Had this been a three-round amateur fight, Holyfield would have won going away. But now Holyfield had to complete the equivalent of four more back-to-back bouts in searing heat and against a tank-like opponent armed with savvy, toughness and grit.

The fourth opened with Holyfield showing the first signs of concession to the 15-round distance as he retreated toward the ropes and allowed Qawi to pound away at close range for nearly a full minute. With Duva yelling “turn him, turn him,” Holyfield spun away toward ring center and peppered Qawi with light but scoring punches. The intensity of those punches increased as the round continued, but, in the long-term, Qawi was getting the trench war he craved. A heavy right buckled Holyfield’s legs for the first time in the fight, but the challenger produced the perfect response by immediately snapping back with his own power shots. The already-robust action escalated to the point where ABC’s blow-by-blow man Al Trautwig declared that there was no way this fight would go 15 rounds.

Holyfield began the fifth on his toes in an effort to slow the fight down to a more comfortable level, and Qawi, sensing weakness in his opponent, turned the screws psychologically by taunting and making faces. Analyst Alex Wallau said Holyfield lacked the strength at this point to keep Qawi away or to earn his respect, and that the solution was to set his feet and drill the champion with power punches while also pivoting away from Qawi’s right hand. The fifth was Qawi’s best thus far, and, worse yet for Holyfield, his body — and his mind — was starting to rebel.

“It’s the sixth round and my back is starting to hurt,” he told Ryan. “I feel myself draining because Qawi has been coming on from the fourth round. He’s been really putting on the pressure and trying to take me out. It feels like war. Now I’m asking myself, ‘what are you doing in here?’ It’s then that you start looking for a reason to quit. I told myself ‘uh uh. You can’t quit. You have to go on.’ In the seventh round, my back hurt even worse. And Qawi kept the pressure on more and more. I just kept refusing to quit, because all my life I worked to be in this position. I said to myself, ‘what are you gonna do, fold?’ Then thoughts come to your mind, where you say, ‘well, I’m young. It won’t hurt me if I do lose this one.’ But the other side of you says, ‘no, you’re not a loser.’ In the eighth round it got even tougher, but from the ninth round on I caught my second wind. I started feeling better. I felt sharp when the bell rang for the ninth.”

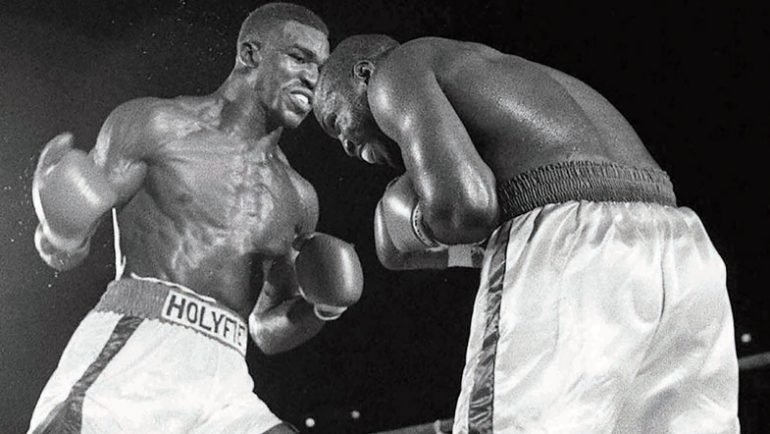

The pace during Qawi-Holyfield 1 was unrelenting. Photo by Ring Magazine/ Getty Images

In retrospect, rounds six through eight of the first Qawi fight were the most important nine minutes of Evander Holyfield’s boxing life because the successful resolution of his war between the ears served to form the foundation that would animate the remainder of his career. Had he decided to submit, he would have had to live with the consequences for the rest of his life; it would have been his first professional loss, he would have lost untold tens of millions of potential future income and he likely would have been relegated to obscurity. But because he didn’t submit, he proved to himself that he had a champion’s drive when it absolutely counted the most. Under the most intense pressure imaginable — and with his body still losing fluids at a dangerous pace — Holyfield allowed the mental to override the physical, resulting in a performance of a lifetime.

But Qawi, proud champion that he was, was the one who forced Holyfield to question himself. Shortly after Holyfield produced a burst of power shots in Round 6, Qawi ducked, dodged and weaved away from 17 consecutive punches, after which he drove in a dagger firing a more accurate 11-punch flurry, backing away, and flashing a smiling shrug. Even so, the difference in consistency and marksmanship kept Holyfield in the equation –and because clean punching is a major part of scoring fights, “The Real Deal” kept himself from being mathematically buried.

As the rounds ticked by, one could see Holyfield digging into his deepest recesses in the face of Qawi’s relentlessness while the champion sought opportunities to pounce while also doing his best to fend off the challenger’s flying fists. The styles meshed magnificently, and both men were investing full power and passion into each punch in the hopes of breaking the other. Neither succeeded, and as a result the fight went much longer than anyone had a right to believe.

The ninth saw Holyfield finally find that perfect distance in which he could land with maximum effectiveness while also limiting Qawi’s opportunities to strike. He landed his jab consistently, showed his strength by pushing Qawi away, and fired short right uppercuts and hooks without taking undue punishment in return. Holyfield stretched his advantage at the start of the 10th as his legs showed renewed life and his blows were delivered with extra speed and power. The second wind for which he had been waiting had finally arrived, and with the finish line inching closer and closer the mixture of euphoria and relief had to be palpable. But Holyfield wasn’t operating inside a vacuum; Qawi was still Qawi and he remained a never-ending threat because of his iron will, his steely chin, and his thirst for success.

Their shared goals but opposed paths continued to clash throughout the championship rounds. Having been in unknown territory since Round 9, Holyfield continued to examine the limits of his reserves by starting strongly in the opening minute only to throttle down later while Qawi, knowing he had to be behind on the scorecards in his opponents’ hometown, marched forward and seized upon any openings his wizened eyes perceived. The thousands that filled the Omni sought to boost the challenger’s energy by chanting “Holy! Holy! Holy!” but the object of their affection remained focused on living in the moment and taking care of his business.

Astonishingly, Holyfield appeared to be the fresher man during the final five rounds; an emphatic right uppercut-left hook-right cross-left hook snapped Qawi’s head late in the 13th and his improbable work rate in the 14th graphically showed just how weary the champion had become. The final round saw both men empty their chambers but Holyfield showed he had more bullets in his than Qawi did, and that, more than anything, proved to be the difference.

Fifteen seconds before the final bell, Qawi attempted one last veteran move. Shortly after taking a short right to the temple he stopped and took a couple of stuttering steps backward as if his brain had gone suddenly fuzzy. But it was all a ruse, for Qawi leapt out of his crouch and winged a desperate overhand right and hook that missed the target. Holyfield had passed one final test, and now it was up to the judges to determine whether he had earned his diploma.

Judge Gordon Volkman, a Wisconsin native, said no, as he had Qawi ahead 143-141. Neffie Quintana of New Mexico issued an overwhelming “yes” as he turned in a 147-138 scorecard in which he gave Holyfield nine of the final 10 rounds. Hall of Fame judge Harold Lederman cast the deciding vote, and, as was often the case, his score matched conventional wisdom: 144-140 for the winner…and new champion, Evander “Real Deal” Holyfield. For the record, Lederman gave Holyfield seven of the last 10 rounds.

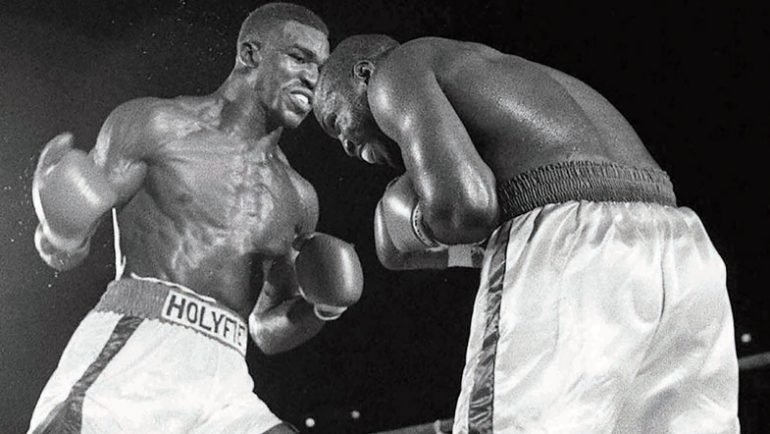

Photo by Ring Magazine/ Getty Images

It is a cliche for athletes to declare they were willing to invest their very last drop in the name of victory, but in Holyfield’s case it was the literal truth. Holyfield revealed he has lost 15 pounds during the fight and the back pain he was experiencing wasn’t just muscular but also renal; his kidneys were failing.

“I was going to go to a party after the fight, but when I went to the room to shower, I kind of stiffened up and felt nauseous and got a headache,” Holyfield told Ryan. “I called my doctor and he said we needed to get over to the hospital. He said I lost so much water that I started burning muscle. That can cause kidney failure. They put me on the IV and put nine containers in me.”

According to an October 1990 story penned by the Los Angeles Times’ Earl Gutskey, Holyfield came perilously close to permanent damage.

“First, his wife (Paulette) didn’t delay in calling for help,” said Holyfield’s doctor Ron Stephens. “Second, I lived just a mile or so away, and we were able to get a (kidney specialist) at the hospital, who was waiting for us when we arrived. We right away diagnosed him as being in severe dehydration. He was unable to urinate. We put a catheter in him and there was no urine in his bladder. We put on intravenous fluids and put 12 liters of fluid into him before he could produce a drop of urine. He was maybe a few hours away from striated muscle breakdown, and if those byproducts had clogged up his kidneys, his boxing career not only might have been over, he could have wound up on a kidney machine the rest of his life. He’s lucky his wife called when she did.”

Indeed. Holyfield stopped Qawi in four rounds in their December 1987 rematch en route to becoming an undisputed champion at cruiserweight. He then went on to become the only heavyweight in history to produce four separate championship tenures, and in a 26-year-career that ended in 2011 he produced a record of 44-10-2 (29) while also earning a plaque in Canastota as part of the IBHOF’s Class of 2017.

As for Qawi, he alternated between heavyweight and cruiserweight, with his final title opportunity coming in November 1989 against Robert Daniels for the vacant WBA belt. The 34-year-old lost by split decision, and while he ended his career with an eight-round points loss to Tony LaRosa in November 1998 while scaling a career-high 232, it was just his third loss in his last 12 fights and he ended his career at age 45 with a record eerily similar to Holyfield’s: 41-11-1 (25). By retiring 12 1/2 years before Holyfield’s final fight, he beat “The Real Deal” into the Hall of Fame by 13 years as he was inducted into the Class of 2004.

Dwight Muhammad Qawi-Evander Holyfield 1: Cruiserweight inferno 35 years later - The Ring (ringtv.com)

how the shyt has an audience is beyond me