Clinton Emails Reveal “Behind the Doors Actions” of Private Sector and US Embassy in Haiti Elections

Recently

released e-mails from Hillary Clinton’s private server reveal new details of how U.S. officials worked closely with the Haitian private sector as they forced Haitian authorities to change the results of the first round presidential elections in late 2010. The e-mails documenting these “behind the doors actions” were made public as part of an ongoing Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) lawsuit.

Preliminary results from the deeply flawed 2010 presidential and legislative elections were announced on December 7, 2010, showing René Préval’s hand-picked successor Jude Célestin and university professor Mirlande Manigat advancing to a second-round runoff. The same day, the U.S. Embassy in Haiti

released a statement questioning the legitimacy of the announced results.

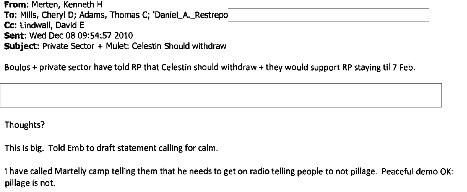

Behind the scenes, key actors were already pushing for Célestin to withdraw from the race, according to the e-mails. Just a day after preliminary results were announced, U.S. Ambassador to Haiti Kenneth Merten wrote to Cheryl Mills, Tom Adams and Daniel Restrepo, all key State Department Haiti staff. “Boulos + private sector have told RP [René Préval] that Célestin should withdraw + they would support RP staying til 7 Feb.” “This is big,” the ambassador added.

Boulos” here refers to Reginald Boulos, one of the largest industrialists in Haiti and a member of the Private Sector Economic Forum. Importantly, Boulos also suggested they would support Préval staying in office through February 7, but with the election delayed due to the earthquake, a new president would not be able to take office by then. Many had advocated for Préval’s early departure, and during a meeting of international officials on election day, Préval was

even threatened with being forced out of the country.

The e-mail also shows that Merten was in close contact with Michel Martelly’s campaign. Protests had

already broken out across Port-au-Prince and in other cities throughout Haiti, with protesters alleging that their preferred candidate, Michel Martelly, should be in the runoff. Merten writes that he had personally contacted Martelly’s “camp” and told them that he needs to “get on radio telling people to not pillage. Peaceful demo OK: pillage is not.” Documents obtained through a separate

FOIA request have shown that a key group behind the protests later received support from USAID and went on to play a role in the formation of Martelly’s political party, Parti Haïtien Tèt Kale.

The following day, as per Merten’s suggestion in the e-mail, the U.S. Embassy

released another statement calling for calm and urging political actors to “work through Haiti's electoral contestation process to address any electoral concerns.” As the e-mail reveals, however, efforts were underway to remove Célestin from the race before any contestation process could even begin.

Cheryl Mills’ response to Merten’s email is redacted, as is Merten’s response to that, save for one word: “Understand.”

The Haitian government eventually requested that a mission from the Organization of American States (OAS) come to Haiti to analyze the results. The mission, despite not conducting a recount or any statistical test,

recommended replacing Célestin in the runoff with Michel Martelly. Pressure began building on the Haitian government to accept the recommendations. Government officials had their U.S. visas revoked and U.S. Ambassador to the U.N. Susan Rice even went so far as to threaten to cut aid, even though the country was still recovering from the devastating earthquake earlier in the year. Mills forwarded to Rice an AFP article on the threat with a comment: “I want to make sure we are synched up over the next several sensitive days on Haiti.”

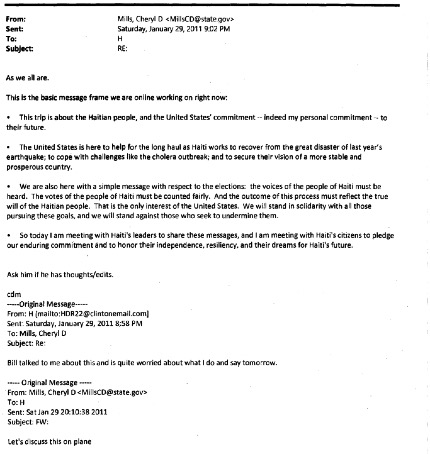

Eventually, Hillary Clinton traveled to Haiti in late January 2011 to apply further pressure on the government. The day before the trip, there was an ongoing discussion among State Department staff about potential backlash against the international community and the U.S. Mills forwarded Clinton an e-mail from Laura (the last name has been redacted, but it is likely Laura Graham, an official with the Clinton Foundation) with the message: “Let's discuss this on plane.”

“Laura”, in a long, typo-filled note, warns that the international community and U.S. are “taking hits and looking like villan [sic].” “I think you need to consider a message and outreach strategy to ensure that different elements of haitian [sic] society (church leaders, business, etc) buy into the mms [Michel Martelly] solution and are out their [sic] on radio messaging why its [sic] good,” Laura adds. Clinton responds to Mills: “Bill talked to me about this and is quite worried about what I do and say tomorrow.”

“As we all are,” Mills responds, passing along talking points for the following day’s Haiti trip:

We are also here with a simple message with respect to the elections: the voices of the people of Haiti must be heard. The votes of the people of Haiti must be counted fairly. And the outcome of this process must reflect the true will of the Haitian people. That is the only interest of the United States. We will stand in solidarity with all those pursuing these goals, and we will stand against those who seek to undermine them.

Regardless of concerns over a backlash, Clinton was successful in getting Célestin to withdraw from the race. “We tried to resist and did, until the visit of Hillary Clinton. That was when Préval understood he had no way out and accepted” it, the prime minister at the time, Jean-Max

Bellerive, told me in an interview earlier this year. After a second-round contest with exceptionally low turnout, Martelly was named the winner over Manigat.

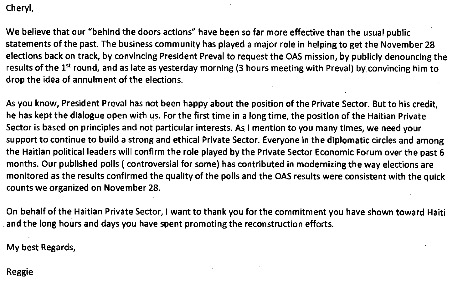

Boulos was quick to follow up after Clinton’s visit. In a long e-mail to Mills one day after the visit, Boulos asked that his thanks be passed on to the then secretary of state.

Boulos cites the private sector’s “behind the doors actions” as having “played a major role” in getting the elections “back on track” by getting Préval to “request the OAS mission, by publicly denouncing the results of the 1st round, and as late as yesterday morning (3 hours meeting with Preval) by convincing him to drop the idea of annulment of the elections.” Boulos boasted: “Everyone in the diplomatic circles and among the Haitian political leaders will confirm the role played by the Private Sector Economic Forum over the past 6 months.”

Boulos also requested that the U.S. continue its support for him and for other Haitian business elites. “We need your support to continue to build a strong and ethical private sector,” he wrote. Boulos’ commitment to building an ethical private sector is questionable, to say the least. During the 1991-1994 coup d’État, Boulos ran a USAID-funded clinic in Cité Soleil which was accused of collaborating with FRAPH, a paramilitary death squad responsible for many killings in the slum. More recently, in January 2006, following the 2004 coup against Haiti’s democratically elected government, Boulos was among a group of Haitian elites who lobbied the U.S. embassy to pressure U.N. troops to conduct assaults on Cité Soleil, and “for more ammunition for the police” to do likewise, which the U.S. charge d’affaires noted would “inevitably cause unintended civilian casualties.” A

State Department cable notes: “Boulos began reading off a specific list of needed ammunition …” (The charge, Timothy Carney, green lighted the request, as WikiLeaked cables reveal, and as we discuss in the new book, “

The WikiLeaks Files.”)

Fast forward nearly five years and Haiti once again finds itself embroiled in an electoral controversy, with the U.S., Boulos and the Private Sector Economic Forum again playing leading roles. After

violence and fraud-marred first-round legislative races were held in August, the electoral council (CEP) and Haitian government have come under increasing scrutiny. Once again, protests have taken place, calling for the resignation of the CEP and in some cases the outright annulment of the elections.

Rather than cast doubt on the results, the U.S. has supported the process. Outgoing U.S. Ambassador Pamela White

called the elections, “not perfect, but acceptable.” “It's 2010 all over again, but instead of against Preval, it's for Martelly,” a leader of the Vérite political platform, Préval’s new party

, told me in August. On October 6, Secretary of State John Kerry

travelled to Haiti to discuss the elections with Martelly. He was joined by the State Department’s new Haiti Special Coordinator, Kenneth Merten, who assumed the post on August 17.

For their part, the Private Sector Economic Forum and Reginald Boulos have also provided support to the process. Boulos was part of a

presidential advisory commission in late 2014 that recommended jettisoning Prime Minister Laurent Lamothe and forming a consensus government to take Haiti forward to the current elections. As part of the agreement to form a new government, the Private Sector Economic Forum was also made responsible for nominating one of the nine members to the electoral council. Pierre Louis Opont

was put forward as its representative. Opont was the director general of the CEP in 2010 and acknowledged in an interview earlier this year that the U.S. State Department and OAS observers manipulated the results of that election. He is the president of the current CEP.

In February, Prime Minister Evans Paul (himself part of the presidential advisory commission)

met with the Private Sector Economic Forum in order to establish a public-private partnership to create a “climate conducive to free, fair and democratic elections.”

While trust in the electoral process and the institution responsible for guiding it has eroded since the August 9 vote, Boulos and the Private Sector Economic Forum have come out publicly in support of the CEP. In an

interview with Le Nouvelliste, Boulos stated that it was “one of the best CEPs we have had.” “The CEP is not perfect but it is a CEP that has done its best, perhaps, that has made many mistakes and has acknowledged its mistakes,” Boulos told the paper. “I heard the president of the CEP say that the Council will make corrections. We should trust that he will make corrections.” “The process is advancing, the presidential campaign is on the right track,” declared Gregory Brandt, the president of the business grouping, in the same article. Brandt told the paper that he had a meeting with Opont “next week.”

First-round presidential elections as well as the second-round of the legislative elections will be held October 25.