You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The Horn of Africa Current Events Thread

- Thread starter Yung Pharaoh

- Start date

-

- Tags

- africa horn of africa

More options

Who Replied?Sudan Will Decide the Outcome of the Ethiopian Civil WarIt is behind a paywallcould you post it here.

As Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed goes to war against Ethiopia’s former rulers —the Tigray People’s Liberation Front—Khartoum’s moves will determine whether the conflict remains a local affair or a regional conflagration.

BY NIZAR MANEK, MOHAMED KHEIR OMER NOVEMBER 14, 2020, 8:22 AM

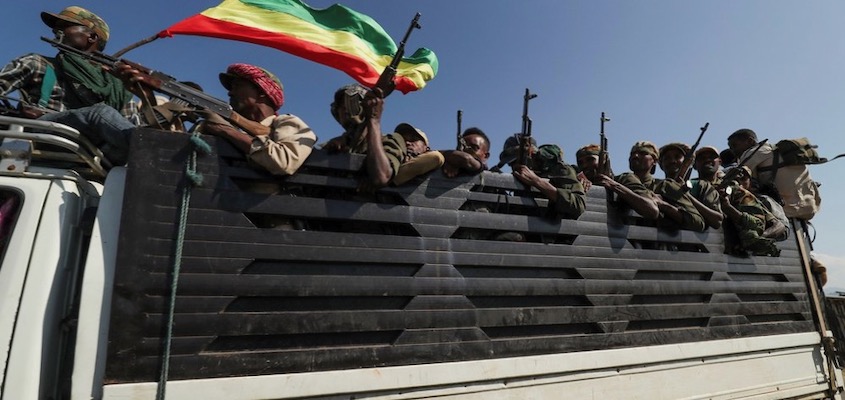

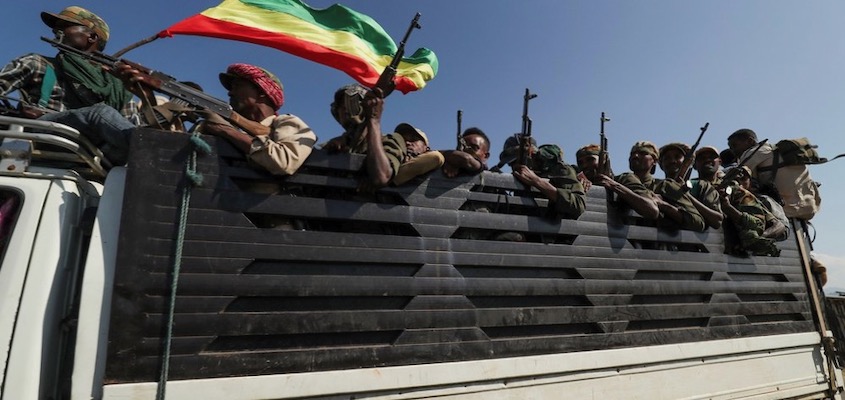

ADDIS ABABA, Ethiopia—While the world girded for the U.S. election in early November, Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed launched a war against the northern region of Tigray. The region is home to the Tigray People’s Liberation Front—the party that dominated Ethiopian politics for decades and has since been displaced and sidelined as Abiy has sought to consolidate power and made peace with the TPLF’s archenemy, Eritrea.

But the TPLF has not gone quietly; in September, the regional government it leads held local elections that the central government refused to recognize in October. Then, on Nov. 3, following provocations by Abiy, it took control of personnel, military hardware, and equipment from the federal army’s Northern Command, prompting Addis Ababa to declare war against a region that remains home to a sizable portion of the Ethiopian federal army’s arsenal and forces, given its position along the long- contested and still undemarcated border with Eritrea.

Abiy has long accused the TPLF old guard of seeking to sabotage his government and his purported reforms. But now, facing all-out war against

a formidable foe, the outcome will turn on the choices of Ethiopia’s neighbors—Sudan and Eritrea.

Although Tigray is small, it is well armed, and its forces are battle-hardened. Tigray’s regional special forces, which a senior Ethiopian diplomat estimates have grown to at least 20,000 commandos—led by senior Tigrayan officers forced into retirement by Abiy, plus a standing body of reserve special forces made up of military-trained militia and armed farmers—together have an estimated total of up to 250,000 armed fighters. Until recently, however, it lacked the heavy weaponry required to directly confront a fully-equipped division.

Since last week, the TPLF has taken control of half the soldiers from the five divisions of the Ethiopian National Defense Forces (ENDF) Northern Command that remain in Tigray—meaning it has gained 15,000 soldiers, according to three sources: a senior Ethiopian diplomat briefed on the latest developments, a senior retired intelligence officer in Tigray who continues to work for the TPLF, and a source in Tigray monitoring the situation. But the seizure of Ethiopian military hardware and equipment has heightened the importance of logistical supplies for the TPLF, which will inevitably depend on Sudan’s stance.

Sudan has a number of strategic reasons to back—or at least to be perceived as supporting—the TPLF in the civil war against Ethiopia’s government.

While Sudan has officially closed the borders between Tigray and Sudan’s frontier states of Kassala and Gadaref—which are landlocked Tigray’s only logistical links to the outside world in terms of fuel, ammunition, and food —it could use the threat of support to the TPLF to extract concessions from Addis Ababa on the contested Fashqa triangle.

Fashqa is an approximately 100-square-mile territory of prime agricultural land along its border with Ethiopia’s Amhara state, which Sudan claims by virtue of an agreement signed in 1902 between the United Kingdom and Ethiopia under Emperor Menelik II and subsequently reinforced by various Ethiopian leaders, including the TPLF.

The dispute over Fashqa remains a major grievance for Ethiopia’s ethnic Amhara farmers near the border, who seek to till the land, and is an obstacle in negotiations over the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD). Like Egypt, Sudan has rejected Ethiopia’s proposal for guidelines that would enshrine Ethiopia’s future ability to manage annual flow of the Blue Nile on a discretionary basis and Khartoum is already using the issue as leverage to pressure Abiy on Fashqa, where Ethiopia and Sudan continue to maintain a military presence.

But if Sudan supports Tigray, which also borders Eritrea, the civil war will certainly become a protracted affair, and the strategic fallout in Khartoum’s relations with Addis Ababa and Asmara could be too high. Indeed, the region could quickly revert to the state of proxy conflict that preceded the rise of Abiy and the collapse of former Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir’s regime—or precipitate a wider regional conflagration.

Since last week, Sudan has already seen thousands of people flee from Ethiopia, including officers from the ENDF, according to a source who has spoken with Sudan’s civilian prime minister, Abdalla Hamdok, about the matter. While Bashir allied himself with Ethiopia’s former TPLF-led regime, the TPLF’s influence in Khartoum has become limited since Bashir fell from power, and because it no longer controls the Ethiopian state.

Sudan’s condition is already fragile, and it wants to ensure that it has at least minimal relations with its neighbors. For now, instructions from Khartoum have focused on not alienating either Addis Ababa or Asmara— a message that has trickled down in the Sudan Armed Forces, which has deployed to its borders with Ethiopia, said a senior Sudanese military officer.

Sudan’s condition is already fragile, and it wants to ensure that it has at least minimal relations with its neighbors.

Sudan is not the only neighboring country with a strong interest in the outcome of the civil war. Envoys of Eritrean President Isaias Afwerki traveled to Khartoum on Nov. 11 to see the chairman of Sudan’s transitional Sovereign Council, Lt. Gen. Abdel Fattah al-Burhan—presumably to ask Sudan’s military, which holds the real power, to cut off any potential logistical support to the TPLF.

From the beginning, it was clear that Abiy was intent on provocation, but he did not anticipate the TPLF could supplant an entire military command. In late October, a week before the TPLF took control of the remaining Northern Command in Tigray, Abiy created a new regional command in Ethiopia’s Amhara state, with the two divisions of the Northern Command already stationed in Amhara slated to be transferred into its ranks.

The Northern Command comprises eight of the ENDF’s 32 divisions. Three of them have been stationed outside of Tigray for two years, since Abiy expanded the operational area of the Northern Command: a tank division in the north of Ethiopia’s Afar state and two divisions in Amhara. Military maneuvers against Tigray are now underway on three fronts: from Eritrea, Afar, and Amhara, with Eritrea and Amhara being used in an attempt to cut the TPLF off from Sudan.

On Nov. 1, a few days after Abiy created the new command, Burhan flew to see him in Addis Ababa with the director-general of Sudan’s intelligence service and the head of military intelligence. It was announced that they would strengthen control of the Ethiopia-Sudan border, suggesting that Abiy was trying to completely encircle Tigray before a premeditated confrontation with the TPLF.

Both Abiy and Isaias—who went to war with the TPLF’s leaders two decades ago, leading to a bloody Ethiopian-Eritrean conflict that lasted, on and off, for 20 years—have a bloodlust for the TPLF. This shared hostility toward Ethiopia’s former regime, rather than any brotherly love, was the principal motivation for their commencement of diplomatic relations two years ago, for which Abiy was feted with last year’s ill-judged Nobel Peace Prize; the Norwegian Nobel Committee failed to see that the prize rewarded a peace process that really intended to end one war while laying the groundwork for another, as it has today.

Abiy was feted with last year’s ill-judged Nobel Peace Prize; the Norwegian Nobel Committee failed to see that the prize rewarded a peace process that really intended to end one war while laying the groundwork for another

According to sources in both Tigray and the Ethiopian government, soldiers in divisions of the ENDF Northern Command in Tigray have in the past week split into three groups: half aligned with the TPLF, one-quarter —Abiy loyalists and mostly ethnic Amhara officers—fled into Eritrea, and the rest refused to fight against the federal army and have been contained in barracks. The sources in Tigray were able to speak with us intermittently over satellite Internet, circumventing the telecommunications shutdown Abiy has imposed there.

While the TPLF had considerable success last week in taking control of personnel, military hardware, and equipment held by the divisions of the ENDF’s Northern Command, continued success in a protracted civil war will ultimately depend on support from Sudan.

Sudan has a long history of involvement in Ethiopian and Eritrean affairs. Even before the TPLF and Isaias came to power in the 1990s, Sudan clandestinely supported both the TPLF and the Eritrean Liberation Front (ELF) in allowing the passage of military and humanitarian logistics through its borders. (Isaias later split from the ELF, which has since formed a series of splinter groups). At the time, Sudan’s involvement was crucial to their success, but it would be difficult for Sudan to resort to the same tactics again.

If Khartoum does so, it has much to lose. Abiy could retaliate by supporting Sudanese rebel groups following unstable peace accords they signed with Sudan’s transitional government in October—for example, in Sudan’s Blue Nile state, which borders Ethiopia’s Benishangul-Gumuz state, the site of the GERD. Isaias could also support subgroups of the Beja —a group of tribes living between the Red Sea and the Nile—in a tactical alliance with him against the Beni Amer ethnic group in eastern Sudan and Eritrea traditionally aligned with the ELF, as well as seek to enlist discontented Sudanese opposition figures who were previously based in Eritrea from the mid-1990s to 2006. Since the fall of Bashir, tensions have erupted in eastern Sudan—including in Kassala, Gadaref, and Port Sudan —between groups aligned with Eritrea’s government and those opposed to it.

Meanwhile, Eritrea is getting involved; it is hosting the ENDF on its territory although it remains unclear if Eritrea’s own forces are involved in fighting. On Tigray state television, Tigray’s regional president Debretsion Gebremichael said forces aligned with Isaias bombed Humera—a strategic Tigrayan town on the triple frontier between Ethiopia, Eritrea, and Sudan on Nov. 9 with heavy artillery, that Eritrean and Tigrayan forces are fighting on the border, and that ENDF forces have otherwise been restricted in their movements. While Abiy’s government earlier claimed it had captured territory from Humera to Shire, about 160 miles east in Tigray, it quickly retracted that claim.

Despite initial successes, the TPLF may not have the backing of Sudan to keep going, especially if Abiy and Isaias can make compromises to enlist Sudan’s support. Although everyone from Sudan’s Hamdok and the African Union to Pope Francis and the U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee is calling for a cease-fire and negotiations, Abiy will only call for talks if the ENDF and other security forces continue to fragment to a point of no return and fail on the battlefield. Without Sudan, it seems that the TPLF’s only remaining hope would be to overthrow Abiy’s government or seek to assassinate him with the support of his many other enemies.

Both Sudan and Egypt remain at odds with Ethiopia on the filling and operations of the GERD, which could eventually upend preexisting allocations of water resources to Egypt and Sudan. For now, Sudan is continuing to exploit its leverage in the Tigray conflict and the dam negotiations to secure official demarcation from Abiy of the Fashqa triangle—a formal transfer of a significant amount of territory to Sudan. Since the civil war began, Sudan’s transitional Sovereign Council has already announced that it will not compromise “on any inch of Sudanese territory” with Ethiopia, according to the Sudan News Agency.

Sudan could always use its official border closures as a pretext to supply the TPLF and deny the ENDF and forces loyal to Abiy the ability to attack the TPLF from Sudanese territory. Both Kassala and Gadaref states are awash with contraband weapons smuggling, which Sudan’s military could fully shut down—but only if it chooses to do so. If Ethiopia grants Sudan the concessions it wants when it comes to sharing the waters of the Nile and returning the Fashqa triangle, Khartoum could tip the balance.

Officials privy to private talks between Abiy and Sudanese officials earlier this year told us Sudan sought during the GERD talks to seek implementation of the 1902 border demarcation treaty; by that agreement, Sudan continues to seek full control over Fashqa. These sources told us that Sudanese officials were perturbed by Abiy’s pusillanimous approach on the issue and subsequent exchanges of gunfire between Ethiopian and Sudanese soldiers on their border following Sudanese protests that armed Amhara farmers were making further incursions.

If Sudan makes the formal transfer of Fashqa an explicit condition for refusing logistical support to the TPLF, that could prove fatal for Abiy, but it would be a risky move; several changes in regime over the last century in both countries pushed Fashqa to the back-burner and Bashir tolerated its unresolved status thanks to good relations with Ethiopia’s former TPLF-led government.

If Sudan makes the formal transfer of Fashqa an explicit condition for refusing logistical support to the TPLF, that could prove fatal for Abiy

If Abiy were to concede, he would lose the expansive support he imagines he has among ethnic Amhara. Much like so-called ancestral lands removed from Amhara and attached by the TPLF to Tigray in the 1990s, Fashqa is an issue for which Amhara will lay down their lives; and if Abiy refuses, Sudan could respond by supporting the TPLF.

Since last week, scores of ill-equipped Amhara irregular forces along the Amhara-Tigray border have died fighting seeking to reclaim these ancestral lands, according to the senior Ethiopian diplomat. He said such unpublicized failures have both triggered Abiy’s reshuffle of the Amhara regional president (an Abiy loyalist who is now director-general of the National Intelligence and Security Service) and could deepen discontent there, leading to another Amhara insurrection to install hard-line regional leaders which could be more serious than an internal convulsion last year.

It is evident from Abiy’s latest reshuffling of his military, intelligence, security, and foreign-policy establishment that he depends increasingly on a small network of Amhara ostensible loyalists—and they could ultimately turn on him and take power for themselves if he does not continue to serve their interests against the TPLF and their designs to restructure the Ethiopian state in their image.

If the TPLF is able to drain personnel away from a war it is already fighting on three fronts—Amhara, Afar, and Eritrea—and invade Eritrea and bring regime change there, that could give it access to additional territory as well as logistics through the Red Sea. Tigray already hosts several Eritrean opposition groups as well as small military bases for them, but it’s a tall order.

The TPLF would face the challenge of defeating both the Eritrean Defense Forces and the ENDF in Eritrea, which hosts a naval and air base for the United Arab Emirates, with whom Abiy has built close relations. On Nov. 6, the Emirati foreign minister Sheikh Abdullah bin Zayed Al Nahyan noted the UAE’s “solidarity” with “friendly countries in their war against” terrorism—suggesting alignment with Abiy and Isaias against the TPLF. Abu Dhabi could use its significant clout with Burhan and other key figures in Sudan’s unstable government to achieve its objectives.

In Sudan, a retired senior officer who was a member of the ELF told us that Isaias has been drafting additional military conscripts since October in different parts of Eritrea. He said some Eritrean soldiers—principally from the Beni Amer and related tribes—have refused to fight and defected into Kassala state in Sudan. This may indicate the unreadiness of at least some groups in the Eritrean Defense Forces to fight. In Kassala, Beni Amer—who are also present in Eritrea—are being roiled up to fight against Isaias’s regime.

Both the TPLF and Isaias see Kassala as their strategic backyard. The TPLF built relations with anti-Isaias groups among the Beni Amer in Kassala after the 1998-2000 Eritrean-Ethiopian war, and Isaias knows that any challenge for control of western Eritrea can come from Beni Amer allied with the ELF.

But an overthrow of Isaias in Eritrea could only realistically happen if Sudan’s military provides support to Eritrean opposition groups in Sudan, and only if the TPLF simultaneously advances into Eritrea—also with tacit Sudanese support.

As the war intensifies, Abiy seems to be reading from the same script as his TPLF predecessors even as he seeks to depose them.

Although the previous governor in Kassala was a Beni Amer closely aligned with the TPLF as well as the Bashir regime’s army, Isaias may have already tilted the balance against the TPLF there. After Sudan removed military governors as part of the new regime’s reforms, another Beni Amer, Saleh Ammar, was proposed as governor, but his appointment was abandoned following protests led by Beja subtribes linked to Isaias.

Meanwhile, in Ethiopia, Tigrayan officers are being disarmed and Tigrayans across government structures are being targeted; in the federal police, serving officers told us, Tigrayans have been asked to take leave; and even in the African Union Mission in Somalia, which fights al-Shabab, two senior officers said that more than 200 Tigrayan officers have had their guns confiscated.

As the war intensifies, Abiy seems to be reading from the same script as his TPLF predecessors even as he seeks to depose them—organizing state sponsored support rallies for the war, jailing journalists, and labelling myriad opponents lashing out against his hypocrisy as terrorists.

There is more at stake in Ethiopia’s civil war than a Tigrayan rebellion. At worst, officers throughout Ethiopia’s ethnically based military will join a chaotic rebellion, and the military will find itself increasingly enmeshed in an already cataclysmic web of interethnic fighting across Ethiopia and at its borders—a regional catastrophe that will ensnare both Eritrea and Sudan, and possibly more actors.

War is already underway on the Eritrean front, with Ethiopian military commanders appearing on the Tigray-Eritrea border. And if the Ethiopian army fails to choke off the TPLF from the small slice of land between Tigray and Sudan—Abiy’s chief of staff claims it has, but senior sources say the battle there is still unresolved—Sudan will determine the outcome of Ethiopia’s civil war.

Despite initial successes, the TPLF may not have the backing of Sudan to keep going, especially if Abiy and Isaias can make compromises to enlist Sudan’s support. Although everyone from Sudan’s Hamdok and the African Union to Pope Francis and the U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee is calling for a cease-fire and negotiations, Abiy will only call for talks if the ENDF and other security forces continue to fragment to a point of no return and fail on the battlefield. Without Sudan, it seems that the TPLF’s only remaining hope would be to overthrow Abiy’s government or seek to assassinate him with the support of his many other enemies.

Both Sudan and Egypt remain at odds with Ethiopia on the filling and operations of the GERD, which could eventually upend preexisting allocations of water resources to Egypt and Sudan. For now, Sudan is continuing to exploit its leverage in the Tigray conflict and the dam negotiations to secure official demarcation from Abiy of the Fashqa triangle—a formal transfer of a significant amount of territory to Sudan. Since the civil war began, Sudan’s transitional Sovereign Council has already announced that it will not compromise “on any inch of Sudanese territory” with Ethiopia, according to the Sudan News Agency.

Sudan could always use its official border closures as a pretext to supply the TPLF and deny the ENDF and forces loyal to Abiy the ability to attack the TPLF from Sudanese territory. Both Kassala and Gadaref states are awash with contraband weapons smuggling, which Sudan’s military could fully shut down—but only if it chooses to do so. If Ethiopia grants Sudan the concessions it wants when it comes to sharing the waters of the Nile and returning the Fashqa triangle, Khartoum could tip the balance.

Officials privy to private talks between Abiy and Sudanese officials earlier this year told us Sudan sought during the GERD talks to seek implementation of the 1902 border demarcation treaty; by that agreement, Sudan continues to seek full control over Fashqa. These sources told us that Sudanese officials were perturbed by Abiy’s pusillanimous approach on the issue and subsequent exchanges of gunfire between Ethiopian and Sudanese soldiers on their border following Sudanese protests that armed Amhara farmers were making further incursions.

If Sudan makes the formal transfer of Fashqa an explicit condition for refusing logistical support to the TPLF, that could prove fatal for Abiy, but it would be a risky move; several changes in regime over the last century in both countries pushed Fashqa to the back-burner and Bashir tolerated its unresolved status thanks to good relations with Ethiopia’s former TPLF-led government.

If Sudan makes the formal transfer of Fashqa an explicit condition for refusing logistical support to the TPLF, that could prove fatal for Abiy

If Abiy were to concede, he would lose the expansive support he imagines he has among ethnic Amhara. Much like so-called ancestral lands removed from Amhara and attached by the TPLF to Tigray in the 1990s, Fashqa is an issue for which Amhara will lay down their lives; and if Abiy refuses, Sudan could respond by supporting the TPLF.

Since last week, scores of ill-equipped Amhara irregular forces along the Amhara-Tigray border have died fighting seeking to reclaim these ancestral lands, according to the senior Ethiopian diplomat. He said such unpublicized failures have both triggered Abiy’s reshuffle of the Amhara regional president (an Abiy loyalist who is now director-general of the National Intelligence and Security Service) and could deepen discontent there, leading to another Amhara insurrection to install hard-line regional leaders which could be more serious than an internal convulsion last year.

It is evident from Abiy’s latest reshuffling of his military, intelligence, security, and foreign-policy establishment that he depends increasingly on a small network of Amhara ostensible loyalists—and they could ultimately turn on him and take power for themselves if he does not continue to serve their interests against the TPLF and their designs to restructure the Ethiopian state in their image.

If the TPLF is able to drain personnel away from a war it is already fighting on three fronts—Amhara, Afar, and Eritrea—and invade Eritrea and bring regime change there, that could give it access to additional territory as well as logistics through the Red Sea. Tigray already hosts several Eritrean opposition groups as well as small military bases for them, but it’s a tall order.

The TPLF would face the challenge of defeating both the Eritrean Defense Forces and the ENDF in Eritrea, which hosts a naval and air base for the United Arab Emirates, with whom Abiy has built close relations. On Nov. 6, the Emirati foreign minister Sheikh Abdullah bin Zayed Al Nahyan noted the UAE’s “solidarity” with “friendly countries in their war against” terrorism—suggesting alignment with Abiy and Isaias against the TPLF. Abu Dhabi could use its significant clout with Burhan and other key figures in Sudan’s unstable government to achieve its objectives.

In Sudan, a retired senior officer who was a member of the ELF told us that Isaias has been drafting additional military conscripts since October in different parts of Eritrea. He said some Eritrean soldiers—principally from the Beni Amer and related tribes—have refused to fight and defected into Kassala state in Sudan. This may indicate the unreadiness of at least some groups in the Eritrean Defense Forces to fight. In Kassala, Beni Amer—who are also present in Eritrea—are being roiled up to fight against Isaias’s regime.

Both the TPLF and Isaias see Kassala as their strategic backyard. The TPLF built relations with anti-Isaias groups among the Beni Amer in Kassala after the 1998-2000 Eritrean-Ethiopian war, and Isaias knows that any challenge for control of western Eritrea can come from Beni Amer allied with the ELF.

But an overthrow of Isaias in Eritrea could only realistically happen if Sudan’s military provides support to Eritrean opposition groups in Sudan, and only if the TPLF simultaneously advances into Eritrea—also with tacit Sudanese support.

As the war intensifies, Abiy seems to be reading from the same script as his TPLF predecessors even as he seeks to depose them.

Although the previous governor in Kassala was a Beni Amer closely aligned with the TPLF as well as the Bashir regime’s army, Isaias may have already tilted the balance against the TPLF there. After Sudan removed military governors as part of the new regime’s reforms, another Beni Amer, Saleh Ammar, was proposed as governor, but his appointment was abandoned following protests led by Beja subtribes linked to Isaias.

Meanwhile, in Ethiopia, Tigrayan officers are being disarmed and Tigrayans across government structures are being targeted; in the federal police, serving officers told us, Tigrayans have been asked to take leave; and even in the African Union Mission in Somalia, which fights al-Shabab, two senior officers said that more than 200 Tigrayan officers have had their guns confiscated.

As the war intensifies, Abiy seems to be reading from the same script as his TPLF predecessors even as he seeks to depose them—organizing state sponsored support rallies for the war, jailing journalists, and labelling myriad opponents lashing out against his hypocrisy as terrorists.

There is more at stake in Ethiopia’s civil war than a Tigrayan rebellion. At worst, officers throughout Ethiopia’s ethnically based military will join a chaotic rebellion, and the military will find itself increasingly enmeshed in an already cataclysmic web of interethnic fighting across Ethiopia and at its borders—a regional catastrophe that will ensnare both Eritrea and Sudan, and possibly more actors.

War is already underway on the Eritrean front, with Ethiopian military commanders appearing on the Tigray-Eritrea border. And if the Ethiopian army fails to choke off the TPLF from the small slice of land between Tigray and Sudan—Abiy’s chief of staff claims it has, but senior sources say the battle there is still unresolved—Sudan will determine the outcome of Ethiopia’s civil war.

Thanks but I managed to read the article soon after I made that postMeanwhile, Eritrea is getting involved; it is hosting the ENDF on its territory although it remains unclear if Eritrea’s own forces are involved in fighting. On Tigray state television, Tigray’s regional president Debretsion Gebremichael said forces aligned with Isaias bombed Humera—a strategic Tigrayan town on the triple frontier between Ethiopia, Eritrea, and Sudan on Nov. 9 with heavy artillery, that Eritrean and Tigrayan forces are fighting on the border, and that ENDF forces have otherwise been restricted in their movements. While Abiy’s government earlier claimed it had captured territory from Humera to Shire, about 160 miles east in Tigray, it quickly retracted that claim.

Despite initial successes, the TPLF may not have the backing of Sudan to keep going, especially if Abiy and Isaias can make compromises to enlist Sudan’s support. Although everyone from Sudan’s Hamdok and the African Union to Pope Francis and the U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee is calling for a cease-fire and negotiations, Abiy will only call for talks if the ENDF and other security forces continue to fragment to a point of no return and fail on the battlefield. Without Sudan, it seems that the TPLF’s only remaining hope would be to overthrow Abiy’s government or seek to assassinate him with the support of his many other enemies.

Both Sudan and Egypt remain at odds with Ethiopia on the filling and operations of the GERD, which could eventually upend preexisting allocations of water resources to Egypt and Sudan. For now, Sudan is continuing to exploit its leverage in the Tigray conflict and the dam negotiations to secure official demarcation from Abiy of the Fashqa triangle—a formal transfer of a significant amount of territory to Sudan. Since the civil war began, Sudan’s transitional Sovereign Council has already announced that it will not compromise “on any inch of Sudanese territory” with Ethiopia, according to the Sudan News Agency.

Sudan could always use its official border closures as a pretext to supply the TPLF and deny the ENDF and forces loyal to Abiy the ability to attack the TPLF from Sudanese territory. Both Kassala and Gadaref states are awash with contraband weapons smuggling, which Sudan’s military could fully shut down—but only if it chooses to do so. If Ethiopia grants Sudan the concessions it wants when it comes to sharing the waters of the Nile and returning the Fashqa triangle, Khartoum could tip the balance.

Officials privy to private talks between Abiy and Sudanese officials earlier this year told us Sudan sought during the GERD talks to seek implementation of the 1902 border demarcation treaty; by that agreement, Sudan continues to seek full control over Fashqa. These sources told us that Sudanese officials were perturbed by Abiy’s pusillanimous approach on the issue and subsequent exchanges of gunfire between Ethiopian and Sudanese soldiers on their border following Sudanese protests that armed Amhara farmers were making further incursions.

If Sudan makes the formal transfer of Fashqa an explicit condition for refusing logistical support to the TPLF, that could prove fatal for Abiy, but it would be a risky move; several changes in regime over the last century in both countries pushed Fashqa to the back-burner and Bashir tolerated its unresolved status thanks to good relations with Ethiopia’s former TPLF-led government.

If Sudan makes the formal transfer of Fashqa an explicit condition for refusing logistical support to the TPLF, that could prove fatal for Abiy

If Abiy were to concede, he would lose the expansive support he imagines he has among ethnic Amhara. Much like so-called ancestral lands removed from Amhara and attached by the TPLF to Tigray in the 1990s, Fashqa is an issue for which Amhara will lay down their lives; and if Abiy refuses, Sudan could respond by supporting the TPLF.

Since last week, scores of ill-equipped Amhara irregular forces along the Amhara-Tigray border have died fighting seeking to reclaim these ancestral lands, according to the senior Ethiopian diplomat. He said such unpublicized failures have both triggered Abiy’s reshuffle of the Amhara regional president (an Abiy loyalist who is now director-general of the National Intelligence and Security Service) and could deepen discontent there, leading to another Amhara insurrection to install hard-line regional leaders which could be more serious than an internal convulsion last year.

It is evident from Abiy’s latest reshuffling of his military, intelligence, security, and foreign-policy establishment that he depends increasingly on a small network of Amhara ostensible loyalists—and they could ultimately turn on him and take power for themselves if he does not continue to serve their interests against the TPLF and their designs to restructure the Ethiopian state in their image.

If the TPLF is able to drain personnel away from a war it is already fighting on three fronts—Amhara, Afar, and Eritrea—and invade Eritrea and bring regime change there, that could give it access to additional territory as well as logistics through the Red Sea. Tigray already hosts several Eritrean opposition groups as well as small military bases for them, but it’s a tall order.

The TPLF would face the challenge of defeating both the Eritrean Defense Forces and the ENDF in Eritrea, which hosts a naval and air base for the United Arab Emirates, with whom Abiy has built close relations. On Nov. 6, the Emirati foreign minister Sheikh Abdullah bin Zayed Al Nahyan noted the UAE’s “solidarity” with “friendly countries in their war against” terrorism—suggesting alignment with Abiy and Isaias against the TPLF. Abu Dhabi could use its significant clout with Burhan and other key figures in Sudan’s unstable government to achieve its objectives.

In Sudan, a retired senior officer who was a member of the ELF told us that Isaias has been drafting additional military conscripts since October in different parts of Eritrea. He said some Eritrean soldiers—principally from the Beni Amer and related tribes—have refused to fight and defected into Kassala state in Sudan. This may indicate the unreadiness of at least some groups in the Eritrean Defense Forces to fight. In Kassala, Beni Amer—who are also present in Eritrea—are being roiled up to fight against Isaias’s regime.

Both the TPLF and Isaias see Kassala as their strategic backyard. The TPLF built relations with anti-Isaias groups among the Beni Amer in Kassala after the 1998-2000 Eritrean-Ethiopian war, and Isaias knows that any challenge for control of western Eritrea can come from Beni Amer allied with the ELF.

But an overthrow of Isaias in Eritrea could only realistically happen if Sudan’s military provides support to Eritrean opposition groups in Sudan, and only if the TPLF simultaneously advances into Eritrea—also with tacit Sudanese support.

As the war intensifies, Abiy seems to be reading from the same script as his TPLF predecessors even as he seeks to depose them.

Although the previous governor in Kassala was a Beni Amer closely aligned with the TPLF as well as the Bashir regime’s army, Isaias may have already tilted the balance against the TPLF there. After Sudan removed military governors as part of the new regime’s reforms, another Beni Amer, Saleh Ammar, was proposed as governor, but his appointment was abandoned following protests led by Beja subtribes linked to Isaias.

Meanwhile, in Ethiopia, Tigrayan officers are being disarmed and Tigrayans across government structures are being targeted; in the federal police, serving officers told us, Tigrayans have been asked to take leave; and even in the African Union Mission in Somalia, which fights al-Shabab, two senior officers said that more than 200 Tigrayan officers have had their guns confiscated.

As the war intensifies, Abiy seems to be reading from the same script as his TPLF predecessors even as he seeks to depose them—organizing state sponsored support rallies for the war, jailing journalists, and labelling myriad opponents lashing out against his hypocrisy as terrorists.

There is more at stake in Ethiopia’s civil war than a Tigrayan rebellion. At worst, officers throughout Ethiopia’s ethnically based military will join a chaotic rebellion, and the military will find itself increasingly enmeshed in an already cataclysmic web of interethnic fighting across Ethiopia and at its borders—a regional catastrophe that will ensnare both Eritrea and Sudan, and possibly more actors.

War is already underway on the Eritrean front, with Ethiopian military commanders appearing on the Tigray-Eritrea border. And if the Ethiopian army fails to choke off the TPLF from the small slice of land between Tigray and Sudan—Abiy’s chief of staff claims it has, but senior sources say the battle there is still unresolved—Sudan will determine the outcome of Ethiopia’s civil war.

I wouldn’t mind us squaring up with Sudan in honor of Yohannes IV, a real Tigrayan hero and leader.....

thatrapsfan

Superstar

Where there’s smoke there’s fire, I got no trust for Egypt...

Very interesting. Eritrea is banking on the GERD being a success. So not sure what to make of it. Maybe they’re trying to convince them that the TPLF’s days are numbered and they need to stop trying to support them and other insurgents/secessionists in Ethiopia.

Hell nah

Although an internal coup within PFDJ would probably be the ideal scenario for regime change in Eritrea without the possibility of major escalation of violence. We need new leadership with as smooth transition as possible

loyola llothta

☭☭☭

loyola llothta

☭☭☭

Disinformation in Tigray: Manufacturing Consent For a Secessionist War

New African Institute

19 May 2021

Disinformation in Tigray: Manufacturing Consent For a Secessionist War

Click HERE to scroll down and read the report, or download it.

New African Institute

19 May 2021

Disinformation in Tigray: Manufacturing Consent For a Secessionist War

Corporate media in the imperial countries have spread disinformation on the real nature of the fighting in Ethiopia’s Tigray state.

“Eritrea has served as the primary scapegoat.”

Today, New Africa Institute publishes its Disinformation in Tigray report to provide an evidence-based analysis of the conflict in Ethiopia’s Tigray Regional State, which is an irredentist, ethnic secessionist war led by the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) against the multiethnic federal government. Although the conflict officially started on November 4, 2020 after TPLF, by its own admission, attacked the federal government’s Northern Command based in Tigray, this showdown had been brewing for decades.

Since the start of hostilities, there has been an explosion of disinformation in the mainstream and social media. This report carefully analyzes the causes and methods of disinformation propagation. Ultimately, the disinformation serves to manufacture consent for an unpopular irredentist, ethnic secessionist war that could not be justified in the eyes of the international public through honest reporting.

The media, non-governmental organizations and Western governments have forwarded a number of allegations of crimes upon the people of Tigray perpetrated by the Ethiopian and Eritrean militaries. Eritrea has served as the primary scapegoat. Much of the reporting of these crimes, devoid of evidence and context, has proven sensational and racist with savage-like portrayals of Eritreans and Ethiopians that draw on old colonial tropes of Africans. This report looks beyond the gaudy headlines and provides sober, evidence-based analysis of the major allegations. Significant focus is given to social media as most disinformation about Tigray originates there.

Additionally, this report assesses the nature of and problems with Western media’s overall coverage of the Tigray conflict. Lastly, it provides analysis of the actions by Western governments and likely consequences of those actions to encourage better policy decisions in the Horn of Africa moving forward.

Click HERE to scroll down and read the report, or download it.