You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The Red Summer of 1919-The Race War you Never knew about...

- Thread starter cole phelps

- Start date

More options

Who Replied?TRAP AMERICAN TV

TRAP GOLD

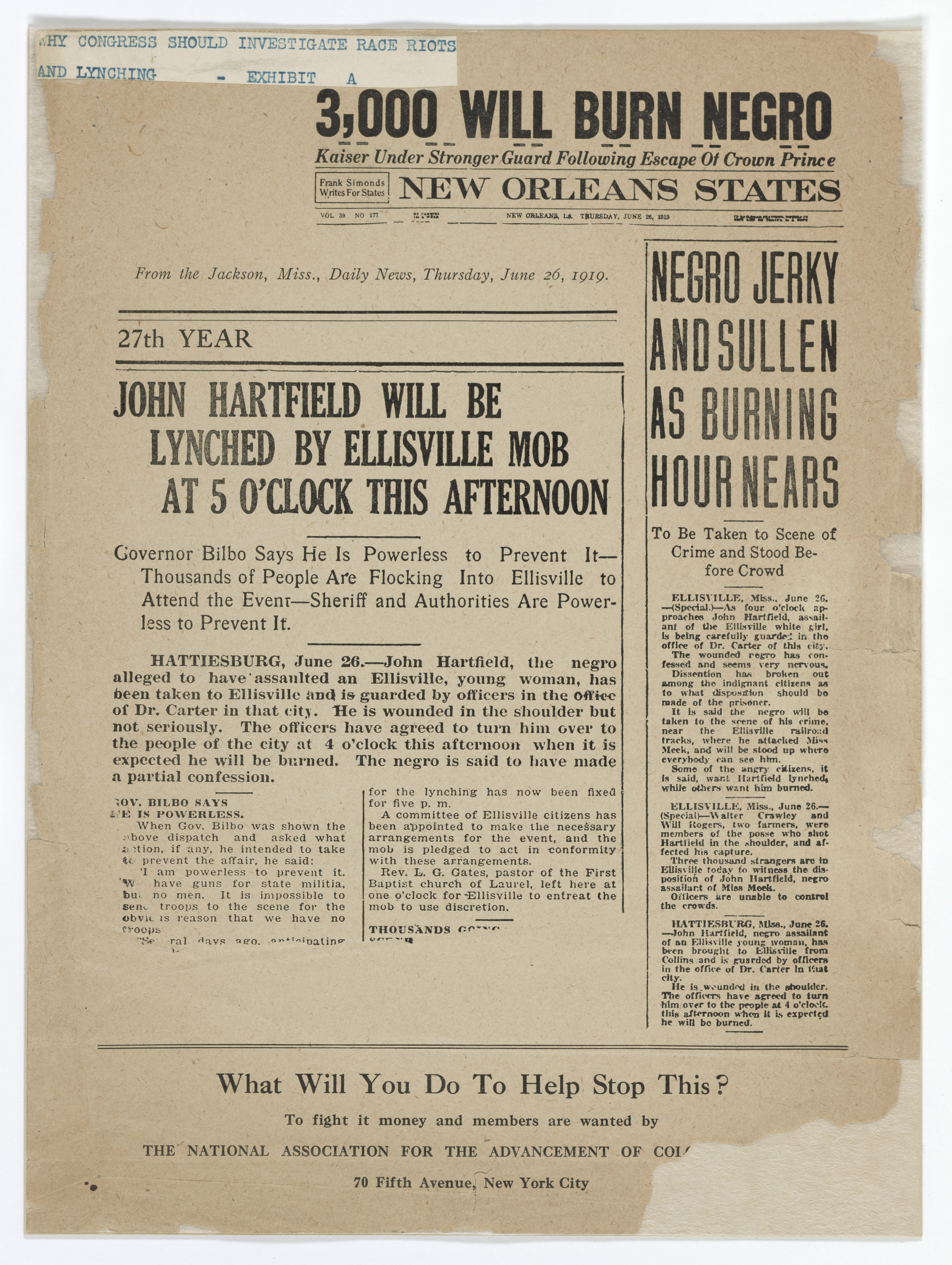

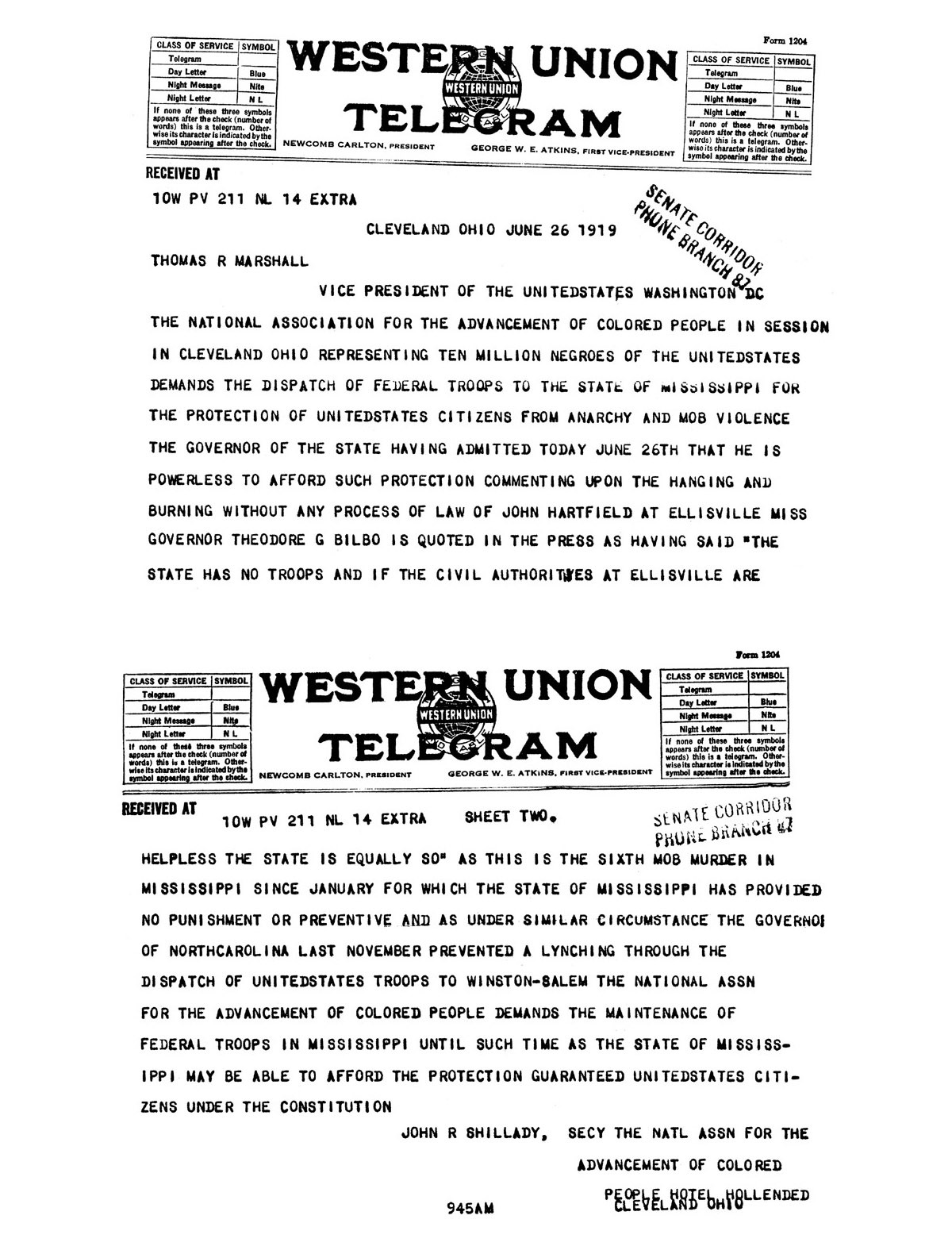

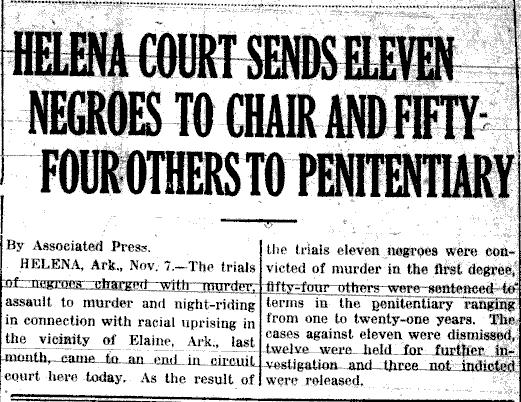

Did anybody do a movie on this?Following the violence-filled summer, in the autumn of 1919, Haynes reported on the events. His report was to be the brief for an investigation of the issues by the U.S. Senate Committee on the Judiciary. He identified 38 separate riots in widely scattered cities, in which whites attacked blacks .[1] In addition, Haynes reported that between January 1 and September 14, 1919, white mobs lynched at least forty-three African Americans, with sixteen hanged and others shot; while another eight men were burned at the stake. The states appeared powerless or unwilling to interfere or prosecute such mob murders.[1] Unlike earlier race riots in U.S. history, the 1919 events were among the first in which blacks in number resisted white attacks. A. Philip Randolph, a civil rights activist and leader of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, defended the right of blacks to self-defense.[2]

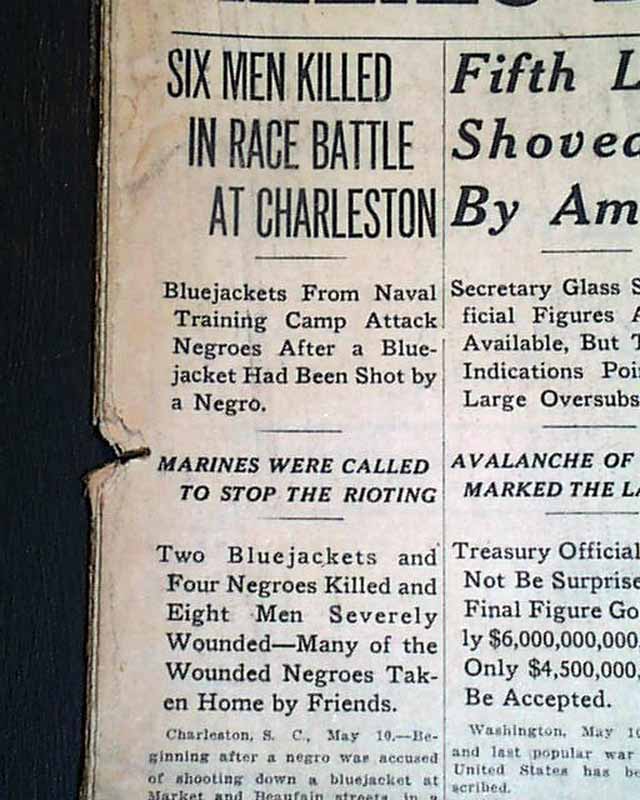

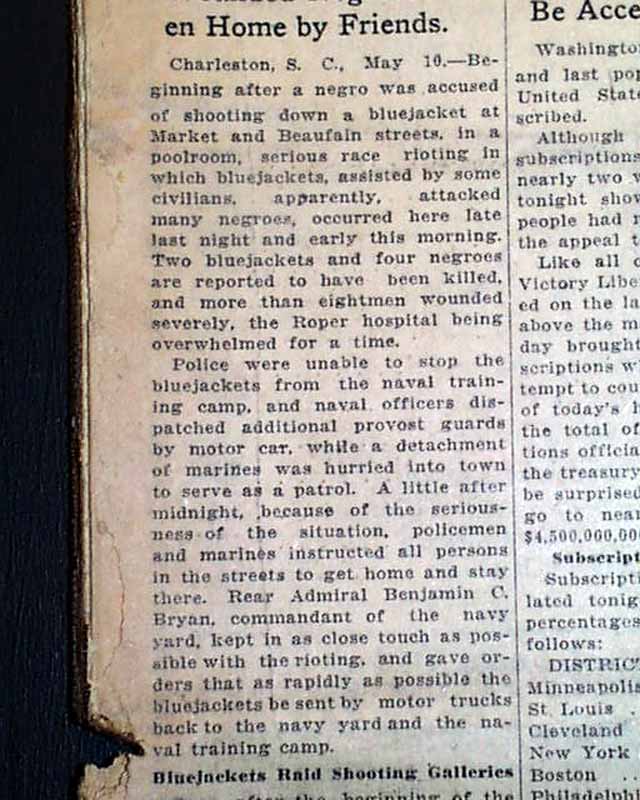

In the words of the Navy investigation, “a disturbance which assumed the nature and proportions of a race riot took place in the city of Charleston, South Carolina, on the night of May 10-11, 1919, between the hours of 7:00 p.m., and 3:00 a.m.” Charleston in 1920 numbered 80,000 people, more than half of whom were black. On one side of the conflict were black civilians, and on the other was “a mixed crowd of whites” including mostly sailors, along with civilians, and “a scattering of soldiers and marines.” The incident started when an unidentified black man allegedly pushed Roscoe Coleman, U.S. Navy, off the sidewalk. A group of sailors and civilians chased the man, who took refuge in a house on St. Philip Street.

A fight then took place there, with both sides throwing bricks, bottles, and stones. The crowd dispersed when one of the black civilians “drew a revolver and fired four shots without injuring anyone.” There followed “wild rumors and stories of a sailor having been shot by a negro” and general rioting. Beginning near Harry Polices’ Poolroom at the corner of Charles and Market streets, rioting spread to other parts of the city and continued with varying intensity until about 3:00 a.m. Charleston’s Mayor Hyde requested assistance in restoring order. The Charleston

Navy Yard sent a detachment of soldiers and marines to help.“Bluejackets” were rounded up by the Marines and either taken back to the Navy Yard or held at the police station. All blacks were told to get off the streets.

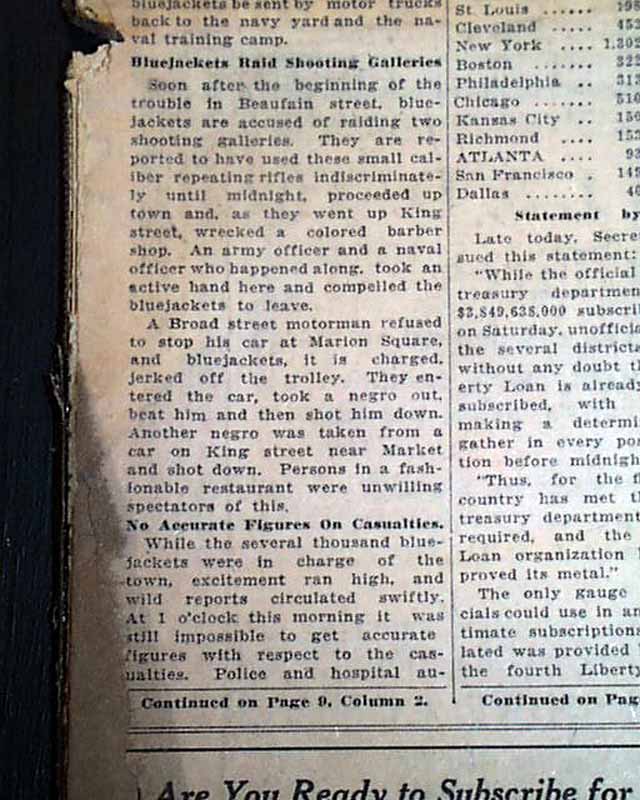

During the riot, both sides used firearms. Sailors stole thirteen 22-calibre rifles from the shooting galleries of H.B. Morris and Fred M. Faress. Rioters robbed and vandalized W. G. Fridie’s barber shop at 305 King Street and James Freyer’s shoe shop, both black-owned businesses. Eighteen black men were seriously injured, as were five white men. Three black men, William Brown, Isaac Doctor, and James Talbot, died of gunshot wounds.

The Navy report sets out the final analysis. The riot was “of spontaneous origin and was precipitated by the actions of certain negroes, sailors, and at least one white civilian. . . [A]n active part in this initial disturbance was taken by the following men: G.W. Biggs, Coppersmith, second class, U.S. Navy, USS Hartford; Roscoe Coleman, Fireman third class, U.S. Navy, Machinist Mates School; Robert Morton, Fireman, third class, U.S. Navy, Machinist Mates School, and Alexander Lanneau, white civilian, a resident of Charleston, South Carolina, who . . . was responsible for stirring up strife and inciting others to violence against the negroes. . . . Ralph Stone, Fireman, third class, U.S. Navy, Machinist Mates School, was one of the leaders and inciters of a mob. . . . [T]he wound in the right chest of Isaac Doctor . . . was inflicted by a 22-calibre bullet fired from a rifle in the hands of either Jacob Cohen, Fireman, third class, U.S. Navy, or George T. Holliday, Fireman, third class, U.S. Navy, who are jointly responsible for his death. . . [A]ll property damage, . . except in the case of Harry Police’s poolroom where damage was caused by negroes, was caused by the unlawful actions of mobs, which in all cases were composed principally of sailors. . . [A]ll injuries to negro men. . . were inflicted by mobs composed prinicipally of sailors.”

The Charleston rioting demonstrates a typical characteristic of white mob violence in the United States. Despite a thorough, dispassionate investigation, despite evidence and the naming of culpable individuals, and despite it being well within the purview of the military authorities to do so, very little punishment was exacted. Cohen and Holliday, although the Navy report held them responsible for the death of Isaac Doctor, were eventually sentenced for their involvement in the riot to only a year in Parris Island, South Carolina.

cole phelps

Superstar

nopeDid anybody do a movie on this?

cole phelps

Superstar

cole phelps

Superstar

Knicksman20

Superstar

richaveli83

Veteran

No offense but I hate this thread

cole phelps

Superstar

bump

Knicksman20

Superstar

This thread is a tough read but necessary to educate yourself

cole phelps

Superstar

Crayola Coyote

Superstar

Disagree. Even though racism never left the white folks now are no way compared to the devils back then.

I seriously believe though they need to study white folks for hatred to the other man because they are not normal brehs the Shyt they have done doesn't make any sense and I am going back centuries. The hatred is so inbred I wouldn't be surprise if it is in their DNA.

Lady talking about "post traumatic slave disorder" said that when you start doing bad shyt to people for 5 centuries it takes a toll on your mind. White ppl are clinically fukked up

DynamoEAR

All Star

Bump.

Swap Fox News, CNN, MSNBC for the dude sowing seeds with that bullshyt "both sides" rhetoric for the first cartoon, and preachers, politicians, and general 21st century bougie negroids for the second cartoon and my God, the arguments haven't changed one bit.

Things are better if you consider cacs not lynching us in public in cold blood as progress. The same mental deflections that do anything to not accept black people as human beings still exists roughly 100 years later.