Brehs that know more about economics, with immigration currently at a halt and more illegals being sent away, will the conditions of AA's (economically) improve or nah? Seems that logically it should

I don't know breh, they talking bout going to war with China now. As if we can afford that.Brehs that know more about economics, with immigration currently at a halt and more illegals being sent away, will the conditions of AA's (economically) improve or nah? Seems that logically it should

.

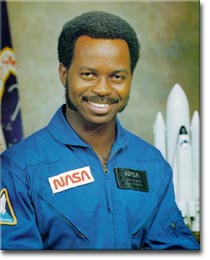

George W. Gibbs, Jr. was the first person of African descent to set foot on Antarctica (the South Pole). He was also a civil rights leader and World War II Navy gunner.

Gibbs was born in Jacksonville, Florida on November 7, 1916. He moved to Brooklyn, New York where he enrolled in Brooklyn Technical School and later received his GED. He also served in the Civilian Conservation Corps in the 1930s.

Gibbs served on Admiral Richard Byrd’s third expedition to the South Pole in 1939-1941, becoming the first African American to reach Antarctica. From more than 2,000 Navy applicants, Gibbs was among the 40 chosen to accompany Byrd in this history making expedition, sailing on the USS Bear. The USS Bear was a floating museum before the old wooden vessel was specially outfitted for the South Pole expedition. Gibbs was a member of the crew that supported the ice party. He was the first person off the ship to set foot on Antarctica on January 14, 1941.

During World War II Gibbs served as a naval gunner in the South Pacific. Gibbs remained in the Navy after the war and served for 24 years before retiring in 1959 with the rank of Chief Petty Officer. Following the war, Gibbs returned to college and graduated from the University of Minnesota with a Bachelor of Science degree in Education.

On September 26, 1953 Gibbs married Joyce Powell in Portsmouth, Virginia. After he completed his college degree the couple moved to Rochester, Minnesota in 1963 where Gibbs worked for IBM in the personnel department. During his career at IBM he was a corporate housing administrator and international assignment representative. After retirement from IBM in 1982 Gibbs managed his own employment agency until his final retirement in 1999.

In 1966 George Gibbs helped organize the Rochester Chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and worked for civil rights both locally and nationally. He also served as president of the Rochester Kiwanis and the Rochester chapter of the Minnesota Alumni Association. Gibbs was presented with the George Gibbs Humanitarianism Award by the Rochester, Minnesota branch of the NAACP, just one of many honors he received in his life.

In 1974 Gibbs applied for membership to the Rochester Elks Club. He made national news when the Club initially denied him entry. He was the first African American to apply to the local club and helped break the color barrier at service clubs in Rochester.

George W. Gibbs died November 7, 2000, on his 84th birthday. On October 11, 2009, George Gibbs Elementary School opened in Rochester, Minnesota, named in his honor. In 2002, Rochester's West Soldiers Field Drive was renamed in Gibbs' honor. Gibbs Point in Antarticia was named after him on September 2, 2009.

Deeper Than Rap: The Black Influence on All of American Music

JUNE 27, 2011 · 3 COMMENTS

CULTURE · TAGGED: BLUES, CHUCK BERRY, COUNTRY, JESSICA BENNETT, RAP, RAY CHARLES, ROCK N ROLL, SOUL

Considering the past 30 years, it is safe to say that hip-hop has taken over as the dominant musical genre of expressing African-American views. R&B and soul music also carry on the tradition, with a wide range of artists dedicated to keeping the old school feeling of rhythm & blues alive. That being said, it is easy to forget how much African Americans have influenced other genres, such as rock ‘n roll, country and others, since there are so few well known artists of color in those genres today. The Black influence on American music is greatly underappreciated, and for Black Music Month, it should be brought to light just how much African-Americans have contributed.

When we look at and listen to rock stars today, we tend to see slim, white guys with ripped jeans and long hair, wailing barely audible lyrics over a thrashing guitar riff. It may not be everyone’s taste, but it does have its place, and can be a very lively and fun experience. With artists varying from The Beatles to Bruce Springsteen, from Nirvana to Marilyn Mansion, we rarely see the link to Black folks within the context of modern rock. But as many know, the so called “King of Rock ‘N Roll” Elvis Presley owes a great deal to the life of several Black artists, namely Chuck Berry, who for many is the real King of Rock. Artists such as Berry, Ike Turner and Little Richard were producing the kind of music Elvis, The Rolling Stones and other rock heavyweights mimicked for years to come. It indeed grew and changed from its original incarnation as it spread throughout the country and around the world, but the southern black roots of rock ‘n roll cannot be denied.

Similarly, today’s country music today is associated with white southerners equipped with a cowboy hat and an acoustic guitar. Yes, there are many folk artists that were indeed white and helped in the development of what country has become, but it should also be made clear that country has strong roots in blues music, especially in the storytelling/lyrical aspect of things. As the legendary Etta James once said, “The blues and country are cousins,” and that is easy to believe when you listen to a masterful artist such as Ray Charles who navigated through several genres seamlessly, and whose music greatly influenced how country grew and developed throughout the years.

African-Americans have left their mark on every form of American music, so why is it so difficult for us to expand beyond hip-hop and R&B in today’s cultural landscape, when we had such a hand in other genres those many years ago? One answer could simply be the expectations and limitations we place on ourselves. At every major awards show focused on African-Americans, is there ever a best country category? Best Rock? Best Electronica? No, there isn’t. Why? It isn’t because there aren’t any Black people who fit the category, it’s because we tend to limit our thinking to what the majority deems successful, instead of acknowledging our full selves as artists. In today’s music industry, there could be a possible shift in this mentality. With the melding of multiple genres, it feels as if all races could get away with doing whatever kind of music they choose. A white, female rapper? Sure. A Black guy from the projects doing house music? Why not? We’ve come too far to limit ourselves, and it’s about time we embrace all of what the arts have to offer, especially when our people worked so hard to build it.

– Jessica Bennett

* * * *

Jessica Bennett is a freelance music journalist who also goes by “Compton” and “Soulfullyreal.” All three of them are Hip Hop Heads with a column entitled “Welcome to Compton”. For daily musings, check her out at @soulfullyreal.

Deeper Than Rap: The Black Influence on All of American Music - Soul Train

Nothing but facts.One can easily make the case that if you removed the Afram influence, there would be no such thing as what came to be global pop music.

African American Hoodoo(also known as "conjure", "rootworking", "root doctoring", or "working the root") is a traditional African American folk spirituality that developed from a number of West African spiritual traditions and beliefs.

Hoodoo is the practice of spirituality carried to the United States by West Africans as the result of the Transatlantic Slave Trade. It is a blend of practices from the people of the Kongo, Benin/Togo, Nigeria and others. The extent to which hoodoo could be practiced varied by region and the temperament of the slave owners. Enslaved Africans of the Southeast, known as the Gullah, as well as those in Louisiana, were people who enjoyed an isolation and relative freedom that allowed for retention of the practices of their West African ancestors. Rootwork or hoodoo, in the Mississippi Delta where the concentration of enslaved Africans was dense, was practiced but under a large cover of secrecy. Hoodoo spread throughout the United States as African Americans left the Delta during the Great Migration.

The word hoodoo stems from Hudu, which is the name of a language and a Ewe tribe in Togo and Ghana.[citation needed] It was first documented in American English in 1875 and was used as a noun (the practice of hoodoo) or a transitive verb, as in "I hoodoo you," an action carried out by varying means. The hoodoo could be manifest in a healing potion, or in the exercise of a parapsychological power, or as the cause of harm which befalls the targeted victim.[1] In African American Vernacular English (AAVE), hoodoo is often used to describe a paranormal consciousness or spiritual hypnosis, a spell. But hoodoo may also be used as an adjective for a practitioner, such as "hoodoo man".

Known hoodoo spells date back to the 1800s. Spells are dependent on the intention of the practitioner and "reading" of the client.[2]

Regional synonyms for hoodoo include conjuration, witchcraft, or rootwork.[3] Older sources from the 18th and 19th century sometimes use the word "Obeah" to describe equivalent folk practices.[4]

n this book, Katrina Hazzard-Donald explores African Americans' experience and practice of the herbal, healing folk belief tradition known as Hoodoo. Working against conventional scholarship, Hazzard-Donald argues that Hoodoo emerged first in three distinct regions she calls "regional Hoodoo clusters" and that after the turn of the nineteenth century, Hoodoo took on a national rather than regional profile. The first interdisciplinary examination to incorporate a full glossary of Hoodoo culture, Mojo Workin': The Old African American Hoodoo System lays out the movement of Hoodoo against a series of watershed changes in the American cultural landscape. Throughout, Hazzard-Donald distinguishes between "Old tradition Black Belt Hoodoo" and commercially marketed forms that have been controlled, modified, and often fabricated by outsiders; this study focuses on the hidden system operating almost exclusively among African Americans in the Black spiritual underground.

John the Conqueror, also known as High John the Conqueror, John de Conquer, and many other folk variants, is a folk hero from African-American folklore. He is associated with a certain root, the John the Conqueror root, or John the Conqueroo, to which magical powers are ascribed in American folklore, especially among the hoodoo tradition of folk magic.

A black cat bone is a type of lucky charm used in the African American magical tradition of hoodoo. It is thought to ensure a variety of positive effects, such as invisibility, good luck, protection from malevolent magic, rebirth after death, and romantic success.[1]

...Got a black cat bone

got a mojo too,

I got John the Conqueror root,

I'm gonna mess with you...

—"Hoochie Coochie Man," Muddy Waters

The bone, anointed with Van Van oil, may be carried as a component of a mojo bag; alternatively, without the coating of oil, it is held in the charm-user's mouth.[2]

Mojo /ˈmoʊdʒoʊ/, in the African-American folk belief called hoodoo, is an amulet consisting of a flannel bag containing one or more magical items. It is a "prayer in a bag", or a spell that can be carried with or on the host's body.

Alternative American names for the mojo bag include hand, mojo hand, conjure hand, lucky hand, conjure bag, trick bag, root bag, toby, jomo, and gris-gris bag.[1]

Goofer dust is a traditional hexing material and practice of the African American tradition of hoodoo from the South Eastern Region of the United States of America.

LIttle Known Black History Fact: The Fultz Quadruplets

Little Known Black History Fact: The Fultz Quadruplets

The Fultz Quadruplets were the first identical Black quad babies born in the United States. The Fultz girls became baby celebrities, while Fred Klenner, the white doctor who delivered them into the world, exploited them for fame and money.

The Fultz Quads – Mary Louise, Mary Ann, Mary Alice, and Mary Catherine – were born on May 3, 1946 at Annie Penn Hospital in Reidsville, N.C. The Quads’ parents, sharecropper Pete and deaf-mute mother Annie Mae, lived on a farm with their six other children but were too poor to care for the babies. Multiple births were rare at the time and the equipment to care for underweight babies wasn’t as prevalent as it is in modern times.

The girls were delivered in what was known as “the Basement,” according to a 2002 report by journalist and educator Lorraine Ahearn. This “basement” was the Blacks-only wing of Annie Penn, and Klenner and Black nurse Margaret Ware helped Annie Mae give birth. Since the Fultz family couldn’t read or write, Dr. Klenner named the girls after his own family members.

When news of the quads began to spread nationwide, curious onlookers and media began sniffing around for photo opportunities. At the time, baby formula companies such as Gerber and PET wanted to use the quads as a means to start an ad campaign to sell their wares in the Black community. Black families didn’t buy formula during the late ’40’s, as many mothers opted to breast feed because of the high cost of baby formula.

Klenner struck a deal with PET for an undisclosed amount and the Fultz Quads were well on their way to becoming stars. The quads’ starred in ads in Ebony Magazine, and they even made the cover of the publication. But all of this notoriety came with a price as Klenner used the girls for his “Vitamin C therapy” that he claimed made the girls healthy along with the PET evaporated milk formula.

While Klenner reaped the financial benefits, PET Milk company gave the Fultz quads a farm, a nurse, food, and medical care. Even more shocking, when Klenner returned the girls home, he displayed them in a glass-enclosed nursery. In a follow up story reported by Ebony, the then 22-year-old sisters were ultimately adopted by the nurse PET assigned to them and her husband. They struggled with adulthood. The farm they were given was on difficult land, and Pet paid the quads just $350 a month, leaving them virtually broke.

The girls became the third set of quadruplets in America to survive until adulthood. But according to Ahearn’s story, three of the sisters died of breast cancer before age 55, with Catherine Fultz Griffin believed to be the last surviving Fultz quadruplet.

(Photo: JFK Library, Public Domain)

I'm from Reidsville and I never knew about this.

I'm from Reidsville and I never knew about this.