You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

UPDATE 1-Bank of England's Bailey tells pension funds they have 3 days to rebalance

- Thread starter bnew

- Start date

More options

Who Replied?Boris and rishi left the uk in shambles

Godless Socialist CEO

Superstar

England deserves everything they get. Let your hatred of migrants ruin your country brehs

UK Pensions Got Margin Calls

Also bourbon, Hydrogen and Luna.By

Matt Levine

September 29, 2022 at 12:46 PM EDT

LDI

Here is a simple model of a pension fund. You know you will need to pay out a bunch of money 30 years from now, so you buy some 30-year government bonds and hold them to maturity. When the bonds mature in 30 years, you have money, which you give to the pensioners, and you’re done. This model is obviously oversimplified, 1 but it’s a good start.Let me make three points about this model. First, a financial point: Doing a pension fund this way is expensive. Thirty-year UK gilts (government bonds) paid about 2.5% interest this summer. If you want to have £100 in 30 years, and bonds pay 2.5%, you’ll need to put aside about £48 now, which will grow at 2.5% over 30 years into £100. 2 If you are a company or government, you might not be jazzed about putting aside almost half the money now to pay pension obligations in 30 years. What if you bought some stocks instead? If stocks return 8% a year on average, you can put aside just £10 now to get back £100 in 30 years. That’s a much better deal, for you, now. Of course the gilts pay 2.5% guaranteed, while the 8% stock-market return is just a guess; in 30 years, you (and your pension beneficiaries) might regret your riskier choice. But it saves you money now, and it’ll probably work out fine. Or, you know, you do some mix of super-safe gilts and riskier corporate bonds and stocks, etc., still targeting £100 in 30 years but putting less money in now and taking more risk to get there.

Second, a financial-stability point: Structurally, pensions are about the safest form of investing. Most big investors in financial markets are, to some degree or other, structurally short-term, in ways that make markets fragile. Banks borrow most of their money short-term (from depositors, from capital markets), and if there’s a run on the bank then the bank will need to dump assets to pay back depositors. Mutual funds let their investors take money out every day, and if a lot of investors want out then the funds will have to dump stocks to give them their money back. Hedge funds let investors take money out and also tend to borrow money from prime brokers; if their assets go down then they will get margin calls from brokers and will have to sell assets to meet them. The common theme is:

- You buy some assets with other people’s money.

- The assets go down.

- The people — depositors, investors, prime brokers — call you up and say “you used my money to buy assets, and the assets went down, so now I want my money back.”

- They have the right to do that.

- You have to sell assets to pay them back.

- This makes the price of the assets go down more.

- Go to Step 2.

This means, for one thing, that if you run a pension you can confidently invest in risky assets like stocks: If stocks go down one year, you can make it up next year; you’re not going to have to shut down your pension fund because investors withdraw money after a year of bad returns. It also means that pensions are not supposed to destabilize financial markets: They are long-term investors and are not forced to sell when markets go down.

Third, an accounting point. Take the simple model of a pension: You buy a bond today to pay £100 in 30 years. I said above — with some simplification — that you pay about £48 for that bond. That is the value of that bond: The value of getting £100 in 30 years is £48 today. How do you account for that? What does the balance sheet look like? At some conceptual level, the balance sheet looks like “in 30 years I will have pension liabilities of £100 and assets of £100,” so it balances. But in practice accounting doesn’t work that way. In practice you will record the value of the bond as an asset, today, at £48. But by the same logic, you will record the value of your liability at £48: The cost of paying £100 in 30 years is £48 today, so you have assets of £48 and liabilities of £48 and it all balances.

What happens if interest rates change? Let’s say that the interest rate on 30-year gilts falls to 2%. This means that the market value of your bond goes up, to about £55. Do you have a windfall profit? Can you sell a portion of the bond? No, of course not. The market value of your bond has gone up, but you don’t care about that. The bond, for you, is a long-term, hold-to-maturity investment. For you, the bond pays £100 in 30 years; you don’t care about its market price now. But by the same logic, the present value of your liabilities goes up: Your obligation to pay £100 in 30 years is now “worth” £55, using a 2% discount rate. So your balance sheet still balances.

In the simple case, none of this matters and it is sort of a confusing fiction. You have to pay £100 in 30 years, you have an asset that pays £100 in 30 years, you’re done; market fluctuations don’t affect you at all. Accountants will want you to record the value of your asset and the value of your liability at their discounted present value, and that value will fluctuate with market interest rates. As rates go up, the value of your bonds will go down but the discounted cost of future pension benefits will go down; as rates go down, the bonds will go up but your cost will go up too. In the simple case these things will always offset and won’t trouble you very much.

But once you move beyond the simple case this gets worse. Let’s say you have to pay £100 of benefits in 30 years, and you plan to pay for that using half bonds (gilts worth £24 today) and half stocks (stocks worth £5 today). If gilts yield 2.5% and stocks return 8% per year for 30 years, that will give you £100 in 30 years, enough to pay those benefits. But today, you have assets of £29 (£24 of gilts and £5 of stocks), and liabilities of £48 (the present value of that £100 pension obligation in 30 years at a 2.5% discount rate). So your pension is underfunded, by £19. 3 It happens! It might be fine, if you get the returns you want. But it could make you nervous. One way to overcome this nervousness is to invest in even riskier assets with higher returns, so that next year you have, you know, £33, and are less underfunded.

The bigger problem is what happens when interest rates change. Again, say that the interest rate on 30-year gilts falls to 2%. Now you have £55 of liabilities (the present value of your pension obligations discounted at 2%). The value of your gilt holdings has gone up to £27.50 as rates fell. The value of your stock holdings might not have, though; stocks don’t move automatically with interest rates. Still, let’s say that your stocks have gone up, by 20%, to £6. Now you have £55 of liabilities and £33.50 of assets. You are underfunded by £21.50 instead of £19, which is worse. You have “lost money,” in a very accounting-fiction-y sense. Your actual pension obligations (how much you need to pay in 30 years) have stayed the same, and the market value of your assets has gone up. But your accounting statements show that you have lost money.

Notice that what this means is that, on a reasonable set of assumptions, pensions are short gilts: They lose money (in an accounting sense) whenever interest rates go down (and gilt prices rise), and they make money (in an accounting sense) whenever interest rates go up (and gilt prices go down). 4 Notice also how counterintuitive this is: In its simplest form, a pension fund just is a pile of gilts. The basic default move for a pension manager is to take a bunch of money and put it in gilts. Intuitively, she is long gilts: She has a pile of government bonds, and as rates go down the value of her holdings goes up. But as long as she doesn’t put all of it in gilts, and as long as the pension is underfunded, then she is as an accounting matter short gilts.

I said above that pension funds are unusually insensitive to short-term market moves: Nobody in the pension can ask for their money back for 30 years, so if the pension fund has a bad year it won’t face withdrawals and have to dump assets. Still, pension managers are sensitive to accounting. If your job is to manage a pension, you want to go to your bosses at the end of the year and say “this pension is now 5% less underfunded than it was last year.” And if you have to instead say “this pension is now 5% more underfunded than it was last year,” you are sad and maybe fired; if the pension gets too underfunded your regulator will step in. You want to avoid that.

And so the way you will approach your job is something like:

- You will try to beat your benchmark, buying stocks and higher-yielding bonds to try to grow the value of your assets.

- You will hedge the risk of rates going down. If rates go down, your liabilities will rise (faster than your assets); you are short gilts. You want to do something to minimize this risk.

- £24 in gilts,

- £5 in stocks, and

- borrow another £24 and put that in gilts too. 5

This all makes total sense, in its way. But notice that you now have borrowed short-term money to buy volatile financial assets. The thing that was so good about pension funds — their structural long-termism, the fact that you can’t have a run on a pension fund: You’ve ruined that! Now, if interest rates go up (gilts go down), your bank will call you up and say “you used our money to buy assets, and the assets went down, so you need to give us some money back.” And then you have to sell a bunch of your assets — the gilts and stocks that you own — to pay off those margin calls. Through the magic of derivatives you have transformed your safe boring long-term pension fund into a risky leveraged vehicle that could get blown up by market moves.

I know this is bad but I find something aesthetically beautiful about it. If you have a pot of money that is immune to bank runs, over time, modern finance will find a way to make it vulnerable to bank runs. That is an emergent property of modern finance. No one sits down and says “let’s make pension funds vulnerable to bank runs!” Finance, as an abstract entity, just sort of does that on its own.

{continued}

Anyway, as I said above, 30-year UK gilt rates were about 2.5% this summer. They got to nearly 5% this week, and were at about 3.9% at 9 a.m. New York time today. You can fill in the rest. Here are Loukia Gyftopoulou and Greg Ritchie at Bloomberg News:

This is a rule of securities law, though sort of an unwritten one: There is no specific statute banning insider trading, but there is a long tradition of treating it as a form of securities fraud. Using that secret inside information to trade stock is a form of fraud, on someone. (It’s not always clear who: The people on the other side of your trades? The people whose information you misused? Both?)

By analogy, you might assume that using secret inside information to trade anything else is also a form of fraud. We talked about this in June in the context of an insider trading case against a former employee of OpenSea, a marketplace for nonfungible tokens; the employee allegedly knew in advance which NFTs would be advertised on OpenSea’s homepage and bought them so he could flip them at a profit. NFTs are (probably) not securities, so this is not securities fraud, so it’s not classic insider trading. But it’s so much like insider trading that prosecutors charged him with wire fraud anyway. If insider trading securities is securities fraud, then insider trading non-securities is wire fraud.

Anyway it’s not wire fraud but here’s a bourbon insider trading prosecution:

The problem with the first approach is that if you consistently and clearly say “this token is worthless,” probably no one will buy it. (This is not always true — people might buy tokens for a meme, or for aesthetics — but it is a risk.) The problem with the second approach is that if you say “this token represents a bet on the success of our business venture,” then it is probably a security under traditional US securities law, and the US Securities and Exchange Commission will sue you for securities fraud unless (1) you have registered the security or exempted it from registration (you haven’t) and (2) you are telling the truth about your business venture (are you?). The first approach won’t make you any money; the second approach will get you in trouble.

There are various artful ways to split the difference. One rough one is:

I am not saying that that will work, or that it is a good idea, but it is an idea. Here’s an SEC enforcement action from yesterday:

Anyway, as I said above, 30-year UK gilt rates were about 2.5% this summer. They got to nearly 5% this week, and were at about 3.9% at 9 a.m. New York time today. You can fill in the rest. Here are Loukia Gyftopoulou and Greg Ritchie at Bloomberg News:

And here is the Financial Times on the BOE’s intervention:Fund managers running billions for pension funds faced collateral calls on strategies meant to give them exposure to long-dated assets to help match obligations that can extend decades. The so-called liability-driven investment, or LDI, funds were forced to post more collateral after receiving margin calls when gilt prices collapsed.

The central bank stepped in Wednesday after the calls threatened to push the gilt market into a downward spiral. The BOE had been warned by investment banks and fund managers in recent days that the collateral requirements could trigger a gilt crash, according to a person familiar with the BOE’s deliberations before they stepped in.

“The BOE intervention was required to prevent a vicious cycle becoming even more dangerous for pension funds forced to sell their gilt exposures,” Calum Mackenzie, an investment partner at Aon, said after the BOE intervention. “The market’s swift and significant reaction underlined the big risk faced by pension funds who have had or who could have had their liability hedges reduced.”

Firms including BlackRock Inc., Legal & General Group Plc and Schroders Plc manage LDI funds on behalf of pension clients. The pension firms use them to match their liabilities with their assets, often using derivatives.

The size of the LDI market has exploded over the past decade. The amount of liabilities held by UK pension funds that have been hedged with LDI strategies has tripled in size to £1.5 trillion in the 10 years through 2020, according to the Investment Association. These trades are typically used by defined benefit pension schemes. ...

When yields fall the funds receive margin and when yields rise they typically have to post more collateral. After the spike in gilt yields on Friday and into this week, LDI fund managers were hit by margin calls from their investment banks.

LDI collateral buffers are partly set using historical data to build models based on the likely probability of gilt price movements, according to Shalin Bhagwan, head of pension advisory at DWS Group. The sudden recent surge in gilt yields “blew through the models and the collateral buffers,” he said.

And FT Alphaville has two very good explainers of the LDI problem, one by Toby Nangle and another by Alex Scaggs and Louis Ashworth, which I have drawn on here. And here is Nangle’s prescient LDI explainer from July. Modern finance made UK pensions vulnerable to runs, and then there was a run on those pensions, and the Bank of England had to step in to buy gilts to save them, because that’s what happens in a bank run.The bank stressed that it was not seeking to lower long-term government borrowing costs. Instead it wanted to buy time to prevent a vicious circle in which pension funds have to sell gilts immediately to meet demands for cash from their creditors. That process had put pension funds at risk of insolvency, because the mass sell-offs pushed down further the price of gilts held by funds as assets, requiring them to stump up even more cash. “At some point this morning I was worried this was the beginning of the end,” said a senior London-based banker, adding that at one point on Wednesday morning there were no buyers of long-dated UK gilts. “It was not quite a Lehman moment. But it got close.” …

“If there was no intervention today, gilt yields could have gone up to 7-8 per cent from 4.5 per cent this morning and in that situation around 90 per cent of UK pension funds would have run out of collateral,” said Kerrin Rosenberg, Cardano Investment chief executive. “They would have been wiped out.”

Bourbon insider trading

The basic rule in the US is that if you learn some secret information about a stock, and you have an obligation to keep it secret, and you use that information to trade the stock, or you sell that information to someone else so that they can trade the stock, then you have committed insider trading and you get in trouble. 6 The classic case is that you work at a public company and find out something about the company (good or bad earnings, a merger) before it is public and trade on that, but there are other cases. If you work at the company’s law firm, or if you’re the chief executive officer’s psychotherapist, or a regulator, you can learn things and be obligated to keep them secret. And if you trade on them instead you get in trouble.This is a rule of securities law, though sort of an unwritten one: There is no specific statute banning insider trading, but there is a long tradition of treating it as a form of securities fraud. Using that secret inside information to trade stock is a form of fraud, on someone. (It’s not always clear who: The people on the other side of your trades? The people whose information you misused? Both?)

By analogy, you might assume that using secret inside information to trade anything else is also a form of fraud. We talked about this in June in the context of an insider trading case against a former employee of OpenSea, a marketplace for nonfungible tokens; the employee allegedly knew in advance which NFTs would be advertised on OpenSea’s homepage and bought them so he could flip them at a profit. NFTs are (probably) not securities, so this is not securities fraud, so it’s not classic insider trading. But it’s so much like insider trading that prosecutors charged him with wire fraud anyway. If insider trading securities is securities fraud, then insider trading non-securities is wire fraud.

Anyway it’s not wire fraud but here’s a bourbon insider trading prosecution:

In an unusual criminal case unfolding outside Richmond, a former employee of the state’s Alcoholic Beverage Control Authority (ABC) has admitted to working with [Rob] Adams to sell distribution information that would allow bourbon fans to scoop up the limited supply of choice bottles.

Adams, 45, has been charged with embezzlement and other felonies. … The investigation concluded Adams learned that Garcia was an employee at the ABC, Stock said. As a retail specialist making $16.53 an hour, Stock said, Garcia had access to the internal list guiding the distribution of Angel’s Envy Cask Strength, Old Fitzgerald 17-year Bottled in Bond, WhistlePig 18-year Double Malt Rye and other sought-after bottles.

Yeah I mean in securities law this stuff is all reasonably settled, and lots of people go to jail for insider trading without themselves being insiders; paying an insider $600 for inside information more than qualifies. But in state-law bourbon embezzlement cases it is perhaps less clear.“They said, ‘Why don’t we make a little money on the side,’ ” Stock alleged in an interview.

Stock said during Monday’s hearing that Adams paid Garcia $600 for access to the list and promised him bottles of alcohol. …

Vaughan Jones, an attorney for Adams, said his client did distribute the list, but did not commit a crime because he had no legal obligation to keep the information secret.

“My client was never an employee of ABC,” Jones said. “He never accessed the information. He was just giving it out.”

Hydrogen

Here is a weird tension in marketing crypto tokens. If you run some crypto-y project, and it issues a token, and the token is not actually useful for doing anything on your crypto-y platform, one thing that you can do is go around saying “this token has no cash value and will not appreciate, this is for pure entertainment purposes only.” Another thing you can do is go around saying “this token is going to be hugely valuable as our crypto project takes off, buy it now and it will go up.”The problem with the first approach is that if you consistently and clearly say “this token is worthless,” probably no one will buy it. (This is not always true — people might buy tokens for a meme, or for aesthetics — but it is a risk.) The problem with the second approach is that if you say “this token represents a bet on the success of our business venture,” then it is probably a security under traditional US securities law, and the US Securities and Exchange Commission will sue you for securities fraud unless (1) you have registered the security or exempted it from registration (you haven’t) and (2) you are telling the truth about your business venture (are you?). The first approach won’t make you any money; the second approach will get you in trouble.

There are various artful ways to split the difference. One rough one is:

- You consistently say, in boilerplate, “this token has no value and is not an investment.”

- You go around doing podcast interviews where you are like “what a great business we have, we keep making more money, oh there is also a token, how about that.” You don’t say that the token represents a bet on the business, but you vaguely imply it.

- You do a lot of wash trading, where you buy the token from yourself and then sell it back to yourself, at ever-increasing prices, creating the impression that its value is going up.

I am not saying that that will work, or that it is a good idea, but it is an idea. Here’s an SEC enforcement action from yesterday:

The Securities and Exchange Commission today announced charges against The Hydrogen Technology Corporation, its former CEO, Michael Ross Kane, and Tyler Ostern, the CEO of Moonwalkers Trading Limited, a self-described “market making” firm, for their roles in effectuating the unregistered offers and sales of crypto asset securities called “Hydro” and for perpetrating a scheme to manipulate the trading volume and price of those securities, which yielded more than $2 million for Hydrogen.

The SEC’s complaint alleges that starting in January 2018, Kane and Hydrogen, a New York-based financial technology company, created its Hydro token and then publicly distributed the token through various methods: an “airdrop,” which is essentially giving away Hydro to the public; bounty programs, which paid the token to individuals in exchange for promoting it; employee compensation; and direct sales on crypto asset trading platforms. The complaint further alleges that, after distributing the token in those ways, Kane and Hydrogen hired Moonwalkers, a South Africa-based firm, in October 2018, to create the false appearance of robust market activity for Hydro through the use of its customized trading software or “bot” and then selling Hydro into that artificially inflated market for profit on Hydrogen’s behalf. Hydrogen allegedly reaped profits of more than $2 million as a result of the defendants’ conduct.

{continued}

They gave the tokens away for free (including to themselves), and were careful-ish about not advertising them as an investment. From the SEC complaint:

This didn’t really work, I don’t think, in that the SEC brought the case, but I want to highlight the thought process. If (1) the token is absolutely valueless and has nothing to do with any operating business, and (2) you say that clearly and consistently, then you have a decent argument that it is not a “security.” The “Howey test” of securities law says that something is a security if it involves “the investment of money in a common enterprise with a reasonable expectation of profits to be derived from the efforts of others,” and if you consistently say “there’s no enterprise, there’ll be no profits, and we’ll make no efforts” then you can argue that your token is not a security.

If you then also hire someone to do a bunch of spoofing and wash trading in your token, that’s bad, and somebody (the Commodity Futures Trading Commission? prosecutors?) might go after you for fraud, but the SEC won’t go after you for securities fraud because the fraud that you are doing is not to a security. If your model is that the SEC has way less of a sense of humor about these things than anyone else, then that might be a good outcome.

If you thought that Luna was an investment in the collaborative effort to build the value of the Terra blockchain, then (1) it’s a security 7 and (2) maybe you wanted to buy it, which is why Luna had a market capitalization in the tens of billions of dollars. If you thought that Luna was just, like, an electronic token with no investment thesis, then maybe it wasn’t a security — but why were you buying it?

If you'd like to get Money Stuff in handy email form, right in your inbox, please subscribe at this link. Or you can subscribe to Money Stuff and other great Bloomberg newsletters here. Thanks!

They gave the tokens away for free (including to themselves), and were careful-ish about not advertising them as an investment. From the SEC complaint:

But instead they allegedly created that impression through trading:Hydrogen and Kane publicly marketed Hydro as a so-called “utility” token on the company’s website and its social media pages and channels, initially claiming that it would function as an “API key” within Hydrogen’s existing non-blockchain API business. However, at no point during the Relevant Period, including during the offers and sales of Hydro, could the token be used within Hydrogen’s existing non-blockchain API. ...

While Hydrogen and Kane worked to have Hydro listed on crypto asset trading platforms, the company fielded numerous questions on its social media pages and channels from Hydro recipients and purchasers about the token’s value and whether and when Hydrogen expected the token’s price to increase.

At Kane’s direction, Hydrogen created a set of scripted responses to these questions, being careful not to expressly state that the Hydro token would increase in value.

“The name ‘Moonwalkers,’” explains the SEC, “derives from the expression ‘going to the moon,’ which is used by crypto enthusiasts and issuers to describe the potential significant appreciation in price or value of crypto assets,” terrific. You walk a token to the moon with fake trading I guess.Kane began selling the company’s Hydro through crypto asset trading platforms in May 2018, but soon after learned that selling a significant volume of Hydro would depress the token’s price and hinder his efforts to raise much-needed capital for Hydrogen. As a result, in October 2018, Kane privately hired and directed Ostern and his company, Moonwalkers, a self-described crypto asset “market maker,” to manipulate Hydro’s trading price and volume so that the company’s Hydro sales would be more profitable. Moonwalkers did so by creating the false appearance of robust Hydro trading and artificially propping up the token’s price.

Specifically, at Kane’s direction, Ostern used a customized trading bot (a computer program that automates trades) to sell the company’s Hydro through Kane’s personal trading accounts on crypto asset trading platforms. Among other manipulation tactics, Ostern placed and canceled both buy and sell orders at random increments to artificially inflate the Hydro token’s trade volume and price, thereby enabling sales of the company’s Hydro to be more profitable.

Ostern provided Kane and Hydrogen with regular updates on his market manipulation efforts. For example, on October 11, 2018, just days after the Hydro market manipulation began, Ostern told Kane that he was “starting off slow, trying to keep the sell pressure minimal until [he could] build enough capital to really get the market moving upward” and indicated that they would “have plenty of excuses to pump price and sell into the FOMO [fear of missing out] guys down the road.” Two weeks later, Ostern told Kane about his “volume shenanigans” on a popular, high-volume crypto asset trading platform, and bragged that it had taken his bot “about 3 seconds” to generate the illusion that “a million” Hydro tokens had been bought and sold—“[a]round half” of which Ostern admitted was “fake.”

This didn’t really work, I don’t think, in that the SEC brought the case, but I want to highlight the thought process. If (1) the token is absolutely valueless and has nothing to do with any operating business, and (2) you say that clearly and consistently, then you have a decent argument that it is not a “security.” The “Howey test” of securities law says that something is a security if it involves “the investment of money in a common enterprise with a reasonable expectation of profits to be derived from the efforts of others,” and if you consistently say “there’s no enterprise, there’ll be no profits, and we’ll make no efforts” then you can argue that your token is not a security.

If you then also hire someone to do a bunch of spoofing and wash trading in your token, that’s bad, and somebody (the Commodity Futures Trading Commission? prosecutors?) might go after you for fraud, but the SEC won’t go after you for securities fraud because the fraud that you are doing is not to a security. If your model is that the SEC has way less of a sense of humor about these things than anyone else, then that might be a good outcome.

Do Kwon

In entirely related news, let’s check in with Do Kwon, the founder of the blown-up Terra blockchain and its token Luna, in an undisclosed location:Mr. Kwon faces charges of violating South Korea’s capital market law, according to the country’s Yonhap News Agency. But Terraform Labs argued that the law would only apply to Luna if it were a security. If it isn’t a security, then Mr. Kwon and his firm didn’t do anything illegal, the Terraform Labs spokesman said.

Terraform Labs’ argument that Luna isn’t a security stems from the murky regulatory status of cryptocurrencies, which many countries around the world have struggled with, including the United States. Officials, such as Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, have cited the collapse of TerraUSD as evidence for the need for stronger crypto regulation.

The Terraform Labs spokesman suggested that South Korean prosecutors had expanded the definition of a security in response to public pressure over the collapse of Luna, which has since been renamed “Luna Classic” as Mr. Kwon has sought to launch a new version of the cryptocurrency.

“We believe, as do most in industry, that Luna Classic is not, and has never been, a security, despite any changes in interpretation that Korean financial officials may have recently adopted,” Terraform Labs’ spokesman said.

If you thought that Luna was an investment in the collaborative effort to build the value of the Terra blockchain, then (1) it’s a security 7 and (2) maybe you wanted to buy it, which is why Luna had a market capitalization in the tens of billions of dollars. If you thought that Luna was just, like, an electronic token with no investment thesis, then maybe it wasn’t a security — but why were you buying it?

Things happen

The Unstoppable Dollar Is Wreaking Havoc Everywhere But America. US Mortgage Rates Jump to 6.7%, Hitting Highest Level Since 2007. VW Prices Porsche IPO at Top of Range. People are worried about bond market liquidity. Nikola Founder Bought Utah Ranch With ‘Worthless’ Stock Options. Crazy Eddie’s nephew sued an online casino for glitches. LeBron James Is Buying a Professional Pickleball Team.If you'd like to get Money Stuff in handy email form, right in your inbox, please subscribe at this link. Or you can subscribe to Money Stuff and other great Bloomberg newsletters here. Thanks!

- In real life you need to pay out a bunch of money at many different points in the future, and those government bonds pay interest between now and 30 years from now, and you have some actuarial risk about how long your beneficiaries will live, etc. You’ll buy lots of bonds maturing at lots of points, and reinvest interest, and have some uncertainty about your liabilities. And I am entirely ignoring the effects of inflation, inflation-indexing of benefits, inflation-linked bonds, etc. But simplifying it as “you have to pay a bunch of money in 30 years, so buy assets that will provide that amount of money in 30 years” is fine.

- This is just the price of a zero-coupon 30-year bond at a 2.5% yield paying £100 at maturity, i.e. =PV(.025,30,0,-100) in Excel. There are some embedded assumptions there and don’t take it too seriously, but in fact a UK gilt principal strip maturing in 2049 (UKTR 0 12/07/49 Govt on Bloomberg) was trading in the sort of 45-51 area this June and July so good enough.

- I’m assuming for simplicity that you discount your liabilities at the risk-free rate, which is not really right, but directionally this is all pretty much true even if you use some spread to the risk-free rate.

- The basic driver of this in my simplified math is the underfunding. If you have a pension with £29 of assets and £48 of liabilities, and discount rates go down, then the values of your assets and liabilities both increase; even if they increase by the same proportion (even if the assets increase by *more*, proportionally), the liabilities are bigger so your underfunding gets larger.

- No science to this number, and you’d probably do a bit less if your stocks are correlated with rates.

- There are tons of nuances to this rule — I say “stock” but also mean bonds and options; if you give the information to someone else, instead of selling it, you might or might not also be in trouble — and none of this is legal advice, but this is the basic rule.

- I’m being loose here — I have been talking about US law, and this is an issue of South Korean law. Nonetheless the basic idea of “is this an investment in a business (a security) or a collectible curiosity (not a security)?” seems conceptually relevant no matter the details of the legal regime.

This is what the people voted for though, oh well.Boris and rishi left the uk in shambles

Can I get a TLDR?

Bank of England expects UK to fall into longest ever recession

The Bank of England raises interest rates to 3%, marking the biggest rise for 33 years.

www.bbc.com

Bank of England expects UK to fall into longest ever recession

- 1 hour ago

- comments

Comments

Business reporter, BBC News

The Bank of England has warned the UK is facing its longest recession since records began, as it raised interest rates by the most in 33 years.

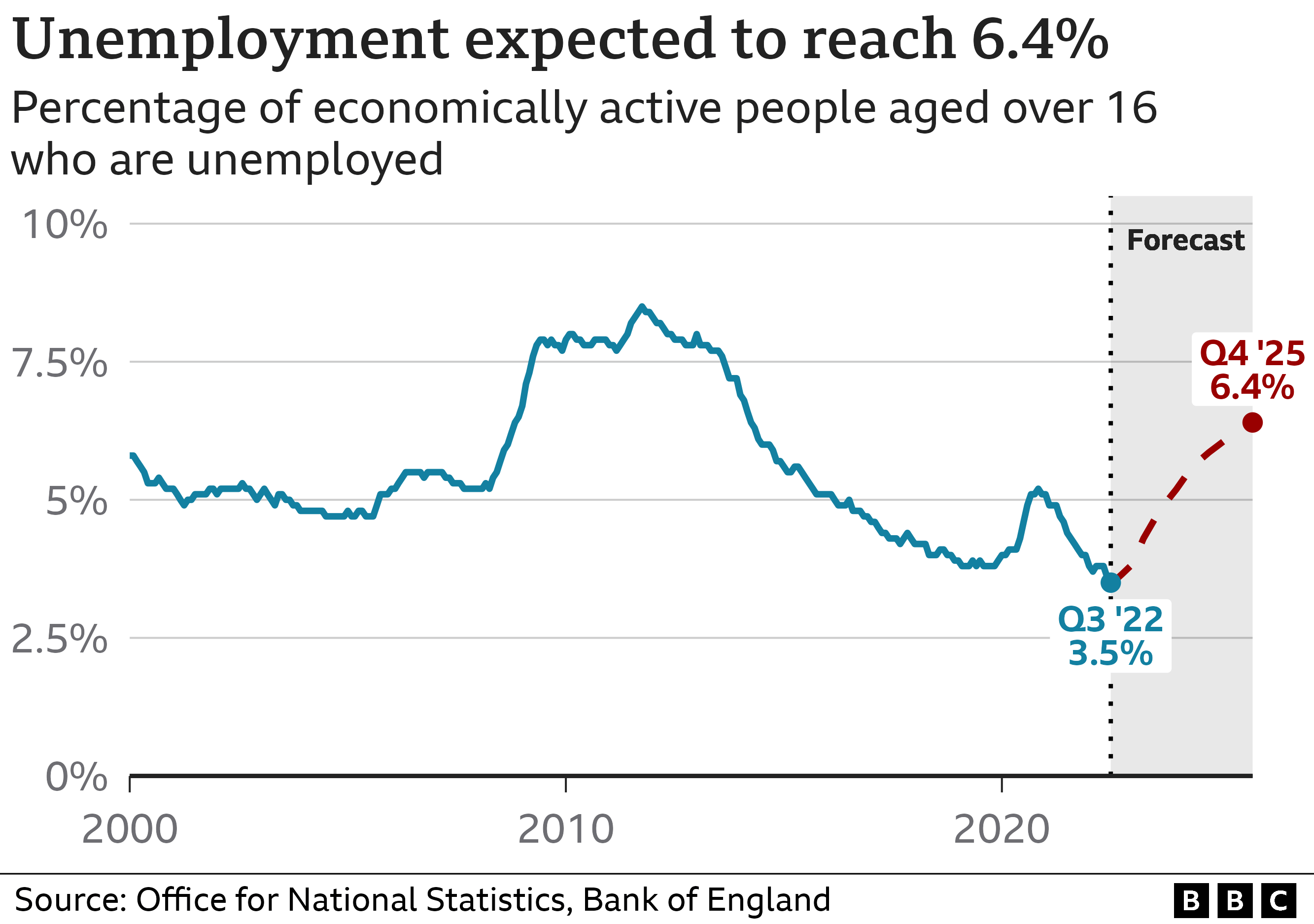

It warned the UK would face a "very challenging" two-year slump with unemployment nearly doubling by 2025.

Bank boss Andrew Bailey warned of a "tough road ahead" for UK households, but said it had to act forcefully now or things "will be worse later on".

It lifted interest rates to 3% from 2.25%, the biggest jump since 1989.

By raising rates, the Bank is trying to bring down soaring prices as the cost of living rises at its fastest rate in 40 years.

Food and energy prices have jumped, in part because of the Ukraine war, which has left many households facing hardship and started to drag on the economy.

A recession is defined as when a country's economy shrinks for two three-month periods - or quarters - in a row.

Typically, companies make less money, pay falls and unemployment rises. This means the government receives less money in tax to use on public services such as health and education.

The Bank had previously expected the UK to fall into recession at the end of this year and said it would last for all next year.

But it now believes the economy already entered a "challenging" downturn this summer, which will continue next year and into the first half of 2024 - a possible general election year.

While it will not be the UK's deepest downturn, it will be the longest since records began in the 1920s, the Bank said.

The unemployment rate is currently at its lowest for 50 years, but it is expected to rise to nearly 6.5%.

The interest rate announcement is the first since former Prime Minister Liz Truss and former Chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng unveiled their controversial mini-Budget in September.

Their plans for £45bn worth of unfunded tax cuts - much of which have been reversed - sent the value of the pound tumbling and sparked market turmoil, forcing the Bank of England to step in to restore calm.

Mr Bailey told the BBC he believed that the mini-budget had "damaged" the UK's standing internationally.

He said that at a recent International Monetary Fund gathering in Washington "it was very apparent to me that the UK's position and the UK's standing had been damaged".

That same week, Mr Kwarteng was sacked as Chancellor.

Chancellor Jeremy Hunt said: "The most important thing the British government can do right now is to restore stability, sort out our public finances, and get debt falling so that interest rate rises are kept as low as possible."

But shadow chancellor Rachel Reeves said families could not withstand such high rate rises "when we've got rising food prices, rising energy bills and now higher mortgage rates as well".

The latest rate hike - the Bank's eighth since December - takes borrowing costs to their highest since 2008, when the UK banking system faced collapse.

The Bank believes by raising interest rates it will make it more expensive to borrow and encourage people not to spend money, easing the pressure on prices in the process.

But while its latest rate rise will be welcomed by savers, it will have a knock-on effect on those with mortgages, credit card debt and bank loans.

'I'm nervous about the loan on my van'

"My disposable income has gone down dramatically recently and I earn more than the amount to get benefits," she told the BBC. "They need to help the middle earners."

Michelle needs the van to get to work as there's no public transport near her. But if her loan repayment costs rise she fears she'll have to give up the vehicle.

"I can work from home, but like most places my place of work wants us back in the office at least three days a week and I've had to have talks with them about how I can afford that.

"It's a 60-mile round trip, it's expensive."

Those with mortgages are also feeling nervous. The Bank forecasts that if interest rates continue to rise, those whose fixed rate deals are coming to an end could see their annual payments soar by up to £3,000.

It said that it would increase interest rates if inflation remained high. Financial markets had been expecting rates to peak at 5.25% but the Bank does not expect them to rise this high.

The Bank's rate decision comes before the government unveils its tax and spending plans under new Prime Minister Rishi Sunak at the Autumn Statement on 17 November.

On Thursday, the pound slumped 2% against the dollar and the cost of government borrowing rose in response to the Bank's warnings.

Funny the whole Western world was shytty on us raising interest rates now everybody want to be on the same wave

Something interesting I noticed too. The Federal rate is way lower than it was in 2008 yet mortgage rates are at an all time high. In other words banks are pocketing the difference and blaming the government.

Just another form of greedflation

Something interesting I noticed too. The Federal rate is way lower than it was in 2008 yet mortgage rates are at an all time high. In other words banks are pocketing the difference and blaming the government.

Just another form of greedflation

Pension funds hold investments for retirees. This bank borrowed money to invest (normal) and used some of their assets as collateral on a larger loan of some kind. When a brokerage starts seeing you as a bad investment, they'll margin call you (sell off all your stocks, etc. that you used as collateral to recoup some of their losses). Kind of a soft bankruptcy.Can I get a TLDR?

Basically the first sign of what AMC and GME stock holders were waiting for. It's evidence that companies betting on AMC and GME to go bankrupt are finally being forced to pay the piper.