You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Essential The Official African American Thread#2

- Thread starter Rhapscallion Démone

- Start date

More options

Who Replied?Black Lightning

Superstar

Reconstruction: America After the Civil War

Last edited:

Hoodoo Child

The Urban Legend

A Never Ending Groove

Black Lightning

Superstar

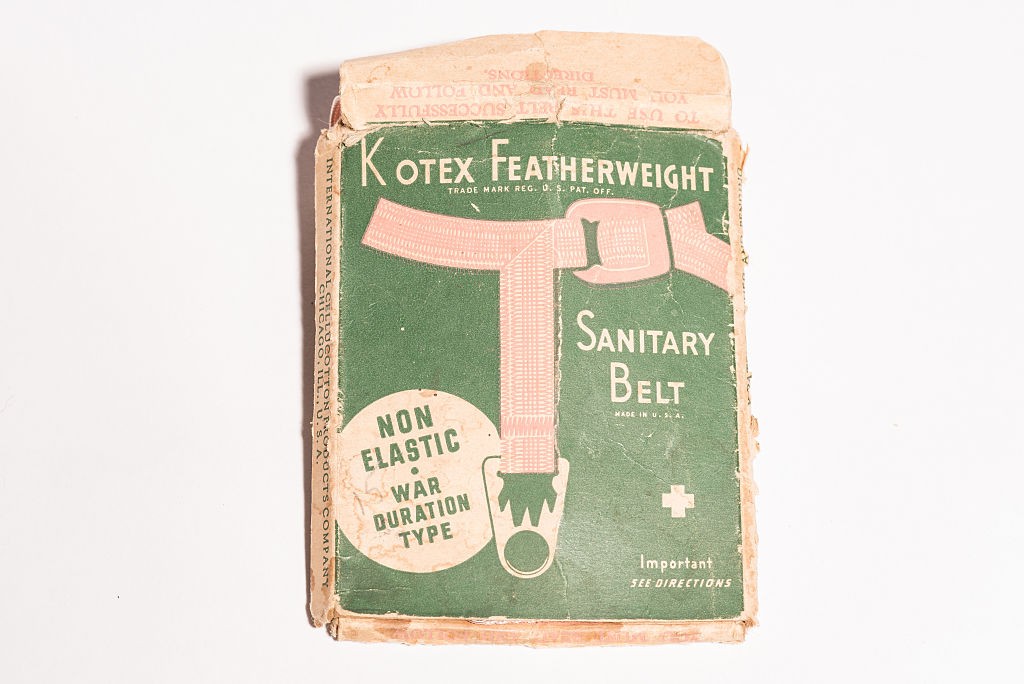

BHM: Mary Beatrice Davidson Kenner – The Forgotten Inventor Who Revolutionized Menstrual Pad

Mary Beatrice Davidson Kenner (1912–2006) always had trouble sleeping when she was growing up in Charlotte, North Carolina. Her mother would leave for work in the morning through the squeaky door at the back of their house and the noise would wake Kenner up. “So I said one day, ‘Mom, don’t you think someone could invent a self-oiling door hinge?’” She was only six at the time, but she set about the task with all the seriousness of a born inventor. “I [hurt] my hands trying to make something that, in my mind, would be good for the door,” she said. “After that I dropped it, but never forgot it.”

This pragmatic, do-it-yourself approach defined her inventions for the rest of her life. But while her creations were often geared toward sensible solutions for everyday problems, Kenner could tell from an early age that she had a skill that not many possessed. When her family moved to Washington DC in 1924, Kenner would stalk the halls of the United States Patent and Trademark Office, trying to work out if someone had beaten her to it and led a patent for an invention first. The 12-year-old didn’t find any that had done so.

In 1931 Kenner graduated from high school and earned a place at the prestigious Howard University, but was forced to drop out a year and a half into her course due to financial pressures. She took on odd jobs such as babysitting before landing a position as a federal employee, but she continued tinkering in her spare time. The perennial problem was money; filing a patent was, and is, an expensive business. Today, a basic utility patent can cost several hundred dollars.

By 1957 Kenner had saved enough money to her first ever patent: a belt for sanitary napkins. It was long before the advent of disposable pads, and women were still using cloth pads and rags during their period. Kenner proposed an adjustable belt with an inbuilt, moisture-proof napkin pocket, making it less likely that menstrual blood could leak and stain clothes.

“One day I was contacted by a company that expressed an interest in marketing my idea. I was so jubilant,” she said. “I saw houses, cars, and everything about to come my way.” A company rep drove to Kenner’s house in Washington to meet with their prospective client. “Sorry to say, when they found out I was black, their interest dropped. The representative went back to New York and informed me the company was no longer interested.”

Undeterred, Kenner continued inventing for all her adult life. She eventually filed five patents in total, more than any other African-American woman in history.

Mary Beatrice Davidson Kenner (1912–2006) always had trouble sleeping when she was growing up in Charlotte, North Carolina. Her mother would leave for work in the morning through the squeaky door at the back of their house and the noise would wake Kenner up. “So I said one day, ‘Mom, don’t you think someone could invent a self-oiling door hinge?’” She was only six at the time, but she set about the task with all the seriousness of a born inventor. “I [hurt] my hands trying to make something that, in my mind, would be good for the door,” she said. “After that I dropped it, but never forgot it.”

This pragmatic, do-it-yourself approach defined her inventions for the rest of her life. But while her creations were often geared toward sensible solutions for everyday problems, Kenner could tell from an early age that she had a skill that not many possessed. When her family moved to Washington DC in 1924, Kenner would stalk the halls of the United States Patent and Trademark Office, trying to work out if someone had beaten her to it and led a patent for an invention first. The 12-year-old didn’t find any that had done so.

In 1931 Kenner graduated from high school and earned a place at the prestigious Howard University, but was forced to drop out a year and a half into her course due to financial pressures. She took on odd jobs such as babysitting before landing a position as a federal employee, but she continued tinkering in her spare time. The perennial problem was money; filing a patent was, and is, an expensive business. Today, a basic utility patent can cost several hundred dollars.

By 1957 Kenner had saved enough money to her first ever patent: a belt for sanitary napkins. It was long before the advent of disposable pads, and women were still using cloth pads and rags during their period. Kenner proposed an adjustable belt with an inbuilt, moisture-proof napkin pocket, making it less likely that menstrual blood could leak and stain clothes.

“One day I was contacted by a company that expressed an interest in marketing my idea. I was so jubilant,” she said. “I saw houses, cars, and everything about to come my way.” A company rep drove to Kenner’s house in Washington to meet with their prospective client. “Sorry to say, when they found out I was black, their interest dropped. The representative went back to New York and informed me the company was no longer interested.”

Undeterred, Kenner continued inventing for all her adult life. She eventually filed five patents in total, more than any other African-American woman in history.

Black Lightning

Superstar

IllmaticDelta

Veteran

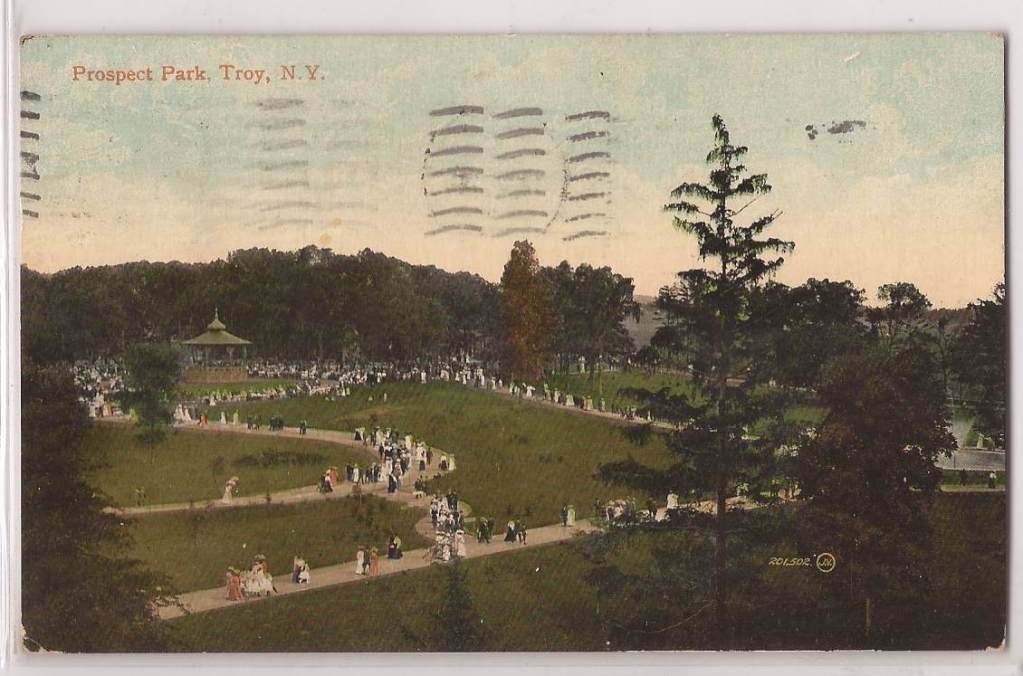

Garnet Douglass Baltimore (April 15, 1859 – June 12, 1946) was the first African-American engineer and graduate of Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, New York, Class of 1881.[1][2]

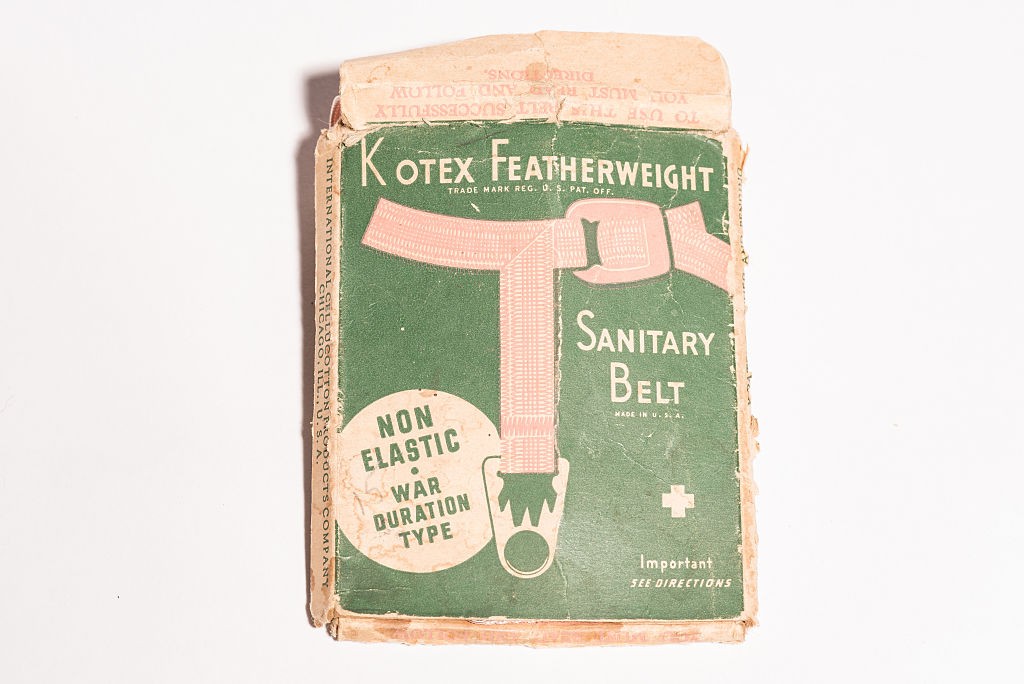

He was named for two prominent abolitionists, Henry Highland Garnet and Frederick Douglass. He was known for his architectural, engineering, and landscaping work, including Prospect Park in Troy, and Forest Park Cemetery in Brunswick, New York.[3][4]

During his work on the extension of a lock on the Oswego Canal, Baltimore developed a system to test cement that was adopted as standard by the State of New York. He was an inductee of the Rensselaer Hall of Fame. Each year Rensselaer hosts the Garnet D. Baltimore Lecture Series in his honor.

In February 2005, former Troy mayor Harry Tutunjian ceremonially renamed the section of Eighth Street between Hoosick Street and Congress Street as Garnet Douglass Baltimore Street, "as a lasting tribute to a Trojan who gave so much to his community."

.

.

.

By the middle of the 19th century, Americans realized that parks provided a spot of nature and greenery amidst an increasingly busy and industrialized world. Many men, women and children worked six days a week, and never had the time or resources to get away. Yes, parks were beautiful, but they were also very important for mental and physical health. Cities that wanted to thrive began looking for space and funding for public parks.

People from everywhere flocked to parks like Manhattan's Central Park and Brooklyn's Prospect Park. Postcards of the parks were circulated throughout the country as tourists marveled at the wonders. Many cities contemplating the development of their own parks came to see both, and many others to take notes. When the city of Troy decided to establish a new park on the top of what was called Warren Hill, one of the highest points in the city, they too looked downstate to Brooklyn for inspiration. Prospect Park gave the park’s designer some great ideas to incorporate in Troy’s own park. They also cribbed the name.

When Troy’s park first opened with a grand ceremony in 1902, they even invited dignitaries from New York City to come see it. Seth Low, one of Brooklyn’s leading citizens, and now the mayor of the newly established City of New York was invited, as well as the borough president of Brooklyn. Mr. Low had to bow out, however, and didn’t make the ceremony.

The park was still called Warren Park, however. The name wasn’t resonating with the public all that well, so the Troy newspapers decided to have a contest to rename the park. The most popular name chosen was Prospect Park. The name was approved by the Troy Common Council in 1902. It was very Brooklyn, and they knew it. Brooklyn got a kick out of it, and the Brooklyn Eagle quoted the Troy Press newspaper: “Prospect Park is admirable alliterative and beautifully Brooklynish” the paper announced.

As with its Brooklyn namesake, Troy opened Prospect Park long before it was finished. When the park had its opening ceremonies, almost all of the work in the park had yet to be done. The engineer /landscape architect chosen for the project was under tremendous pressure. The city had gone through a long bitter process just to obtain the land, so it had to be good. With all of the attention going to the new Prospect Park, Troy’s officials wanted the best man available for the job of planning and laying out this expensive and expansive plan. Fortunately, they had Garnet Douglass Baltimore on the job. He was a local RPI graduate, and a native son. He was also African American.

Garnet D. Baltimore was an inspiring man, and in many ways, the embodiment of the ideals of the city of Troy; a city that had nurtured the talents of a lot of very successful men and women. At the turn of the 20th century, Troy was at the height of its success, its fortunes made from metals, textiles, technology, education and commerce. To tell his story, we have to go back to the War of Independence, back to 1776.

During the Revolutionary War, a man named Samuel Baltimore was fighting for the nation’s freedom and also his own. He was a slave in Maryland, and his master had promised that if he fought as a soldier, he would be freed at war’s end. Baltimore took up the promise and fought long and hard. But his owner lied, and did not free him as promised. Samuel Baltimore didn’t wait, and took his own independence in hand and escaped up North soon afterward, and settled in the Hudson River town of Troy.

Troy had a small, but thriving black community. Slavery never really caught on in upstate New York, although the institution of slavery was legal until 1827, when it was finally and completely abolished. Most of New York State’s slaves were actually downstate in Brooklyn. The majority of black Trojans were either born into freedom, or like Samuel Baltimore, had escaped and made their way to this bustling river town where work was plentiful and slavery was not popular.

Samuel Baltimore settled in, got married and raised his family. His son, Peter F. Baltimore, became a successful barber in town, with a clientele that included many of Troy’s wealthiest and influential citizens. Peter Baltimore, like many Trojans, both black and white, was an ardent abolitionist. Troy was an important stop on the Underground Railroad, and one of the city’s most important abolitionists was the Reverend Henry Highland Garnet, the pastor of Troy’s Liberty Street Presbyterian Church. Like Samuel Baltimore, Garnet had taken his own independence from slavery in a remarkable story worthy of its own tale.

Peter Baltimore was a close confidant of Rev. Garnet, and was a friend of the great orator Frederick Douglass, as well. He named his son Garnet Douglass after both of them, welcoming his son into the world in 1859. The family was living at 162 Eighth Street at the time, near Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (RPI), in a house that would later fall victim to ham-handed mid-20th century urban renewal.

Growing up, young Garnet was influenced by his namesakes, as well as other influential African Americans such as mathematician Charles Reason and Underground Railroad leader Robert Purvis. Since she also had family in Troy, young Garnet probably also knew Harriet Tubman. Garnet’s father and Harriet Tubman were important players in the rescue of Charles Nalle, in one of the city’s proudest moments.

Garnet Baltimore was raised with high expectations, and he met them admirably. He was educated in Troy, and received a bachelor’s degree from RPI in 1881. He was the first African American to do so. He went on to receive a degree in Civil Engineering, and upon graduation was employed as an assistant engineer by a company building a bridge between the cities of Albany and Rensselaer. In 1883, he was in charge of a surveying party for the Granville and Rutland Railroad, a 56 mile line of track. He followed that project by being hired as an assistant engineer and surveyor on the nearby Erie Canal.

His career was not just in the Capital Region where he was known. Canal work became a specialty, and in 1884, Baltimore became head engineer in charge of building the Shinnacock and Peconic Canal in Southampton, on Long Island. The canal cuts across the South Fork of Long Island, near the Hamptons. From that project, he supervised the building of a lock on the Oswego Canal, in Western NY. That canal connected Lake Erie and Lake Ontario. The lock Baltimore was in charge of creating was a notoriously difficult one, in extremely muddy ground. It is still called the Mudlock today.

Returning to Troy, Garnet Baltimore took his skills to the land. He became a landscape architect and engineer, designing Forest Park Cemetery on the outskirts of the city in Brunswick. The cemetery’s owners wanted to outdo Troy’s famous Oakwood Cemetery, a beautiful park cemetery, the final resting place of many of Troy’s leading citizens and famous folk, including “Uncle Sam” Wilson. Garnet designed the entrance to the cemetery, planned winding trails and groves, and a receiving tomb at the entrance. Unfortunately, the project went bankrupt, and it was never completed past that point. That too, is a story worth telling for another time.

With his reputation as a civic engineer quite secure, Garnet D. Baltimore was in the perfect position to be hired to design Troy’s new Prospect Park. This being Troy, the journey was fraught with politics, and the usual battles between visionaries and cheapskates, influential citizens and pundits.

cont------>Garnet Douglass Baltimore - Troy's Master of Landscape

IllmaticDelta

Veteran

Africans, Antoney and Isabella, arrived in the British Colony of Virginia at Point Comfort (present day Fort Monroe), to become servants on the plantation of Captain William Tucker and his wife, Mrs. Mary Tucker. Captain Tucker was the Commandeering Officer at Point Comfort.

William is documented as the first child of African descent born to the parents of Antoney and Isabell, and baptized in 1624.

Descendants of William Tucker continue to reside in the Hampton Roads area.

Black Lightning

Superstar

IllmaticDelta

Veteran

John A. Lankford

(December 4, 1874 – July 2, 1946) was the first professionally licensed African American architect in Virginia in 1922 and in the District of Columbia in 1924. He has been regarded as the "dean of black architecture".[1]

John A. Lankford (1874–1946) opened one of the first black architectural offices in Washington, D.C., in 1897. A year later he designed and supervised construction of a cotton mill in Concord, North Carolina. He served as an instructor of architecture at several black colleges and as superintendent of the Department of Mechanical Industries at Shaw University in Raleigh, North Carolina. As national supervising architect for the African Methodist Episcopal Church, he designed “Big Bethel,” the landmark located in Atlanta’s historic Auburn Avenue district. His other designs included churches in South and West Africa. Lankford was commissioned to design the national office for the Grand Fountain United Order of the True Reformers, which organized one of the first black-owned banks. In the 1930s, Lankford helped to establish the School of Architecture at Howard University.

[/quote]

.

.

interesting fun fact: his great nephew is/was

^^before his "Hindu" gimmick

Korla Pandit (September 16, 1921 – October 1 or 2, 1998)

, born John Roland Redd, was an American musician, composer, pianist, organist, and television pioneer of national notability. After moving to California in the late 1940s and getting involved in show business, Redd became known as "Korla Pandit", a French-Indian musician from New Delhi, India. However, Redd was actually a light-skinned African-American man from Missouri who passed as Indian. A pathbreaking musical performer in the early days of television, Redd is known for Korla Pandit's Adventures In Music; the show was the first all-music program on television. He also performed live and on radio and made various film appearances, becoming known as the "Godfather of Exotica". Redd maintained the Korla Pandit persona—both in public and in private—until the end of his life.

Last edited:

Black Lightning

Superstar

Rest In Power

Sankofa Alwayz

#FBADOS #B1 #D(M)V #KnowThyself #WaveGod

Misconceptions About “Black Dialect”

I would like to shed some light on black dialect, which some individuals now call “Ebonics,” and how it came to be. It kinda irks me that people keep referring to it as being “made up” or some sort of street slang. They think it’s the same thing that you might hear from rappers which really isn’t the case. Black Dialect or Ebonics originated in the American south from slaves and eventually spread out when blacks began to leave the South. In fact, if you want to see or hear it in it’s true form just go find some old slave narratives or even old Blues lyrics. Rappers actually rap in a a combination of “Black Dialect” and street slang. Real black dialect has no slang. Black dialect is really Southern White American English with Africanisms. It formed the same way West African pidgins, Jamaican Patois and Creoles formed. Famous African American writers like Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston and Paul Dunbar wrote many of their works in this dialect.

What people call "Ebonics" today used to be called "Black Dialect" or "Black English". A quick history comparing "Black Dialect or Ebonics" "Gullah" and West African Pidgins

Southern American English

The Gullah Creole and "black dialect" are related. The main difference is that "Black Dialect" is closer to Standard English while Gullah has more pure African influence. One can say that "Black Dialect" is watered down Gullah. Yall may not know this but an AfroAmerican Gullah speaker and a Jamaican Patois speaker can somewhat understand each other but speakers of "Black Dialect" can't understand either one. An article take from the Jamaican-Gleaner website...

God speaks Gullah

http://www.jamaica-gleaner.com/gleaner/20060128/mind/mind1.html

.

.

.

Jamaican website REGGAEmovement.com on Patois

http://debate.uvm.edu/dreadlibrary/sullivan.html

.....and for the record, "Ebonics" is not slang. Basically, Black Dialect/AAVE/Ebonics is decreolized, Pidgin/Creole and that is closer to standard English

Do You Speak American . Sea to Shining Sea . American Varieties . AAVE . Creole | PBS

Origins: Dialect or Creole?

Do You Speak American . Sea to Shining Sea . American Varieties . AAVE . Creole | PBS

.

.

The Story Of English Program 5 Black On White

That part about “tote” meaning “to carry”...I wonder if that’s where the tote bag originates from

IllmaticDelta

Veteran

That part about “tote” meaning “to carry”...I wonder if that’s where the tote bag originates from

A tote bag is a large and often unfastened bag with parallel handles that emerge from the sides of its pouch. The word tote is probably African in origin and came into English via Gullah. Totes are often used as reusable shopping bags.

Tote bag - Wikipedia

Black Lightning

Superstar

1898 Wilmington

1921 Black Wall Street

1921 Black Wall Street

NASA Astronaut Jeanette Epps to Become 1st Black Woman to Join International Space Station Crew

BY GOODBLACKNEWS ON AUGUST 28, 2020

NASA astronaut Jeanette Epps is now poised to be the first Black woman crew member of the International Space Station (ISS), according to sciencetimes.com.

On Tuesday, Epps was assigned to the NASA Boeing Starliner-1. The African-American aerospace engineer and astronaut will join the space administration’s first operational crewed flight for Boeing’s CST-100 Starliner spacecraft, in a mission to the ISS.

To quote the Science Times article:

The Boeing Starliner-1 mission will be the first for Jeanette Epps. She first earned a bachelor’s degree in physics from Le Moyne College, in her hometown of Syracuse, New York. She then completed her master’s degree in science and her doctorate in aerospace engineering, both from the University of Maryland.

While she was pursuing her master’s and doctorate, Epps received a NASA Graduate Student Researchers Project (GSRP) Fellowship grant, publishing several academic papers on the way. After her doctorate, she started working in a research lab with the Ford Motor Company for more than two years before moving to the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), where she was a technical intelligence officer for seven years.

RELATED:Pioneering Astronaut Mae Jemison Offers Insight and Forward Thinking to New National Geographic Channel Series “One Strange Rock”

In 2009, she was selected as a member of that year’s astronaut class. In January 2017, NASA astronaut Jeanette Epps was assigned to be a part of Expeditions 56 and 57. She was set to fly into Earth’s orbit aboard a Russian Soyuz spacecraft. This was supposed to be the first long-duration ISS mission, including an African-American astronaut.

However, on January 16, 2018, NASA announced that Jeanette Epps would be reassigned to future missions, being replaced by her backup Serena M. Auñon-Chancellor. The reason for the reassignment was never officially explained.

There have been some Black Americans who have traveled to and from space, with a former fighter pilot and astronaut Guion Bluford being the first as a crew member of the 1983 Challenger. However, there has been no Black American assigned to live and work in space for more extended periods. The International Space Station has already seen 240 individuals across 395 spaceflights, since 2000.

Epps will be joining NASA astronauts Sunita Williams and Josh Cassada.

Based on NASA’s current schedule, the first Black astronaut to live and work on the ISS will likely be Victor Glover, who is set to head there on the SpaceX Crew-1 mission on Oct. 23.

To read more: Jeanette Epps Set to Be the First Black Woman to Join ISS Crew