OfTheCross

Veteran

Why Gas Prices Are So High

How much people pay for gas is the result of trading on a sprawling international market. Like many other facets of the global economy, it comes down to a matter of supply and demand.

www.nytimes.com

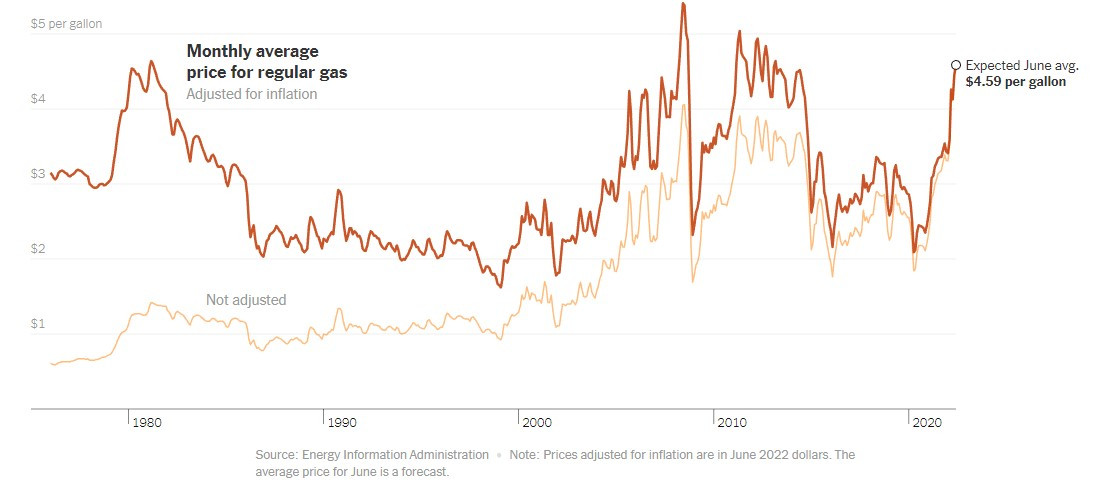

Gas prices in the United States are at record highs. And even when adjusting for inflation, they are on average at levels rarely seen in the last 50 years, including during the energy crisis of the late 1970s. When fuel prices go up, consumers are hurt directly at the pump, but also indirectly when higher transportation costs raise prices on everything from food to diapers to construction materials.

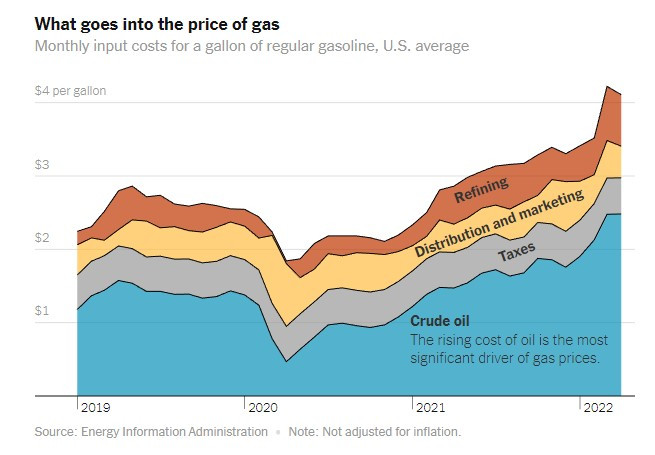

The single biggest factor driving the spike now is the price of crude oil. As of April, according to the Energy Information Administration, the cost of the raw material accounted for 60 percent of the price of a gallon of regular gasoline. That compares to 52 percent the same time a year ago, and just 25 percent in April 2020 — when the pandemic sapped demand for fuel, along with most other goods and commodities.

What goes into the price of gas

Monthly input costs for a gallon of regular gasoline, U.S. average

How much people end up paying for gas is the result of trading that takes place in a sprawling international market for oil and petroleum products. But like many other facets of the global economy, it comes down to supply and demand — and when the balance between those two forces is disrupted, costs inevitably swing.

Expensive oil becomes expensive gas.

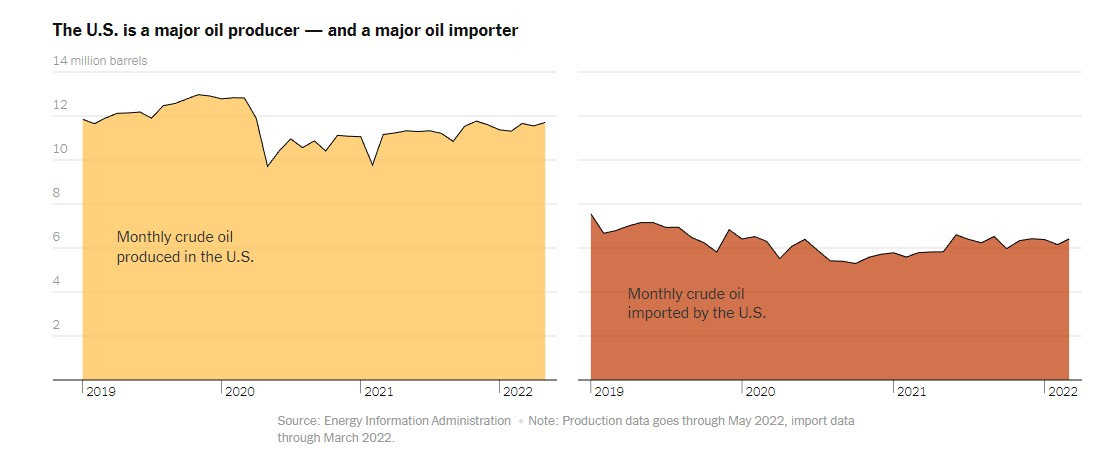

The United States is the world’s largest producer of oil and processed petroleum products. In recent years, it has become a major exporter, sending large quantities to Latin America and Europe.But the United States also buys a lot of oil from other countries. It is the second largest importer in the world after China. That’s partly because American refineries are often set up to process types of oil that are different from those produced in the United States.

It would be expensive and difficult to reconfigure refineries to process more U.S. oil, which is why the United States is likely to continue importing large quantities even if it were to produce more domestically. The United States also uses much more oil than it produces.

Russia, by comparison, is the world’s second largest producer and accounts for roughly one in 10 barrels on the global market. Before the country invaded Ukraine in February, roughly half of Russia’s oil exports went to Europe, representing $10 billion in transactions a month. Last year, about 8 percent of U.S. crude oil imports came from Russia.

The U.S. is a major oil producer — and a major oil importer

Since the beginning of the Ukraine war, Russia has been selling less oil in part because of sanctions imposed by the European Union, United States and other major economies. That has reduced global supplies and led to a jump in prices.

To help ease this growing crisis, President Biden is asking U.S. oil companies and other large producers of oil to increase their output, but it is not having much success. That’s because oil executives are fearful that the price could fall if they increase production too much. And countries like Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates cannot quickly ramp up output enough to offset the expected drop in Russian supplies.

The effort to stabilize the oil market, however, is at odds with Mr. Biden’s stated ambition to move the country to electric cars and renewable energy.

Why the No. 1 oil country is producing less oil.

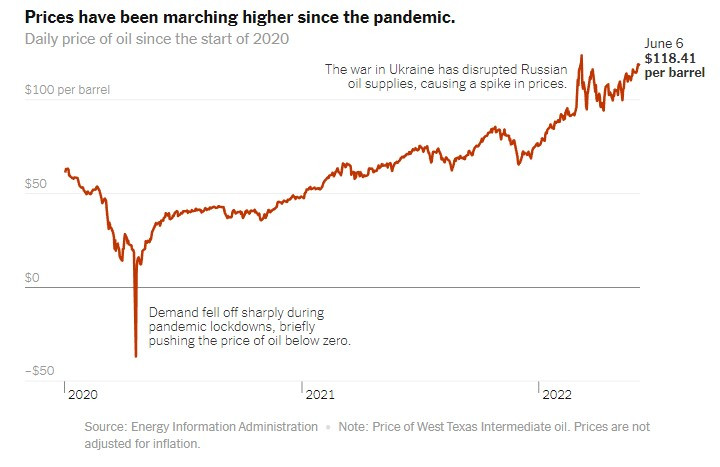

Even before the invasion, prices of oil and gasoline were rising as the world gradually recovered from the Covid pandemic. For a brief moment in 2020, the cost of a barrel of oil fell below zero because storage tanks were full from the lack of demand. Now, commuters and vacationers are back on the road, and offices and industries have reopened.Prices have been marching higher since the pandemic.

Daily price of oil since the start of 2020

There have been two oil price crashes in the past eight years, and many executives believe that another one is inevitable. That has made them hesitant to drill new wells and seriously ramp up production, said Christopher Knittel, an energy economist at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. The lack of investment has led to a decline in output in recent years.

Companies have instead been directing profits to shareholders in the form of dividends or as share buybacks.

“Even though they see high prices today, they're afraid that prices are gonna tank over the life of that well,” Mr. Knittel said of industry executives. “They also have this expectation that electric vehicles are going to continue to grow, which means that 10 years from now, that oil well may not be earning profits. And so all of that is creating a disincentive to drill.”

At the same time, refineries have been steadily shutting down for similar reasons, as oil companies plot a transition to renewables, said John Auers, a vice president at the energy consulting firm Turner and Mason.

The slowdown in domestic activity comes as global refinery capacity is barely meeting market demand. Combined, these conditions can magnify disruptions to global supply.

As the war in Ukraine drags on and Russian production drops, analysts have suggested that the energy market could be fundamentally rewired. Over time, that change in the flow of oil could reduce Russia’s leverage over Europe. But until more supply comes online or demand falls, prices at the pump will likely stay high.