system.

Death and Legacy

By the time of his death, on January 30, 1910, in New York City, Granville T. Woods had invented 15 appliances for electric railways. received nearly 60 patents, many of which were assigned to the major manufacturers of electrical equipment that are a part of today's daily life.

Inventor (1856-1910)Known as "Black Edison," Granville Woods was an African-American inventor who made key contributions to the development of the telephone, street car and more.

Synopsis

Granville T. Woods was born in Columbus, Ohio, on April 23, 1856, to free African-Americans. He held various engineering and industrial jobs before establishing a company to develop electrical apparatus. Known as "Black Edison," he registered nearly 60 patents in his lifetime, including a telephone transmitter, a trolley wheel and the multiplex telegraph (over which he defeated a lawsuit by Thomas Edison). Woods died in 1910.

Early Life

Born in Columbus, Ohio, on April 23, 1856, to free African Americans, Granville T. Woods received little schooling as a young man and, in his early teens, took up a variety of jobs, including as a railroad engineer in a railroad machine shop, as an engineer on a British ship in a steel mill, and as a railroad worker. From 1876 to 1878, Woods lived in New York City, taking courses in engineering and electricity—a subject that he realized, early on, held the key to the future.

Back in Ohio in the summer of 1878, Woods was employed for eight months by the Springfield, Jackson and Pomeroy Railroad Company to work at the pumping stations and the shifting of cars in the city of Washington Court House, Ohio. He was then employed by the Dayton and Southeastern Railway Company as an engineer for 13 months.

During this period, while traveling between Washington Court House and Dayton, Woods began to form ideas for what would later be credited as his most important invention: the "inductor telegraph." He worked in the area until the spring of 1880, and then moved to Cincinnati.

Early Inventing Career

Living in Cincinnati, Woods eventually set up his own company to develop, manufacture and sell electrical apparatus, and in 1889, he filed his first patent for an improved steam boiler furnace. His later patents were mainly for electrical devices, including his second invention, an improved telephone transmitter.

The patent for his device, which combined the telephone and telegraph, was bought by Alexander Graham Bell, and the payment freed Woods to devote himself to his own research. One of his most important inventions was the "troller," a grooved metal wheel that allowed street cars (later known as "trolleys") to collect electric power from overhead wires.

Induction Telegraph

Woods's most important invention was the multiplex telegraph, also known as the "induction telegraph," or block system, in 1887. The device allowed men to communicate by voice over telegraph wires, ultimately helping to speed up important communications and, subsequently, preventing crucial errors such as train accidents. Woods defeated Thomas Edison's lawsuit that challenged his patent, and turned down Edison's offer to make him a partner. Thereafter, Woods was often known as "Black Edison."

After receiving the patent for the multiplex telegraph, Woods reorganized his Cincinnati company as the Woods Electric Co. In 1890, he moved his own research operations to New York City, where he was joined by a brother, Lyates Woods, who also had several inventions of his own.

Woods's next most important invention was the power pick-up device in 1901, which is the basis of the so-called "third rail" currently used by electric-powered transit systems. From 1902 to 1905, he received patents for an improved air-brake system.

Death and Legacy

By the time of his death, on January 30, 1910, in New York City, Granville T. Woods had invented 15 appliances for electric railways. received nearly 60 patents, many of which were assigned to the major manufacturers of electrical equipment that are a part of today's daily life.

They gave black people the shortest month

Black History Month - Wikipedia

The precursor to Black History Month was created in 1926 in the United States, when historian Carter G. Woodson and the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History announced the second week of February to be "Negro History Week."[1] This week was chosen because it coincided with the birthday of Abraham Lincoln on February 12 and of Frederick Douglass on February 14, both of which dates Black communities had celebrated together since the late 19th century.[1]

FLORIDA BOI

All Star

André Rebouças

André Rebouças became famous in Rio de Janeiro, at the time capital of the Empire of Brazil, solving the trouble of water supply, bringing it from fountain-heads outside the town. Alongside with Machado de Assis and Olavo Bilac, he was a very important middle class representative with African descent, he also was one of the most important voices for the abolition of slavery in Brazil. He encouraged the career of Carlos Gomes, author of the opera O Guarani. In the 1880's, André Rebouças began to participate actively in the abolitionist cause, he helped to create the Brazilian Anti-Slavery Society, alongside Joaquim Nabuco, José do Patrocínio and others. [...] He was trained at the Military School of Rio de Janeiro and became an engineer after studying in Europe. After returning to Brazil, Reboucas was named a lieutenant in the engineering corps in the 1864 Paraguayan War. During the war, as naval vessels became more and more integral, Reboucas designed an immersible device which could be projected underwater, causing an explosion with any ship it hit. The device became known as the torpedo. After his military career, Reboucas began teaching at the Polytechnical School in Rio de Janeiro and became very wealthy. He used his wealth to aid in the Brazilian abolition movement, trying to end slavery in Brazil. After growing disgusted with conditions in Brazil, Reboucas moved to Funchal, Madeira, off of the coast of Africa where he died in 1898.

ProjectBlackMan.com - The Black Man Hall Of Fame - André Rebouças