http://www.slate.com/articles/news_...long_tradition_of_black_americans_taking.html

Part 1

Red Summer

In 1919, white Americans visited awful violence on black Americans. So black Americans decided to fight back.

By

Rebecca Onion

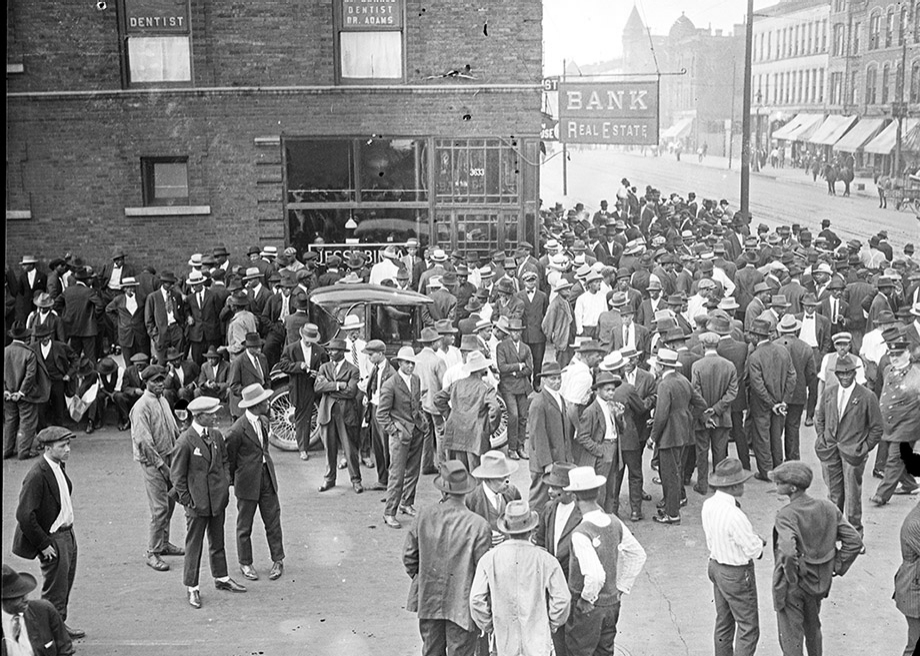

Men outside of the office of black Chicago businessman Jesse Binga, summer of 1919. “During Chicago’s riot,” writes David Krugler, “African-Americans gathered on street corners in the riot zone to share news and to form self-defense forces.”

Photo by Jun Fujita. Courtesy of the Chicago History Museum (ICHi-65481).

In Longview, Texas, in July 1919, S.L. Jones, who was a teacher and a local distributor of the blacknewspaper the

Chicago Defender, investigated the suspicious death of Lemuel Walters. Walters was a black man who was accused of raping a white woman, jailed, and ultimately found dead under “mysterious” circumstances. When the

Defender published a story about Walters’ death, asserting that the alleged rape had been a love affair and Walters’ death the result of a lynching, Jones came under attack, beaten by the woman’s brothers.

Hearing a rumor that Jones was in trouble, Dr. C.P. Davis, a black physician and friend of the teacher, tried to get law enforcement to protect him from further violence.

When it became clear that this help was not forthcoming, Davis organized two-dozen black volunteers to guard Jones’ house. That same night, a mob surrounded the dwelling. Four armed white men knocked on the door, then tried to ram it down. The black defenders, who were arranged around Jones’ property, opened fire. A half-hour gun battle ensued, in which several attackers were wounded; the posse retreated.

Hearing the town’s fire bell ringing to summon reinforcements, Jones and Davis went into hiding, knowing that they wouldn’t be able to defend themselves against a larger mob.

Davis borrowed a soldier’s uniform, put it on, and took the first of several trains out of the area. At one point, he asked a group of black soldiers he found in a train car to conceal him in their ranks, which they did, contributing to his disguise by giving him an overseas cap and a gas mask. Later that day, Jones also managed to escape. But their successful resistance and flight were bittersweet victories: Before the episode was over, Davis’ and Jones’ homes were burned, along with Davis’ medical practice and the meeting place of the town’s Negro Business Men’s League. Davis’ father-in-law was killed in the violence.

In his new book,

1919, The Year of Racial Violence: How African Americans Fought Back, David F. Krugler, professor of history at the University of Wisconsin–Platteville, looks at the actions of people like Jones and Davis, who resisted white incursions against the black community through the press, the courts, and armed defensive action. The year 1919 was a notable one for racial violence, with major episodes of unrest in

Chicago; Washington; and

Elaine, Arkansas, and many smaller clashes in both the North and the South. (James Weldon Johnson, then the field secretary of the NAACP,

called this time of violence the “Red Summer.”) White mobs killed 77 black Americans, including 11 demobilized servicemen (according to the NAACP’s magazine, the

Crisis). The property damage to black businesses and homes—attacks on which betrayed white anxiety over new levels of black prosperity and social power—was immense.

The history of black responses to the violence of 1919—which ranged from the use of a single weapon against a home invader, to the organization of defensive posses like Davis’ that were meant to protect potential victims of lynching, to the deployment of groups of men who patrolled city streets during unrest—makes it clear that armed self-defense, far from being an invention of Malcolm X and the Black Power movement, is a strategy with deep roots. As we celebrate the 50th anniversary of the civil rights movement, the story of nonviolence—a beautiful strategy with uncontestable moral force—has taken center stage.

However the story of active self-defense against violence—a tradition that developed before, and then alongside, nonviolent resistance—is too often dismissed or simply ignored. Even before slavery had been outlawed, black Americans took up arms when their lives and livelihoods were threatened. Their experiences make the familiar history of marches and peaceful protest more complex. But the story of the civil rights struggle is incomplete without them.

the New Negro. That year, poet Claude McKay published his sonnet “

If We Must Die” in the socialist magazine the

Liberator:

Though far outnumbered let us show us brave,

And for their thousand blows deal one death-blow!

What though before us lies the open grave?

Like men we’ll face the murderous, cowardly pack,

Pressed to the wall, dying, but fighting back!

Activists followed these calls for resistance with attempts to work within the legal system to defend those who fought back. After each episode of violence, the NAACP took new legal initiative in prosecuting white rioters and representing black people who had acted to defend themselves. Sometimes, as in the aftermath of the violence in Longview, Texas, NAACP lawyers were able to get prisoners who had been found with weapons released by arguing that their actions were taken in self-defense. These legal victories—though somewhat diminished by the difficulty lawyers had in landing convictions of white rioters—were nonetheless significant.

.

.