THAT would be hilariousChina stay cooking they're books, I don't think they have over a billion people.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Weakened China won’t overtake US economy ‘until 2080’: Rising debt, ageing population and ongoing property crisis to hold back Asian powerhouse

- Thread starter ☑︎#VoteDemocrat

- Start date

More options

Who Replied?

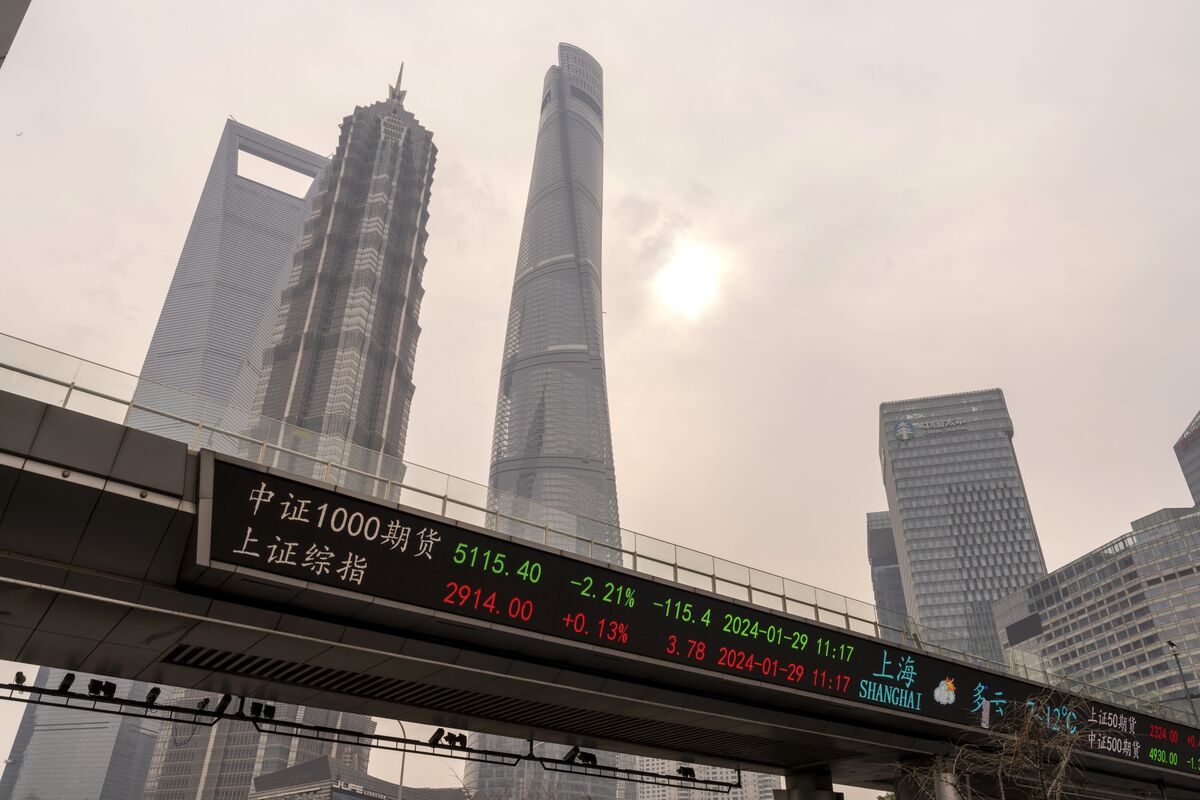

China Tightens Some Trading Restrictions for Domestic and Offshore Investors

China is tightening trading restrictions on domestic institutional investors as well as some offshore units as authorities fight to stem a deepening stock rout, according to people familiar with the matter.

Adding on to previous post.

theworldismine13

God Emperor of SOHH

Sad

ADevilYouKhow

Rhyme Reason

China's economy may not overtake the US, but a Trump presidency would still help Beijing: former IMF official

China will find it hard to sustain a growth rate at 4% to 5% in the next few years, said Eswar Prasad, a Cornell professor and former IMF official.

It pains me to say Hong Kong is over

The stock market is likely to remain in the mire until we see convincing economic measures from Beijing

The writer is a faculty member at Yale, formerly chair of Morgan Stanley Asia, and is the author of “Accidental Conflict: America, China, and the Clash of False Narratives”

There is more to economic vitality than the stock market. But for Hong Kong, the market has always been emblematic of success. Imagine, a small city state with what had long been the world’s fourth largest exchange (it is now fifth, according to Bloomberg data), a global leader of new stock offerings as recently as 2019.

It pains me to admit it, but Hong Kong is now over. A city I once called home and have cherished as a bastion of dynamism has had the world’s worst-performing major stock market over the past quarter of a century. Since the handover to China in 1997, the Hang Seng index has been basically flat, up only about 5 per cent. Over that same period, the S&P 500 has surged more than fourfold; even mainland China’s underperforming Shanghai Composite has far outdistanced the Hong Kong bourse.

Hong Kong’s demise reflects the confluence of three factors. First, domestic politics. For the first 20 years after the handover, its political scene was relatively stable. China was a passive Big Brother. The wheels came off in 2019-20 when, under Carrie Lam, the Hong Kong leadership made the mistake of proposing an extradition arrangement with China that sparked massive pro-democracy demonstrations. China’s response, clamping down through the imposition of a new Beijing-centric national security law, shredded any remaining semblance of local political autonomy. The 50-year transition period to full takeover by the People’s Republic of China had been effectively cut in half.

In the spring of 2019 at the onset of the democracy protests, the Hang Seng index was trading at nearly 30,000. It is now more than 45 per cent below that level at 15,750. Milton Friedman’s favourite free market has been shackled by the deadweight of autocracy.

Second, the China factor. The Hong Kong stock market has long been considered as a levered play on mainland China. For a variety of reasons, the Chinese economy has hit a wall. Structural problems — especially the dreaded three Ds — debt, deflation and demography — have combined with the impact of the Covid pandemic as well as cyclical pressures in the property market and local government financing vehicles. These forces have sparked a three-year bear market that has taken China’s broad CSI 300 index down more than 40 per cent from its spring 2021 peak. Reflecting collateral damage on Chinese enterprises listed in Hong Kong and the city’s China-sensitive services sector, the Hang Seng has fallen 49 per cent over the same period.

Third, global developments. Since 2018, the US-China rivalry has gone from bad to worse. Hong Kong has been trapped in the crossfire. Moreover, America’s “friendshoring” campaign has put pressure on Hong Kong’s Asian allies to pick sides between the US and China. This has driven a wedge between Hong Kong and many of its largest Asian trading partners. Outsize consequences are likely, especially since Hong Kong’s foreign trade totals 192 per cent of its gross domestic product.

There is no easy way out for Hong Kong from the interplay between these three developments. Hong Kong has no political discretion to chart its own course. While the Chinese economic factor might improve, I suspect any rebound is likely to be shortlived in light of lasting headwinds from a shrinking workforce and worrisome productivity prospects. Nor do I see an easy path to the resolution of US-China tensions that would prompt a reversal of the friendshoring trend.

The contrarian would argue, of course, that all this bad news is already discounted in an oversold Hong Kong stock market. China’s recent moves — a raft of government stimulus actions, jawboning, and replacement of the chief securities regulator — might trigger a temporary bounce. However, sceptical investors need to see more from Beijing than just another page from its timeworn countercyclical playbook. Until that happens, Hong Kong is likely to be mired in a trap made in China.

I will never forget my first trip to Hong Kong in the late 1980s. Notwithstanding a frightening, steep landing at the old Kai Tak airport, I was immediately taken with the extraordinary energy of the business community. Back then, Hongkongers had both a vision and a strategy. China was just beginning to stir, and Hong Kong was perfectly positioned as the major beneficiary of what turned into the world’s greatest development miracle. It all worked out brilliantly, for longer than anyone expected. And now it’s over.

Last edited:

China man with the glorious Ls, I’m sure they would love Trump back in office so they can release another virus

U.S. ambassador on why China competition must be managed while keeping "the peace"

The U.S. ambassador to China explains why navigating America's competing interests in China is a difficult balancing act.

the cac mamba

Veteran

china's a pretty bad actorI never understood why we hate China so much but buy everything from them, like how u constantly disrespecting your biggest plug makes no sense.

they treat their people terribly with the censorship, 1 party communism, etc. aggressive polluting and intellectual property theft

they treat their people terribly with the censorship, 1 party communism, etc. aggressive polluting and intellectual property theftand they'd stab us in the back in a second if they could, so i'd say our level of respect is about right