Turkey referendum: Erdogan camp set to win after most votes counted

- 16 April 2017

- Europe

The referendum has divided Turkey - a country facing no shortage of problems

Turks have voted to grant President Recep Tayyip Erdogan sweeping new powers in a referendum, partial official results indicate.

With more than four-fifths of ballots counted, "Yes" was on about 54% and "No" on about 46%.

Erdogan supporters say replacing the parliamentary system with an executive presidency would modernise the country.

Opponents have attacked a decision to accept unstamped ballot papers as valid unless proven otherwise.

A "Yes" vote could also see Mr Erdogan remain in office until 2029.

Three people were shot dead near a polling station in the south-eastern province of Diyarbakir, reportedly during a dispute over how they were voting.

About 55 million people were eligible to vote across 167,000 polling stations, and turnout is said to have been high.

How significant are the changes?

They would represent the most sweeping programme of constitutional changes since Turkey became a republic almost a century ago.

Mr Erdogan would be given vastly enhanced powers to appoint cabinet ministers, issue decrees, choose senior judges and dissolve parliament.

The new system would scrap the role of prime minister and concentrate power in the hands of the president, placing all state bureaucracy under his control.

What is the case for 'Yes'?

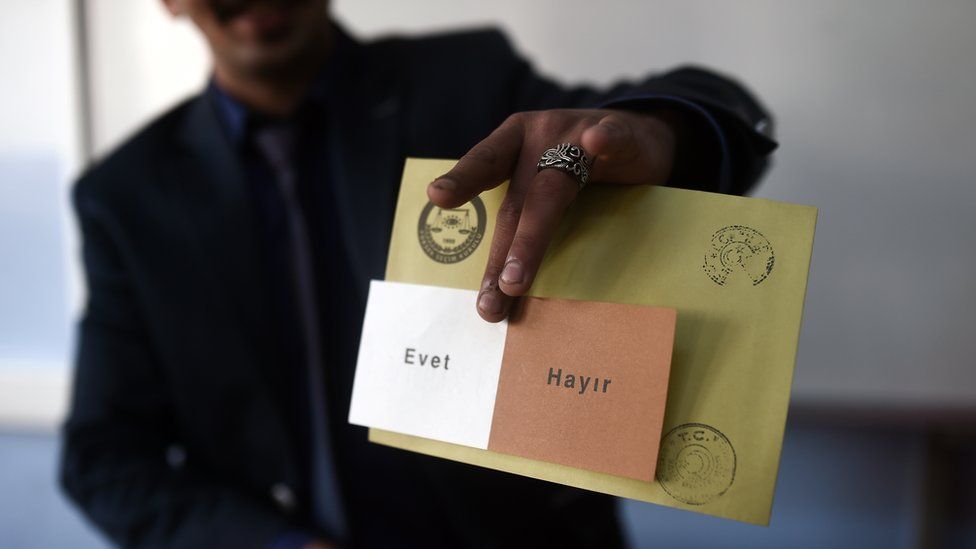

There is just a simple "Yes" or "No" choice on the ballot

Mr Erdogan says the changes are needed to address Turkey's security challenges nine months after an attempted coup, and to avoid the fragile coalition governments of the past.

"This public vote is [about] a new governing system in Turkey, a choice about change and transition," he said after casting his vote in Istanbul.

The new system, he argues, will resemble those in France and the US and will bring calm in a time of turmoil marked by a Kurdish insurgency, Islamist militancy and conflict in neighbouring Syria, which has led to a huge refugee influx.

Mr Erdogan voted in Istanbul accompanied by his wife and two grandchildren

The referendum, the BBC's Mark Lowen reports, is effectively one on Mr Erdogan and the Turkey he has moulded in his image: fiercely nationalist and conservative.

And what about for 'No'?

Critics of the proposed changes fear the move would make the president's position too powerful, arguing that it would amount to one-man rule, without the checks and balances of other presidential systems.

Turkish academic Oget Oktem Tanor, 82, voices her fears for her country

They say his ability to retain ties to a political party - Mr Erdogan could resume leadership of the AK Party (AKP) he co-founded - would end any chance of impartiality.

Kemal Kilicdaroglu, leader of the main opposition Republican People's Party (CHP), told a rally in Ankara a "Yes" vote would endanger the country.

Supporters greeted main opposition leader Kemal Kilicdaroglu when he voted in Ankara

"We will put 80 million people... on a bus with no brakes," he said.

"No" supporters have complained of intimidation during the referendum campaign and that Turkey's highly regulated media has given them little coverage.

A country of two halves: Mark Lowen, BBC News, Ankara

A divisive campaign has ended and Turkey now faces the biggest political choice in its modern history.

I watched as queues of voters turned up to a polling station in Ankara where the voting process was quick and efficient. After two identity checks, they were handed the ballot paper. Behind the curtain they stamp their chosen side - "Yes" or "No" - determining the future of this crucial and deeply troubled country.

Peering down above the ballot box was a picture of the Republic's founding father, Kemal Ataturk. If the constitutional reform is accepted, President Erdogan could eclipse even his power.

One voter told me a "Yes" would lead Turkey into dictatorship - and that for his grandchildren's future he had voted "No". Another said he had backed "Yes" for a stronger republic and that "the outside world is against Turkey".

Turkey's polarisation runs deep. And whichever way this goes, one half of the country will feel defeated.

Critics abroad fear Erdogan's reach

The day a Turkish writer's life changed

What's the wider context?

Many Turks already fear growing authoritarianism in their country, where tens of thousands of people have been arrested, and at least 100,000 sacked or suspended from their jobs, since a coup attempt last July.

The campaign unfolded under a state of emergency imposed in the wake of the failed putsch.

Mr Erdogan assumed the presidency, meant to be a largely ceremonial position, in 2014 after more than a decade as prime minister.

Women in Istanbul campaigned for the "No" vote on Thursday

This once stable corner of the region has in recent years been convulsed by terror attacks and millions of refugees, mostly from Syria, have arrived.

At the same time, the middle class has ballooned and infrastructure has been modernised. Under Mr Erdogan, religious Turks have been empowered.

Relations with the EU, meanwhile, have deteriorated. Mr Erdogan sparred bitterly with European governments who banned rallies by his ministers in their countries during the referendum campaign. He called the bans "Nazi acts".

In one of his final rallies, he said a strong "Yes" vote would "be a lesson to the West".

Turkey's dominant president

The ultranationalists who could sway Erdogan

What's in the new constitution?

The draft states that the next presidential and parliamentary elections will be held on 3 November 2019.

The president would have a five-year tenure, for a maximum of two terms.

- The president would be able to directly appoint top public officials, including ministers

- He would also be able to assign one or several vice-presidents

- The job of prime minister, currently held by Binali Yildirim, would be scrapped

- The president would have power to intervene in the judiciary, which Mr Erdogan has accused of being influenced by Fethullah Gulen, the Pennsylvania-based preacher he blames for the failed coup in July

- The president would decide whether or not impose a state of emergency