Germany and Namibia: What's the right price to pay for genocide?

By Tim Whewell

BBC News, Namibia

March 31, 2021 | 23:19:05

A deal that could set a precedent for former colonies all around the world is being thrashed out between Germany and Namibia, to heal the wounds of what's now widely regarded as a genocide by colonial forces. But how do you make up for destroying an entire society? In Namibia, descendants of both victims and colonisers are arguing fiercely about the talks.

"Along this whole beach, there was a concentration camp," says Laidlaw Peringanda. "The barbed wire ran where you see the car park today."

The artist and social activist is pointing past a row of open-air cafes and a children's playground on the promenade in Swakopmund, Namibia's main seaside resort, where the cold breakers of the Atlantic crash against the edge of the Namib Desert.

"My great-grandmother told me some of our family were brought here and forced to work, and they died."

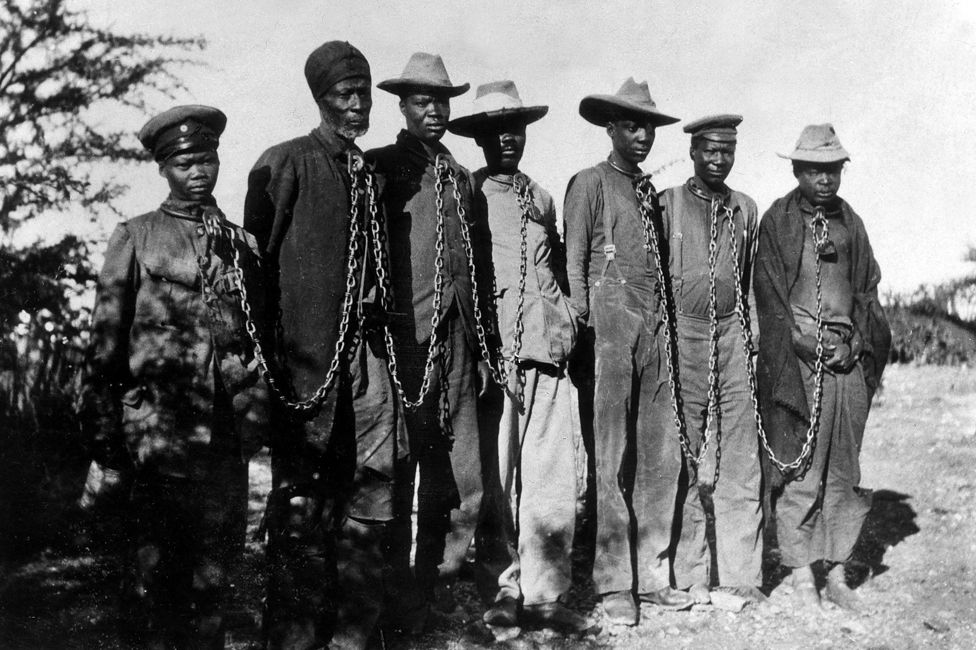

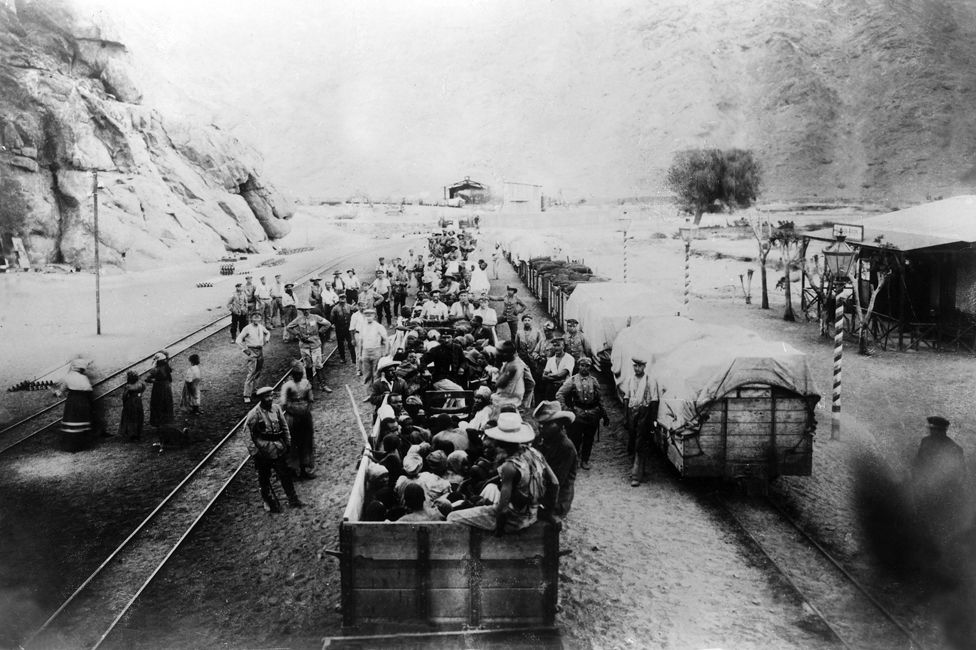

He's talking about the years 1904-1908, when present-day Namibia was the German colony of South West Africa. Tens of thousands died as colonial forces brutally suppressed uprisings by two of the main peoples of the country, the Herero and Nama, killing many and driving others into a desert (the Omaheke Desert in the east of the country) where many starved to death. Survivors ended up in camps where they were used as slave labour, dying of cold, malnutrition, exhaustion and violence. As many as 65,000 of the 80,000 Herero living in German South West Africa at the start of colonial rule are estimated to have perished, as well as perhaps 10,000 of an estimated 20,000 Nama.

Since 2015, when Germany formally acknowledged that the atrocities constituted genocide, it has been negotiating a restorative justice deal with Namibia that will set a global precedent. Never before has a former colonial power sat down with a former colony in this way to work out a comprehensive agreement about the legacy of the past.

Germany has said it will make a formal apology - though the wording is still to be worked out. But the bigger question for Namibians is what form any material compensation will take.

Laidlaw Peringanda at a mass grave of concentration camp victims

Laidlaw Peringanda, like most Hereros, is in no doubt about what he wants from the talks - a massive financial deal that will help restore his people to the prosperity he believes they enjoyed, as cattle-herders, before the genocide. Afterwards, most of their land was split into private farms for German settlers. And today most Herero and Nama live either on small overcrowded areas of communal land that were later allocated to them, or in towns - many in the "informal settlements" or shanty towns that house 40% of Namibia's people.

In Swakopmund, there's a massive social gulf between the pretty, colonial-era town centre with its pastel-painted gabled buildings - home still to many grandchildren and great-grandchildren of the original colonists - and the shacks cobbled together from planks and metal sheeting that extend for miles to the north.

"They don't have flushing toilets, they don't have drinkable water, there's no electricity," Laidlaw says.

"Some of the people living there, they are descendants of the victims of the concentration camps. It's really unfair what is happening.

"Germany must buy back our ancestral land."

That's a demand you hear over and over again.

The hope is that the German government will fund a land reform programme to enable farms to be bought from German Namibian farmers, and distributed to Herero and Nama.

German Namibians are believed to be the biggest group among the white farmers who own about 70% of the country's farmland, and some of their holdings are vast - one covers 400 sq miles.

How realistic is this? Namibia's chief negotiator, Dr Zed Ngavirue, says Germany has "acknowledged they need to do something to help us reconstruct our society" and agreed to provide some money - as part of a wider agreement - to buy up land from willing sellers.

Zed Ngavirue, chief negotiator

But he adds: "I couldn't try and fool myself that the land issue will be solved by Germany. It's not loss of land as a result of German colonisation only."

Many more white settlers arrived after Germany lost its colony in World War One, and South West Africa came to be ruled by South Africa for 70 years. And since independence in 1990 land has been bought both by black Namibians and by foreigners.

The German government refuses to use the word "reparations" but Zed Ngavirue says other practical projects being discussed include possible German help with health, education, housing and water desalination. He says the talks are too delicate to name any sums yet.

As for the German side, it declines to say anything publicly about the progress of the talks.

After six years without a result, Laidlaw is one of many Herero and Nama growing increasingly impatient.

He argues that Germany should be talking not just to the Namibian government, but also directly to Herero and Nama leaders, such as Herero paramount chief Vekuii Rukoro, who has attempted to sue Germany for compensation in the US courts, so far without success. The fear is that any benefits from a government-to-government deal may go partly to communities that never suffered in the genocide, such as the Ovambo, now Namibia's largest ethnic group.

Vekuii Rukoro

Chief Rukoro's adviser Festus Mundjuua says the government wants "to put their hands on the cash because they have their own projects for which they have no money". That's denied by the government, which says any funds will be managed by affected communities.

But it's not just victims' descendants who are sceptical about the talks. So too are some of Namibia's remaining 30,000 or so German speakers, descendants of the colonists.

"The genocide myth is nothing more than moral blackmail," says historian Dr Andreas Vogt. Like many German-Namibians, he argues that the infamous "extermination order" signed by the commander of the colonial forces, Gen Lothar von Trotha, in 1904, saying that "any Herero found inside the German frontier, with or without a gun or cattle, will be executed", was not state policy and was never implemented.

"The portrayal of - on the one side - a genocidal, brutal and unforgiving German colonial authority, and on the other, the pristine and completely innocent Herero people is tainted. It takes two parties to tango," Vogt says.

He and many other German Namibians point out that the Herero rebelled against German rule in 1904 - killing about 120 German settlers - but were then defeated at the decisive Battle of Waterberg.

Last year a German-Namibian who served as a government minister shortly after independence, Anton von Wietersheim, helped launch an initiative to encourage German-speaking Namibians to discuss the past, both among themselves and together with Herero and Nama representatives, though plans for a conference of German-Namibians have been delayed because of Covid-19.

"The realisation has still to come to many of our white compatriots about what situation these affected people are actually in as a result of the historic happenings," he says.

Von Wietersheim believes that if German-Namibians back the genocide talks it will encourage Germany to reach a deal, which Namibia is keen to conclude before German elections in September.

Herero prisoners in chains (1904)

German-Namibian academic and activist Henning Melber, who has studied the background to the talks, believes other former colonial powers in Europe have privately expressed concerns to Germany that an agreement with Namibia might set off an avalanche of claims against various colonisers by nations in Africa, south-east Asia and elsewhere.

Tanzania, the successor to another former German colony, Tanganyika, is already demanding reparations for atrocities, and potentially other former colonies could follow suit.

But Melber says: "I think Germany would be flexible about the amount it could offer, if it had some guarantee that (the deal) would close the chapter once and for all. The issue is to avoid a precedent with wide implications."

A train with prisoners leaving for the concentration camp

For his part, Zed Ngavirue, a veteran diplomat, avoids any promises about what can be achieved.

"Politics is the art of the possible," he says with a smile.

But in the squalid slums outside Swakopmund, where some Herero work today on minimum wages for the descendants of Germans who used their great-grandparents as slaves, there's not the same understanding.

"Young people, some of them are fed up, they want to take the land by force," Laidlaw Peringanda says. "So maybe the German government should not play hide and seek with us."

Germany and Namibia: What's the right price to pay for genocide?