cole phelps

Superstar

http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/5127/

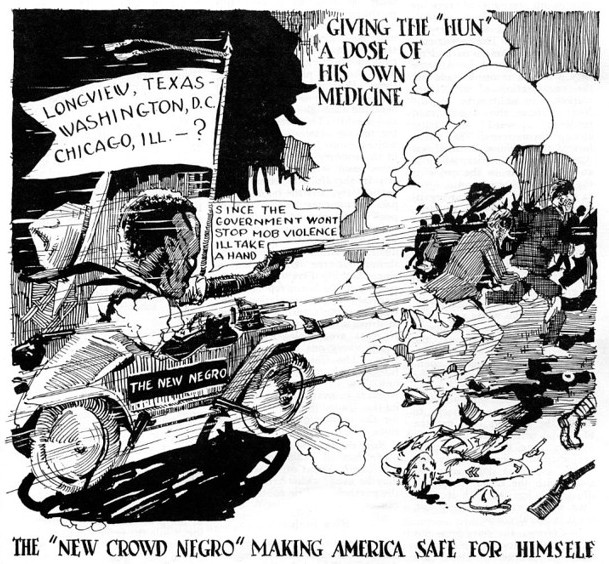

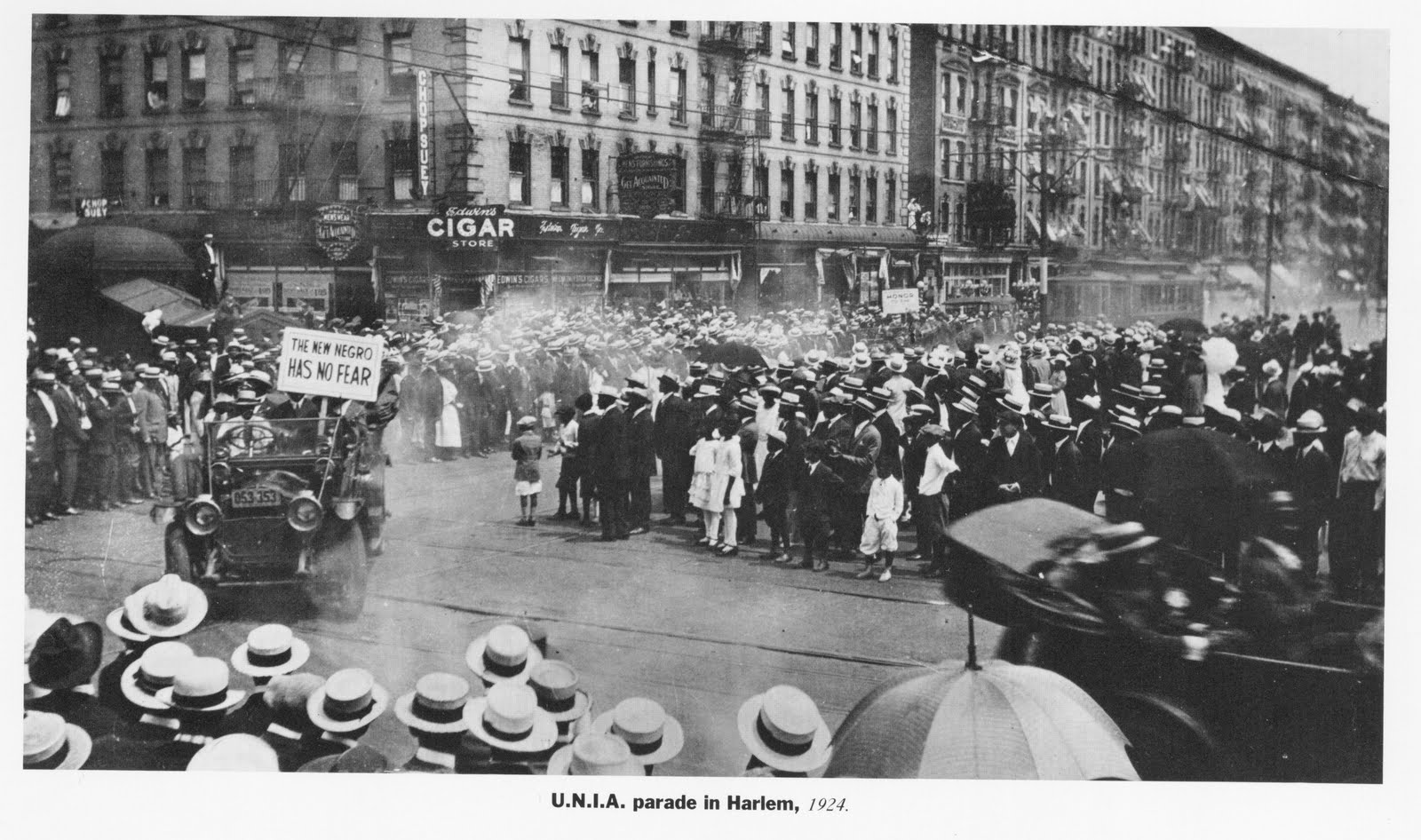

In the years immediately following World War I, tens of thousands of southern blacks and returning black soldiers flocked to the nation’s Northern cities looking for good jobs and a measure of respect and security. Many white Americans, fearful of competition for scarce jobs and housing, responded by attacking black citizens in a spate of urban race riots. In urban African-American enclaves, the 1920s were marked by a flowering of cultural expressions and a proliferation of black self-help organizations that accompanied the era of the “New Negro.” Many black leaders, including religious figures, embraced racial pride and militancy. This 1921 article by Rollin Lynde Hartt, a white Congregational minister and journalist, captured well what was “new” in the New Negro: an aggressive willingness to defend black communities against white racist attacks and a desire to celebrate the accomplishments of African-American communities in the North.

The other evening five hundred Knights of the Ku Klux Klan marched in procession thru Jacksonville, Florida—a “band of determined men,” who “would brook no interference.” Fifteen southern states now have Ku Klux organizations—their emblem, the “flaming cross”; their device, “We Stand for Chivalry, Humanity, Mercy, Patriotism”; their advertisement, a shield bearing skull and cross-bones. Specimens of that advertisement, clipped from southern papers, are shown to visitors at the headquarters of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People in New York City.

Southerners recall that during Reconstruction the South owed much to the Ku Klux, Northerners, however unsympathetic, find that it accomplished its purposes. Can it accomplish its purposes today, or is it perhaps destined to end by defeating them if not actually bringing about the very situation it aims to forestall? There are friends of the South who, having studied the evolution of the new negro, harbor serious misgivings. No mere fanciful bugaboo is the new negro. He exists. More than once I have met him. He differs radically from the timorous, docile negro of the past. Said a new negro, “Cap’n, you mark my words; the next time white folks pick on colored folks, something’s going to drop—dead white folks.” Within a week came race riots in Chicago, where negroes fought back with surprising audacity.

Another new negro, home from overseas said, “We were the first American regiment on the Rhine—Colonel Hayward’s, the Fighting Fifteenth; we fought for democracy, and we’re going to keep on fighting for democracy till we get our rights here at home. The black worm has turned.”

I said, “There is a high mortality among turning worms. We’ve got you people eight to one.”

He answered, “Don’t I know it? Thousands of us must die; but we’ll die fighting. Mow us down—slaughter us! It’s better than this.”

I remembered seeing a negro magazine shortly after the Chicago riots; a war-goddess on its cover brandished aloft her sword. “They who would be free,” ran the legend, “must themselves strike the blow.” I remembered a telegram from a negro editor, “Henceforward, an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth, a life for a life.” Here, in this colored veteran, was the same spirit—the spirit, that is, of the new negro. Hit, he hits back. In a succession of race riots, he has proved it. “When they taught the colored boys to fight,” says a negro paper, “they started something they won’t be able to stop.”

This is apparently no transient mood. The evolution of the new negro has been in progress since 1916, when southern negroes began to move North. That huge, leaderless exodus—a million strong, according to Herbert J. Seligmann, author of “The Negro Faces America”—stronger by far, according to some authorities—meant that for the first time in history the negro had taken his affairs into his own hands. Until then, things had been done to the negro, with the negro, and for the negro, but never by the negro. At last, he showed initiative and self-reliance. Despite the lure of big wages “up North,” it required no little courage. If the vanguard was exploited, the exploitation continued and still continues. In an article on “The High Cost of Being a Negro,” the Chicago Whip declares, “In Chicago, Kansas City, New York and Detroit, where negroes are working, they have to pay twice the rent, and in neighborhood clothing and grocery stores recent investigations show that for the same goods

the negro has to pay a color tax sometimes as high as 50 per cent. Thus the net earnings, if any at all, are 50 per cent less than those of the white workers.” Yet the exodus from Dixie goes on. Few—astonishingly few—return.

Last edited: